by Oleksii Vasyliuk

Translated by Nick Müller and Jennifer Castner

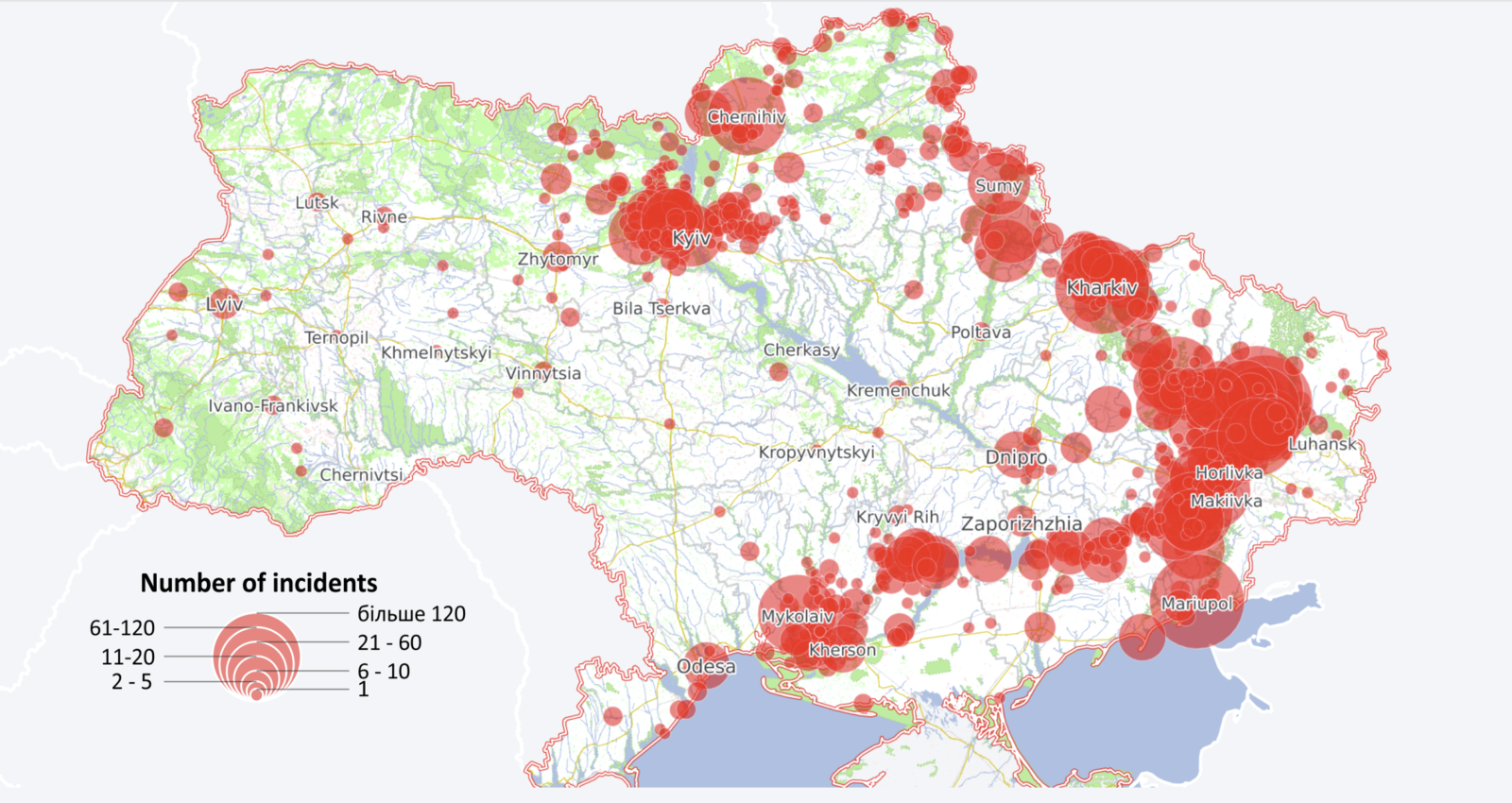

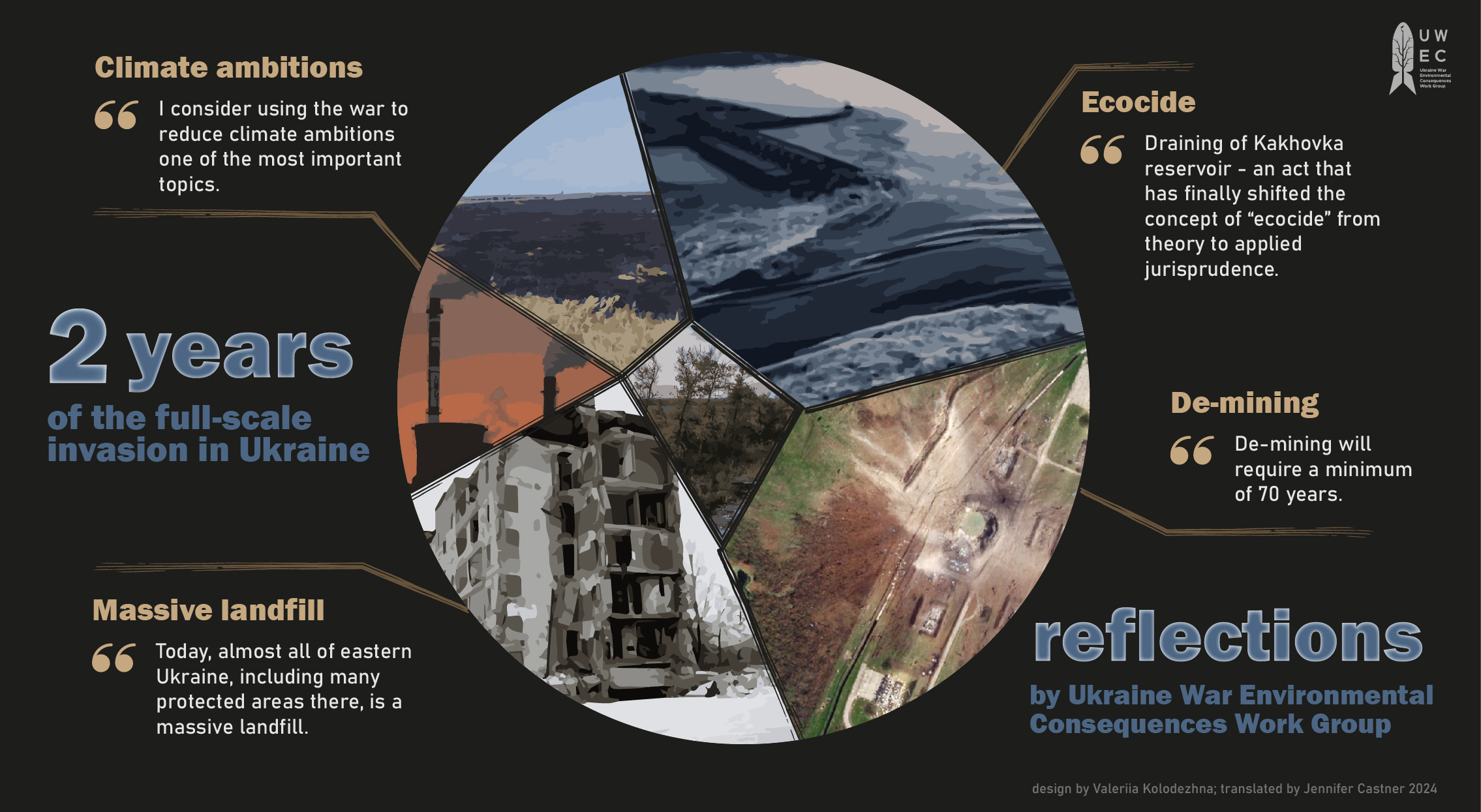

The occupation of eastern Ukraine by Russian troops in 2014 and subsequent fighting in 2014-2017 caused power outages and, as a result, flooded coal mine shafts that are concentrated in this region. This, in addition to ongoing unregulated and illegal coal-mining, poses a significant threat to the environment. The Donbas’s future is complex and requires careful planning and investment to address social, geopolitical, industrial, and environmental challenges.

