Alexej Ovchinnikov

Each month, the UWEC editorial team shares highlights of recent media coverage and analysis of the Ukraine war’s environmental consequences with our readers. As always, we welcome reader feedback, which you can leave by commenting on texts, writing to us (editor@uwecworkgroup.info) or contacting us via social networks.

New booklets reveal the environmental cost of the Kakhovka dam disaster

The Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group has published a two-part study devoted to the environmental consequences of the Kakhovka catastrophe and potential future scenarios. The first booklet is titled “Destruction of the Kakhovka Reservoir: Consequences for the Environment” and is devoted to an analysis of the damage caused by the blowing up of the dam at the Kakhovka hydropower plant. The second booklet, called “The Great Meadow vs.the Kakhovka Reservoir: A Modern Perspective,” analyzes two options for the future development of the region: the preservation of the forest that has sprung up on the bed of the former water body and the restoration of the river ecosystem, or restoring the reservoir. Several members of the UWEC Work Group took part in the project: Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Eugene Simonov and Valeria Kolodezhna.

The dam of the hydropower station was blown up, allegedly by Russian troops, on June 6, 2023. Within just 14 days, the Kakhovka Reservoir had completely vanished. The sudden release of water had a catastrophic impact on the ecosystems of both the lower Dnipro and the Black Sea, as well as nearby regions in southern Ukraine. Researchers distinguish three zones, each of which has its own type of environmental consequences: the former reservoir bed, the flooded areas and the northwestern part of the Black Sea. On the reservoir bed, for example, benthic (bottom-dwelling) organisms vanished and isolated bodies of water formed, becoming traps for fish, which died off en masse. This caused secondary water pollution. Ecosystems in the northwestern Black Sea have suffered from changes in salinity levels, eutrophication (“blooming”) caused by the influx of large volumes of organic matter, and the spread of blue-green algae.

The booklet pays special attention to the impact of the environmental disaster on nature conservation areas. As the authors explain, around 80% of the areas affected by the draining of the Kakhovka Reservoir have protected status at international or national level, and some are part of Europe’s Emerald Network of areas of special ecological interest.

The booklet also gives cause for cautious optimism. A year and a half after the disaster, nature is demonstrating its capacity for self-recovery. Local species—willows, poplars, and herbaceous species typical of these areas—have begun to grow on the bottom of the former Kakhovka Reservoir. Migratory fish species have also begun to appear in the Dnipro, and new ecosystems have formed in the drained areas.

The booklet is available online. Read “Destruction of the Kakhovka Reservoir: Consequences for the Environment” in Ukrainian.

Read more:

- The toxic legacy of the Kakhovka Reservoir

- Pollution from the bed of the Kakhovka Reservoir could affect water quality in local settlements

The second booklet, “The Great Meadow vs.the Kakhovka Reservoir: A Modern Perspective,” discusses the prospects for the region’s development. There are several options on the table at present — restoring the Kakhovka Reservoir or adaptation of the region to changes, taking into account the preservation of the newly formed Velykyi Luh (Great Meadow) ecosystem on the bed of the reservoir. The issue is quite complex, since the region’s infrastructure, created back in Soviet times, was closely connected to the reservoir. For this reason, the disappearance of the artificial reservoir had a negative impact on local communities (hromady). The greatest problem is the lack of water, which is extremely important for this agricultural region.

On the other hand, the young forests of Velykyi Luh that have sprung up on the bottom of the Kakhovka Reservoir will play a useful role in helping to better adapt to and mitigate climate change, which is having a serious impact on Ukraine’s southern regions. In addition, they can contribute to the conservation of water resources.

The authors of the booklet looked carefully at how the region around the Kakhovka Reservoir developed between the filling of the reservoir in 1956-58 and its destruction in 2023. They also considered a number of scenarios for the future of the region, of which there are two main options. The first is to allow the revival of the natural ecosystem of Velykyi Luh, which flourished here until it was destroyed when the cascade of hydropower plants was built on the Dnipro in the mid-20th century. It also envisages the use of modern solutions to provide the region with basic resources, primarily water. The second scenario involves returning to the Soviet past by refilling the Kakhovka Reservoir.

