Alexei Ovchinnikov

Each month, the UWEC editorial team shares highlights of recent media coverage and analysis of the Ukraine war’s environmental consequences with our readers. As always, we welcome reader feedback, which you can leave by commenting on texts, writing to us (editor@uwecworkgroup.info) or contacting us via social networks.

Fiber optic drones: a new source of pollution

Russia’s war in Ukraine has led to advances in military technologies, including drones. As with any technology aimed at destruction, advances in drone design have also led to new types of pollution. More and more videos and photos are appearing showing scenes that look like something from a science-fiction movie—fields or forests covered with a web of thin wires. This is the result of using drones guided by fiber optic cables.

Drones have become a key element of combat operations, not only performing reconnaissance tasks but also playing an active role in offensive actions. They can be used both on the frontline and deep in the rear, as Kyiv’s recent operation to destroy Russian strategic bombers in the Irkutsk region (Siberia) demonstrated so clearly. This all contributes to the development and modernization of this technology, making it deadlier and more effective—which also makes it more dangerous to the environment.

Meanwhile, methods are also being developed to combat drones, including electronic warfare (EW) systems. These work by jamming drones’ communication with operators or disabling the devices. Of course, this pushes developers to look for new solutions, one of which is fiber-optic EW drones. These avoid signal suppression and are fairly effective on the frontline. The signal is transmitted via a fiber-optic cable, which unspools behind the drone as it flies, making it more difficult to suppress. However, this type of drone can have catastrophic environmental consequences in the form of a “web” of wires.

As the Conflict and Environmental Observatory (CEOBS) notes in an article, Russia was the first country to actively use fiber optic drones. Ukraine quickly adapted the technology to its needs and today about 10% of drones produced in the country use optic fibers to operate. These drones use one of two types of fiber: glass optical fiber (GOF) or polymer optical fiber (POF). Polymer is more suitable for frontline conditions, being less fragile, more flexible and not as heavy as GOF. As the name suggests, the lines are made of synthetic polymers; a single drone can carry up to 20 km of line in a reel. At this level of technological development, reusing these cables is unrealistic and is complicated, among other things, by military action. Inevitably, then, frontline areas are now being polluted on a large scale with plastic waste. Optical fiber ends up in the ground as a result of fires, the movement of equipment or other actions, leading to both soil and groundwater becoming seriously contaminated with microplastics. For now there are no detailed studies on the decomposition of fiber optic lines used in new-generation drones, but preliminary analysis shows that they can stay in the ground for up to 600 years.

Stretched optical fiber also poses a threat to plants, animals and birds, which can become fatally entangled in it. When lines get wrapped around the limbs or neck, they often result in death and strangling. There are no comprehensive studies on this issue yet, since these types of drones have appeared on the battlefield only recently, and the war remains in an active phase, making field research impossible.

