Viktoria Hubareva

A year ago, the former Kakhovka Reservoir was predicted to become a lifeless desert, polluted with dangerous lakebed sediments. Instead, a unique willow-poplar forest grows there, the only such forest in all of Europe. If it can be preserved, it will bring good investments to Ukraine and have a positive climate impact.

On 6 June 2023, Russians committed a terrorist attack by sabotaging the dam at Kakhovka Hydropower Plant (HPP). This led to large-scale flooding of downstream lands. Roughly 16,000 people lived in the disaster area and about 80 settlements were in the flood zone. Water covered agricultural fields, private homes, industrial enterprises, and infrastructure sites. According to preliminary estimates, the total losses amounted to approximately two billion US dollars.

The dam’s collapse caused an ecological disaster. At least four national parks, a biosphere reserve, and other areas protected under the Ramsar and Bern Conventions were damaged.

Immediately following the disaster, many voiced unfavorable predictions, one of them being the formation of a desert on the former Kakhovka Reservoir’s lakebed. Some spoke of sandstorms that would scatter dangerous sediments that had for years been accumulating at the bottom of the reservoir. These forecasts did not come true.

UWEC Work Group spoke with Ukrainian scientists who took part in expeditions to the former Kakhovka Reservoir to learn about events at the site of the largest environmental disaster of the last year.

“In fact, it was quite difficult to reach Kamyanska Sich. But we managed, despite the danger.”

Research began even before Kakhovka HPP was sabotaged, almost immediately after the Dnipro River’s right bank was liberated in the Kherson region. At that time, scientists were studying post-belligerence landscapes—landscape complexes that arise as a result of military activity—and the war’s other consequences until the moment that the Kakhovka catastrophe occurred.

The first expedition to set out following the Russian terrorist attack headed to the de-occupied Kamyanska Sich National Park, a protected area located on the shores of the former Kakhovka Reservoir. This was three weeks after the disaster.

“In fact, it was quite difficult to gain access to Kamyanska Sich. But we managed, despite the danger,” said Anna Kuzemko, Doctor of Biological Sciences, who participated in the expeditions along with her colleagues.

The expedition organizers were Ivan Moisienko and Oleksandr Khodosovtsev (members of Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group), professors at Kherson State University, and Kamyanska Sich National Park staff, as well as geobotanist-ecologist, National Academy of Sciences Academician Yakov Didukh. Despite the importance of the research, the scientists nevertheless had to obtain permits and jump through bureaucratic hoops, but in the end, the expeditions got underway.

At first, everyone feared dust storms and subsequently that the young vegetation would not survive the winter. But the skeptics’ fears did not come true.

Anna shared that with each subsequent trip they worried less and less about the environment. All the pessimistic predictions uttered immediately following the disaster gradually dissipated.

“There were concerns that the silt that had accumulated on the bottom of the reservoir contained many different chemicals, including dangerous ones. That it would dry out, turn into dust, and the wind would carry these substances away. But when we first got there, three weeks after the dam was blown up, we saw that the soil was very dense, and it was unlikely to mix into the air when it dried out,” says Kuzemko. “We still worried that invasive plant species such as black locust (often known as white acacia), shrubby amorpha, and American maples would grow there. But these concerns finally dissipated when we traveled there again last October and saw the young willow forest.”

The biologist continued, saying that in June 2023 they saw only small plant shoots, while, four months later, dense willow thickets grew up to two meters high. Some trees reached more than three meters in height.

But even then, skeptics could not believe what would happened at the bottom of the former Kakhovka Reservoir six months on:

“They said that the willow forest would not survive the winter, that there would be no spring floods, and it would dry up. But [in the spring – ed.] we returned and saw willow forest growing on the left bank. We saw that the growth had increased approximately 30 percent on the previous year, and that these willow thickets were in very good condition, still growing, powerful, and dense! Well… and we also saw poplar thickets near Khortytsia… All fears of dust storms, desert landscapes, and invasive species remain unfulfilled.”

A forest like no place else in Europe grows on the site of the terrorist attack

Scientists involved in Earth remote-sensing using machine learning, i.e. artificial intelligence, have created a map of the Kakhovka Reservoir biotopes using field data (the map is not yet publicly available). As of November last year, roughly 40% of the former Kakhovka Reservoir was covered with willows, poplars, and other floodplain vegetation. And this forest is only growing larger.

Researchers are currently awaiting the results of a follow-up study that will quantitatively illustrate how much the forest area expanded from October to May.

The young willow-poplar forest covering a huge denuded area that was predicted to become a desert is a unique precedent, one with no analogs anywhere in Europe. According to Kuzemko, this type of floodplain forest was typical in these areas before the reservoir was filled.

