Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Eugene Simonov

The decentralization of Ukraine’s energy sector, which has gained new impetus in 2024 as a result of Russian missile attacks, is currently the subject of intense discussion – one which has an important environmental dimension. Using solar energy as an example, this article analyzes possible ways forward for the development of renewable energy sources in Ukraine and examines the challenges that must be overcome in order to quickly resolve the conflict between the need for renewable energy and nature conservation in the country.

Decentralizing everything but energy

In 2014, Ukraine finally signed an Association Agreement with the EU, marking the official beginning of the country’s journey toward European integration. Among the many specific legislative amendments provided for in the agreement, perhaps the most fundamental was decentralization, currently one of the most important areas of reform in Ukraine.

The decision to move away from vertical government and the decentralization of budget flows and taxes, coupled with a significant widening of decision-making capabilities at a local level, has breathed new life into the regions and instilled belief in the capacity of local authorities to self-govern. Administrative decentralization followed, as a result of which Ukraine has been divided into hromady (communities) – a completely new type of administrative unit, with new borders and judicial capabilities. The process of transferring land in the hromady into communal ownership is now underway.

But decentralization has yet to reach the energy sector. This is owing largely to the way the power network was developed in Ukraine – as it was all over the USSR – during industrialization in the mid-20th century. The network was based on providing cities with heat and electricity supplied by large-scale energy hubs: large nuclear power plants, hydroelectric and thermal power plants. In these circumstances, small power plants were not traditionally assigned any importance and were seen as either a source of profit for their owners or as a kind of symbolic gesture to global trends for the development of green energy. The country’s national energy network, which includes large nuclear power plants, hydroelectric power plants and thermal power plants, continues to play the main economic role.

