By Valeria Kolodezhna

Translated by Jennifer Castner

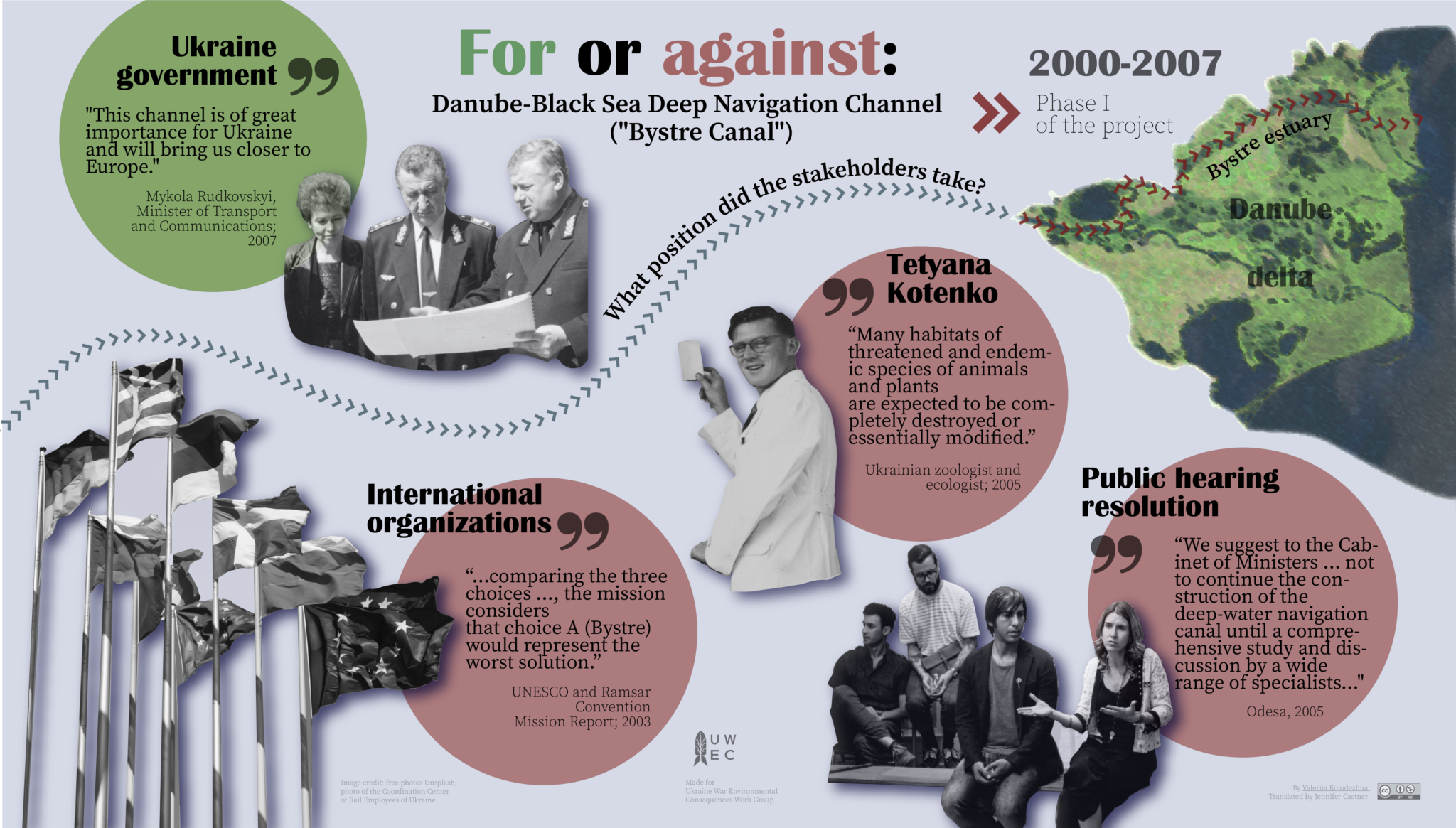

In order to avoid a global food crisis, Ukraine is forced to seek new pathways to export grain. The Danube, one of Europe’s largest rivers, is becoming increasingly important in resolving this issue. Construction of a navigable canal began there in the early 2000, and now a second phase of construction is on the agenda. At the outset, the project had many contradictions; is it reasonable to resume work now? UWEC experts analyze the new plans from an environmental perspective.