Southeastern Ukraine is called Donbas, an abbreviation for “Donetsk Coal Basin”. Before the war, the vast majority of this region’s population was in one way or another involved in the mining industry, an important force for the entire socio-economic future of this region. Until 2014, over 6 million people lived here. Coal mining shaped the region and the conditions of its human settlement.

History of the problem

Its ancient mountain landscapes, aged at 150 million years, are today called the “Donetsk Ridge”, thanks to ancient large-scale erosion processes that resulted in easily accessible and large deposits of coal (including at near-surface level).

The Donetsk coal basin has been exploited since 1796. Since then, more than eight billion metric tons of coal have been mined here with the remaining reserves estimated at over 90 billion tons. With an annual production of 100 million tons, the reserves could be exploited for another 570 years.

At the same time, it was precisely this specialization of the local economy that for a long time preserved Donbas’ wild nature in the best possible way, better than in other areas. There was no agricultural development in the region, and wild natural landscapes often border directly on industry. Despite this, attempts to develop tourism in this region before the war were unsuccessful.

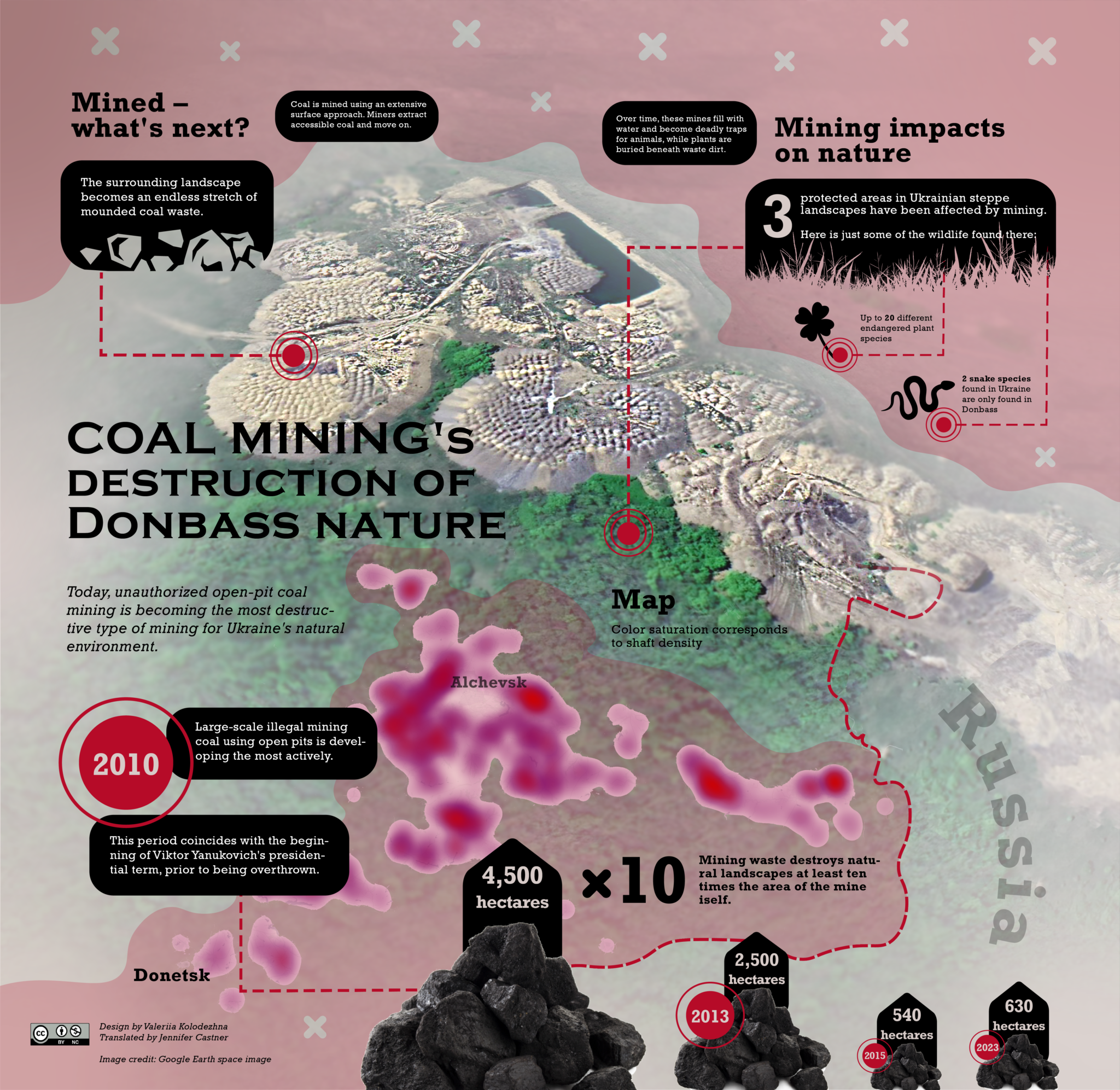

In 2013, the volume of illegal coal extraction had already reached millions of tons and, by some estimates, accounted for up to 10% of the country’s entire coal production. At the time, kopanka and mine covered roughly 2,500 hectares in total, but UWEC experts believe the size of the area to be at least 5,000 hectares. Almost all of them were in occupied territories. The largest concentrations of surface mining sites are located within the Shakhtersk-Torez-Snezhnoye agglomeration.

The most active, large-scale illegal open-pit coal mining began in 2010-2013, when Viktor Yanukovych was Ukraine’s president. An analysis of historical satellite images shows that it was during this period that most modern open pits began to be exploited and then they expanded in number from there.

Open-pit coal mining marks a new era of industry in Donbas

Development continues almost everywhere where seams can be dug up with excavator buckets. Targeted areas are found in steppes, forests, fields, and protected areas.

Photos 4-5. Coal mining pits, as a rule, consist of a 40-meter pit with sheer walls, surrounded by areas covered with rock spoil heaps. Source: Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