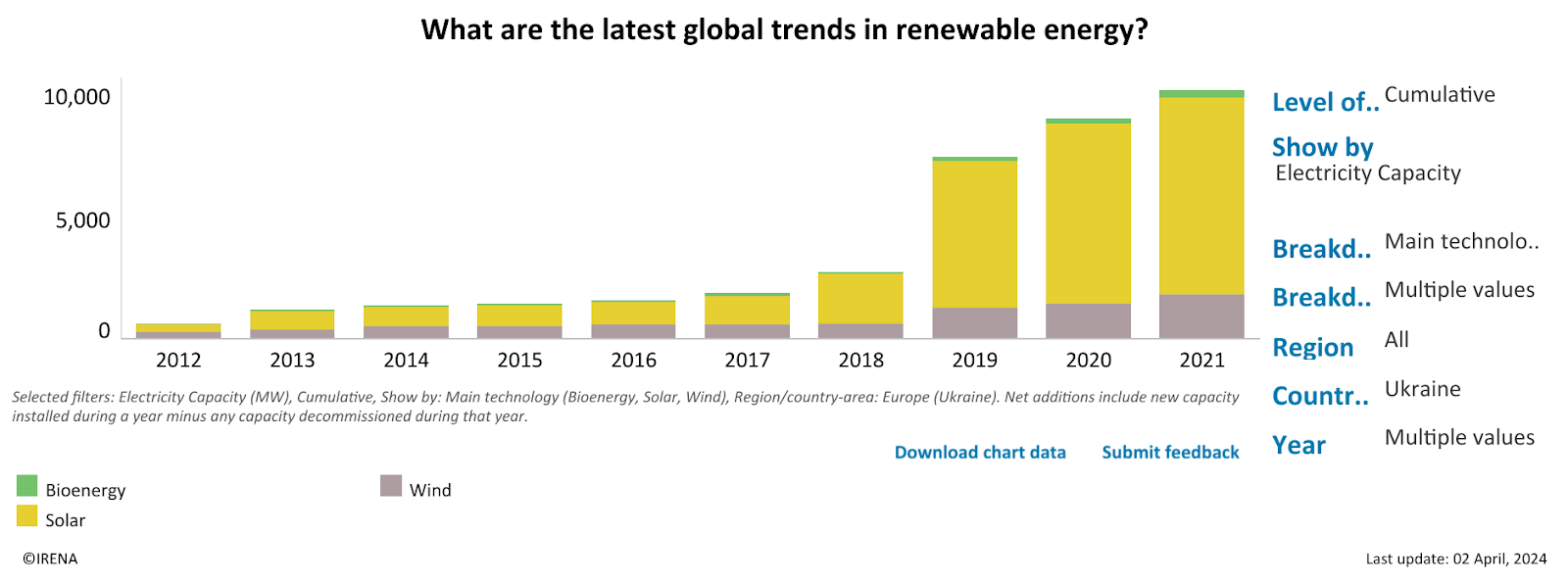

Nonetheless, Ukraine’s rapid development of green distributed generation has set it apart among post-Soviet countries. It has introduced a “green tariff” and set up a technological support base. From 2011 to 2022, solar power plants (SPPs) with a combined capacity of 8 GW were put into commission, five times more than in vast Russia (1.66 GW) and 50 times more than in comparably-sized Belarus (160 MW). Most of Ukraine’s renewable energy plants were built in the south of the country, with its optimal solar radiation conditions and the steady winds characteristic of the steppe climate zone.

Renewable energy and nature conservation in Ukraine

However, the development of renewable energy was not accompanied by reasonable environmental requirements, especially when it came to the selection of sites for new facilities, bringing the goals of economic decarbonization and environmental protection into conflict.

The south of Ukraine, which is the most suitable area for the construction of wind turbines and solar power plants, remains the most agricultural part of the country, with up to 80% of land used for crop farming in some areas. There are very few natural areas left in the south and they are constantly shrinking due to crop farming. Yet the ban on the use of agricultural land for energy and industrial needs and limited opportunities to situate renewable energy sources in populated areas mean these last remaining natural areas are essentially the only places where large solar power plants can be located. The hromady had no incentives (and nothing has changed) to preserve the remnants of southern Ukraine’s distinctive ravine-based balka steppe ecosystems (a balka is a level, dry turf-covered river valley with seasonal water flow) and happily surrender them for development. The state does not fund nature conservation, and residents of agricultural regions still subscribe to Soviet-era mantras that all available land should be used.

