Alexei Ovchinnikov

Each month, the UWEC editorial team shares highlights of recent media coverage and analysis of the Ukraine war’s environmental consequences with our readers. As always, we welcome reader feedback, which you can leave by commenting on texts, writing to us (editor@uwecworkgroup.info), or contacting us via social networks.

The main event in this past June was the anniversary of the explosion of the Kakhovka hydropower plant (HPP) dam, an event which led to both the depletion of the reservoir and an environmental and humanitarian catastrophe in the Dnipro River delta. Over the past month, several conferences, events, and studies focused on the terrorist attack on Kakhovka HPP, analyzing its main environmental consequences. Other discussions also focused on important recent occurrences, including conservation of the forests now growing on the bed of the former reservoir, an area historically known as Velyky Luh (“Great Meadow”) and ecocide taking place in Ukraine.

What is going on the bed of the former Kakhovka Reservoir? Conference outcomes

The “Kakhovka Reservoir Disaster: Tomorrow, One Year After and Future Prospects” conference took place 6-7 June 2024 at the Biology, Geography, and Ecology Department at Kherson State University. During the gathering, Oleksandr Khodosovtsev presented the work of an expert group that is monitoring vegetation restoration on the lands of the drained Kakhovka Reservoir.

He noted that one of the group’s focus areas is collecting data to bring the perpetrators of the dam’s sabotage to justice in accordance with Article 441 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “On Ecocide”. The group, which includes experts from a number of Ukrainian research institutes and NGOs. The NGO Environment.Law.People worked with participants to develop and present seven criteria for a legal definition of the term “ecocide”. One defining criterion is an action that leads to the destruction of a biotope – defined as an area with uniform environment and wildlife – and, as a result, 50% or greater of the country’s residents cannot benefit from environmental services. Experts believe that the sabotage of the Kakhovka HPP dam meets this criterion for an act of ecocide.

Oleksandr Khodosovtsev described how the monitoring group began its work on 30 June 2023, just weeks after the disaster. In total, the team organized four expeditions to the bottom of Kakhovka Reservoir over the better part of one year. Two small, flat-bottomed valleys in Kamianska Sich National Park were selected for monitoring.

The very first trip to Kakhovka revealed that the reservoir’s water level in the selected areas had fallen by 9.5 meters, a fact which greatly surprised the group members. The overall impression was shocking – a huge number of dead crustaceans, mollusks, and fish remained on the drying bottom of the reservoir.

Active natural restoration of vegetation began quite quickly in the zones selected for monitoring. By the second expedition, which took place on 19 August 2023, the emptied bottom of the reservoir had already been covered with several dozen plant species.

The scientists’ main concerns were that dust storms could arise at the bottom of the dried-up reservoir, as well as the possibility of invasive species overgrowing the land.

This rapid restoration of vegetation on the reservoir’s bed dispelled the fear that almost 200,000 hectares of newly-dry land would become a zone for the formation of dust storms. At first, the soil was covered in algae and aquatic plants, but then the ground began to be actively overgrown with other species. During the initial expeditions, approximately ten plant species were identified growing in damp cracks of the dried bottom.

The second concern was also unfounded. An expedition on 22 May 2024 to the north end of the former Kakhovka Reservoir showed that the bottom of the former reservoir was overgrown, mostly with willows. The tallest specimen that the researchers encountered stood 4.75 meters tall in an area with a density of 32 plants per square meter. In total, more than one hundred plant species were recorded during the expeditions, only a quarter of which were invasive species. Those species occupy only small areas, mainly in the sandy coastal zone. These same willow thickets block alien species from reaching the bottom itself, enabling the biotope to recover naturally.

Moreover, a year after the disaster, a storeyed vegetative structure began to form, a process that illustrates development of a stable ecosystem on the site of the former Kakhovka Reservoir. A layer of moss and lichen began to appear on the bottom.

Today, a forest typical for this part of Ukraine is being restored: poplars are actively growing over sandier, higher banks while willow thickets take over the bottom.

View speaker presentations from the conference (in Ukrainian):

Sabotage of the Kakhovka HPP dam: War crime

The international NGO Truth Hounds has been collecting data since 2014 on war crimes that took place during the conflict in Ukraine, as well as during military conflicts in the Caucasus and Central Asia. In June 2024, they released a report on the impact of the Kakhovka HPP disaster on ecosystems, the agricultural sector, and civilian infrastructure in Ukraine.

