Alexei Ovchinnikov

Sanctions on the export of Russian fossil fuels can be effective only if they are enforced alongside energy transition policy. As long as the demand for hydrocarbons remains steady, then “gray areas” allowing countries to continue importing fuel from Russia will always be found. Ten years of sanctions against Russia for its aggression in Ukraine show this very clearly.

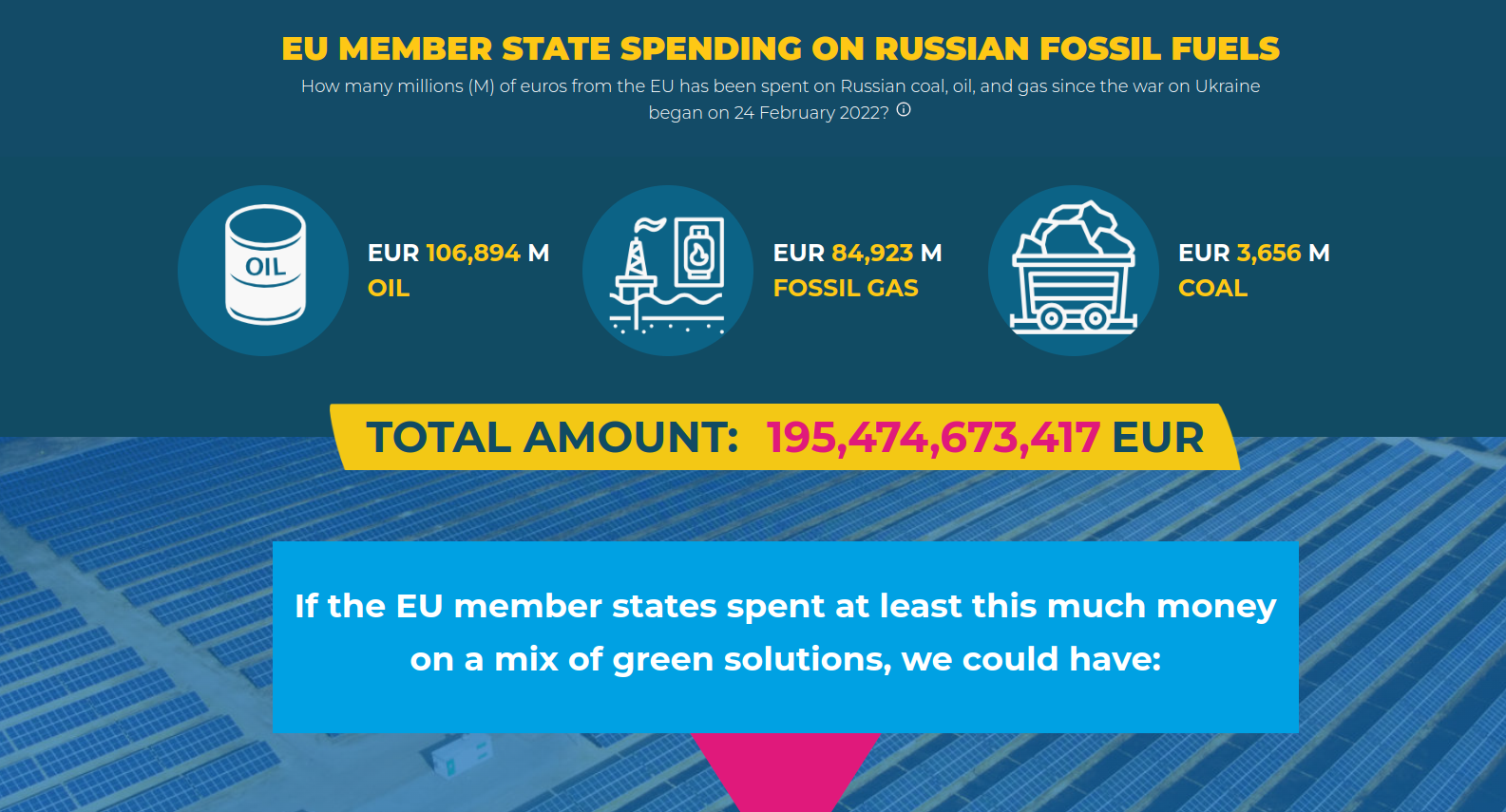

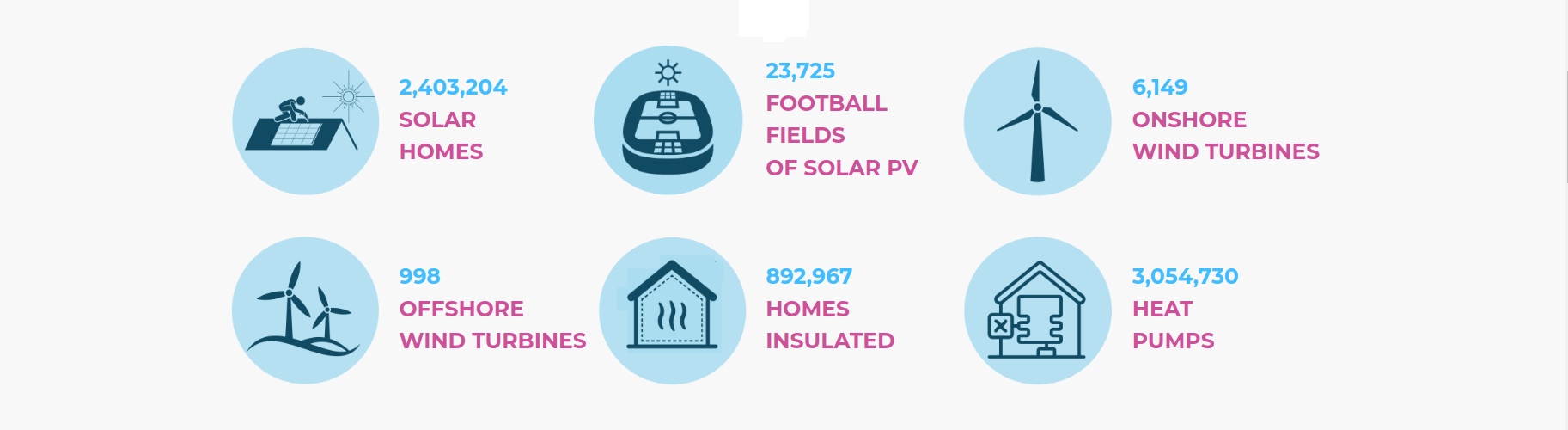

The Beyond Fossil Fuel initiative has launched a project to estimate the amount sum European Union (EU) countries have spent on the purchase of Russian fossil fuels since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. In the two and a half years of full-scale war since February 24, 2022, this sum has reached astronomical volumes. By 1 June 2024 it stood at almost 195.5 billion euros – enough money to fit 2.5 million homes with solar panels, build more than 6,000 land-based wind turbines and almost 1,000 sea-based ones, and supply more than 3 million homes with heat pumps. The aim of the project is to show that all of this money could have been used toward achieving carbon-neutrality and energy security instead of wasted on fossil fuel and filling the coffers of the aggressor. What’s more, that concerns only official imports – parallel imports via non-sanctioned countries and companies increase Russia’s earnings from the sale of carbon fuel several times over.

A brief overview of sanctions against Russia