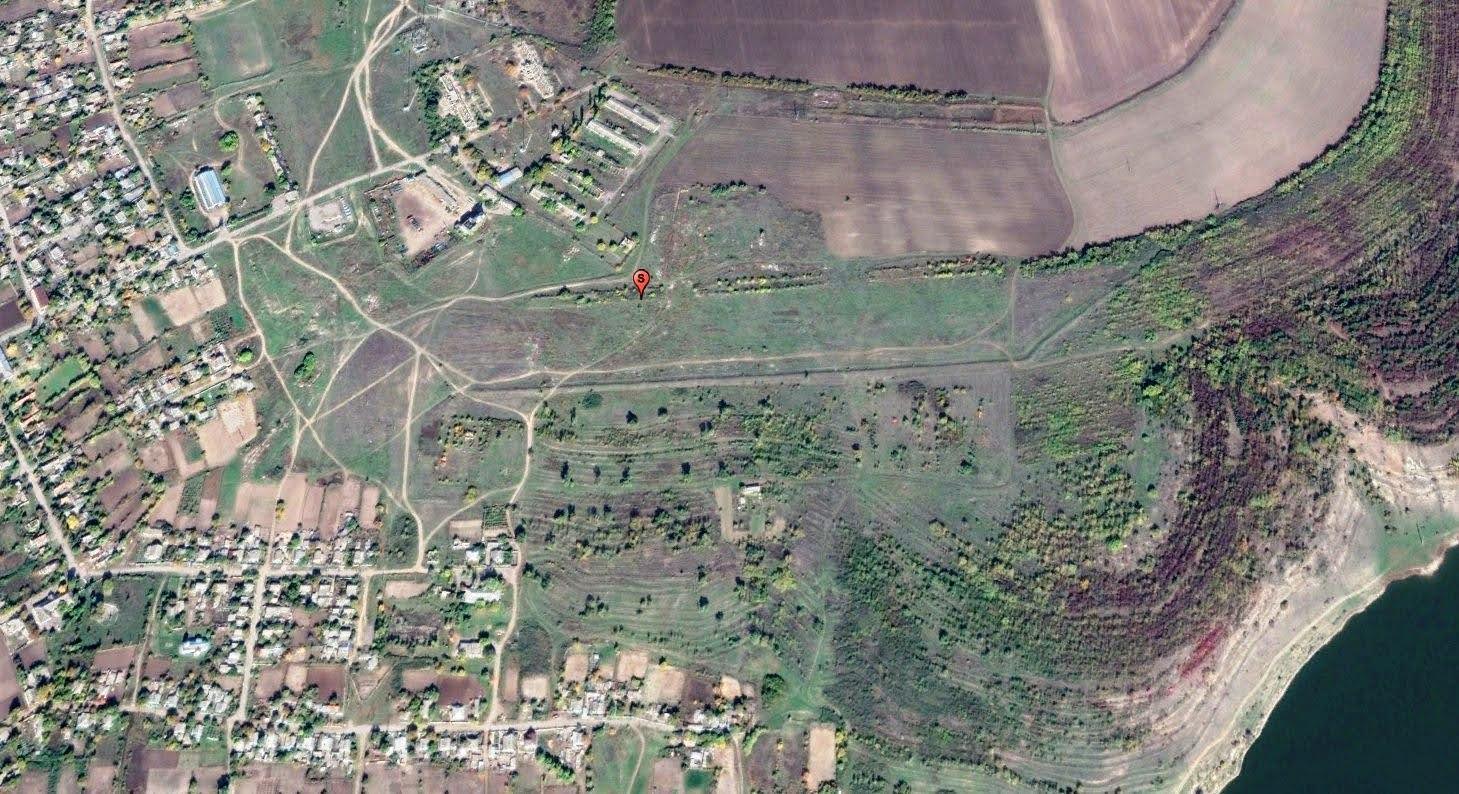

Fig. 2. The construction of a solar power plant on the slopes of a steppe ravine in the Mykolaiv region, as recorded in satellite images from 2018 and 2020. Source: Google Maps

The situation is aggravated by the fact that under Ukrainian legislation, SPP projects are not subject to an environmental impact assessment (EIA), meaning that conflicts with protected areas and other environmental harm caused by their construction are not taken into consideration. Often, environmentalists only learn about the construction of a solar power plant in a nature reserve or national park after it has been put into operation. At the same time, the laws do not provide any alternative mechanisms for resolving such conflicts in advance. As a result, remnants of natural steppes, ravine, or sand dune ecosystems, floodplain meadows, and even parts of local reserves and natural monuments were often allocated as sites for the construction of solar power plants – the Stepnohirsk reserve in the Zaporizhzhia region, for example.

Fig. 3. The construction of a solar power plant on the sandy steppes of Lower Dnipro National Park in Kherson Oblast, as recorded in satellite images from 2018 and 2022. Source: Google Maps

Why energy decentralization is feasible – and desirable

In the spring of 2024 Russia embarked on its second serious attempt to destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, and the country was faced once again with the task of restoring and bolstering the resilience of the energy network. While, after the Russian attacks of winter-spring 2023 the swift restoration of centralized energy resources was seen as the sole solution, in 2024 a number of high-ranking officials have already spoken out in favor of redirecting resources to the rapid creation of distributed generation.

“When we have 5-10 large power plants, then they are targets and can be hit. When we have hundreds of small power plants, attacking small objects with missiles will be basically unrealistic or extremely expensive,” said Andriy Herus, Chairman of the Committee on Energy, Housing, and Utilities in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Volodymyr Kudrytskiy, head of state-owned energy company Ukrenergo, also spoke about the need to urgently establish distributed generation in the country.

In the economic sense this is a perfectly viable idea, since in the course of 2023 solar panels have again almost halved in price, as a result of which a total of 473 GW of new renewable energy capacity has been commissioned around the world. Of this, 346 GW is produced by solar power plants, which has made solar power the world leader among all renewable sources in terms of installed capacity. For Ukraine, it appears that creating a network of 100 solar power plants with battery storage will be cheaper than restoring destroyed thermal power plants and hydroelectric power plants (which will only become a renewed target for missile attacks). The energy system will still need some additional maneuverability, but once it is connected with the European Union grid, this problem will probably be easier to solve using on-demand energy transmission.

It should be acknowledged that some SPPs, even those located deep in the Ukrainian rear, have been purposefully targeted and destroyed by missile strikes (in the Kharkiv, Dnipro and Mykolaiv oblasts, among others). Solar power plants near the town of Oleshky in Kherson region were also ruined, as they were located in the zone inundated by floodwaters from the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant. But damaged solar power plants require minimal time for restoration, since all that is needed is to install new standard modules to replace the broken ones.

Fig. 4. Results of a missile attack on a solar power plant in Merefa, Kharkiv region. Source: Zmina

Ukraine’s transition to renewable energy sources will reduce the cost of energy supply, lower greenhouse gas emissions and make the energy system more inclusive: it will be directly owned by the population, not just by corporations. However, to ensure that this transformation does not destroy biodiversity and ecosystem functions, it is essential that energy development programs are harmonized with the tasks of protecting wildlife.

