Viktoria Hubareva, Stanislav Viter

It is not only military activity that is affecting bird numbers in Ukraine – other factors are also at play. What needs to be done to ensure that birds of prey still have a place to live in the country?

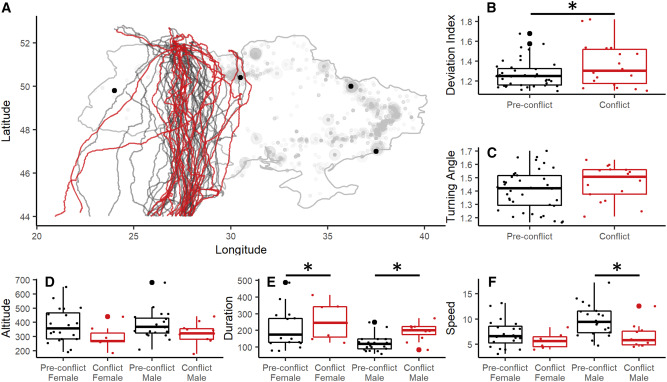

A recent story in the Ukrainian media claims that the war in Ukraine has had an impact on bird migration. The news is based upon a study in the journal Current Biology, which reports that Greater Spotted Eagles (Aquila clanga) traveled an average of 85 kilometers more than usual while crossing Ukraine in 2022, increasing their total migration time by an average of 55 hours.

As one of the few scientifically-documented changes in the animal kingdom caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the study has been seized upon by many media outlets, though they have failed to pick up on some significant details.

In order to find out what is happening to birds amid the war in Ukraine, experts from UWEC Work Group have decided to look more carefully at the issue. We should preface our report by pointing out that it is not the war alone that is affecting avian migration routes, behavior, choice of nesting sites, and reproduction. Man-made dangers can be found everywhere and are often created in the course of everyday human activities.

What does the research actually show?

A closer look at the study reveals that we are talking here about a relatively small number of Spotted Eagles that nest in the Polissia (Polesia) region, part of which includes northern Ukraine, along the border with Belarus. That is, the findings are based on a small sample from a very limited geographical area. But these are no ordinary birds. All of them were recorded using geotrackers and during migration they moved in a westerly direction – that is, in the direction of Poland.

It is therefore very unlikely that the Spotted Eagles studied flew over areas affected by military operations. In addition, it should be noted that the study compares migration routes in the years before the full-scale invasion with one season in 2022. Data for 2023 is not provided.

This has led to criticism of the publication from the scientific community. Some experts say the data presented is insufficient, while others argue that the war has no substantial influence on the migratory routes of birds, at least eagles.

“Polissia Spotted Eagles traditionally did not migrate over territories that were affected by hostilities in 2022-2024. Their migration routes lie along the Carpathian region, through Podilia [west-central and southwest Ukraine] and further through the Eastern Balkans,” says Stanislav Viter, an ornithologist with a doctoral degree in biological sciences. “Therefore, military operations have nothing to do with this. But the absence of passenger aircraft – as one type of landmark – could lead to certain changes in migration routes over the course of one season. In subsequent seasons, the birds adapted to the new conditions.”

“In 2022, I observed the same thing on the Siversky Donets [river], but already in 2023 there was a surprisingly noticeable migration even over combat zones or in close proximity to them. Species such as Buzzard, Honey Buzzard, White-tailed Eagle, Black Kite and Pygmy Eagle were also visible nesting at a distance of 20 km from the frontline,” he adds.

Viter argues that this change in migration routes was temporary, and the main factor in such changes was not in fact explosions, but the disappearance of a familiar component of air traffic for birds –passenger aircraft. The constant traffic along certain civil aviation routes in Ukraine and nearby parts of Russia served as a kind of landmark for migrating birds, which now “lacked something in the sky – something familiar and stable…”

“Changes in migration movements occurred in 2022 and lasted only one season,” the ornithologist explains. “This didn’t happen at all due to military operations or explosions, because migrating birds of prey don’t react to these explosions. In fact, no matter how creepy it sounds, they even visit battlefields to feast on fresh human flesh.”

“But already in the fall of 2023, near the city of Kharkiv, i.e. in a region directly bordering areas of very intense fighting, and where explosions are very clearly audible, I noted an intense migration of Ospreys – up to seven or even ten individuals a day – as well as Greater Spotted Eagles, common Buzzards, Honey Buzzards, Pygmy Eagles, Marsh Harrier, Black Kites,” he says.

According to Viter, the birds later managed to find the routes again, because older and more established landmarks, such as the location of the sun, the unchanging nature of river valleys and mountains, turned out to have a stronger influence.

What else could be affecting the behavior of birds?

