While the world watches in horror as Russia’s war in Ukraine creates and exacerbates a food crisis, we also see how the threat of famine triggers decimation of natural ecosystems. Direct human consumption and agricultural production are two key factors driving declining biodiversity around the planet.

How the Russian invasion creates a global food crisis

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has reduced agricultural production and largely blocked Ukraine’s food exports. The international response to Putin’s offensive has also complicated exports from Russia and Belarus, with a bevy of international sanctions imposed on those nations’ banks, companies, and individuals.

Meanwhile, according to the “Global Report on Food Crises 2022” in 2021 Ukraine and Russia accounted for major shares of global exports of wheat (33%), barley (27%), maize (17%), sunflower seeds (24%), and sunflower oil (73%) (IFPRI, February 2022). The Russian Federation is the world’s top exporter of nitrogen fertilizers and the third largest exporter of phosphorus fertilizers (GRFC2022). Russia and Belarus alone control 40% of the world’s potash supply.

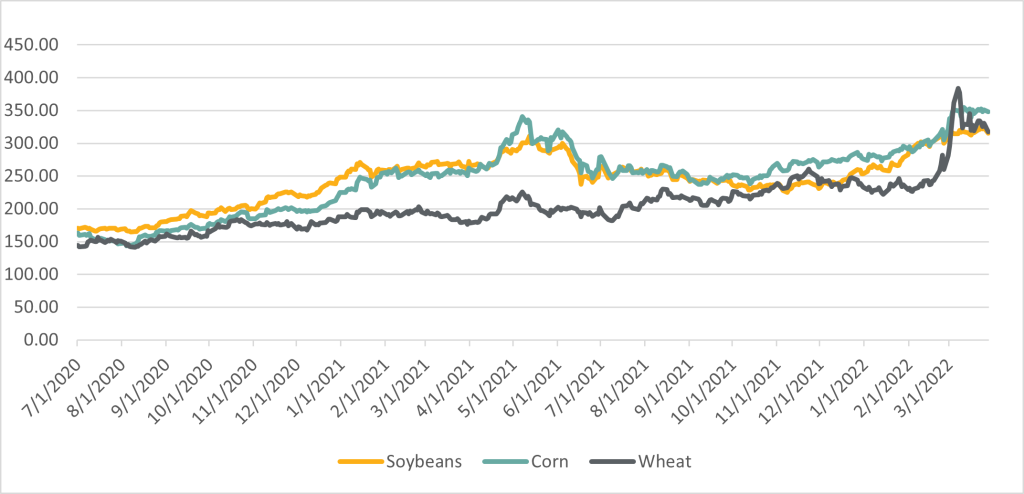

Reduced exports added to the problems caused by already soaring international food prices, prices which had reached an all-time high in late 2021. At that point, Russia imposed temporary limitations on exports of grain, plant oils, sugar, and some fertilizers, all of which contributed to the hike in prices.