Thanks to Russia’s blocking of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, the attractiveness of using the Danube River (one of Europe’s largest rivers) for navigation has increased for Ukraine and many other countries. In the past, transport infrastructure development on the Danube has always been complex and attracted polarized opinions. The idea of any construction in the river delta was perceived especially ambiguously beginning in 1998, when the Danube Reserve acquired the status of a biosphere reserve and was included in the UNESCO “Man and the Biosphere” program.

Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that Ukraine is preparing to resume work on both the Deep-water Navigation Channel (DNC) in the Danube Delta and port infrastructure.

The first attempt to build the DNC took place in the early 2000s. Despite opposition by scientists and community activists from 90 countries, the first stage of the project was completed inside the boundaries of the UNESCO reserve. The illusion of an economic miracle – in the form of the channel’s anticipated income – dissolved rapidly, but the environmentalists’ warnings came to pass. Will a second attempt succeed with a win-win strategy?

The Danube Delta’s value

The Danube Delta is a center of biodiversity on a global scale, the second largest delta in Europe, and the best preserved European delta. It is located on the border of Ukraine and Romania, contains 3,446 km2 of freshwater swamps, lakes, ponds, and canals previously artificially created, and is a refuge for a large number of birds, fish, and amphibians.

It is the largest remaining natural wetland in Europe. Only 9% of the land area is permanently under water. More than 1,200 plant species, 300 bird species, and 45 freshwater fish are found in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve in its Ukrainian and Romanian parts.

Although in Ukraine the Danube Biosphere Reserve occupies just 20% of the delta area, 205 species of animals subject to special protection under the Bern Convention, including 42 bird species have been documented on its territory. Responsibility for the protection and conservation of this biodiversity “Klondike” lies primarily on the shoulders of Ukraine and Romania.

Biosphere reserve vs. navigable waterway – protecting nature or ensuring economic gain?

The Danube Biosphere Reserve was created in 1998. Prior to that, the reserve existed as a branch of the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve. Its creation was financed at that time by the World Bank, with whom Ukraine’s government signed an agreement for the “Conservation of biological diversity in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta” (1995-1998).

International recognition arrived at the same time: Ukraine’s reserve was presented as one of the most successful environmental projects at the World Exhibition in Hannover in 2000.

But in that same year, Ukraine began planning the construction of a deep navigation channel (DNC) on the Danube. Officially named the Danube-Black Sea Deep-sea Navigation Channel, it was more colloquially known as the “Kirpa Canal” in honor of the Ukraine Minister of Transport who initiated the project.

Heorhii Kirpa argued that, without its own shipping route, Ukraine was losing 60 million US dollars each year, and along with that income, potential jobs were being lost as well.

The solution lay on the surface. A shipping route is needed to kill two birds with one stone: boost the economy and bring Ukraine closer to Europe. The authorities at the time readily supported the minister’s idea. So much so that they were not averse to turning a blind eye to a very important fact: construction would need to take place at the mouth of Bystroye, a middle distributary of the Danube, within the newly formed biosphere reserve.

Construction on the territory of nature reserves not related to their activities is prohibited by law in Ukraine. But in 2004, Ukraine’s president issued a special decree completely reversing the situation. According to the decree, roughly 1,000 hectares within the protected area were classified as “anthropogenic landscapes,” including the mouth of the Bystroye.

The delta’s protection regime was changed for no obvious reason and without approval by Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences. Accordingly, obstacles to launching the project were eliminated.

Western support for creation of a biosphere reserve clearly indicated that Europe wanted to see the Danube Delta protected, but did Europe need a new shipping route more?