The booklet “The Great Meadow vs.the Kakhovka Reservoir: A Modern Perspective” is available online in Ukrainian and English.

Read more:

- After the deluge: Life on the banks of the Kakhovka Reservoir now the water is gone

- Rebuilding the Kakhovka Dam is a mistake, but what should be done instead?

- After the deluge: One year on, can the ecosystems disrupted by the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam recover?

Three years of war: what are the consequences for the climate?

Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, and over the past three years the war has had significant environmental and climatic impacts that will be felt for decades to come. Detailed studies are likely to appear after the war is over, but it is already possible to draw preliminary conclusions.

To mark the three-year anniversary of the war, the Ukrainian environmental organization Ecodiya joined forces with the Ukrainian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection, as well as the Initiative on GHG Accounting of the War, to carry out and publish research on the main consequences of the Russian invasion for the climate. The study shows the negative environmental consequences of the war not only for Ukraine, but for the entire planet.

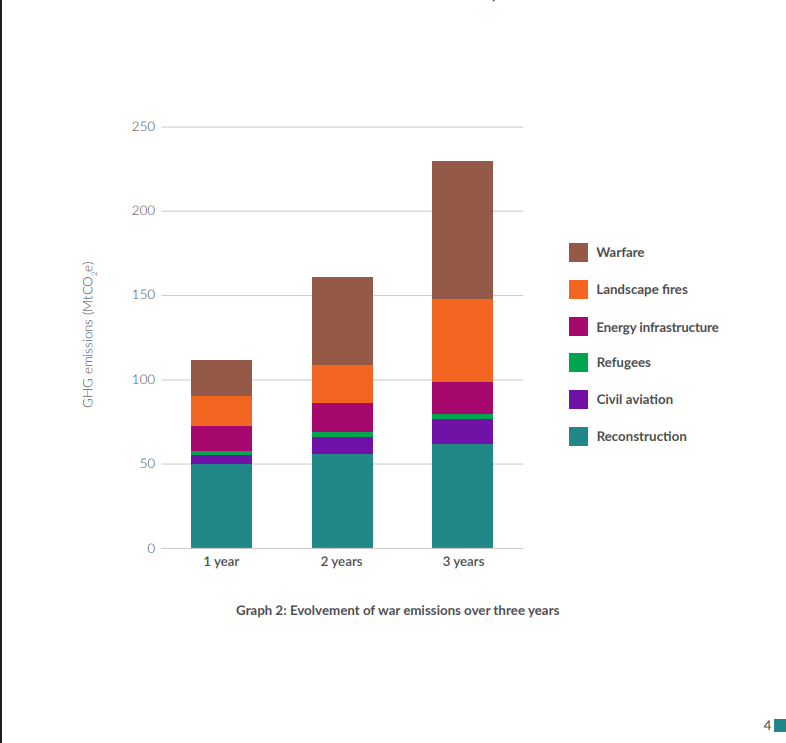

The study focused on 2024, which has turned out to be perhaps one of the most negative in terms of “unforeseen consequences” such as greenhouse gas emissions. It reports that greenhouse gas emissions caused by military activity, the reconstruction of buildings, landscape fires, damage to energy infrastructure, the movement of refugees and civil aviation increased in the third year of the war by another 30% or by 55 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2), bringing total greenhouse gas emissions to 230 MtCO2 since the start of the full-scale invasion. These figures are equivalent to the combined annual emissions of Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, or the total annual emissions of 120 million cars running on fossil fuel.