“Usually such floodplain forests are significantly altered by humans. They form only along watercourses, because further away the land is either populated, or plowed, or something else is occurring there. But these places – [where nature is restoring itself naturally- Ed.] are truly unique. In Ukraine, and I think the same is true for Europe too, there are no analogs on the scale of this willow-poplar forest,” she explains.

“Imagine a willow that has grown 4.7 meters tall in less than a year! We compared this with other data and have not found comparable growth rates anywhere else,” Ivan Moisienko commented. Colleague Yakov Didukh, who studied the biomass of young willows and poplars, says that willows on the former Kakhovka Reservoir are growing twice as fast as willows growing anywhere else in the world. Southern Ukraine’s fertile steppe soils and abundant nourishing silt at the bottom of the former reservoir are the reasons for this.

It is also important that the forest’s conservation status grows as rapidly as the forest itself. The type of biotopes protected by the Bern Convention are replacing an ecological disaster site.

“Over time, the value of these territories will only grow, as the biotopes continue to develop and biodiversity increasing as well, and with that, the status of this territory in the Emerald Network,” adds Kuzemko. That is, of course, if nothing interferes with forests’ development.

Kakhovka’s willow forest has the potential to positively influence climate. Before the sabotage of the hydropower plant a “water-desert” stood here, replaced by one billion trees today

The new enormous forest will deposit carbon and store harmful substances. All of the expedition members agree on one thing: the ecosystem services that the young willow forest already provides cannot compare to those provided by the reservoir’s artificial ecosystem. The region’s climate may change for the better, all thanks to the new forest.

“These willows, poplars, and other plants at the bottom of the reservoir have already absorbed millions of tons of carbon. Carbon dioxide is the main greenhouse gas that causes global warming. I don’t know if it is possible to find another ecosystem in the world or in Europe that can fight global warming more effectively. This certainly wasn’t the case before, when the reservoir was there. Then there was a sort of, you know, ‘water-desert’ there,” explains Moisienko.

“Some believe that the climate will perhaps become more moderate now, and the number of droughts in the Kherson region will decrease,” Kuzemko comments, agreeing with her colleague.

“Well, actually, if we are talking about the need to plant a billion trees somewhere [per the President’s national program on planting a billion trees – Ed.] – they are planted in absolutely unsuitable locations – in the steppes, in sand… While here, there may already be a billion trees here on the site of the Kakhovka Reservoir. Perhaps even more. With no need for any sort of significant capital investments,” Kuzemko highlighted.

It is difficult to overestimate the usefulness of the ecosystem services that this land has begun to provide. But until recently, they were only spoken about hypothetically. Now scientists have set themselves a new goal: assess them quantitatively. One of the spring expeditions in 2024 focused on that question.

Calculating the cost of clean air, or how scientists speak the language of numbers to protect Kakhovka’s forest

After the last expedition, a video appeared on the internet showing four men trying to pull a young willow several meters tall out of the ground in the young forest. It was not an act of vandalism, but rather necessary for a scientific experiment.

Didukh explained that the tree sample will be used to study the role of willow thickets, their climate impact, climate indicators, soil formation processes, and how they consume carbon. In doing so, scientists can make forecasts for five, ten, or even 50 years into the future.

Such studies are necessary to explain the main issue to the economists, farmers, and hydrologists laying claim to the land freed from water: in its new natural state the former reservoir’s land will be much more valuable than any infrastructure facilities now and in the future.

“Environmentalists are currently trying to assemble quantitative arguments that prove the importance of these forests and not the reservoir. These people – hydrologists, farmers, economists – need numbers. We are conducting those analyses now in order to assemble those quantitative arguments and will soon publish the data we have obtained,” noted Didukh.

The team’s earlier research indicates that the ecosystem services of mature forests, if they are allowed to cover at least 30% of the former reservoir’s area, will be 16 times greater than the ecosystem services provided by an artificial reservoir.

In exchange for those services, Ukrainians can receive not only a clean, improved environment, richer biodiversity, a favorable climate, and even just a unique natural area for the world, but also very real income.

Ukrainians can earn big money from global funds by just leaving nature on the site of the former Kakhovka Reservoir alone. But there is one issue

Restoration of vegetation and the Dnipro River’s natural riverbed through the territory of the former Kakhovka Reservoir generally aligns with Europe’s “green course”, wherein other countries are striving to return rivers to their normal, natural state.

The European “Bringing nature back to our lives” initiative aims to restore 25,000 kilometers of rivers to their natural channels by 2030. The program presumes, among other things, dismantling of dams. Consequently, Ukrainian hydropower company Ukrhydroenergo’s plans to re-establish the reservoir, discussed just a month after the Kakhovka disaster, run counter to European policy of preserving biodiversity and achieving carbon neutrality. Given the pace of the reservoir’s restoration, the new project stands to nullify all that these new territories can give us if they are “untouched”.

It is the “don’t touch” option that could bring investment to Ukraine

Funds do exist in the world that are prepared to pay landowners to conduct natural restoration. The owners themselves need not do anything, simply not use the land, leave nature to be, and let it restore itself.