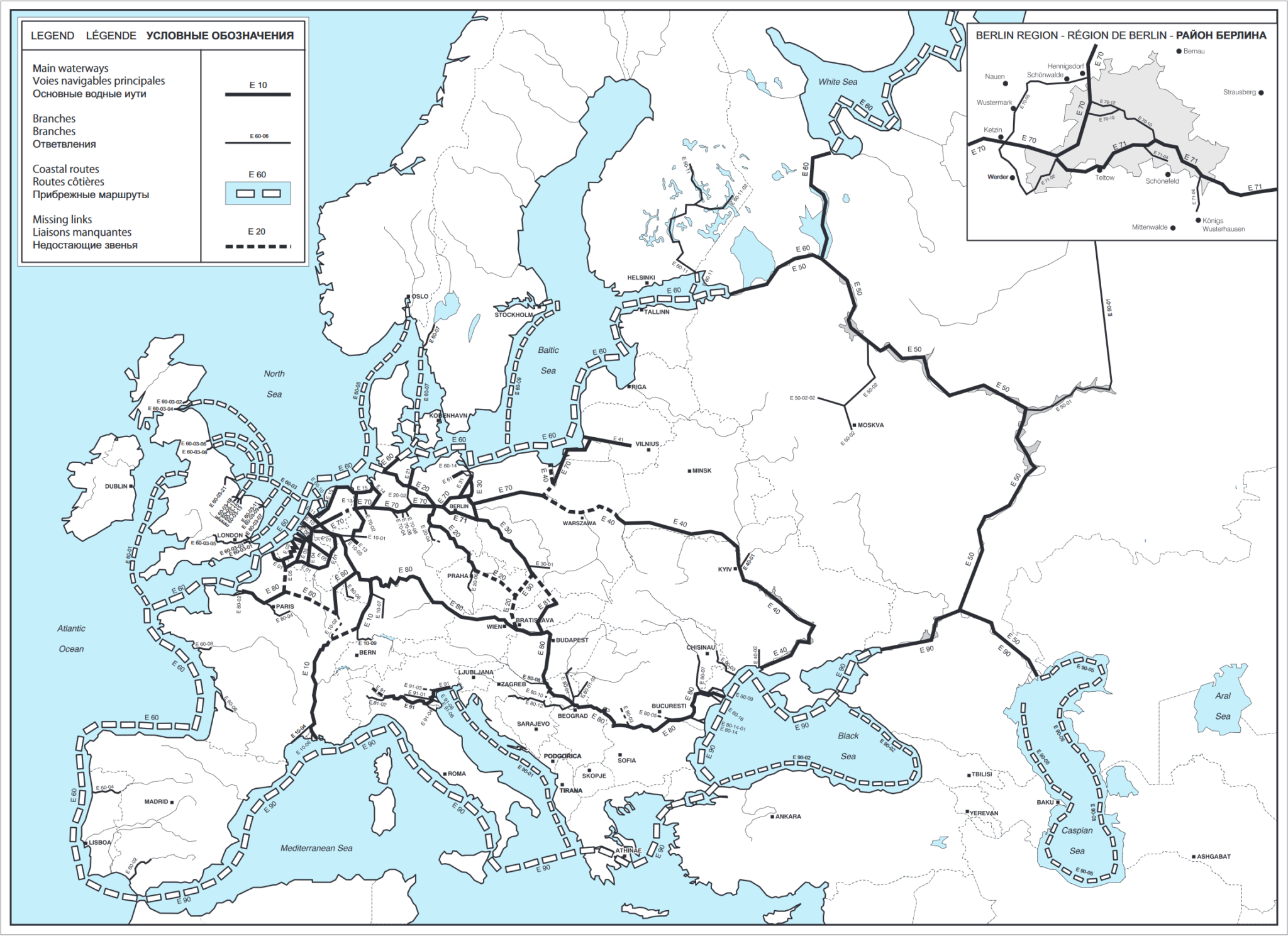

Role of Ukrainian DNC in European river shipping

The role of river navigation, once of great importance in the medieval economy, is gradually declining and is currently less than 6% of total European cargo turnover (not including marine transportation). The cost of rail container transportation has basically caught up with river transport, depriving the latter of its competitive advantages.

Figure 1. Pan-European inland waterway system, master plan. Source: Еuromaidanpress

Figure 2. Cargo shipping dynamics on inland waterways in the European Union. Source: Еurostat

As a result, cargo transportation along the rivers stagnated and decreased in the 21st century. Volumes grew thanks only to “river-sea” connections over short distances in the deltas of large rivers. Thus, the Rhine River basin accounts for 70% of European river traffic. The second largest river system is the Danube, with less than 8% of total shipping traffic.