The sanctions date to late 2013, when demonstrators took to Kyiv’s central Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) after Ukraine’s then-president Yanukovich abruptly changed political course, backtracking on promises to develop closer economic ties with the European Union and moving towards closer integration with Russia. After peaceful protests were violently broken up by riot police on 30 December 2013, the unrest grew in intensity. eventually leading to a series of bloody confrontations between protesters and police, resulting in the deaths of over 100 protesters. The uprising quickly became referred to as Euromaidan or the Revolution of Dignity.

From 18-20 February 2014, the escalating violence peaked, with armed encounters regularly taking place between protesters and police, and unknown snipers firing on those assembled on the Maidan. As a result, the police and interior ministry troops were forced to retreat. On 21 February 2014, Yanukovich fled Kyiv, and the day after the Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada (parliament) passed a motion stripping him of his post as president. It was during these days that Russia began to transfer troops to Crimea (officially approved by Putin on 1 March 1) to “support” those calling for the peninsula to secede from Ukraine. Essentially this represented the beginning of Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine. From April 2014 to February 2015, fighting raged across the Donbas, and in February 2022 the whole of Ukraine became a combat zone. Putin repeatedly declared that he did not recognize several regions of the country as part of Ukraine, including Odesa, Kharkiv, Kherson, Donetsk and Luhansk, labeling them as part of Novorossiya, the name historically used in Russia for imperial territory captured from the Ottomans and Cossacks in the 18th century.