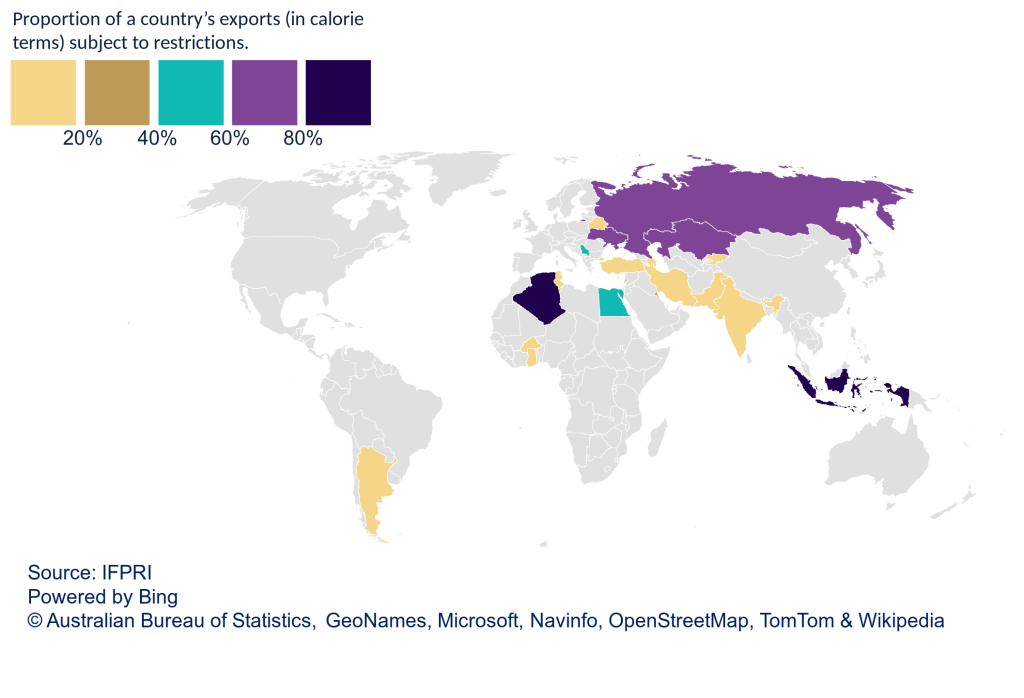

The global crisis deepened further as other exporter countries, including India and Indonesia, limited exports of wheat, plant oils, and other food commodities to protect their own population from price spikes and malnutrition.

In 2021, 36 out of the 53 countries and territories experiencing food insecurity around the world relied on Ukrainian and Russian exports for more than 10% of their total wheat imports, including 21 countries struggling with major food crises (e.g. Yemen, Sudan, Nigeria and Ethiopia).

For example, the East Africa region obtains 90% of its wheat imports from the Russian Federation (72%) and Ukraine (18%) (GRFC2022).

In May 2022, the UN’s World Food Program worried that declining food exports worsened by the Ukraine war would result in more undernourished people, as many as 8 to 13 million people in 2022 and 2023. That institution sources 50% of its wheat from Ukraine and Russia, helping to feed 125 million people worldwide.

How a global food crisis triggers environmental destruction

As countries strive to respond to war and food crises, their leaders often seek to relieve those pressures by encroaching on key biodiversity areas and the habitats upon which endangered species depend.

For example, in March 2022 the government of Ukraine simplified rules for the short-term lease of fallow agricultural land to allow food production by agricultural workers displaced from active war zones moving to other parts of the country.

According to Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group (UNCG), this move increases pressure on natural steppes and meadows – some of the most biodiverse and vulnerable ecosystems –severely damaged by indiscriminate expansion of arable land under the Soviet Union’s planned socialist economy. In May 2022, Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada legislature passed the law “On the peculiarities of land relations under martial law” (№ 2211-IX), which encourages resumed exploitation of natural meadows and steppes, even those located within protected areas. The new law contradicts several older pieces of legislation, but definitely aims to open non-agricultural land to plowing. Given that Ukraine has the capacity to produce 85 million metric tons of grain annually, most of it for exports, an extra 1-2 million tons of grain stemming from additional land development add little to the gross harvest and therefore do not contribute to Ukraine’s food security or economic prosperity. On the other side of this coin, development of the last remaining unplowed natural grasslands may lead to heavy losses in biodiversity terms.

Russia’s agriculture sector has been in the ascendant since long before its attack on Ukraine this year, boasting an all-time record grain harvest in 2021 and steady but modest annual expansions of plowed lands. Food commodities are excluded from western sanctions and arguably remain the most profitable export commodity upon which Russia can still rely. To fill the void in the grain market left by its own blockade of Ukraine, Russia is shooting for a record 85 million-ton grain yield in 2022.

As a result, reclamation of Russia’s arable land may proceed even more quickly this year. In April, President Putin sought to accelerate renewed use of cropland abandoned by Soviet-era collective farms, while the United Russia voting bloc in the Duma secured trillions of rubles in governmental funding for the reclamation of 13 million hectares over a 3-year period. As a result, arable land will grow by at least by 1 million hectares by the end of this year. In this process, remaining untouched natural grasslands may be targeted first thanks to the relative ease of their exploitation, while clearing newly reforested old fields requires greater investment.

A number of ecologists, all Russian and Ukrainian experts in grassland conservation, agree on the most likely negative consequences. Many species of birds, mammals, reptiles, and invertebrates that rely on natural grasslands will be displaced by reclamation of arable land in Ukraine and Russia. Steppe Eagle, Pallid Harrier, Red-footed Falcon, Little Bustard, Steppe Marmot, Speckled Ground Squirrel, Steppe Viper, and several species of Bush Crickets are species of special concern in western Russia, just to name a few examples. Restoration of the population of critically endangered Saiga Antelope in Russia’s Trans-Volga region will fail if even a fraction of the 900,000 hectares of presently fallow lands the species relies upon are converted back to crop production. Steppe-like grasslands on fallow lands are the only habitat type suitable for restoration of the steppe biome in Russia and Ukraine – tilling those lands renders biome restoration impossible.

Food as a weapon

Today, we are seeing the negative effects of a global crisis on environmental conservation programs all over the world. Several other grain-producing regions have attempted measures that may open high conservation value natural areas to agricultural development and mining.

