Oleksii Vasyliuk, Eugene Simonov

In December 2025, Russia once again began to attack sunflower oil storage facilities, with Odesa the prime target. Some of this oil has ended up leaking into coastal waters. What are the environmental consequences of vegetable oil spills and how do cleanup methods differ from those used for crude oil?

On December 20–24, 2025, Russia carried out a series of destructive bombardments of Odesa and the surrounding region, damaging Ukraine’s largest sunflower oil terminal in the port of Pivdennyi. Thousands of tons of sunflower oil leaked from tanks owned by the company Allseeds into the Small Adzhalyk Estuary, where the port is located.

On Christmas Eve, the terminal at the Illichivsk Oil and Fat Plant in Chornomorsk was struck and damaged by drones and missiles. Two weeks later, on January 5, a factory belonging to the US company Bungе in the city of Dnipro was attacked. Three hundred tons of sunflower oil spilled onto the banks of the Dnipro River, and hundreds of tons of sand had to be dumped onto the puddles of oil to prevent it from entering the river.

It is no accident that Russia is targeting oil terminals and factories: Ukraine is the world’s biggest exporter of sunflower oil. In recent years Kyiv has exported 5–6 million tons of sunflower oil annually, making up 10–14% of Ukrainian exports (worth over $5 billion). Since the full-scale invasion, Russian forces have deliberately and purposefully bombed oil storage tanks in Ukrainian ports on numerous occasions in an attempt to undermine Ukraine’s economy.

While media headlines have traditionally been dominated by crude oil spills, environmentalists are increasingly sounding the alarm about so-called non-petroleum oils: palm oil, soybean oil, rapeseed oil, etc..

Previous large-scale vegetable oil spills in peacetime

Large spills of vegetable oil occur far less frequently than crude oil spills, but still happen regularly. The best-documented cases include the following:

– The spill of 10,000 tons of palm and coconut oil from the cargo ship Lindenbank, which ran aground on a coral reef off Fanning Island in the Pacific (Kiribati) in 1975. The subsequent mass die-off of fish and other organisms led to a long-term restructuring of the ecosystem.

– Several rapeseed oil spills (from 1 to 50 tons) in waters near Vancouver (Canada) in 1975–2018. Despite the moderate scale of these spills, they resulted in the death of a disproportionately large number of seabirds in comparison with crude oil spills in the same waters.

– In 1991, 1,500 tons of sunflower oil leaked from the vessel MV Kimya into the sea off the Welsh coast. Studies revealed the mass die-off of mussels and retarded reproduction.

– In April 2008, a palm-oil spill at a plant on the Colombian coast created a serious local environmental threat. Ten tons of oil leaked from the Terlica oil plant into the waters at Taganga, on the outskirts of the city of Santa Marta, leaving the bay covered with an alarming yellow-and-red slick. Local authorities rushed to reassure residents that “oil is a natural product and is not a pollutant.”

– In August 2017, a collision between ships in the Pearl River Estuary (Hong Kong) resulted in up to 9,000 tons of palm stearin (the hard fraction of palm oil) spilling into local waters. The oil formed white lumps resembling snow or polymeric foam, affecting 13 of Hong Kong’s popular beaches.

– In April 2020, 8.5 tons of palm oil (stearin) leaked from the ship Stavanger as a result of an accident in the Odesa region’s Pivdennyi seaport. Ukraine’s environmental inspectorate reported that the consequences were quickly neutralized, and a criminal case was opened against those held responsible.

Since vegetable oil spills are relatively rare, for a long time they were considered a minor problem in comparison to crude oil spills. It was only after 2000 that separate plans for the prevention and neutralization of vegetable oil spills started to be developed in the US (and later in Europe). But even these plans were not designed for spills resulting from military action and terrorist attacks.

These authors were unable to find any previous case in which a single large vegetable oil spill was caused by military activity or other international conflicts. The deliberate bombing of oil terminals, causing large-scale pollution of water and soil, is unquestionably a Russian military “innovation.”