Figure 3. Rhine and Danube – Europe’s two largest rivers. Source: Market Observation Annual Report-2019

Figures 4-5. While river transport has stagnated as a whole in Europe, it has almost doubled since 2007 on the Danube, apparently due to integration of new basin countries into the European Union. Source: Central Commission for Navigation of the Rhine Market Observation Annual Report-2022

The increase in cargo turnover along the Danube can also be seen in the ports of Ukraine’s main potential competitor – Romania.

But geography is not on Ukraine’s side: for ships heading south from Chernovod, the Chernovoda-Constanta Canal bypasses part of the route along the Danube, reducing the opportunity for transporting goods along the river. Its profitability is also inferior compared to the deep-water passage along the Sulina distributary of the delta in Romania (see an infographic).

However, even this waterway is half the length of the DNC as designed by Ukraine at Bystroye (roughly 70 km and 170 km, respectively). During the war, Romania, Moldova, and France also agreed to improve the Sulina Canal and speed up connection of the Romanian port of Galati to the Ukrainian-Moldovan railway line, reducing the competitiveness of additional shipping lanes.

As you can see, use of a Ukrainian river passage by foreign companies was tantamount to lost time and thus money. It was an unjustified decision to count on foreign cargo flows, but despite this, the Ministry of Transport projected traffic of 76 Ukrainian and 420 foreign ships per day in its plan for the Danube-Black Sea DNC project.

The question of the source of these cargo transportation volumes remains unclear. Of course, the option of transporting Russian cargo remains, but even by 2004 Russian cargo had mostly abandoned Ukrainian ports, to say nothing of the current situation.

Despite these challenges, the Ukrainian government did not abandon the idea of “complete development” of the Danube-Black Sea shipping route (see an infographic). This development assumed dredging the channel up to 7.2 meters deep.

At the same time, active silting of the Bystroye prevents maintaining sufficient depths even in the first phase: vessels with drafts up to 5.85 m. That lags behind the projected draft depths by at least 2 meters (and today, draft depths reach just 3.9 m). It is impossible to compete with the one-way Sulina Canal (the Bystroye Channel was planned with two-way shipping traffic) with such a draft.

Ukraine experienced the insolvency of the Danube-Black Sea DNC especially acutely while shipping grain in July 2022. The liberation of Snake Island made it possible to use the Bystroye route, but its depth allows only empty or half-empty ships to reach ports. Vessels with a large draft (over 1,000 metric tons) must still pass through the Sulina Canal.

In wartime, the delta’s ports were used, among other things, to load ships with Ukrainian grain, work which, in peacetime, can be done much more cheaply in Greater Odesa ports. It was proposed to start the second, final stage of building the Danube DNC precisely against the backdrop of Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian seaports. Indeed, the cost of passage for Ukrainian ships through the mouth of the Bystroye is almost half the cost of sailing the Sulina Canal.

Figure 7. Traffic congestion of ships loaded with grain at the entrance into the Danube Delta in the Black Sea, 12 July 2022. Congestion in Romania’s Sulina Canal is visible. Source: Marinetraffic

Cost of building the DNC

Over the course of several years, different figures were given for the cost of building a canal via Bystroye – ranging from 38 million hryvnia in 2000 to more than 500 million hryvnia in 2007. But these expenses cannot be considered final. After all, the channel affects the full extent of the Danube Delta – a powerful river that transports a huge amount of suspended particles and sand. As a result, the channel requires constant dredging and, consequently, ongoing spending.

Each year, the Danube deposits an impressive amount of sediment and dissolved minerals into the Black Sea – about 120 million tons. All these sediments settle either at the bottom of the channel or on the sea shelf. It is no surprise that relentless dredging becomes the most expensive part of its operations plan.

For example, in the first years of operation and according to plans, expenses for maintenance dredging annually exceeded 10 million hryvnia. In addition, additional total annual operating costs totaled approximately 25 million hryvnia (according to the project’s designers).

