Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Eugene Simonov

Russia’s occupation of Crimea has paradoxically served as the catalyst for a fascinating experiment in climate adaptation. Deprived of the water it traditionally received from the Dnipro River, the arid peninsula’s economy has been forced to make do with smaller local water sources. Despite the occupation and the corruption and mismanagement it has brought, the lesson is that Crimea can rely on local resources, which give it the potential for successful, sustainable development in a free Ukraine.

Hydropolitics and war

Since the very beginning of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine back in 2014, the issue of water supply to Crimea was considered a matter of strategic importance by both Moscow and Kyiv, as well as neutral observers. Following the Russian annexation of the peninsula in 2014, Ukraine cut off the water supply to Crimea from the Dnipro River (also known as the Dnieper) via the North Crimean Canal (NCC). This has resulted in serious discussions by experts in international law, and at times Ukrainian politicians have even questioned the decision to form a blockade.

In the lead-up to and immediately after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, many international experts saw Russia’s desire to reestablish Crimea’s water supply as one of the main reasons for its escalating aggression, and as a possible bargaining chip for potential “peace negotiations”.

Immediately after the full-scale invasion, Russia tried to restore the water supply to Crimea through the NCC, but this was later interrupted once again by the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and its reservoir, which had fed the canal. Current discussions in Ukraine about the post-war future in most cases also assume that the water supply from the Dnipro to the peninsula must be restored for the normal functioning of the Crimean economy.

In this article, we attempt to look past the military and political rhetoric and discuss the changes in Crimea’s water sector over the last ten years, a period which has witnessed an unplanned experiment in climate adaptation on the dry steppe peninsula, which on average receives less than 400 mm of rainfall per year.

A very Soviet project

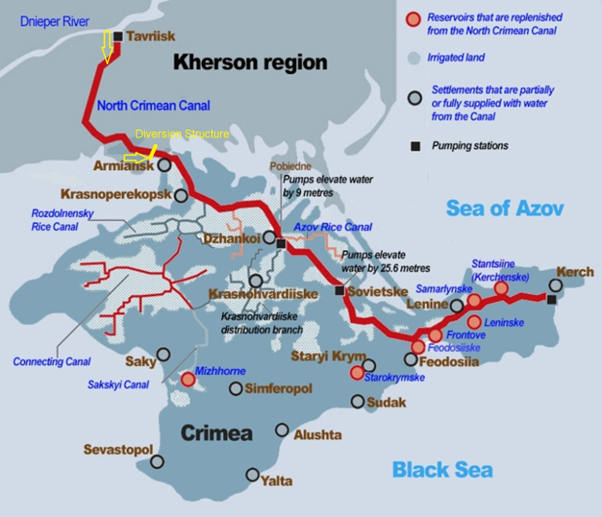

The largest canal in Europe at more than 400 kilometers long, the North Crimean Canal (NCC) separates into five large branches once in Crimea: the Azovskyi, Rozdolnenskyi, Krasnohvardiyskyi, Chornomorskyi and Sakskyi branches. These sub-canals are often referred to as the “rice canals.”

Construction of the NCC began in the 1960s, once the Kakhovka Reservoir had been filled. This was the last in a series of projects that together would create a massive irrigation system in the south of Ukraine, transforming nature on a vast scale.

When digging began, the project had no critics or opponents. At that time, there was no large-scale environmental movement in the USSR, and climate change was yet to become a serious talking point.The idea of building the NCC was based on the ideology of transforming nature to ensure maximum economic performance, without any environmental justification. The task was to turn nature into an economy, not to adapt the economy to the capabilities of natural systems. The authorities planned to use the dry steppes for large-scale rice cultivation. Ignoring modern ideas about climate, sustainable development and the fact that Ukraine is – alongside Moldova and Hungary – the most water-scarce country in Europe, the creation of rice fields in the driest part of Ukraine today looks like pure madness.

In recent years, scientists have discovered that arid (drought-ridden) climate zones in Ukraine have expanded significantly, with a consequent increase in moisture deficit. This only underlines the stark contrast between the old Soviet system of irrigated agriculture and the possibilities for sustainable development. The drier the climate, the more vulnerable inefficient irrigation systems become.