Green transition and nature conservation in the EU

The European Union, for which the war has also raised questions of energy security, has taken a number of radical steps to hasten the commissioning of renewable energy sources. For instance, Brussels has abolished the requirements for conducting an EIA for renewable energy projects located in zones specially designated for the development of electricity generation. It was assumed that when conducting strategic environmental assessments (SEA), countries would ensure in advance that locations selected for large renewable energy facilities did not conflict with other interests (such as environmental). Considering that by 2050, renewable energy facilities will need to cover an area equal in size to Sweden in order to cover the EU’s needs, this is no easy task.

Read more:

Environmental organizations consistently criticize the acute weakening of environmental standards, since the SEA process cannot assess all specific local risks, and it does not offer the same mechanisms for public participation and control as EIA. In a recent report, CEE Bankwatch proposed a phased approach to hastening the introduction of renewable energy sources, with a first stage focused on installing renewable energy sources in already intensively developed areas. This will give time for mapping other potentially “conflict-free” territories and for public discussion of the acceptability of locating renewable energy facilities in each of them. At the first stage, priority should be given to decentralized energy in the form of solar panels and heat pumps, which will give time to prepare for the sustainable use of other types of renewable energy. On the whole, the report suggests an emphasis on the rapid deployment of solar energy as the most feasible and efficient element of the modern energy system and the creation of all possible support mechanisms for this process, including accelerated training for solar panel installers.

Other environmental organizations have already conducted comprehensive spatial analyses for the least conflict-prone placement of renewable energy sources. April 2024 saw the publication of the results of this mapping for the location of wind farms and solar power plants in 33 European countries, conducted by specialists at The Nature Conservancy. They propose a step-by-step planning algorithm that makes it possible to select areas for the development of renewable energy sources with low biodiversity value and where there is greater support for projects from the local population, which ultimately reduces the cost of projects and reduces the time needed to obtain permits for the construction of power plants.

How to create decentralized renewable energy sources in Ukraine

In order for Ukraine to accelerate its development of decentralized energy, Kyiv must establish similar safeguard mechanisms based on environmental planning and public participation. From a technological perspective, solar power is currently the preferred option for the development of renewable energy: it is the cheapest, the least vulnerable and convenient to integrate into the development of settlements and communities. A strategic environmental assessment of the available land needs to be conducted in order to identify areas most suitable for the construction of solar power plants, where there is minimal conflict with environmental concerns and the needs of the local population. It is likely that, as in the European Union, the most promising lands will be degraded areas of agricultural land located right next to populated areas.

Fig. 5. A solar power plant built on degraded agricultural lands near Shcherbani, Mykolaiv Oblast. Satellite images from 2018 and 2022. Source: Google Maps

Unlike the European Union, however, Ukraine also has the option to use land plots damaged during military operations to locate solar power plants. These can be built on the sites of buildings that are too badly damaged to be reconstructed and on agricultural land that has been hopelessly contaminated as a result of shelling. Both are often located along roads and near populated areas. It is also possible to use other anthropogenically transformed landscapes, such as slag heaps in coal mining areas. On the other hand, as large-scale restoration proceeds, it is necessary to focus not only on increasing the energy efficiency of buildings, but also for the mandatory installation of solar panels on all buildings, whether they have been repaired or are newly built.

An energy transition is impossible without public participation

The experience of democratic countries (and Ukraine itself) shows that for such programs to be effective, it is essential to have mechanisms that ensure public participation and oversight. In March 2024 the European Commission received a joint letter from European environmental NGOs with a list of demands to the Renewable Energy Guidance on Designating Renewables Acceleration Areas, which the EU is preparing to publish. The letter demands the use of scientifically based planning methods, as well as a multi-level mechanism for involving the public. On one hand, it is important to create incentives for both municipalities and individual households to use renewable energy sources. On the other hand, broad public participation is necessary in planning energy development and conducting strategic environmental assessments to select potential locations for power generation.

Restoring mechanisms for public participation in the planning and evaluation of development projects is also one of the central ideas advanced in the Environmental Compact for Ukraine report compiled by the High-Level Working Group on the Environmental Consequences of War (the Andriy Yermak and Margot Wallström Group). The report states: “Ukraine should review its laws as well as any wartime exceptions that are currently in place and make the necessary changes to ensure that all building or reconstruction projects are assessed for their environmental impacts, and that compliance with the EU’s environmental impact assessment and strategic environmental assessment directives is ensured.”

Translated by Alastair Gill

Comments on “Distributed electricity generation in Ukraine: the risks and opportunities”