During construction, Ukraine’s Ministry of Transport and Communications stated that the project would begin to generate income after three years of operation. However, one season was all that was needed for the DNC to become choked with silt and lose the depth necessary for the passage of cargo ships. State-owned Delta-Pilot, the company responsible for the channel’s construction, conducted ultra-costly dredging several times (notably, the price for removal of a single cubic meter of soil rose from €1.5 to €10 between 2004 and 2006), but from the autumn storm season until spring, the Danube replaced all the sediment that had been removed previously.

During the first two years of the canal’s operation, total direct losses (increasing the cost of construction) amounted to roughly 200 million hryvnia. State company Delta-Lotsman, which implemented the project, counted its losses year after year and ended up in debt. The general contractor’s services – German company Josef Möbius Bau-Aktiengesellschaft – were not fully paid either. Ultimately, the debt was cleared in 2021 by a transfer of the property to the Ukrainian Sea Ports Administration.

While the economic viability of building the DNC became more and more illusory, the environmentalists’ warnings were coming true.

Why environmentalists are sounding the alarm

First, as is often the case in inland waterway construction projects, hydromorphological changes emerged. Sediments from the mouth of the Bystroye need to be directed deeper into the sea to avoid interfering with ship movements. Usually, a marine approach channel is built for this, which is, as it were, a continuation of the riverbed. This tactic was used for the Sulina channel.

In the first decade of the 2000s, Romanians were forced to build a system of dikes five-kilometers deep into the sea to protect the canal from sedimentation. This permits an assumption that the Danube-Black Sea DNC’s approach channel will also not be limited to the modern 3.4 km. Digging such a trench requires lifting tons of biomass found on the seafloor (benthos) and an enormous amount of sediment that has accumulated there over the centuries.

As a result, populations of several sturgeon species may be affected by dredging, migrating upstream and downstream depending on the time of year. This is due to the fact that the number of benthic invertebrates (food supply for sturgeons) will significantly decline due to dredging carried out by Ukraine.

In addition, sturgeon are protected not only by national and international regulations, but also by special international agreements.

Although scientists have documented the critical population status of all sturgeon species, it is difficult to determine the role of Ukrainian construction of the DNC. However, it is known that their population migrates via the Ukrainian Kiliya branch of the Danube.

But sturgeon are not the only issue. In its report, the Romanian government provides data on the project’s impact on 78% of bird species nesting in Musura Bay, 15 km from where the Bystroye drains into the Black Sea. The construction of the DNC also disturbed colonies of terns that abandoned their nests during an active phase of construction. It should be recalled that mass nesting of bird colonies in the past was a reason for the creation of the transboundary biosphere reserve.

The DNC’s construction involved a 2.73 km long dike in the offshore approach to the canal because the nearby coastline was significantly eroded. The region’s specifics forced planners to accept an increase in the anthropogenic load on an already controversial project. About half of the coastal area is subject to erosive processes; there are approximately 3,500 landslide-prone areas. In addition to stabilizing slopes from wave erosion, the dike was supposed to protect ships from drift currents and winds. The dike is actually essentially perpendicular to the sea currents crossing the Danube Delta from north to south. Construction of the second dike is listed in Phase 2 plans. It should be noted, however, that dikes actually introduce the largest change in sediment flow.

So what is the significance of river sediments carried by the current to the sea? It is the deposits of river sand that shape the coastline’s geography in the deltas. For example, Bird Island Spit (destroyed as a result of construction of the DNC, as seen on satellite images before and after its construction) was formed by sediments carried from the mouth of Bystroye by sea currents from north to south. The northern dike will intensify the spit’s erosion process, while construction of a dike in the south will accelerate siltation at the mouth of the delta and in the underwater channel.

Satellite images of Bird Island Spit before and after DNC construction

But the list of problems accompanying construction of the DNC at the mouth of the Bystroye does not end there. Construction of a new port (as planned during final project implementation) could cause irreparable damage to river ecosystems. There is every reason to seriously question this project.

With the outbreak of the full-scale war in 2022, Ukraine’s government adopted amendments to a number of laws regarding the regulation of land relations under martial law. According to that regulation, it is now possible to use lands within protected areas for the construction of seaports and commercial agricultural production. It could be hoped that the issue is not about the Danube Delta, but rather the same law introducing a very specific change into transitional provisions in Ukraine’s Land Code. During martial law, “the transfer of government-owned property, and offering communal property for rent is permitted… for siting river ports (terminals) on the Danube River….” Construction of river ports on the Danube was legally impossible until 2022, but now the rules have changed.