The first EU and United States sanctions appeared in summer 2014. In general they were rather restrained, and were aimed at limiting Russia’s economic growth and mainly concerned specific companies and officials. A number of sanctions also targeted the export of fossil fuels from Russia, primarily oil. Yet these measures had no substantial effect on markets. In fact, right up until 2023 Russia remained the chief exporter of fossil fuels to the EU.

The full-scale invasion of February 2022 prompted a new reaction from Ukraine’s EU allies, the US, Japan, and other countries such as Canada and Australia, who not only offered support to Ukraine in its struggle to preserve its independence, but also ramped up Russia’s economic isolation, imposing sanctions not only on particular companies and individuals, but on entire sectors of the aggressor’s industry. One of the key areas was restrictions on the sale of carbon fuel.

On 8 March 2022 the US imposed a ban on the import of Russian oil, gas, and other energy resources. A month later, on 6 April, Britain announced plans to end any dependence on Russian coal and oil by the end of the year, as well as stopping the import of Russian gas as soon as possible. And on 3 June the EU adopted a package of sanctions that imposed a ban on the import of crude oil and several other oil-based products. In an attempt to make trade in fossil resources unprofitable for Moscow in November 2022, G7 nations agreed to cap the price of Russian oil at $60 a barrel. In January 2023 the EU tightened its sanctions against Russian carbon fuels while concurrently making efforts to ramp up development of the RePowerEU program, aimed at achieving greater energy independence and sustainability by 2024. On 5 February 2023 an EU ban on the purchase of Russian gasoline, diesel, and other oil-based products came into force.

Yet a full ban on Ukraine’s allies trading fossil fuels with Russia was not actually introduced, and Moscow relatively quickly reoriented its exports to other potential markets, betting on countries with rapidly developing economies, such as China, India, South Africa, and Brazil.

How effective have sanctions against Russia been?