Since these are completely illegal activities, it is not surprising that no one is addressing the legal status of mined land or its real owners (shareholders). Large kopankas essentially consist of territorial squatting controlled by the criminal world. As a result, kopankas and open-pit mines stretch for kilometers, destroying roads, forests, steppes, and reservoirs.

Flooded mines: causes and effects

Power outages in early 2014 caused the mines to flood when power outages in lower levels of mines disabled entire water pumping systems. Everything else that occurred resulted from that process, which started nine years ago in the first days of the war.

Groundwater, if not pumped out, fills voids in mine shafts and leaches heavy metals and salts from rocks. This is the origin of “mine water” and it needs somewhere to go. Making its way as best it can through underground workings and passages, it filters through sandstone and then mixes with clean underground water, forming a toxic cocktail.

In many places, mine waters leach toxic substances out of the rock at different depths. The final phase of flooding is when mine waters reach the surface of the earth and enter into rivers, and – eventually – the Sea of Azov.

The more mines are flooded, the more kopanka mines are created.

Much of what is known about the consequences of mine flooding in Ukraine comes from the speeches of hydrogeologist and Doctor of Technical Sciences Evgeny Yakovlev. He is one of the few experts who comprehensively studies mine flooding in the country.

Yakovlev assumes that mine waters prop up underground and ground waters from below. As a consequence, the water table rises and seeps into the houses. The cities and towns of Donbas are doomed to flooding, and it is impossible to assess the pace of this seepage, since Ukraine currently does not have access to flooded mines in temporarily occupied territories.

Scientists are predicting even more alarming forecasts about future changes in Donbas’ ecological state related to flooded mines over the next 10 to 50 years:

- Land subsidence and the flooding of soils, rendering land unsuitable for agriculture;

- Pollution of drinking water in wells and reservoirs with heavy metals and minerals;

- Surface methane emissions and its entry into basements. Methane gas is combustible;

- Sinkhole formation over ore subsidence areas in mines;

- Man-made earthquakes; and, consequently,

- Mass migration of people out of the region.

Impact of open pit coal mining in protected areas

Today, unofficial open-pit coal mining is becoming the most environmentally destructive form of mining Ukraine has ever known.