On March 23 of this year, the European Commission held an extraordinary session to approve subsidies to farmers and allow member states to not only reclaim fallow land set aside to protect biodiversity, but also to treat those lands with pesticides. This attempted step backward for the EU’s Green Deal was led by France, which currently holds the EU presidency. An EU farmers’ union, Copa and Cogeca lobbied in opposition to the EU’s Farm to Fork policy as well, arguing that “Since the Russian government is using food security as a weapon, we must counter it with a food shield”.

Many environmental NGOs criticized the move and insisted that the Green Deal could be a cure, not an obstacle to food and energy security. Meanwhile, scientists argue that instead the EU should abolish the use of biofuels, the production of which consumes 9% of global crop production. The full extent of the damage from plowing “biodiversity lands” will be revealed at the end of 2022, as each country notifies the European Commission on the extent of its “derogation” plans. The cumulative negative impact may be substantial: Ireland has already indicated it plans to plant 25,000 ha of new cropland, while, according to its Ministry of Agriculture, Bulgaria will make full use of derogations and encourage farmers to use all available capacity for food and feed production. Just 5% of land in Bulgaria is set aside for ecological purposes.

The EU’s decision to sacrifice biodiversity for agriculture appears quite controv

ersial in light of Eurostat’s recent 2022 Sustainable Development in the EU report, which shows good to moderate progress on all UN SDGs (including those on energy and climate), but backslide for SDG 15, devoted to terrestrial biodiversity. Over the last 15 years, populations of common bird species declined by 5% and grassland butterflies plummeted 20%. The report clearly points to the key driver: “Agricultural intensification reduces natural nesting habitats such as hedges, wetlands, meadows, and fallow fields, while pesticides and changes in plowing times for cereals disrupt breeding and decrease available food sources.” Eurostat, likely anticipating negative effects from recently endorsed “derogations”, adds a disclaimer that “the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is not yet reflected in the 2022 SDG report.”

On the same day in March that the EU approved reclamation subsidies to farmers, seven lobbying organizations representing U.S. farmers and its food industry asked the US Department of Agriculture to allow planting crops on more than 4 million acres of “prime farmland” currently protected under the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Ironically, the 20 million-acre CRP is an environmental protection scheme set up 50 years ago when the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan resulted in a ban on US grain exports to the USSR at a time when many US farmers were overproducing. The CRP subsidizes long-term abandonment or restricted use of land susceptible to erosion, wetlands, and grasslands located on private farmland. The new planting proposal is still under consideration.

In early March, Brazil’s President Bolsonaro used the looming threat of fertilizer shortages stemming from the potential disruption of Russian and Belarusian exports as a pretext for reviving a draft law aiming to open Indigenous lands in Amazonia to mining. The law was first proposed in February 2020, but it was challenged in the courts and ruled unconstitutional. Bolsonaro claimed that mining in Amazonia will render Brazil self-sufficient in potassium and phosphorus fertilizers. A large scandal resulted when Brazil’s Socio-Environmental Institute revealed that only 1.6% of Brazil’s reserves of potassium and 0.4% of phosphorus are located on Indigenous lands. It was instantly clear, that this proposed legislation was actually aimed at gold mining and hydropower development on those same Indigenous lands. The proposal was again shelved after a major protest. In April and May, Brazil legally purchased a sufficient supply of fertilizers from Russia, as the transaction was not subject to Ukraine-related sanctions.

If high food prices and food shortages continue to exacerbate the situation in crisis-affected countries, it will necessarily have profound impacts on natural ecosystems and species. First, people will try to extract nutrients they no longer can buy at retail from the environment around them, resulting in widespread increases in subsistence hunting and adding pressure on flora and fauna. Secondly, families will expand inefficient but reliable subsistence agriculture to make up for food shortages. This sort of subsistence-focused encroachment took place in the outskirts of Russian cities during the breakup of the Soviet Union, when development of “collective gardens” led to the degradation of many high conservation value areas important for biodiversity, e.g. floodplain wetlands and peatbogs. As the crisis unfolds there are signs that similar expansion may be happening again today.

The cases examined here show that remaining natural areas, wild flora and fauna are being used to make up for food insecurity caused by the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia. Facilitated by governments, industry lobbyists use the crisis as an excuse to exploit natural areas with high biodiversity value, while malnourished populations resort to deriving food from surrounding landscapes by any means possible. These adaptations may severely compromise implementation of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals relating to biodiversity and biological resources.It is quite regrettable that in the 21st century, the largest food-producing nations in the world cannot identify better ways in which to confront war-related distortions in food trade beyond direct encroachment on natural areas. The war in Ukraine and its cascading impacts certainly provide ample opportunity for exploring creative new solutions.

Comments on “If not by sword then by plowshare: the ecological impacts of a war-induced food crisis”