Diversion of water from the Dnipro had a large-scale impact on natural ecosystems in the north of Crimea. One of the key changes was the emergence of reed thickets, which replaced the local wetland vegetation. Before the construction of the canal, the main water body in Crimea was Lake Sivash, which is characterized by its high salt content.

Changes in ecosystems also influenced the redistribution of avifauna throughout the region. Desalination of the salty Sivash Bay and the formation of moist habitats made the territory attractive for many migratory aquatic and wetland birds. At the same time, there was a significant decrease in natural steppe areas, which led to the disappearance of steppe bird species from the region (for example, the number of Steppe Demoiselle Crane, Great Bustard, and Lesser Bustard fell significantly).

| Water body | Water taken from natural water bodies, total | Water used | Water returned to surface water bodies | |

| total | share of polluted water | |||

| Total, including: | 1553.78 | 768.56 | 208.5 | 93.17 |

| North Crimea Canal | 1346.3 | 596.5 | – | – |

| Local surface water sources | 136.38 | 113.37 | 132.7 | 84.38 |

| Groundwater | 68.54 | 56.13 | – | – |

| Sea water | 2.56 | 2.56 | 75.8 (into Black and Azov seas) | 8.79 |

Local water resources in Crimea and water consumption on the eve of annexation

Until 2014, up to 85% of Crimea’s water consumption was met through the transfer of Dnipro water through the NCC, which averaged one and a half cubic kilometers per year in volume. According to official data for 2013 from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, only half of the water taken from natural sources was used for various needs – the rest was lost on its way to consumers (see table).

Of the total volume of water consumed in Crimea in 2013 – the last year when Ukraine was able to conduct continuous statistical reporting – 590.18 million cubic meters (77%) was used for agricultural purposes, while 125.3 million cubic meters (16.4%) was consumed by housing and communal services and 50.64 million cubic meters (6.6%) by industry. At the same time, 695 million cubic meters of water was lost during transportation through the canal – almost 50%. Such high losses reflect a long-term general trend and are similar to data for 2000-2012.

Ninety percent of the water used for agriculture was spent on irrigation, with 60% (i.e. at least 350 million cubic meters) going to rice fields. Viticulture and other forms of agriculture traditionally practiced in Crimea did not require even a small fraction of the water consumed after the creation of the North Crimean Canal. Grain crop production on irrigated lands, which began in the 1960s, was completely inappropriate for local natural conditions and by 2013 only 140,000 hectares remained of the 400,000 hectares irrigated in Soviet times.

Crimea’s own water resources are relatively modest. The figure most often found in the literature is “up to 1 billion cubic meters per year.” For example, an article by scientists from Moscow State University and the Russian capital’s Institute of Water Problems indicates that after the annexation, the volume of Crimea’s own water resources ranged from 800 million cubic meters to 1.2 billion cubic meters a year. At the same time, we estimate the total guaranteed flow of rivers in Crimea as 371 million cubic meters a year, which is a very conservative estimate for conditions of extreme drought.

A total of 23 reservoirs have been built in Crimea – a centralized water source to supply the needs of the population and agriculture. Of these, eight reservoirs were filled using water from the North Crimean Canal (up to 145 million cubic meters in total), while surface runoff from the peninsula’s mountain rivers accounted for the other 15 (up to 245 million cubic meters in total). Reservoirs are critically important for meeting municipal needs, as well as for recreational and tourism infrastructure – the mainstay of the Crimean economy.

The practically endless supply of free water from the Dnipro encouraged extremely wasteful use of water resources in Crimea, so there was little incentive to think about increasing the efficiency of water use.

No water, no agriculture

Ukraine’s blocking of the canal after Russia’s annexation of Crimea was a serious test for the peninsula. By 2022, only 17,000 hectares of irrigated grain crops remained, the result of the dry local climate, which had spelled almost immediate doom for Crimea’s inefficient irrigated agriculture when Kyiv cut off supplies. Not surprisingly, it was rice cultivation that suffered the most after the supply of water from the NCC was cut off.