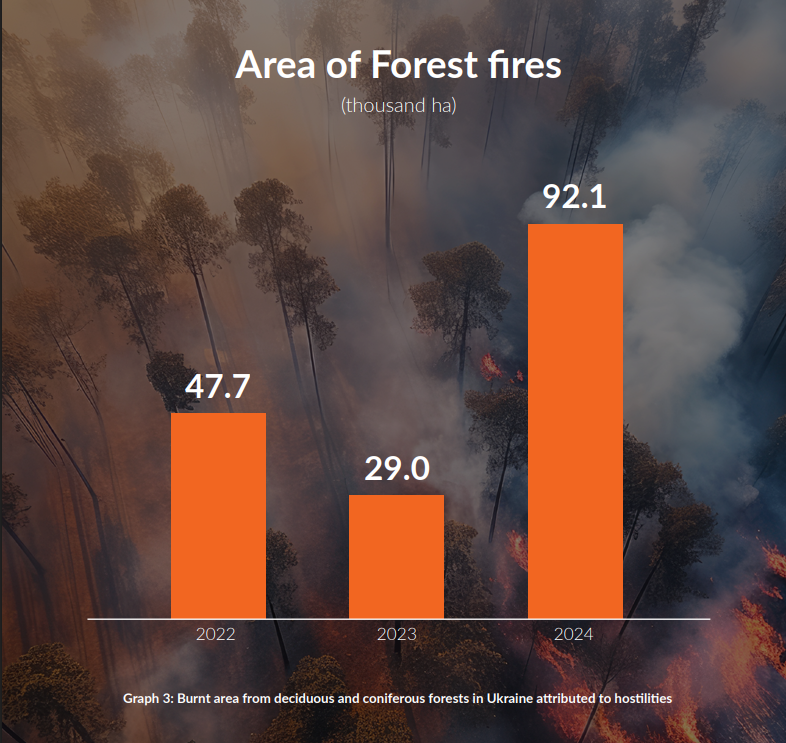

One negative trend is particularly noteworthy: an increase in the number of fires caused by military action in Ukraine in 2024. According to Ecodiya, in the last year of war, 92,000 hectares of land were burned.

Read more: Flames of war: How Ukraine lost over 1,000 square kilometers of forest

Over the past year, the percentage of emissions caused by the use of military hardware has increased significantly, despite the active use of drones. In the first year of the war, emissions from the use of military equipment totaled 21.9 metric tons of carbon dioxide, increasing to 29.7 MtCO2 in the second year, and rising to 30.5 MtCO2 in the third. Emissions are primarily produced by the carbon fuel used by military hardware. In the first three years of the war, total emissions from the use of military equipment amounted to 82.1 MtCO2, of which 74 MtCO2 are emissions from fuel combustion. For comparison, emissions stemming from the restoration of buildings and infrastructure over the same three-year period amounted to 62.2 MtCO2. Experts describe this sector as “the delayed consequences of war,” since the main reconstruction and restoration efforts will begin only after the end of hostilities.

As environmentalists from Ecodiya report, Russia will have to pay at least $42 billion for the consequences of its invasion of Ukraine for the climate. This calculation is based on the so-called social cost of carbon (SCC), which is equal to $185 dollars per ton of CO2 equivalent. Emissions directly related to the war are estimated at 230 million tons of CO2 in just three years.

“Russia started the war and it must bear responsibility for these greenhouse gas emissions,” said Lennard de Klerk, the study’s lead author.

Greenpeace activists take to the Baltic Sea to protest Russia’s shadow fleet

Ukrainian environmental organizations are now trying to draw the attention of the global community to the environmental consequences of the invasion through other means besides research, seminars and conferences. Natalia Gozak, director of Greenpeace Ukraine, recently went to sea in the Baltic with a group of German, Polish, Swedish and Danish activists to draw attention to the danger of using a “shadow fleet” of aging and unregistered vessels to transport fuel exports, the activists wrote the word “RISK!” in large letters on the hull of the oil tanker “Prosperity.”