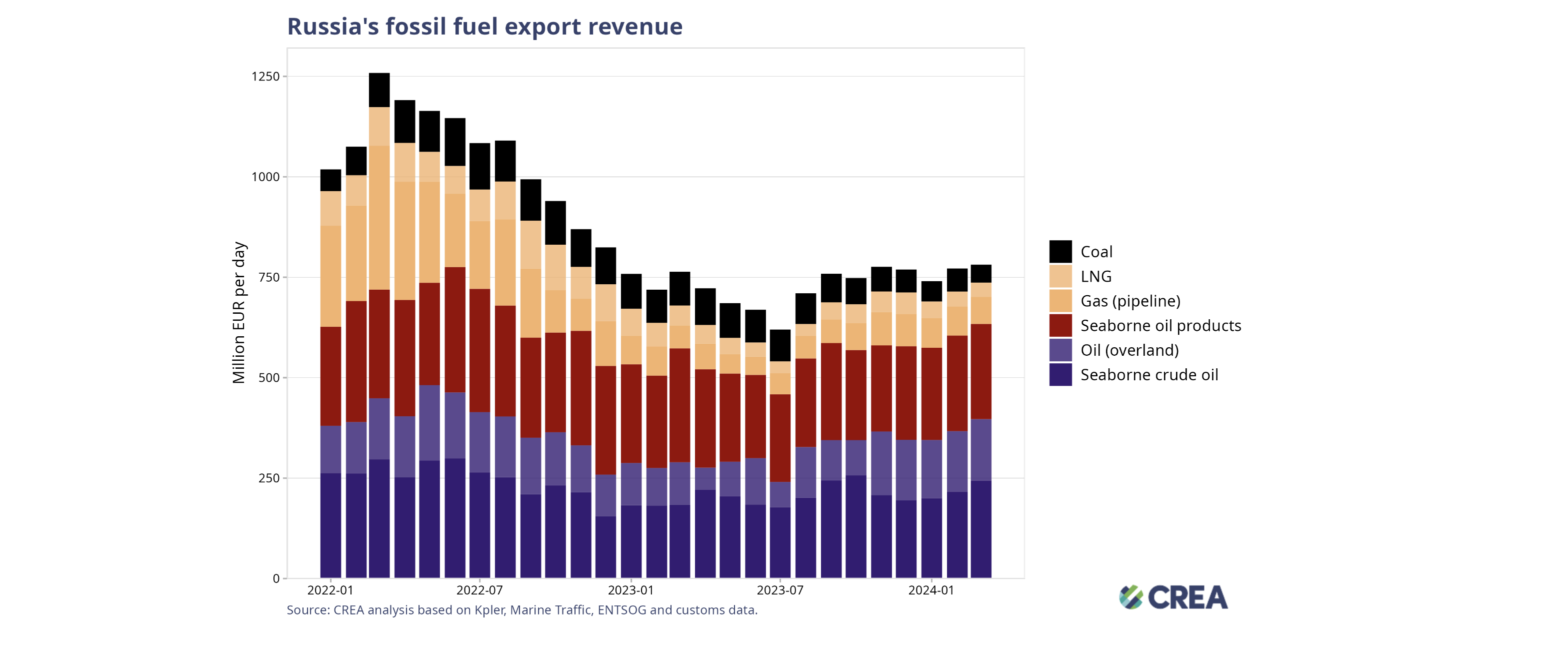

In analyzing statistics on the export of Russian carbon fuel, the Russian economy seems to have coped with sanctions, and this year it even began to claw back its losses. According to the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air, in March 2024 the total volume of Russian fossil fuel sales grew by 1% (to 9.4 million euros/day). Meanwhile, revenue from the sale of crude oil compared to the previous month increased by 9%, while income from marine transport of oil was up 13%.

One reason that sanctions have turned out to be ineffective is the “soft” position of some countries in the coalition against Russia, as well as their lack of consistency. Dr. Ulrich Schetter, a senior assistant professor from the University of Pavia in northern Italy, underscored this in May 2024 at a seminar discussing the effectiveness of sanctions, organized by the NGO Freundshaft kennt keine Grenze.

The European Union has chosen a strategy for its sanctions policy that inflicts maximum damage with minimal losses. In its summary of the sanctions, the European Council describes the list of banned products as “...designed to maximize the negative impact of the sanctions on the Russian economy while limiting the consequences for EU businesses and citizens.”

This position means that sanctions should not run counter to the interests of EU members, which provides plenty of room for speculation as to which consequences of sanctions are acceptable, and which are not. For example, the Hungarian government vetoed new sanctions on Russian gas imports, claiming that such measures would have possible negative consequences. Moreover, the sanctions were deliberately delayed in order to “minimize the consequences.” This soft position, given the rise in prices for fossil fuels, allowed Russia to increase its export revenues and recalibrate its markets in the first year of the full-scale war as a direct result of the sanctions themselves.

Another concerning aspect of Western sanctions is the lack of a united front among coalition participants. As Schetter noted in his talk, referring to data from Global Trade Alert, most imports from Russia (total import volumes) are not subject to sanctions, while the ban on imports to both the EU and the US affects only 0.2% of Russian exports. Other cases concern either a ban for EU countries, but not for the US, or controlled exports.

It is worth noting that such inconsistency and a complex bureaucratic structure create space for gray zones when companies from non-sanctioned countries are used to sell Russian products and resources to European countries and the US.

Beating sanctions: how Belarusian timber reached Europe via Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan

How such gray areas work has been shown, for instance, in an investigation conducted by the Belarusian Investigation Center. Belarus came under EU and US sanctions back in 2020-2021, when the Lukashenko regime brutally suppressed large-scale pro-democracy protests and cemented its friendly relationship with the Putin regime, essentially turning the country into little more than a Russian satellite. It bears recalling that when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian troops also attacked from Belarusian territory.