At the same time, a former commercial seaport located at the 27-km waypoint along the Danube River is the Kiliya terminal at Ust-Danube’s port today. The Kiliya terminal has a fully equipped berthing line, four gantry cranes, open and closed storage areas, an elevator, and a deep-sea berth. Even in pre-war times, it was largely idle due to the lack of cargo, partly due to the fact that the Black Sea-Danube DNC at Bystroye was not capable of transiting ships of sufficient carrying capacity. The profitability of building another port is a big question and something about which environmentalists are deeply concerned.

Climate lashes the Danube. Will the project make things worse?

River shipping is a type of transportation that is highly vulnerable to climate change.

In recent decades, Europe has been facing droughts that limit traffic on the shallow Danube between July and September. This year, siltation was more significant than in 2018, when the low water period broke a 500-year record. Hundreds of ships were unable to pass through the Bulgarian and Serbian sections of the river, and these countries were forced to conduct extensive and expensive dredging in order to somehow maintain a navigable channel. Germany has closed shipping lanes for cargo transportation.

The Kiliya channel (one of its branches is the mouth of Bystroye) was once the most full-flowing branches of the Danube. Today its waters are dwindling. As early as the beginning of the 20th century, it accounted for 70 percent of the Danube’s total flow, in 2020 that number was 50 percent.

To a large extent, the reason for this is the dike built by Romania near Cape Izmail Chatal over 150 years ago. This stone structure on the Romanian coast points toward the Ukrainian side and almost reaches the middle of the channel. As a result, the share of runoff attributable to the Kiliya channel has noticeably decreased. At the same time, the share attributable to the Tulchinsky branch (on the Romanian side) increased. The redistribution of runoff in favor of Romania will accelerate Ukraine’s reckoning with the consequences of extreme droughts on the Danube.

Several studies commissioned by the European Union show that sedimentation adaptation tools are very limited. (One of these studies – “Effects of climate change on inland waterway networks” – can be viewed here.)

One possible solution may seek to reduce the draft of vessels; the Danube fleet generally has up to 2.7 m drafts, and this year’s limit is 1.7 meters. So in the future, smaller flat-bottomed vessels will have the advantage on the river, although without accounting for climate regulations their use may be economically unprofitable. It is also advisable to plan for shipping to occur only during seasons with sufficient water availability, waiting out droughts and/or using other modes of transport during low-water periods.

Intensification of dredging and even more so constructing dikes to ensure navigable depths is extremely economically costly and directly contradicts EU legislation in environmental terms. The last straw was the exclusion of dredging activities from the “green taxonomy.”

International reaction

Ukraine’s government has requested environmental reviews of DNC projects on the Danube several times. Without such evaluations, it is difficult to seek financial support for construction from international banks.

Most of the reviews noted that construction of the Bystroye DNC contradicts Ukraine’s national legislation and international agreements. The Ministry of Ecology repeatedly requested assessments of alternative projects until 2003 when expert staff at Taras Shevchenko University of Kyiv agreed on the best option for constructing a DNC at that location.

Construction of the first stage began in 2004 and was marked by the violation of approximately 20 environmental conventions, agreements, and declarations that Ukraine had previously ratified or acceded to.

The European Commission and the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube were the first to react. Non-governmental environmental organizations (Environment People Law (EPL), World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Socio-Ecological Union (RSEU), Pechenegi Environmental Group, and others) were the main international advocates representing environmental interests. WWF launched a focused campaign through its Danube-Carpathian program, providing resources for the analysis of alternative solutions and monitoring the course of events.

The Romanian government also almost immediately announced that the project was designed by Ukraine unilaterally and required additional work. They also became active participants in discussing the project in the international arena.

From May to October 2004 alone, more than 50,000 organizations and individuals from 90 countries spoke out in defense of the Danube Biosphere Reserve. Those voices were followed by decisions of the Standing Committee of the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention) and the Commission of the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context (Espoo Convention). They made the following recommendations to Ukraine:

- Halt project realization;

- Conduct public hearings and communicate with Romania (Ukraine unilaterally decided to build the canal);

- Conduct comprehensive environmental monitoring;

- Conduct a more detailed analysis of alternatives to shipping via Bystroye.