Vitaly Grishchenko, deputy research director at the Kaniv Nature Reserve in central Ukraine, recently posted that in 2022, white storks were significantly delayed in arriving in Ukraine, looking at average arrival dates. But he puts this down to cold weather along the migration routes – “in particular, a strong cold snap in Turkey caused the birds to get ‘stuck’ for a long time before reaching the Bosphorus” – rather than the fighting. “Perhaps this also affected the spotted eagles,” he suggests.

Although humans also destroy nesting habitat in peace time, birds do, of course, suffer during military action. Black kites, studied by Czech researcher Ivan Literak since 2019, are an example of this. In the summer of 2022, these birds did not reproduce in their nesting habitat near Dvorichna village in Kharkiv region. At that time, Dvorichna was occupied by Russian troops, and today the frontline is only a few kilometers away from the population center.

“Of course, birds do not nest on the battle lines – 20-30 km wide – where the ground has been scorched bare by artillery fire,” says Stanislav Viter. “That is, if their habitat disappears and they have nowhere to nest, raise offspring, and find food, any intervention – be it fighting, a fire, or logging in the forest, even selectively, affects the behavior of birds.”

For this reason, he argues, it is important not to focus exclusively on frontline areas – there are many more threats to birds throughout Ukraine.

“I advise paying more attention to the destruction of raptor biotopes due to forest fires caused by military operations, such as in Serebryansky Forest in the Luhansk region, as well as to the destruction of raptor habitats in peacetime,” says Viter.

Even before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, the economic activities of Ukrainian entities and individuals in state-managed forests were responsible for the destruction of far more raptor nesting areas than artillery fire from the Ukrainian and Russian armies combined – in the Kharkiv region, at least.

“Also, 6-10 kW overhead power lines, which are not fitted with bird-protective devices, pose a great danger to raptors. We can add idiots with firearms deep in the rear to the list as well –after all, poachers are responsible for most of the deaths of White-tailed Sea Eagles, Golden Eagles, and Ospreys migrating from Fennoscandia [an area encompassing the Scandinavian peninsula, Finland, and Russia’s Kola peninsula and Karelia region] via Ukraine,” he explains.

Referring specifically to the effect of loud explosions as a factor in bird anxiety, Viter gives the example of the first days of the war in 2022, when the intense artillery shelling of Kharkiv caused considerable distress to Magpies and Hooded Crows.

“The birds flew nervously, screamed, and were frightened by every loud sound. Due to stress, some hooded crows lost some of their feathers, mainly from their wings and tail. But by April, at the height of the nesting season, these birds had occupied their nesting areas, got used to loud sounds, and even learned to recognize ‘arrivals’ and ‘departures’ [of missiles]: the birds barely reacted to the latter, despite the loudness of these sounds. All 20 pairs of Hooded Crows and 30 pairs of Magpies that were observed in the center of Kharkiv successfully raised their chicks, although the birds were terrified a month before nesting began,” says Viter.

What do we know about the impact of war on birds from the past?

The full-scale war has already lasted over two years, and for a decade in eastern Ukraine. While this represents a huge period of time on a human scale, it is too short for research. So it is perhaps too early to draw conclusions about how modern war actually affects bird migration.

However, we have found studies published by Sir Hugh Gladstone, a Scottish landowner who wrote a book titled Birds and the 1914-18 War, about the effects of fighting on birds during the First World War.

Although bird life was described as almost normal in the artillery zone and a short distance from the trenches, many species appeared to have been forced to leave areas destroyed by shelling. Yet the effect on bird behavior, as far as the study could tell, was extremely small, and birds in the areas where the loudest explosions occurred showed an astonishing ability to adapt to conditions that would have been considered impossible in pre-war days. The studies concluded that the birds had adapted to loud blasts and had become indifferent to the noise of battle.

Gladstone devoted a separate chapter to the impact of war on migration. The data is presented rather vaguely, and it is impossible to evaluate it from a scientific point of view. However, the author does note certain changes in migration routes – some birds chose new routes for flights, did not return from wintering, or selected new regions for nesting and raising chicks.

He writes that in 1915, in the Taurida Governorate (an administrative region of the Russian Empire that covered present-day Crimea and part of today’s Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions that did not see fighting during the war), a large number of all types of birds were observed, especially those species that migrate through the Carpathians. That is, the birds chose areas far away from the main combat zones.

“Those birds whose nests were usually situated in localities affected by the war were perforce compelled to abandon their homes and migrate to other places, thus evoking an increased flight of individual kinds of birds to certain spots.”

Gladstone also noted claims that 60 species of migratory birds stopped visiting the UK as a result of the shelling, but this thesis was soon disputed. While the book provides many interesting observations, they were collected from different eyewitnesses, so the probability of errors is high.