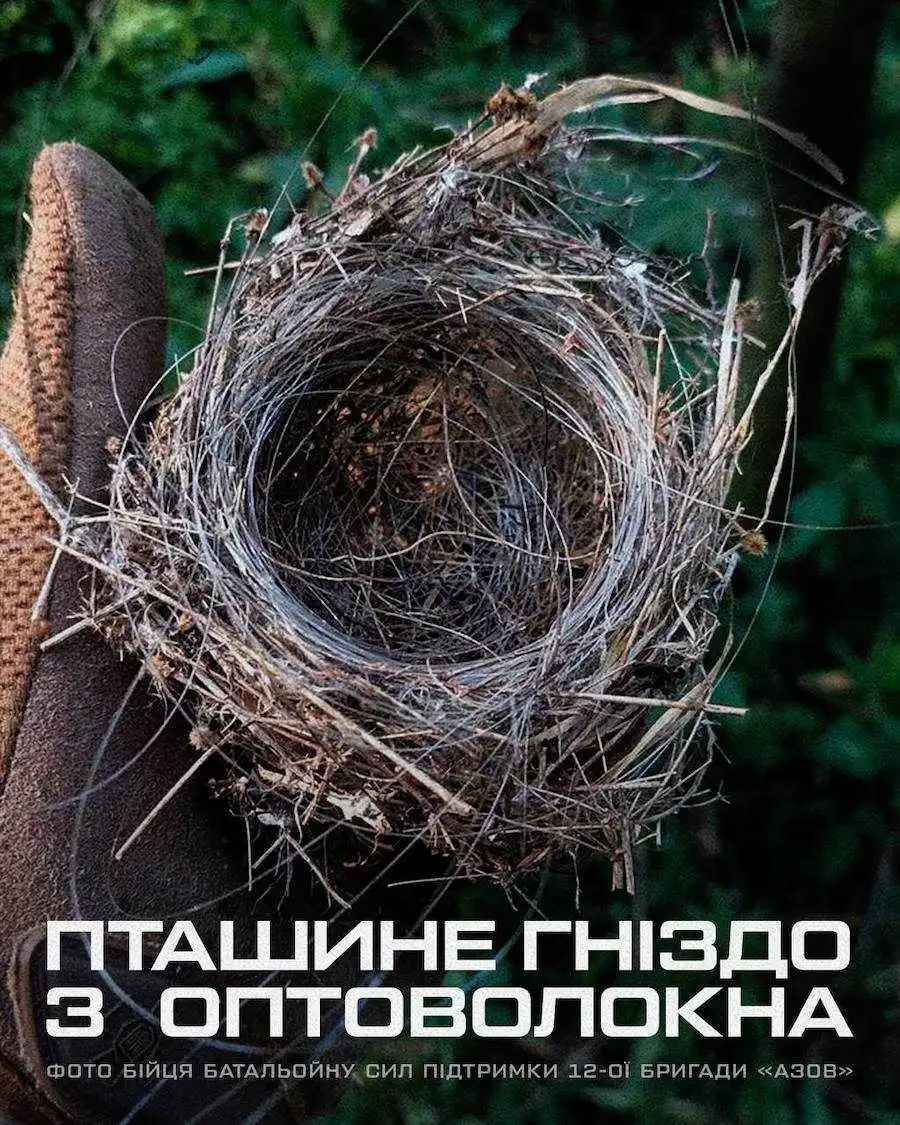

There have also been documented cases of nature trying to adapt to this new pollutant. For example, Ukrainian soldiers from the 12th Azov Brigade of the National Guard of Ukraine found a nest made partially from optic fibers.

There are plans to increase production of fiber-based drones or first-person-view (FPV) drones (FPV) in both Russia and Ukraine. Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, has adopted a law lifting taxes on the import of components for fiber-optic drones as a stimulus for production.

In view of the new threat to nature posed by military fiber optic pollution, UWEC experts have begun work on an article focusing on pollution as a result of the use of FPV drones. Keep an eye on our publications.

How can we protect the environment amid growing military conflicts?

There is a sense that humanity has entered a new phase of conflict, in which it is opposing its own interests. Whether in the form of hot wars or frozen conflicts, military confrontations are currently taking place all over the planet. At the same time, wars have an increasingly negative impact on the environment, which Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has clearly shown. A way to end the war has yet to be found, but discussion of what is perhaps the key modern problem (climate change aside) facing global society continues.

On May 14-15, 2025, the Center for Earth Ethics (CEE) ran a webinar titled “The Environmental Costs of War,” held in partnership with CEOBS, the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, and the Diocese of San Diego.

The first day of the event featured a panel discussion with four participants: Doug Weir (director of CEOBS), Dr. Christina Bagaglio Slentz (director of Care for Creation at the Life, Peace and Justice office in the Diocese of San Diego), Dr. Olena Melnyk (a research associate at the Bern University of Applied Sciences) and Elaine Donderer (a project manager at Israel’s Arava Institute).

On the second day, Weir was joined by Helen Obregón Gieseken, Legal Adviser to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Gilles Carbonnier, Academic Advisor to the Executive Course on Nature-Positive Economy, for an online discussion titled “Conflict and Nature: How to Protect the Environment?”

The meeting addressed the impact of armed conflict on the environment and the need for more effective law enforcement, data collection and multilateral governance in order to protect natural resources. The participants were unequivocal in their position that armed conflicts are inherently harmful to the environment, causing damage that is exacerbated by climate change and pollution crises. We are therefore facing a series of growing crises, and it is crucial to find solutions to them as soon as possible.

The environmental impacts of military conflicts and their consequences are an issue that is being increasingly recognized, especially in Ukraine. While legal frameworks for the protection of the environment in conflict situations exist (including international ones), their implementation remains insufficient. At the same time, there are liability mechanisms for damage caused to the environment during armed conflicts, based on international humanitarian law, which classifies such actions as war crimes.

Experts say that effective data collection and coordination are crucial for assessing environmental impacts in conflict zones, and multilateral governance involving international researchers and organizations can improve transparency and cooperation in natural resource management, both during and after conflicts. At the same time, it is worth considering the mechanisms for solving the problem on a larger scale—this could include economic practices on top of environmental ones. Diversifying the economy will allow the country to recover more quickly after the war and thus find the necessary resources to restore the environment.

Events like this, with their high level of expertise, show that interest in the topic remains. However, it is still unclear what exactly international organizations can do to protect the environment from human military conflicts. For now, while we frequently hear recommendations and proposals, there are no specific mechanisms for action on the horizon.

Ukraine plans to sign high seas treaty that Russia refuses to join

Russia refuses to sign an international treaty on marine diversity, a decision that may well be related to its interest in resource extraction in the Arctic. The Agreement on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, or the High Seas Treaty aims to establish an international mechanism for environmental protection in marine areas that are not under state control. Such areas are now growing in size in the Arctic, and Russia is keen to exploit their resources, refusing to recognize them as de jure international waters.