Why is this happening? Take a mine shaft as an example. Its interior stretches underground for kilometers, while at ground level, one sees a spoils heap and single trunk shaft, visible from afar, at the entrance. Consider also industrial open-pit mining of ores, say, in Kryvyi Rih: a bottomless open pit with a gigantic spoils heap alongside. However, even that still occupies a limited area.

This “endless lunar landscape” forms precisely on Donetsk Ridge, where an unofficial open pit coal mine has now unfolded (the largest open pit that can be seen on remote-sensing images stretches for 15 km!). Coal is mined by an extensive surface method, digging everything that can be reached with a bulldozer, generally dozens of meters deep. They extract available material and then move on.

Such unofficial mining does not involve the construction of infrastructure or a centralized approach to managing spoil heaps. As a result, spoils are unloaded, load after load right next to the mine. In the end, the surrounding area is converted into endless heaps of stone.

Unfortunately, a number of protected areas have already been damaged in this way, including, for example, Illyriyskiy, Belorechenskiy, and Perevalskiy Refuges. These protected areas are located in the most extensive stony steppe grasslands in the Donbas, and each of them contain as many as 20 species of rare plants listed in Ukraine’s Red Book. In addition, rare snake species live here, including two snake species found only in Donbas in Ukraine. Water-filled kopankas are deadly traps for reptiles.

In terms of the extent of its ecological footprint, open mining cannot be compared to any other type of natural resource use. Indeed, in addition to development of fossil fuels, spoils storage destroys an area of wilderness at least ten times the size of the mine itself.

The main focus here is on intact natural areas, which are thick on the ground on Donetsk Ridge. Natural environments only undergo this mining method in the occupied territories. There are no kopankas anywhere else in protected areas of Ukraine and there have never been because coal seams run more deeply elsewhere.

Consequences of surface coal mining for community life in Donbas

The loss of mining jobs, which for several generations served as the primary occupation among a significant part of the population, left people with nothing but to work in the kopankas, as most of them cannot imagine another life. Mining work is also very dangerous and unhealthy.

Aside from the absence of other employment opportunities in occupied territories, there are also psychological factors to consider. For generations in the Donbas, propaganda has portrayed miners as the chosen ones, heroes, and incredibly courageous people. It was also extremely difficult for many to refuse this imposed heroic “calling”. In reality, this dangerous and health-destroying profession simply exploited millions of workers.

Illegal coal mining is carried out in the absence of any labor safety standards, either in kopankas or in abandoned mines. These inhumane work conditions were even used to represent suppression of the psyche and the instinct of self-preservation from hard work in the scandalous film “Death of a Worker” directed by Mikhail Glavogger (2005).

In the past, there were also known cases of minors working in kopankas. There have been reports about child labor (boys aged 13 to 15 years) in kopankas in the cities of Anthracite, Rovenki, Makiivka, and Snezhnoye.

Kopankas in geopolitics

The situation in the coal industry changed dramatically in 2014. Not as a result of any reforms, but in connection to military operations in Ukraine. When the part of Donbas where kopankas were distributed fell under the control of illegal armed groups in the so-called Luhansk and Donetsk Peoples’ Republics (LPR/DPR), the issue of illegal coal mining moved to another level for Ukraine. Now, coal mining has become officially illegal not only in artisanal mines (“holes”), but also in state mines seized by illegal armed groups located in occupied territory.

There are also many nuances to consider as well. Indeed, there is still no law that would clearly regulate the country’s relations with parts of Ukraine where Kyiv has lost control. As a result, trains bearing coal traveled into Ukraine from the occupied territories almost daily until 2017.

Until a certain time, there were no formal reasons for a ban on coal imports from LPR/DPR. Both places – here and there – are Ukrainian territory. Most of the enterprises operating today on the other side of the front line possessed Ukrainian registration documents. But Ukraine’s government simply did not have the capacity to monitor mines producing coal imported from LPR/DPR or to know who runs these businesses.

As a result, a logical question arose as to what extent the existence of the occupation regime depends on coal sales earned from coal sales on territory controlled by Ukraine. After all, the true owners of the various LLCs operating on separatist-controlled territory were most often field commanders of the self-proclaimed republics or businessmen close to them, paying lucrative sums to criminals for the opportunity to trade.