Oil wars

The list of attacks on vegetable oil storage facilities in Ukraine is extensive, with both the Odesa and Mykolaiv regions suffering from repeated assaults.

– On October 16, 2022, storage tanks belonging to the company Every in Mykolaiv were struck and damaged by fragments from a kamikaze drone. Oil leaked from the tanks onto the street and into the waters of the Buh estuary via storm drains. In total, 676 cubic meters of pollutants were removed from the surface of the water.

– On December 28, 2024, a tank containing 1,800 tons of oil was hit by a missile and at least 25 tons ended up in the backwaters of the Southern Buh River estuary. Rescue services and employees of the affected enterprise spent three months dealing with the aftermath. Special floating booms were used to prevent the oil from spreading downstream and into the Black Sea. In total, over 120 tons of oil-water emulsion was collected. On March 21, 2025, the city council reported that it had used the sorbent Econadinl to absorb part of the oil. The rest had partly settled to the bottom and onto the banks of the estuary, or decomposed naturally.

– On April 19, 2024, a strike on a Singaporean agro-industrial enterprise in the port of Pivdennyi destroyed 10 tanks containing 10,000 tons of oil. Analysis of water samples in the Small Adzhalyk Estuary, where the port is located, showed the presence of fats and oils in a concentration of 136 mg/dm³.

– On October 9, 2024, after a missile attack in the port of Chornomorsk, port infrastructure facilities suffered severe damage, which resulted in over 125 tons of sunflower oil leaking into the Sukhyi Estuary.

– On October 9, 2025, Russian air attacks once again led to damage to the same facilities. As a result, large amounts of oil once again spilled into the Sukhyi Estuary.

In terms of volume and potential consequences, these spills are comparable with those that happened in the past elsewhere, but they had never occurred with such frequency in the same bodies of water. In addition, most previous large oil spills leaked from ships, rather than from coastal storage tanks.

As this shows, during this war capacities for the processing and export of vegetable oils have become a source of heightened environmental risk. This illustrates the need to develop a comprehensive response plan, primarily to prevent mass oil spills into water bodies and the spread of oil slicks across large areas of water.

How dangerous are vegetable oil spills?

An academic study of the consequences of spills in marine and freshwater bodies carried out in 2022 by Malaysian and Canadian scientists analyzes data on the effects of vegetable oil in aquatic environments, with an emphasis on oil biodegradation and toxic effects. In the majority of cases, these spills lead to the death of a number of organisms, as well as to changes in the dynamics of populations and the survival of more resistant organisms, which gain an advantage.

The consequences of vegetable oil spills are relatively short-term, since bacteria that decompose fatty acids quickly break down the spilled oil. Environmental conditions and the response measures used can limit the adverse impact of spills.

The lack of detailed research on vegetable oil spills and response methods creates a serious knowledge gap that the authors believe could be partially addressed through comparison with better-studied crude oil spills.

According to data from the US government agency NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), vegetable oils behave differently from petroleum products. While they do not evaporate, disperse (break up into small droplets) or dissolve like petroleum oils, the consequences for biota can be comparable in severity. On shorelines, they can polymerize, effectively enveloping objects.

Unlike petroleum products, vegetable oil is considered to be of low toxicity and does not cause instant chemical burns or long-term consequences such as cancer. Nonetheless, some intermediate products of oil breakdown are still toxic for marine life, and the practice of washing cargo ship holds at sea also threatens animals—in the UK, dogs have died after eating chunks of palm oil washed up on beaches. On January 1, 2021, this practice was banned when amendments to Annex II of MARPOL (the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships) for Northwest Europe came into force, requiring tanks and holds to be pre-washed in port and waste disposal to be carried out on shore rather than at sea.

As the 2024 fuel oil spill in the Kerch Strait showed, different types of petroleum products behave differently in water. Heavy fuel oil like mazut sticks together in patches and clumps, often sinking, while light fractions of oil create thin films on the surface. Liquid vegetable oil (sunflower, soybean, rapeseed oil, etc.) spreads across the surface far faster than crude oil and is much thinner, covering vast areas. It reduces the surface tension of the water, which can be fatal for neuston, a type of plankton that stays near the surface.