According to Natalya Hozak, director of Greenpeace Ukraine, Kyiv should sign the agreement in order to have a legal mechanism of influence over Russia and prevent Moscow from profiting from the extraction of new natural resources. It also demonstrates Ukraine’s interest in preserving the biodiversity of the world ocean, which is essentially the duty of any civilized society.

At the conference in Nice, Ukraine declared its support for the agreement. This was reported on social networks by Svitlana Hrynchuk, Ukraine’s minister of the environment. Greenpeace Ukraine highlighted the importance of this decision. “Even in the context of war and the fight for its own independence, Ukraine has demonstrated its commitment to European priorities and the global goals of sustainable development,” said Natalya Hozak.

It remains to implement these intentions. The agreement is open for signing until September 20, and the Ukrainian government has declared its intention to ratify by that deadline.

At present, the agreement has already been signed by 139 countries and ratified by 50. 60 countries must ratify the agreement for the agreement to enter into force. Ukraine’s voice in this matter is thus important. Readers can follow developments regarding the agreement’s adoption at a tracking website.

The agreement is de jure an instrument for managing the protection and sensible consumption of biodiversity in marine areas located outside national waters. Today, about 64% of the world’s oceans fall into this category. However, as the Arctic and Antarctic icecaps melt, such areas are only going to increase in size.

This agreement is also being described as a new legal document to combat three planetary crises: climate change, the loss of biodiversity and environmental pollution. The protection of neutral waters will create a legal instrument that should help to reduce negative impacts on the world’s oceans. After all, neutral waters, where national legal instruments have no force, are the most exposed and suffer from overexploitation. Illegal fishing can be carried out in these areas with relative impunity — according to the International Maritime Organization data, 26 million tons of fish are caught in these waters every year. International waters also suffer significantly from plastic pollution, as well as storms and hurricanes caused by climate change. In addition, they are vulnerable to being used for uncontrolled resource extraction, as we have noted in reference to the Arctic.

Russian missile attacks contribute to CO2 emissions and accelerate climate change

In an online speech to the OSCE Chairpersonship Conference on Climate and Security, held in Finland on June 11, Minister of Environment and Natural Resources of Ukraine Svitlana Hrynchuk drew attention to the environmental toll of Russia’s continued bombardments of Ukraine. Hrynchuk cited data on the “climate footprint” of the recent missile and drone attacks on Ukraine.

Odesa was subjected to 10 days of missile attacks in early June, resulting in the emission of 344 tons of harmful substances, while the large-scale bombardment of Kyiv in the evening of June 9 produced 1,902 tons of emissions. In three years of war, total emissions indicators have already exceeded 230 million tons of CO2. Just one year of military action in Ukraine produces CO2 emissions equal to those of a country like Belgium. And this ignores emissions associated with the manufacture of military equipment, logistics and other indicators—without even taking military action itself into account.

More than 8,000 cases of negative impact on the environment have been recorded during the full-scale Russian invasion, with the cost of the damage running at an estimated $94 billion. With every day the invasion goes on, the world is further delayed from achieving climate neutrality calling the green future of both Europe and the world as a whole into question.

Concluding her speech, Svitlana Hrynchuk warned that Ukraine cannot afford to wait for the end of hostilities to begin the task of environmental restoration. “The world is changing rapidly, but there is an urgent need for unity around environmental issues. Only together can we achieve our sustainable green future,” she said.

As the environmental NGO Covering Climate Now reports in its newsletter, recent studies show that military operations, including troop transportation, weapons testing, and the maintenance of military bases—of which the US alone has over 700 around the world—are one of the key sources of greenhouse gas emissions globally.

Excluding combat, military operations account for 5.5% of the world’s annual CO2 emissions. “If the world’s militaries were a country, this figure would represent the fourth largest national carbon footprint in the world – higher than Russia,” writes Nina Lakhani in The Guardian.

These figures are now being supplemented by the growing volumes of greenhouse gas emissions caused by fighting. A 2023 study found that the annual carbon footprint of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine amounted to 230 million tons, just under Spain’s annual emissions total of 270 million. And 15 months of Israeli military action in Gaza, as another study shows, have exceeded the combined emissions of 36 countries. Rebuilding destroyed homes in Gaza and Lebanon would produce emissions exceeding those of a country like Croatia. It is abundantly clear that wars are exacerbating the climate crisis. But by carrying out thorough analysis and publishing information, we can play an important part in bringing an end to wars, redistributing resources and beginning the path toward green recovery. If you are able, please do what you can to support the UWEC Work Group so that we can continue our work.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image source: euro-sd.com