Local industry was also unprepared for water shortages. For example, as a result of the cessation of supplies of Dnipro water to the peninsula, the Crimean Titan plant, the largest manufacturer of titanium dioxide pigment in Eastern Europe, was forced to cut production and lay off part of its workforce.

The lack of access to water for Crimean Titan also led to environmental pollution and an ecological disaster in Armiansk in 2018, caused by the evaporation of the contents of the acid storage tank where the plant’s waste was dumped.

But the most acute problem was the provision of water to the local population and tourist facilities. In 2019-2021, scheduled supply was introduced for many settlements that received their water from reservoirs supplied by the canal. During the driest periods, access to water was limited to several hours a day in the morning and evening.

Despite the fivefold reduction in water intake, losses (the share of the volume of water intake that did not reach consumers) still amounted to 45% in 2014 (140 out of 310 million cubic meters – see diagrams above).

To reduce water shortages, in October 2020, the Russian government approved a comprehensive plan to ensure reliable water supply to the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol. The plan involved spending more than $600 million on a wide range of measures to improve the efficiency of existing water resources and finding new ones. These measures to reduce losses in water supply networks should have saved 12 million cubic meters per year, and improving the operation of existing water intakes should have provided an additional 10 million cubic meters per year.

Diverting water from the Belbek River into the dry Mizhhorne Reservoir could provide 15 million cubic meters per year, and the exploration and installation of new underground water intakes can provide 25 million cubic meters per year. The innovative plan also envisaged the creation of desalination facilities (a first for the region) with an annual capacity of 15 million cubic meters, and even included the reuse of treated wastewater from Sevastopol for technical needs. Taken together, all these measures should have increased the annual supply of water by 112 million cubic meters. This would be sufficient to solve most problems, except for the restoration of large-scale irrigated agriculture of the Soviet type.

As usual, however, even the Russian government’s best-intentioned programs are undermined by mismanagement and endemic corruption. An investigation conducted in 2021 by the publication Dictaphone demonstrated that most of the planned projects were never begun, and some of the money vanished into the pockets of the engineers without any result.

Some facilities, such as the Beshterek-Zuyskyi water intake for Simferopol and the water intake on the Belbek River for Sevastopol, were nonetheless built and put into operation. Construction is also currently underway on a 200-kilometer underground water pipeline from 38 new wells for industrial extraction of groundwater to supply Feodosia and Sudak in the east of Crimea. A 7-kilometer tunnel under Mount Ai-Petri is also being built to supply water to the resort city of Yalta. However, it is worth noting that work has already begun on implementation of the most capital-intensive projects, which are easier to use in corrupt schemes, while the most important work on the widespread replacement of leaky pipes has been put on hold.

Crimea under occupation: taking the easy route

The seizure of the peninsula by Russian troops and the resumption of water supply through the NCC to Crimea in February 2022 gave the Russian authorities a feeling of long-awaited revenge, but had a demotivating effect when it came to their readiness to implement the planned system of measures to make Crimea water self-sufficient. In March 2022, the Russian government of occupied Crimea announced that it had no plans to build desalination plants and ordered that they be excluded from state programs. The treatment and use of wastewater was also no longer prioritized. After all, “free” water from the Dnipro was once again flowing to Crimea.

However, many large construction contracts for alternative water supply systems had already been completed with influential companies, and the creation of some of the water supply projects continued after 22 February 2022. In addition, officials were anticipating gigantic contracts for the modernization of the leaky NCC and its huge network of “rice” canals, which have fallen into disrepair: tasty projects offering maximum opportunities for corruption.

In June 2023, after the Kakhovka Dam was sabotaged, the mouth of the canal quickly dried up and Moscow returned to its former talk of “water self-sufficiency” for Crimea. In August 2023, the Russian “head of the Republic of Crimea” Sergei Aksyonov declared that, apart from irrigation, the peninsula no longer needed water from the Dnipro.

The occupying authorities appear to believe that the 240 million cubic meters of water currently in storage will be enough to last the Crimean economy one year. In all likelihood it is. But it should be taken into account that this reserve was built up in 2023, the last water-abundant year, and in drought conditions additional measures will be required. These have already been outlined in the comprehensive plan to ensure reliable water supply to the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol.