The report shows the history of the construction of the Kakhovka HPP, presents an investigation into possible terrorist attack scenarios, and analyzes the consequences of the dam’s sabotage.

As Truth Hounds noted, hydropower plants accounted for approximately 12 percent of the country’s electricity generation before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Researchers classify hydropower plants as renewable energy sources, with the country’s highest concentration of renewable energy sources located in the southeast, namely in the Dnipro, Zaporizhzhya, Kherson and Mykolaiv regions. These areas suffered the most in 2022-2023, another factor that contributed to the country’s falling renewable energy production.

The Dnipro River delta, where the Kakhovka HPP was located, is also a center of biodiversity in Ukraine. The country has lands protected by the Ramsar Convention and a large number of species listed in the Ukraine Red Book. Areas such as the Lesser and Greater Kuchugury (‘dunes’) or the Sem Mayakov (‘Seven Lighthouses’) Marsh are extremely important nesting areas for migratory birds, meaning the entire Dnipro delta is important for preserving the entire region’s biodiversity. The Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO heritage site, is also located here. After the dam’s sabotage and water release, all of these territories suffered significant damage.

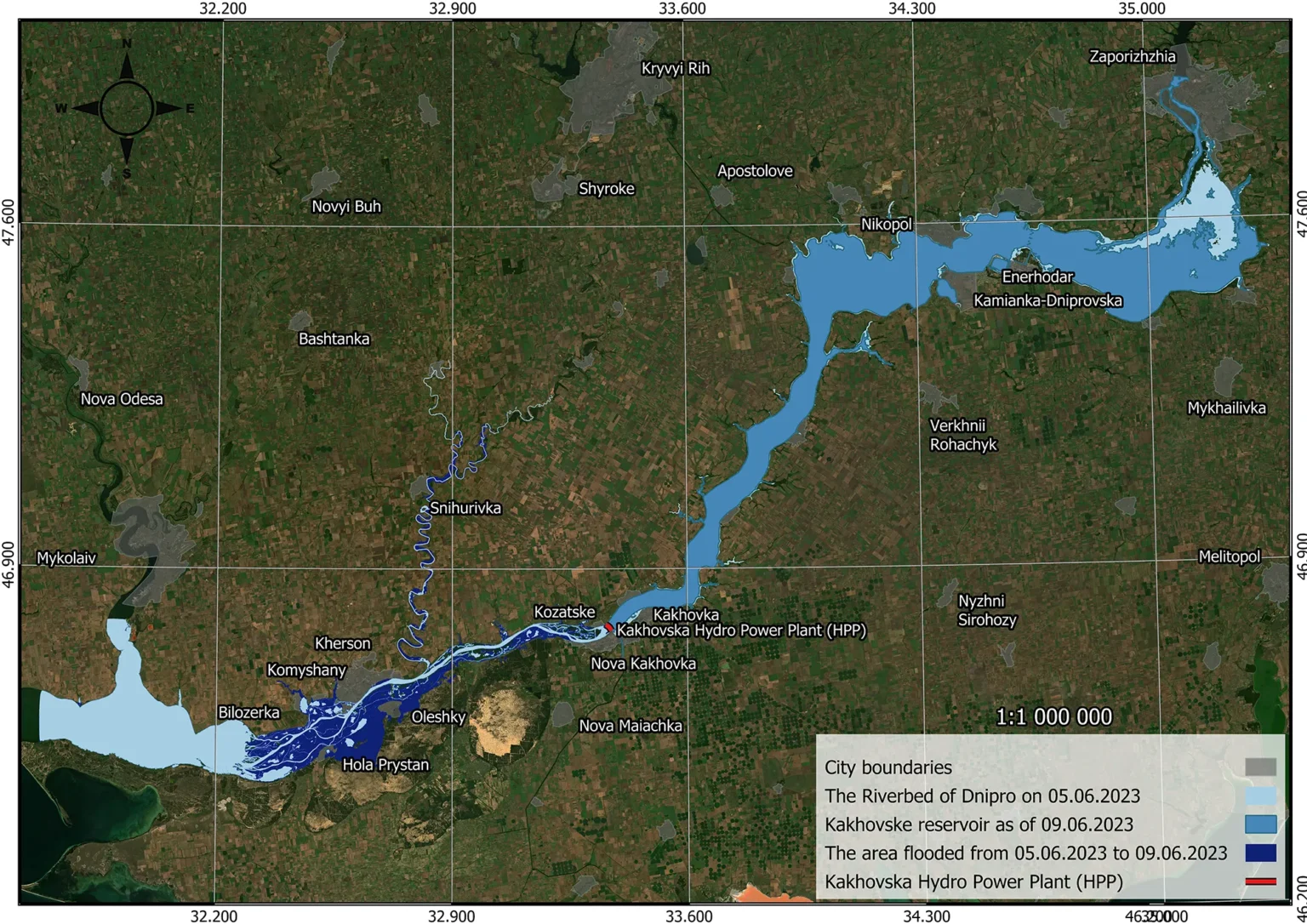

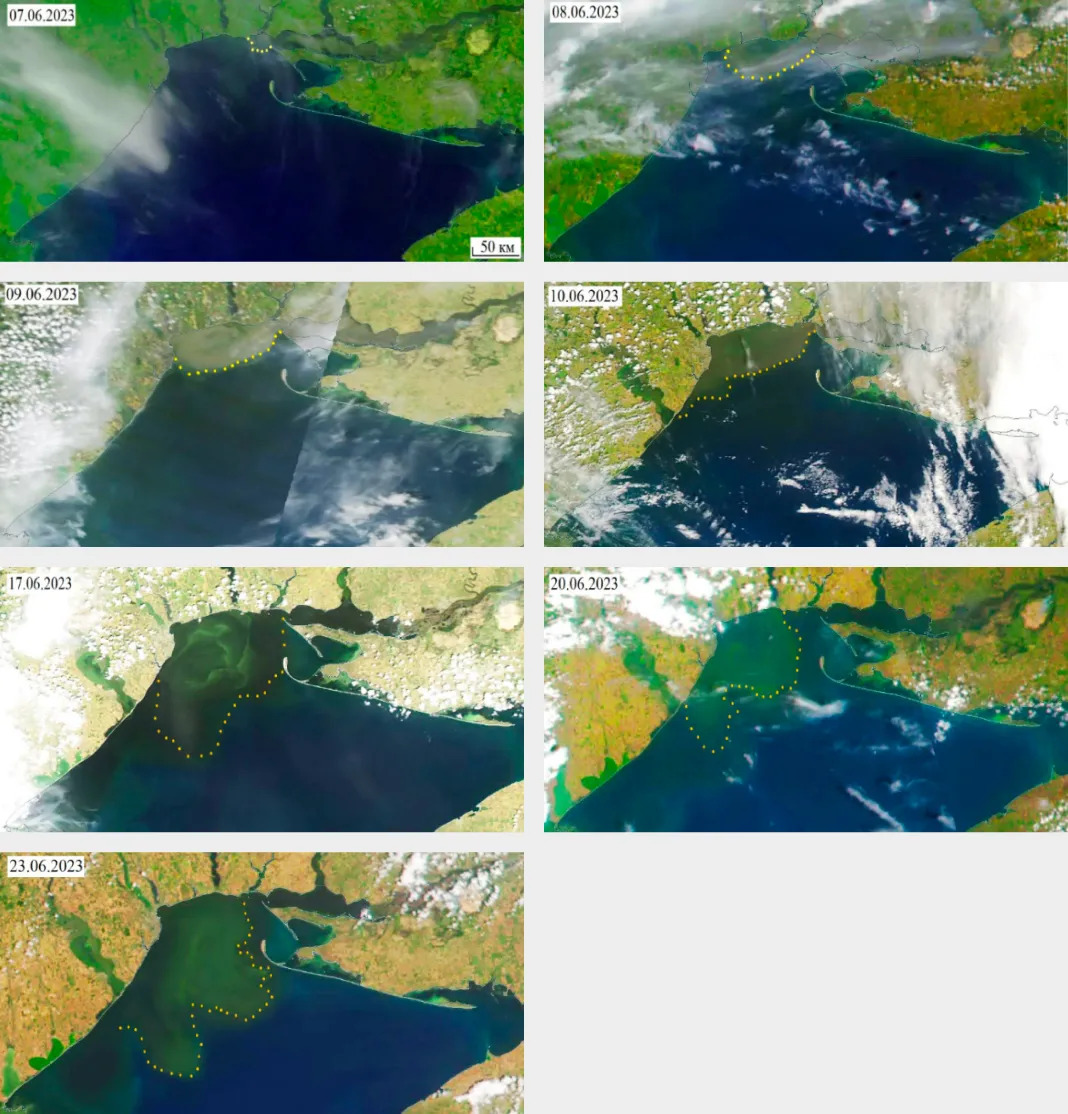

The main negative consequences were related to flooding immediately after the disaster. The floodwaters peaked on 9 June 2023, when Sentinel 2 satellite imagery showed that 1,284 sq km of land were covered by water in the delta. Before the disaster, on 5 June, this figure was just 812 sq km, meaning that 464 kilometers of previously dry land were flooded. By 5 July 2023, the water had receded to cover just 825 sq km, meaning that water levels actually reached the pre-rupture level, although the actual cartography of the upper waters and the basin, of course, changed.

Among the main environmental consequences of the dam’s destruction, Truth Hounds researchers noted a rise in groundwater levels, resulting in flooding of houses and areas located at some distance from the Dnipro delta itself. Overall, the reservoir’s release changed the groundwater regime in the delta. Studies conducted in September 2023 by the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine showed a critical drop of 5-7 meters in groundwater levels in the Kakhovka Reservoir area.