Gladstone quotes an unnamed French researcher who had observed significant changes in bird migration caused by the fighting in the First World War, such as wild ducks from the eastern counties of England. In 1916, instead of making their usual flight to the Netherlands and France via the North Sea – that is, directly southeast – the ducks flew first to the north, then west, and only then moved south, skirting the coast of Ireland.

Warblers from Fennoscandia migrated along the coast of the North Sea and the English Channel to the Brittany Peninsula and only then turned south, although in previous years of observation there had been widespread migration directly across the European continent. In the fall of 1915, larks and blackbirds, which usually flew through France from their breeding grounds in northern Europe to winter in the Mediterranean, bypassed war-torn eastern France and migrated through Switzerland. In 1916-1917, swallows abandoned migration to Europe in many cases and raised their chicks in Tunisia instead –halfway from their wintering grounds. White Storks were often observed in places where they usually do not nest, and in the northeast these birds left their habitual nesting grounds.

Yet Gladstone does not conclude that the war led to systemic disruptions in bird migration. After all, detailed observations on other “hot fronts” – in Mesopotamia and Palestine – showed that bird migrations continued uninterrupted in these territories.

Besides the war, what else characterizes the period of 1916-1917, when it seemed that a significant disruption of bird migration in Western Europe was being observed? Above all, the weather conditions, namely unusually cool temperatures. In 1917, for example, snow fell in London at the height of summer – in July. These weather anomalies (cold temperatures, heavy rainfall, a lack of sunny days) may have been the determining factor in the migration of shorebirds not across the continent, but along the warmer coastline, and encouraged blackbirds to take a shorter route through Switzerland. Was it the lack of real summer weather that caused the swallows to stay in northern Africa (Tunisia) and nest “halfway” home?

As for the White Storks, perhaps it was the war that played a significant role in their unusual behavior – the tendency to leave their traditional nesting sites and appear in particular places. Storks mainly nest in populated areas, and Alsace-Lorraine, the region where the bloodiest fighting of the First World War took place, is home to the largest population of these birds in France during the nesting season. Fighting in populated areas, which resulted in the direct destruction of nesting sites, may have been the most significant factor responsible for the strange behavior of these birds. Although “years without summer” certainly don’t help the species to nest. And in regions such as Palestine and Mesopotamia, which saw no changes to bird migration patterns, there were no weather shocks like those in Western Europe in 1916-1917.

What do the changes in routes and the number of migrating birds during the war tell us?

Firstly, we should not draw premature conclusions. It will only be possible to put an end to the debate among ornithologists and make final judgments after the war.

“In general, we cannot say that birds are avoiding Ukrainian territory during migration or that there is a significant reduction in their numbers. The war that is taking place on the territory of Ukraine, oddly enough, is not an event of sufficient scale to scare away migrating birds. Some birds avoid dangerous areas, others fly – everything is very individual,” says Stanislav Viter, who stresses that there are many factors that can affect the migration of birds, including weather conditions and food distribution.

“We don’t have enough data, and the impact of war on bird populations is very local, within a very narrow zone of military operations,” he says.

After the war Ukraine can begin to restore destroyed areas

It is possible to help birds restore their nesting grounds in places where their habitats have been destroyed. For example, an attempt could be made to restore Kreminski Forestry Division in the already-burned Serebryansky Forest.

“First of all, we need to cut down burned pine trees and plant new plantations that do not affect the birch, aspen, and alder groves, which are recovering well,” proposes Stanislav Viter. “Those areas of the forest that are not damaged should be left as they are. The birds will return in time. Serebryansky Forest is home to several pairs of bird, and they can nest in nearby places. The damaged area is quite limited, at least on the scale of raptor population density,” says Viter.

Assigning protected status to damaged areas

It also seems quite a logical step for Ukraine to transfer new territories to protected status.

While some suitable bird habitats have been destroyed, others which are not yet the site of human activity, can offer a new home for birds. It is extremely important to protect the natural places that we have left today.

According to biologist Oleksiy Vasyliuk, head of Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, new natural reserves would significantly improve the conditions for biodiversity in Ukraine. Such protected areas would be worthy compensation for the loss of wildlife during the full-scale war.

Restoring natural ecosystems where none previously existed, rather than simply saving the last remaining ones, is the basis of sustainable development in Europe. In recent years, European states have increasingly taken bold and far-sighted decisions to halt global climate change and guarantee a green future for the entire continent. Ukraine can and must follow this same path in order to preserve not only its birds, but also the environment itself.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image: Greater Spotted Eagle. Source: Sanjay MalikeBird S33227441 Macaulay Library ML 43621161