Read about the environmental dangers of using a shadow fleet in our investigation:

The export of carbon fuels in the three years of all-out war has remained one of the main sources of funding for Russian aggression. As the Ukrainian environmental organization Razom We Stand points out, in spite of sanctions, Russia has made 212 billion euros during the invasion from exporting fossil fuels to Europe. Razom We Stand calls on the EU to tighten up sanctions, namely to completely ban the import of Russian LNG (liquefied natural gas), eliminate the “shadow fleet” that Moscow is using to transport fossil fuels, and close all loopholes that allow it to launder the revenue received from sales of oil, gas and coal.

Greenpeace Ukraine has made a similar statement. On the third anniversary of the full-scale invasion, the organization called on EU countries to:

- Include the shadow fleet in the next sanctions package. The shadow fleet not only creates risks of oil spills and marine pollution, but also helps finance Russia’s military machine. Greenpeace Ukraine also demands sanctions on Russian liquefied gas;

- Impose sanctions against the Russian nuclear company Rosatom and halt all interactions with this “criminal group”;

- Ensure that the Zaporizhzhia NPP remains shut down. The IAEA should make every effort to free the nuclear power plant from Russian occupation;

- Invest in renewable energy in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government should promote the decentralization of the energy system, which should allow the country to become energy independent.

After the full-scale invasion, Russia was able to adapt to sanctions and find ways around them. It was helped in this by the fact that the sanctions were not ultimatums and left loopholes that could be exploited in order to bypass them. Trade in LNG (liquefied natural gas) with Europe is a good example: as a recent study by Greenpeace Unearthed showed, Russia has been shipping Siberian gas to Europe via the Northern Sea Route. The active development of this route is already a consequence of climate change and the melting of Arctic ice. And exploiting it to sell carbon fuel in order to finance military aggression is the height of cynicism.

New commissions to study the environmental impact of the war on nature reserves

One area that Ukrainian environmental organizations and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection continue to actively work on is gathering data on damage caused to the environment, as well as legal support for compensation claims on both a national and international level. With this in mind, special commissions have been created to analyze the consequences of military action on nature reserves. These bodies include representatives of state inspectorates, regional and district administrations, as well as employees of nature reserves.

The Ukrainian environmental organization Environment People Law (EPL) has conducted an analysis of the work done by these commissions. These bodies were set up in all regions except Zakarpattia, which has not suffered from the direct consequences of Russia’s military aggression. The commissions were created according to different principles: in some regions they will operate under the regional administrations (i.e. there will be one commission per region), while in others they will operate under district administrations (i.e. several commissions per region).

As of 2025, no cases of damage as a result of military action to nature reserves had yet been recorded in the Vinnytsia, Volyn, Ivano-Frankivsk, Zakarpattia, Kirovohrad, Lviv, Poltava, Rivne, Ternopil, Chernivtsi and Chernihiv regions. Cases were documented to a various extent in all other regions of Ukraine.

As can be seen from the work of the commissions, nature reserves in the western and northwestern regions were not affected by the military actions. For our part, we note that it is unexpected that the nature reserves of the Chernihiv region, which was occupied in the first months of the full-scale military invasion, were not affected.

EPL is now carrying out a more detailed analysis of work done by commissions on the consequences of the war for affected nature reserves. A study showed that the furthest nature reserve from the frontline to be affected was the Starokostiantynivskyi hydrological reserve, a cascade of ponds on the Ikva River in the Khmelnytsky region. Changes in water quality were detected after a missile: the pond became turbid and dark in color, leading to the death of many fish.

Protected areas in the Kyiv region have suffered significant harm. One example is the Zalissia National Park, part of which was occupied by Russian troops from March 8 to March 29, 2022. The commission was only able to carry out a partial inspection of the park, as many areas were mined or contaminated with fragments of explosive objects. The inspection revealed the extent of the damage caused by various kinds of activity, including fires resulting from artillery and rocket shells, the felling of trees and the construction of fortifications, the littering of land with fragments of ammunition and the destruction of nests and anthills.