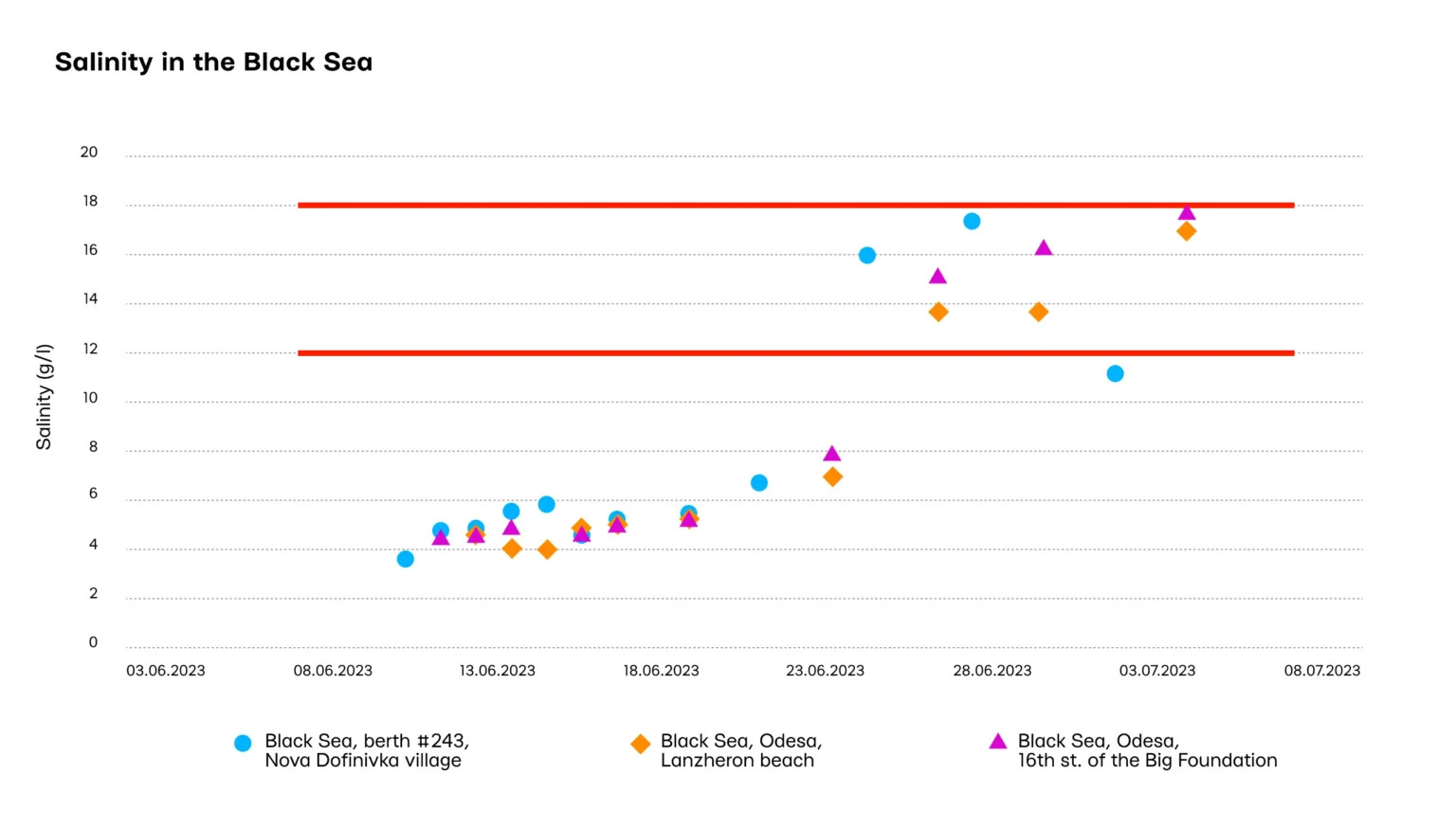

After the disaster, scientists worried about decreased salinity along the Black Sea coastline, a fact which could have a negative impact on local ichthyofauna. This did indeed happen in the first days after the disaster, but by the end of June 2023 salinity levels were restored as the waters mixed.