Ukraine stopped construction activity for just six months. The first phase was commissioned in 2007.

Since that time, Ukraine’s reporting process concerning implementation of the Espoo Convention during construction of the “Danube-Black Sea” DNC and environmental monitoring of the Danube Delta has been ongoing. The case of its non-compliance with the convention’s requirements remains open to this day. Ukraine is seeking a compromise for environmental solutions that will allow it to proceed to the final stage of the project.

Do alternatives exist?

Adoption of the UN’s Black Sea Grain Initiative in the summer of 2022 could become a de facto wartime alternative to the expedited construction of a canal and port in the Danube Delta Reserve’s strictly protected zone. UWEC Work Group examined this approach in October in “First wartime agreement in jeopardy?”. However, in September the Secretariat of the Danube Convention had already anticipated that the Russian Federation would not renew the agreement and held consultations with Romania and Ukraine to improve cooperation mechanisms in Danube ports.

Ukrainian shipping routes on the Danube have a cargo turnover of 10-12 million metric tons, while Romanian routes ship over 22 million tons. Considering Romania’s existing and extensive infrastructure, it seems that in the future Ukraine’s more efficient use of the Danube is possible within a cooperation framework rather than head-on neighborly competition.

In today’s circumstances (that is, the Sulina Canal being insufficient for transporting Ukrainian wartime cargo), the inevitability of developing shipping in the Ukrainian part of the delta seems obvious. But engineering errors during construction of the DNC’s first stage cast doubt on the long-term, successful existence of the Bystroye DNC. Potential contractors are, unfortunately, operating under the illusion of possibly building several more shipping channels within the Danube Reserve. It is reasonable to contemplate identifying the single most environmentally and economically justified option for developing the transport system. Highways that serve as port access roads could become a viable alternative to the canal. This is more in line with Europe’s tacit policy of phasing out inland waterways.

This option is, however, extremely environmentally unfriendly. CO2 emissions are not the only issue, but also due to the fact that new roads will have to be built to transport cargo to Ukrainian river ports; road density in this area is quite low. It is possible this will solve logistical challenges, but it will also have a negative impact on ecosystems. Exhaust, noise pollution (which disturbs bird colonies), chaotic soil dumps, and traffic hazards for wildlife are all project downsides.

Rail travel is analogous to road travel. It is a fairly acceptable alternative due to large freight turnover and relatively low cost. Even so, there are no rail routes connecting Danube ports in Ukraine today. There is active discussion on this topic.

Looking specifically at river transport, there are a number of more reliable (and well-known among specialists) alternatives to endless dredging of the channel at the mouth of Bystroye. Maintenance of deep-water navigation channel depths will soon become much more expensive for the anthropogenic and natural reasons outlined above.

The most radical of the eleven alternative long-term solutions to the problem proposed by experts is converting the large Danube-Sasyk irrigation canal into a navigable canal and installing shipping locks. The channel passes outside the reserve, mostly through previously developed areas and beyond geomorphologically active parts of the delta. It would require large initial investment, but would have greater reliability at an exponentially lower cost for maintaining navigation. In fact, it would become an analogue of the Romanian Chernovoda-Constanta Canal that currently carries most cargo, although its geographical position is less favorable.

Identifying the best alternatives for developing the transportation system remains relevant, and it is important that alternatives to river navigation be considered.

There is a sense of deja vu when it comes to controversial amendments to a number of laws and regulations relating to building activity in the Danube Delta. In 2004, a Ukrainian presidential decree threw unique river ecosystems “under the excavator.” It would be preferable to avoid additional hasty decisions fueled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The United Nations’ vision of the world at the brink of a global food crisis prompts us to think about what could be more important than this. But there is also a danger that the threat of famine could become a cover for forcing the construction of a deep navigation channel at the mouth of Bystroye at any cost. On the other hand, Ukraine’s strong support in the international arena enables it to attract scientists and experts from many countries to the search for more optimal and environmentally oriented solutions in the Danube Delta.

Main image credit: gingerwhite.co.uk

Comments on “Should Ukraine continue building the Danube canal?”