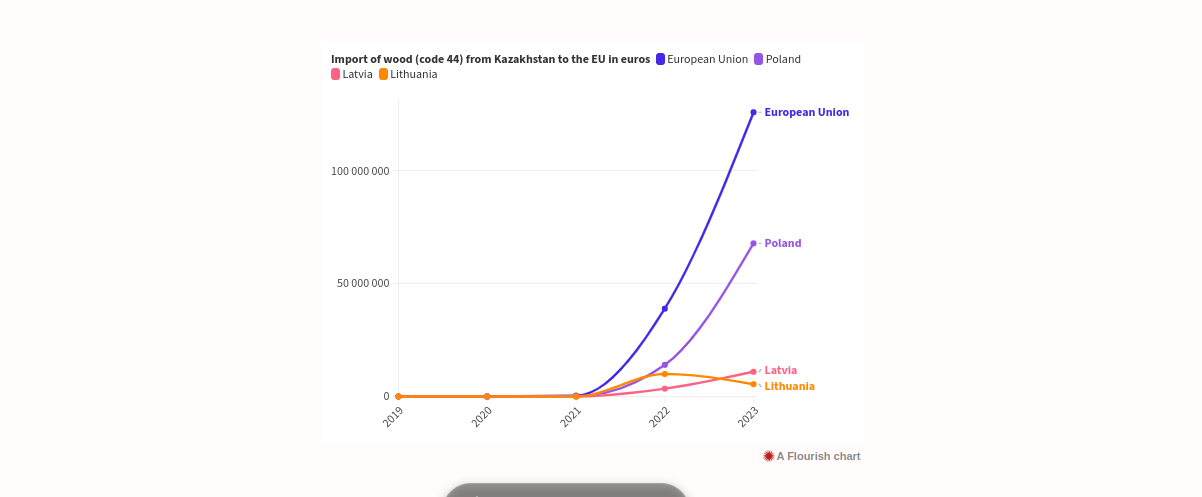

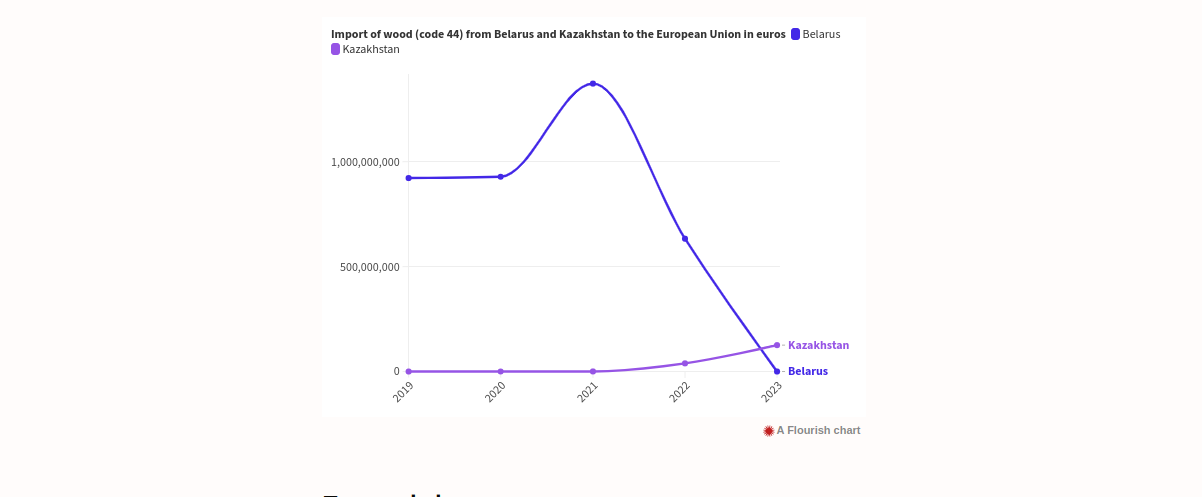

The investigation concerns the sale of forest products, primarily timber, through front companies registered in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Following the introduction of the expanded package of sanctions and the departure of international certifiers (such as the Forest Stewardship Council) from Belarus and Russia, timber exports from Kazakhstan reached record levels. Timber exports from Kazakhstan, which is not rich in forests, were previously negligible, while Belarus annually supplied Europe with 1 billion euros’ worth of timber.

Moreover, as the investigation reveals, in order for the timber to reach Poland, which has significantly increased imports of forest products, it was simply registered in Belarus as “Kazakh” or “Kyrgyz” and dispatched for sale. The scheme turned out to be so perfect that it continues to operate to this day.