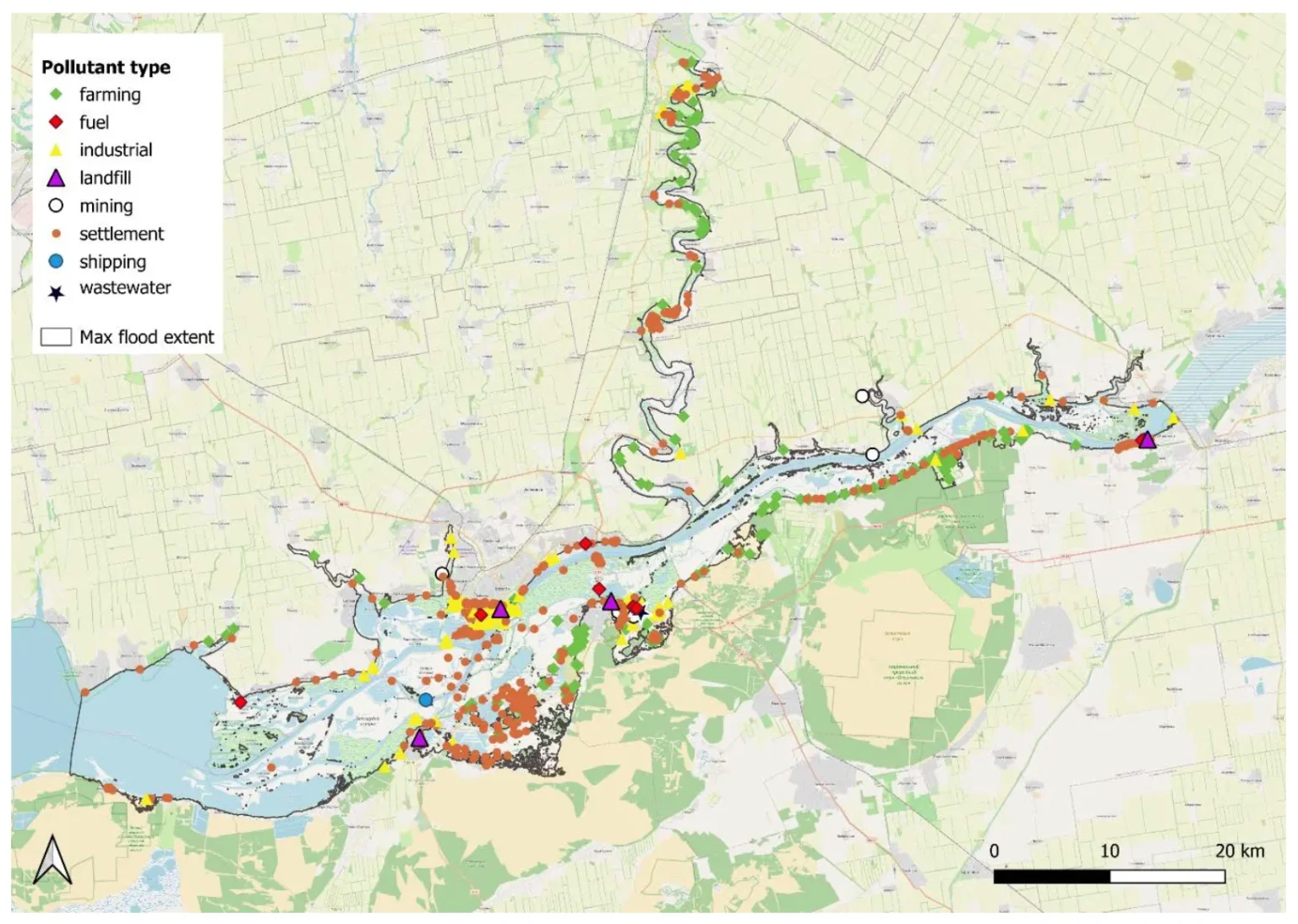

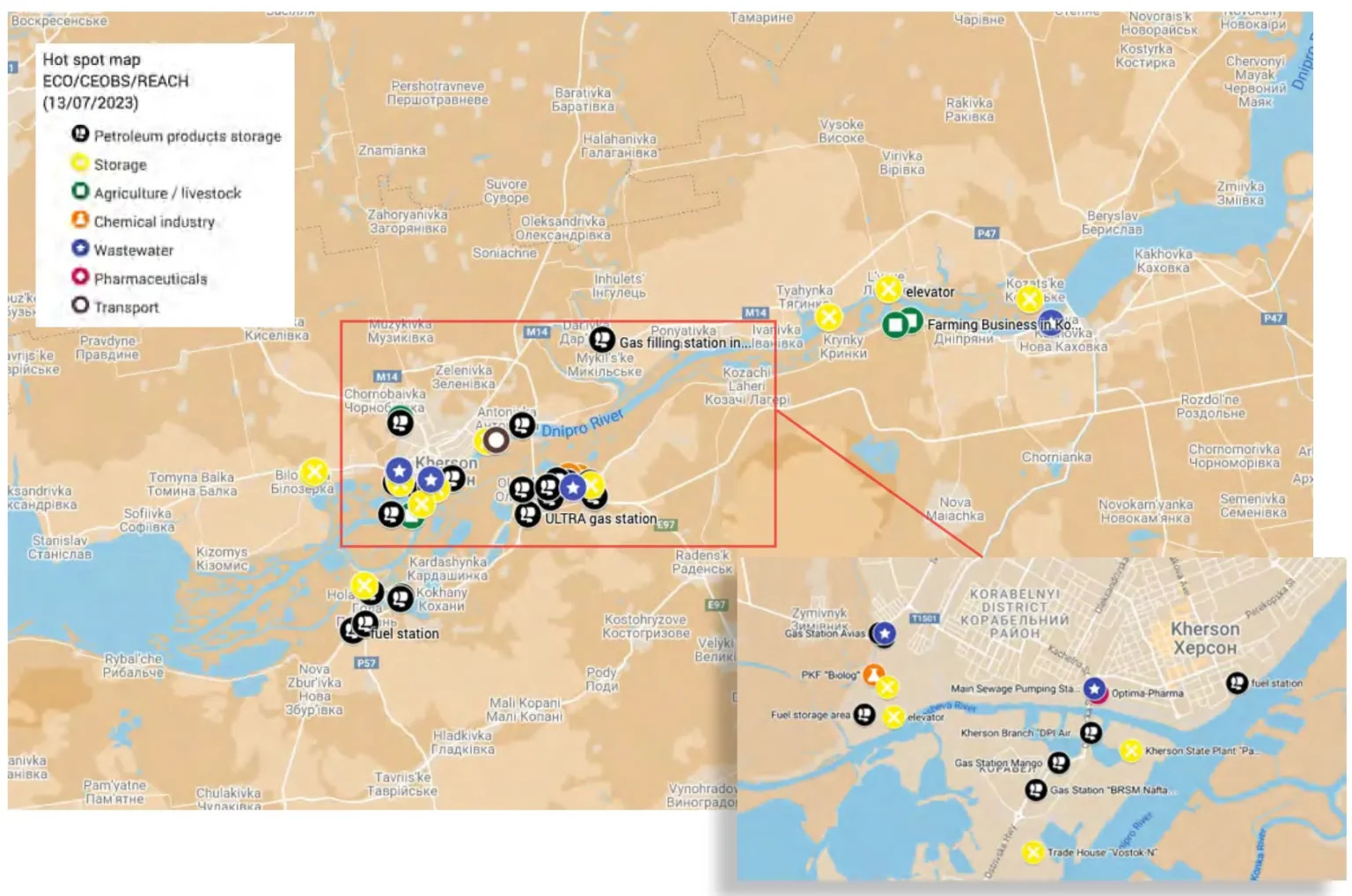

Another major concern was chemical pollution of waters in both the Dnipro delta and the Black Sea. The areas through which floodwaters passed were fairly dense metropolitan areas, meaning, for example, that sewage water would also have entered the river. The area also contained gas stations, farms, chemical industry facilities, and even pharmaceutical plants. For example, Greenpeace noted 32 fuel and agricultural industry facilities in the flood zone, all of which are potential pollution