Of the 14 thermal power plants (TPPs) that operated in Ukraine before the full-scale invasion, seven are fueled by grade A anthracite, coal that is largely mined in the eastern part of the country, including in the calamitous kopankas. Coal mining in mines previously closed comprise another shadow segment of the coal industry. The seams in these had not yet been fully exploited before closing, but all the equipment necessary for the mine’s operation and safety was removed.

For some time the Ukrainian government has argued that buying coal from illegal armed groups was a necessary measure, without which the nation’s power plants could not function and people would freeze in the winter months. However, it quickly became clear that coal was purchased not only to fuel thermal power plants, but also for industrial use in other parts of the country, and train cars of coal crossed freely over the demarcation line in response to demand.

Since 2014, the armed groups in the LPR/DPR have also controlled surface mining operations. Unlike official mines that have significantly reduced production due to occupation, flooding, and fighting, barbaric surface mining has maintained the industrial scale it achieved under Yanukovych and now represents a significant share of coal production in the self-proclaimed republics.

In March 2017, units of Ukraine’s National Guard began to block coal trains coming from occupied territories. This blockade was motivated by the understanding that purchasing coal from the self-proclaimed republics (which “nationalized” all mines) is essentially financing separatism and the war against Ukraine. In response, coal from occupied territories but registered as having been produced in the Russian Federation began to be exported to Central European nations. This occurred despite the fact that most mines, including the largest, were no longer operating.

A significant share of the coal was obtained by unregulated, illegal coal mining in both open pits and in makeshift kopanka mines, often created by Donbas residents not only in natural areas, but even just in their own backyards.

The mines that continued to operate used the same illegal re-export channels via Russia and Belarus to reach the European Union. European journalists often, for example, in 2019, counted as many as 5,250 train cars of coal per day leaving occupied territory and heading for Russia. Interestingly, falsification of coal product origins means that Belarus, which does not possess a single coal mine, has become one of the largest exporters of coal to Europe.

While the loss of mines, infrastructure destruction, and blockade of re-export opportunities, has changed big business interests in Donbas coal, life has become ever more challenging for residents who remained in mining towns and villages. As a result, in recent years, illegal coal mining has developed such that instead of a small number of large mines requiring heavy equipment, enormous numbers of illicit digs (or, as local residents call them, “holes”) began to arise.

The events of 2022 greatly altered the situation. Mass conscription among the Donetsk residents living in occupied territories for military service in the DPR armed services has occupied most of the region’s able-bodied male population. Russia sends these military units to battle against Ukrainian troops, and, as a result, they have suffered almost the greatest losses. It is likely no men are available to work in the kopankas. Apart from children…

Conclusion

Donbas faces large-scale changes in the future, and not only in social and geopolitical terms. Rapid degradation of infrastructure, population out-migration, and likely significant changes in societal organization distance Donbas more and more from its recent industrial past. Subsequent advances of the frontline toward Ukraine’s 1991 national borders will further intensify these factors. It is difficult to say how realistic it will be to restore mines in the future (or to create new ones), but interest in coal reserves will undoubtedly remain. There is a high probability that the threat of open-pit coal mining will persist, since even near-term liberation of temporarily occupied territories will not address the issue of access to flooded mines.

To prevent this threat, in 2020 Ukraine’s Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources supported scientist proposals and turned to the Berne Convention Permanent Committee with a request to include the vast natural massifs of Donetsk Ridge in Europe’s Emerald Network. At the moment when Ukraine becomes a European Union member, these territories will be no less important than national parks and reserves. The proposal was accepted in 2021 and now the majority of Donbas nature is already categorized as a “Nominated” Emerald Network site, a move which requires establishing conservation measures. Unfortunately, the decision was made when the territory was already temporarily (and remains) out of Ukraine’s control. Nevertheless, any and all coal mining in Donbas can already be recognized as a clear violation of international law. UWEC Work Group hopes that the resumption of Ukrainian control over its territory and its subsequent European integration will end destructive coal mining.

Main image: The Donbas region grew up around coal-mining, and these spoil heaps became a hallmark of the local landscape. Source: Valeriy Ded, CC-BY-3.0

Comment on “Unregulated coal mining destroys Donbas nature”