In the Zhytomyr region, more than 2,100 hectares of forest in the Drevlianskyi Nature Reserve to the northwest of Kyiv have been lost to fire as a result of missile and bomb strikes. Unfortunately, it remains impossible to record and determine the extent of the damage caused to the reserve. This is due to the presence of landmines, as well as a ban imposed by the Defense Council of the Zhytomyr Region on visiting forests within 30 km of the national border with Belarus.

EPL admits that the analysis being done by the commissions can hardly be described as complete: it is often carried out only partially, for reasons of safety or military security. In the Odesa region, for example, it is forbidden by order of the Odesa Regional Military Administration for anybody except for military personnel to enter the Black Sea’s coastal security zone, which makes it impossible to conduct a survey of nature reserves in this area. For some reason, however, the commission was also unable to record the consequences of military action in nature conservation areas in other parts of the Odesa region. All of this shows that a comprehensive study of the impact of the war on nature reserves will need to be carried out after the cessation of hostilities—and it may take quite some time.

WWF Ukraine project aims to restore treelines in war-hit territories (Mykolaiv region)

The war may still be going on, but some projects for the green recovery of Ukraine are already underway. One example is the restoration of treelines, strips of woodland dividing fields that are extremely important for the country’s southeastern regions.

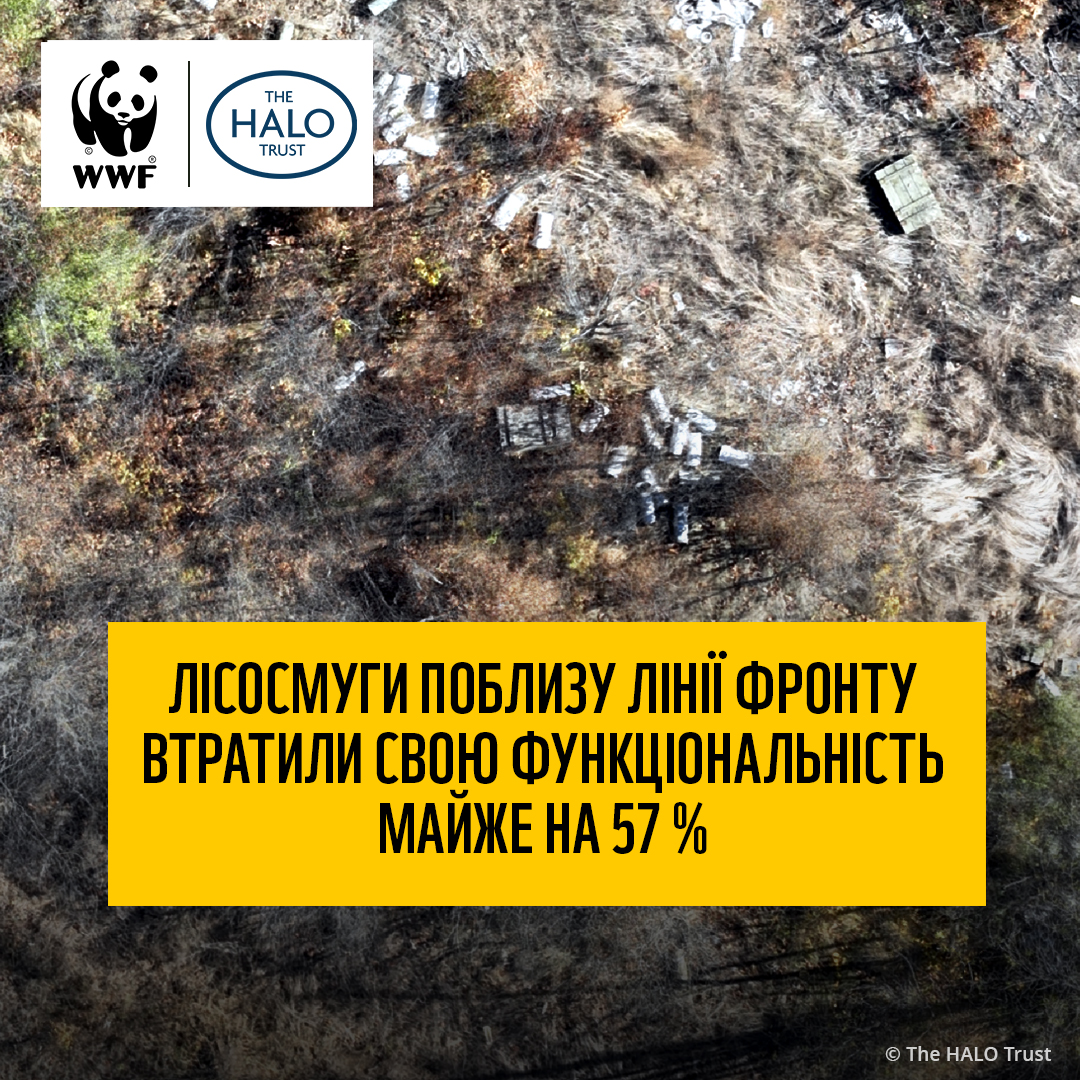

As studies show, 18% of treelines in the east of Ukraine have been damaged as a result of fires, shelling and the construction of fortifications, a figure that reaches 57% along the frontline. There is a high likelihood that this could lead to soil depletion, reduced crop yields, and contribute to desertification in areas significantly affected by climate change.

Up to 80% of these areas can potentially be restored using native species. However, this comes with certain risks, the most serious of which are the contamination of treelines with explosive objects, lack of funding, as well as the need for long-term care of new plantings.

WWF Ukraine has teamed up with The HALO Trust to launch a project aimed at restoring protective treelines in the Mykolaiv region. However, projects on a larger scale are needed, ideally with government support.