Ensuring a sustainable future

Leaving aside the political value of the “umbilical cord” between the rest of Ukraine and Crimea that the North Crimean Canal provides in the public imagination, it is also important to consider the possibilities and prospects for water supply based on natural conditions, socio-economic priorities, and modern technologies.

In 2022, prominent water management scientist Igor Zonn published an interesting article comparing water management in Crimea with that in Israel, which has less precipitation but similar water resources.

The article explains that the combination of effective innovative water management with the development and use of modern technologies makes Israel not only a water self-sufficient state with a large agricultural sector, but also a water exporter. Tel Aviv has achieved this under the same – or even worse – conditions than those in Crimea. The author points out that it would useful for Crimea to adopt certain elements of Israeli water management, such as the large-scale use of wastewater for irrigation, as well as technological (i.e. genetic selection) and methodological innovations that increase the efficiency of agriculture, economical desalination plants, and innovations in water management policies. Effective drip irrigation and taking proper action against corruption in the implementation of water management programs would also help.

Water losses today in Crimea are monstrous, not only along the route of the NCC, which loses half of all the water that passes through it, but also in the municipal water sector. Yet there is also huge potential for water savings.

Mikhail Bolgov, a hydrologist at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Water Problems, said that 50-70 percent of already purified water supplied to consumers is lost in urban municipalities, particularly in sewer networks, which are in extremely poor condition and continue to degrade. In Simferopol the situation is especially acute: only 55% of the water supplied by the municipality reached the consumer in 2013, and by 2018 that figure had fallen to 43%.

In addition to a radical overhaul of the infrastructure, Bolgov recommends the development of instrumented systems for metering water consumption and discharge, combined with an increase in water tariffs and the issuing of fines for pollution. He also proposes reducing water consumption in industrial technologies and crop irrigation technologies, including through restructuring agricultural production.

Bolgov also recommended the artificial replenishment of groundwater during high-water periods (this will protect it from evaporation and allow it to be used during droughts).

Other experts and officials see potential for using the flow of groundwater into the sea, in particular in the Azov region, where a very rich freshwater (or slightly saline) aquifer is found under shallow sea waters near the Arabat Spit. Some experts believe, however, that this will also draw saltwater into underground aquifers.

The expert opinions presented in this article show that there are many well-tested opportunities for improving water use in Crimea, the first of which is reducing water loss.

If current needs with losses and ineffective management amount to 240 million cubic meters per year, then if losses are halved (from 50 to 25%), less than 180 million cubic meters of water will be required. This is half the most conservative estimate of the volume of guaranteed water resources on the peninsula and less than 20% of the generally accepted estimate of the annual volume of these resources.

One thing is certain: the peninsula’s current water requirements will no longer be entirely relevant after the war, since the military industry is one of the biggest consumers of water in Crimea. Since 2014, the large-scale militarization of Crimea has led to hyperconsumption of water. Now, with a full-scale invasion underway, military water supplies have increased even more, as militarization has led to a colossal increase in the need for fresh water to service military personnel and equipment.

The question of what kind of agriculture will Crimea need after its liberation remains unresolved. It is highly unlikely that the restored Soviet agricultural system will be at all profitable once the billions invested in restoring water supplies and modernizing destroyed networks are factored into the equation. Moreover, irrigated rice cultivation is not Crimea’s first economic priority. In the best-case scenario, tourism will remain the basis of the peninsula’s economy and the most important branch of agriculture will be Crimean winemaking. In the worst-case scenario, the peninsula will be a smoldering hotbed of ongoing conflict with a cluster of military bases and very limited economic activity.

In the event that Ukraine manages to successfully liberate Crimea and join the European Union, there are good reasons to expect that the climate crisis, EU laws, and common sense will encourage Ukrainian farmers to develop effective agricultural production adapted to the climate of the dry steppes on a scale commensurate with the needs of the economy. If irrigated crops are grown then drip irrigation should be used. It is likely that livestock farming (common here before the Soviet “transformation of nature”) will have an increased role to play in Crimea, as it will throughout the south of Ukraine. In this case, Crimea’s future will be stable, albeit rather dry (which is not a problem). Above all, the future must be peaceful.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image source: epravda.com.ua