sources. The Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS) recorded 88 hazardous facilities, 49 in areas controlled by Ukraine and 38 on the Russian-occupied right bank. Ecodozor reported 194 potential pollution facilities.

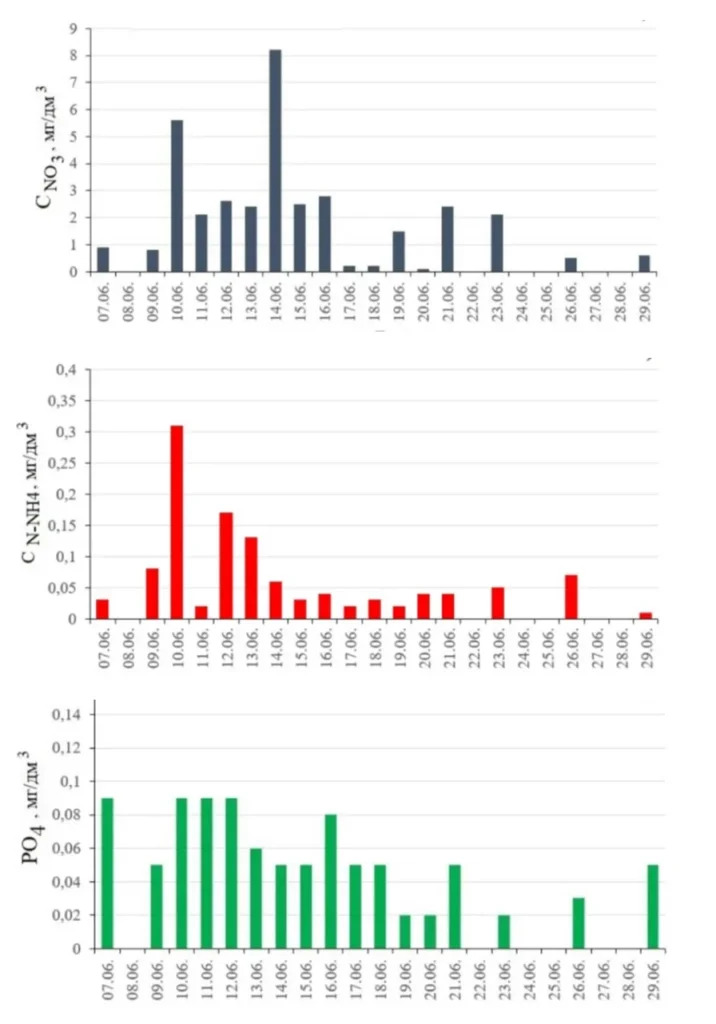

Analysis of water samples collected in the first days after the dam’s destruction along the Black Sea shoreline near Odesa showed significant increases in concentrations of oil products, toxic metals (zinc, cadmium, arsenic), and chloro-organic compounds. In July 2023, these concentrations declined and returned to normal, perhaps the same effect seen with the desalination of water and mixing in a large water area.

The story with organic pollutants and nitrates was similar. Samples showed a significant excess in concentration standards in the first days after the disaster, decreasing as time wore on.

It is obvious, however, that the toxic substances raised by the flood did not simply disappear, but rather are highly likely to enter groundwater. Between infrastructure destruction, pollution of land and groundwater, and the death of biotopes, this data can be taken as evidence of ecocide against Ukraine.