This is not the first example of the Belarusian regime circumventing export restrictions on its timber. In 2022 Earthsight published an investigation showing how the EU had bought products manufactured in Belarus by political prisoners, with the proceeds used to support Lukashenko’s regime.

Similar “gray zones” also exist in the fossil resources trade. The complexity of the bureaucratic mechanism involved in applying sanctions, coupled with a reluctance to reduce resource consumption, creates opportunities for exports that circumvent those sanctions, taking resource exports into the shadows. In the context of the shuttering of environmental organizations, the extraction and trade of resources loses transparency. This all has negative consequences for nature.

This issue concerns not only Belarus and Russia, but also the countries where the Putin regime is trying to extend its geopolitical influence, such as Kyrgyzstan and Georgia. Both nations passed controversial laws on “foreign agents” and environmental organizations are coming under increasing pressure, and Kyrgyzstan has already announced its intention to lift restrictions on uranium production and plans to build a nuclear power plant under the auspices of Rosatom, the Russian state nuclear agency.

Environmental organizations against Russian fossil fuels

One of the first initiatives was an open appeal titled “Stand with Ukraine. End global fossil fuel addiction that feeds Putin’s war machine”. It was signed by more than 870 organizations from 57 countries, including two environmental organizations from Belarus that were closed down in the country and whose staff are now working in exile, as well as one organization from Russia. The purpose of the appeal was to draw the attention of world governments to the problem of importing carbon fuel from an aggressor, which is in contradiction not only with climate, but also humanitarian principles. Oil has become a symbol of the innocent blood spilled in Ukraine.

The most active work in developing sanctions on fossil fuels from Russia was and continues to be done by the Ukrainian initiative Razom We Stand. Also observing the connection between Ukraine’s partner-countries’ dependence on fossil fuels and the ineffectiveness of sanctions, the initiative’s participants published the “Manifesto for a New Ukraine and a New World” in the first half of 2024. Razom We Stand’s goal is to draw the attention of countries around the world, the European Union, G7, and G20 to the need for more radical changes. The manifesto demands five actions:

- Introduce a full package of energy sanctions against Russia;

- Invest in the development of a European continental energy network that would include Ukraine;

- End financing of the fossil fuel industry;

- Democratize (make more accessible) a just green transition;

- Reduce global dependence on oil and gas.

Not only NGOs, but anyone who is in solidarity with this position can sign the manifesto, which reflects both the interests of Ukraine and the entire world in the face of climate change threats and the growing influence of authoritarian “resource” states.

Environmental organizations are also calling for strengthened sanctions against Russian state-owned companies, such as Rosatom. Russia’s nuclear monopoly, which is directly involved in the occupation of Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant, continues to avoid direct sanctions pressure, a fact experts use to explain European Union and United States’ dependence on uranium supplies. It was not until December 2023 that the US Congress passed a law restricting the import of low-enriched uranium from Russia. Direct sanctions against Rosatom began to be discussed only in May 2024, when the United States prepared an equivalent bill. As for the EU, Europe cannot impose full-fledged sanctions, given that 15 of the 102 nuclear reactors in EU countries use Soviet systems to manage Soviet reactors that are specifically serviced by Rosatom. The solution, as Ihor Moshenets notes in Energy Post, is to replace these reactors in the near future with those operating on Western nuclear fuel and to increase autonomous fuel supplies from other countries. However, a number of environmental organizations believe that this plan is not only unsafe but also will not lead to energy independence. Kazakhstan, a suggested supplier of unenriched uranium, is also located in Russia’s geopolitical zone of influence.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has exposed Western nations’ dependence on resource-rich authoritarian regimes that continue to rely on the sale of fossil fuels and forest products to round out their budgets. The means to exit this system is to switch to more autonomous energy resources and achieve energy independence. In April 2024, carbon fuels accounted for less than a quarter of the EU’s energy mix for the first time, giving hope that such dependence can be overcome. However, achieving this will require not only and not so much development of a sanctions mechanism, but a reboot of the entire energy consumption system. Ukraine’s “green” recovery should be an important stage in this process.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image source: Japan Times