Seemingly, nothing better can be dreamed up for Kakhovka Reservoir. But for this to happen, several conditions are necessary.

First off, the war must end, given military actions are almost the only factor that holds these territories in a sort of limbo. Secondly, global funders must have guarantees that Ukrhydroenergo’s dreams of building a new hydropower plant will not come true.

“If such guarantees can be achieved, I think that nature restoration can be funded for many years into the future. But both the first and second conditions are difficult tasks,” Moisienko concluded.

In the meantime, all we can do is track the expeditions, wait for new research results, and watch as the ‘great meadow’ Velyky Luh (that existed here long before the creation of Kakhovka Reservoir), returns.

Translated by Jennifer Castner

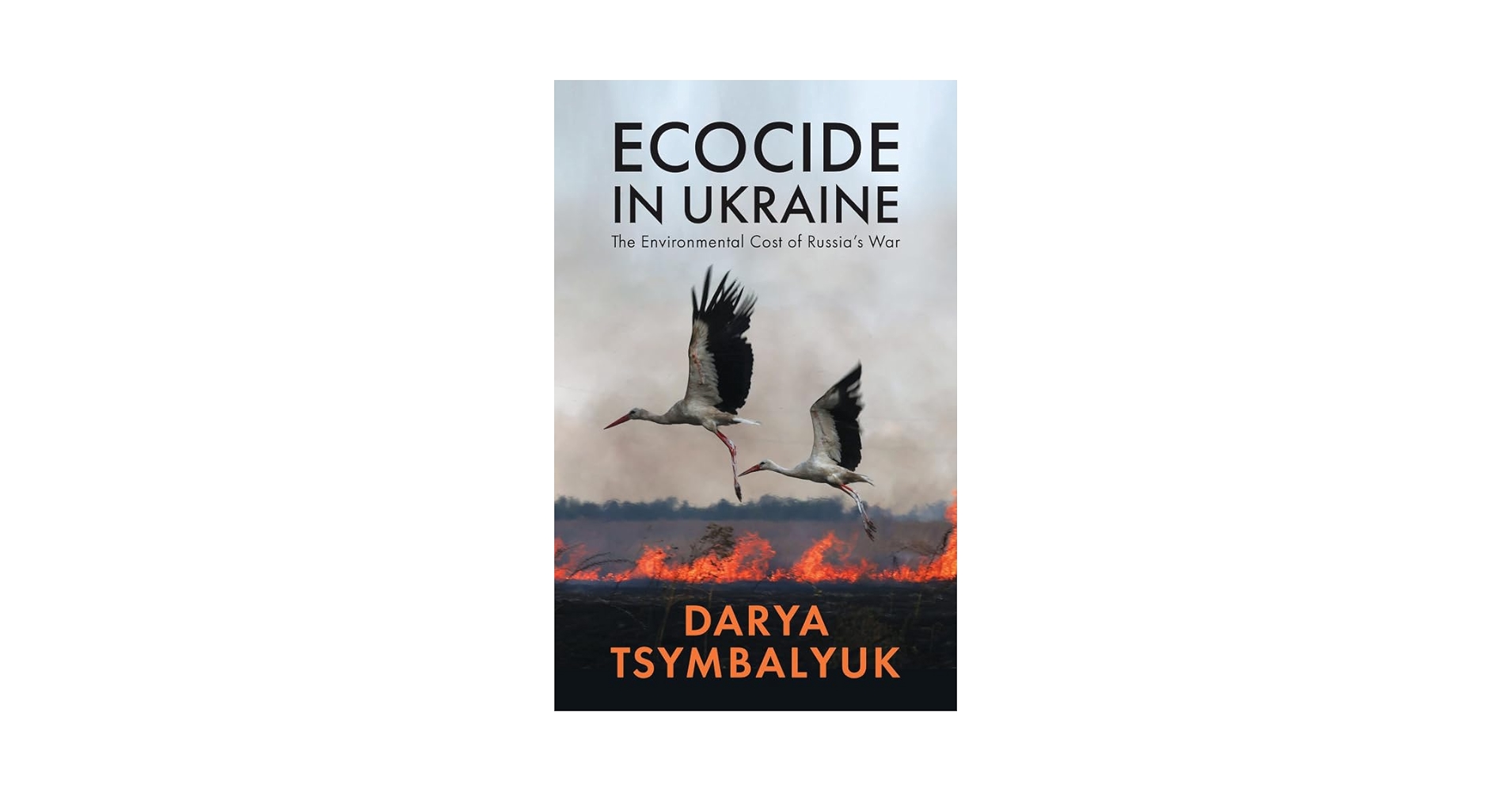

Main image: Kakhovka Reservoir, Kamyanska Sich National Park, April 2024. Photo: Ivan Moisienko