Researchers also worried about bacterial pollution of the Black Sea, which had received a significant amount of organic matter. Indeed, satellite images showed an algal bloom in the waters that shifted precisely in accordance with circulating currents from east to west.

Lastly, pollution stemming from military sites is of no little importance. Flooding of the Dnipro delta occurred at the same time as Ukraine’s counteroffensive in areas on the lower left bank of the Dnipro, an area occupied by Russian troops. As a result, both fortifications and minefields were flooded as well, resulting, of course, in significant volumes of military waste being dumped into the Black Sea. The danger of such pollution is that it can persist for many years and decades in the form of washed-out mines, flotsam munitions, and other dangerous military objects. This type of pollution can kill people and animals and continue to threaten nature even after military operations end.

Holding the aggressor state accountable for environmental crimes committed

The sabotage of the Kakhovka HPP dam is one of the main components of the Ukrainian government’s case for prosecuting a case of ecocide in order to hold the Russian government accountable and seek reparations. In accordance with an agreement developed by the High-level Working Group on the Environmental Consequences of the War in Ukraine, the Cabinet of Ministers created an action plan. However, environmental and nature conservation NGOs asserted that the process was tokenistic and proposed a number of changes.

The Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group proposed several noteworthy changes. The group’s experts propose using the concept of “Planetary Boundaries” as the plan’s basis. This concept asserts that the planet’s resources are limited and that all states must work together to reduce pollution and sustainably use existing opportunities to avoid harm to future generations. Furthermore, war crimes that inflict environmental pollution represent not just an attack on the country’s natural heritage but also a crime against humanity and planet Earth.

UNCG experts also provided detailed input on the wording of specific points in the plan. By the end of June 2024, Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers accepted the comments, remarks, and proposals, after which the plan will be finalized using input provided and shifting from there to plan implementation.

UWEC Work Group will continue to monitor implementation of the action plan and supports greater involvement of environmental organizations in all programs related to surmounting the war’s environmental consequences.

Dnipro River Integrated Vision

With the support of Ukraine’s State Agency for Water Resources, NGOs Greenpeace and Urban Coalition Ro3kvit, presented a proposed Dnipro River Integrated Vision in early July 2024. The initiative’s goal is to showcase the Dnipro River as Ukraine’s largest and, perhaps, most significant river, along with its historical, cultural, infrastructure, and environmental significance for the country as a whole, as well as the consequences of the full-scale invasion on the river.

From environmental and climatic perspectives, the Dnipro River is extremely important for the entire region. Flowing from its headwaters in Polesye in the very north of Ukraine, the river descends into the Black Sea, passing through a variety of biotopes including forest, forest-steppe, steppe, and semi-arid steppe. There are a large number of nature conservation areas on the river’s banks, including the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, Kamianska Sich National Park, Biloozerskyi National Park, Velyky Luh National Park, and the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. Many of these areas are either included in the Emerald Network for the conservation of European biodiversity or are protected by the Ramsar Convention.

During the Soviet era, the Dnipro River was heavily regulated, including the construction of six hydropower plants; a system of reservoirs was created with the goal of producing electricity and supporting agricultural and infrastructure functions. All of this infrastructure development resulted in the flooding of villages, historical sites, and entire biotopes. The river was also used to transport extracted minerals, industrial zones were formed on its banks, and the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant was built.

During this full-scale phase of the war, many cities and other sites located along the Dnipro River have been damaged. For example, the village of Gorenka, located near Bucha and only 15 kilometers from the Dnipro River, was almost completely destroyed. Today, Gorenka is being restored and, as the study’s authors noted, it has the potential to become a symbol of Ukraine’s “green transformation”. National parks and reserves located along the river have also suffered from the war as has Ukraine’s infrastructure, and recreational use of the river has ceased.

The Dnipro will certainly play an important role in Ukraine’s restoration. The country’s infrastructure is directly intertwined with this large river, and the future of not only Ukraine, but the entire region, depends on a sustainable recovery for the river rather than permitting a “business as usual” consumerist attitude to remain.

The Dnipro River Integrated Vision is available in English and in Ukrainian.

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Main image: Part of the river on the Kamianska Sich National Nature Park territory is covered with meadow plants. Source: Serhii Skoryk