WWF Ukraine has also become a partner of the FarmForce international project, financed by the Swedish Institute. The aim of the project is to facilitate the development of agroforestry to help create sustainable food chains. It will support small farms in Ukraine by sharing experience with Swedish farmers, providing expert support, running workshops and raising public awareness of sustainable agroforestry practices. The initiative will allow Ukrainian agriculture to adapt to climate change, recover from the consequences of the war more quickly, and also provide the necessary support for small farms.

Environmentalists convene in Poland to discuss recovery plan for Baltic basin

Ukrainian environmental organizations met with the Clean Baltic coalition in Warsaw on 18 February to discuss a plan for the restoration of areas in Ukraine that form part of the Baltic basin. This primarily concerns the sub-basins of the Western Buh and the Sian River (a tributary of the Vistula). A number of actions are planned:

– Creating an information platform for the renaturalization of rivers called Living Rivers;

– Opening a branch of the “River University” in Ukraine, a training platform for the dissemination of innovations and practical experience in the ecological restoration of rivers;

– Revitalizing small rivers in the Lviv region;

– Taking an inventory of the buffer zones (water protection zones) of the Western Buh and Sian rivers, an assessment of their condition and the development of an action plan for their restoration;

– Restoring water-regulating treelines through cooperation with local communities and farmers, which will contribute to the conservation of ecosystems and sustainable use of land resources;

– Creating buffer zones in areas sensitive to pollution by nutrients, etc.

The Polish Ecological Club in Krakow and the Ukrainian organization EcoTerra are developing a plan for the green recovery of the areas of the Baltic basin damaged by Russia’s war in Ukraine, with the support of Coalition Clean Baltic and the Swedish Institute.

“Our focus primarily lies within the Baltic Sea Catchment Area of Ukraine and issues related to biodiversity, hazardous substances and eutrophication. Environmental problems originating in Ukraine affect the whole Baltic Sea Region and, therefore, require joint efforts to solve them.”

This project once again demonstrates that the environmental and climatic consequences of military intervention are transboundary in nature and also have an impact on countries in which military operations are not taking place.

Main image: Activists paint the word “RISK” on the hull of the tanker “Prosperity,” which belongs to the Russian shadow fleet. Source: Greenpeace Ukraine