However, vegetable oil is excellent food for bacteria, which process it far more quickly and completely than petroleum products. The rapid biodegradation of liquid oil was partly responsible for the optimistic 20th-century view of it as a safe, “natural” pollutant. However, enormous amounts of oxygen are required for oil to degrade. This increase in BOD—biological oxygen demand—results in anoxia, a sharp drop in oxygen levels in the water, leading to the formation of localized oxygen starvation zones. When oil spills into bays, deltas and lagoons, it creates a film that blocks oxygen, killing fish even faster than crude oil spills. In vegetable oil spills, fish die not from toxins, but from suffocation and the physical clogging of their gills by the oil emulsion.

When oxidized, agitated and mixed with other substances and debris, oil can settle to the bottom. As it decomposes, it creates oxygen-free zones there, enveloping and killing bottom feeders. Mussels and other filter-feeding bivalve mollusks are one of the most vulnerable groups to these impacts. Environmentalists from Greenpeace Ukraine estimate that the potential negative effects from oil settling onto the seabed last up to six years.

Unlike petroleum spills, vegetable oil spills do not pose a serious threat to waterfowl (though there have been cases of birds pecking at solidified palm oil, resulting in diarrhea, dehydration and death). Just like petroleum products, vegetable oil kills birds physically by disrupting their thermoregulation. For a bird landing on water, there is little difference between fuel oil and sunflower oil: both substances disrupt feather structure and lead to death from cold. In addition, vegetable oil is extremely difficult to remove from feathers (unlike petroleum, which can be removed with solvents).

Vegetable oil spills are therefore highly hazardous to biota and marine ecosystems in general, but their negative impact is shorter than that of crude oil spills; the oils are broken down more quickly by microorganisms. However, the intense oxygen consumption that takes place during oil degradation means the negative impact can be significantly greater, especially in relatively enclosed bodies of water (lakes, bays and estuaries), where anoxic zones easily form.

Although in many respects vegetable oil spills are similar to crude oil spills, in developed countries there are special procedures for preventing them and cleaning them up when they do occur. For example, in 2000 the US adopted the Edible Oil Regulatory Reform Act, which separated approaches to petroleum oil and edible oils, but preserved the requirement to have a clean-up plan for spills. Companies that store large volumes of vegetable oil are obligated to develop a SPCC plan (Spill Prevention, Control and Countermeasure) and their activity is regulated by Federal Law 112 and the Facility Response Plan Rule. The SPCC requires that companies develop a three-tier system for protecting against spills. This includes operational procedures (instructions and automation) to prevent leaks from occurring, engineering controls (dams, double walls) that physically contain spilled liquid, and countermeasures (equipment and notification plans) that ensure rapid cleanup. These plans are developed at both enterprise and port complex level, with the primary objective of preventing significant volumes of oil from entering the water. This includes contracts with specialized services that can provide equipment and personnel trained to clean up oil spills.

Ukraine’s law “On high-risk facilities” (Art. 11) prescribes the development of an ERC (Emergency Response Plan) to deal with the consequences of accidents, including vegetable oil spills. However, there are no detailed requirements like those applied to plans for crude oil spills. The State Environmental Inspectorate reacts harshly to spills of vegetable oil in ports (there are many precedents in Mykolaiv and Chornomorsk). In order to minimize fines, companies (such as Kernel, Bunge Ukraine, Cofco) develop in-house response protocols for addressing vegetable oil spills. The Administration of Ukrainian Sea Ports is responsible for cleaning up oil spills in ports.

When time is of the essence

Although the spills in late December 2025 were far from the first attack to have targeted oil storage facilities, amid the repeated bombardments and confusion, Odesa’s emergency services were nonetheless too late in closing off the mouth of the Small Adzhalyk Estuary and the oil spread along the coastline of the Odesa region.

According to Oleh Hrib, the director of the Ukrainian Scientific Center of Ecology of the Sea, by December 24 the slick already stretched 55 kilometers along the shores of the Odesa region and covered almost 130 square kilometres. From December 24 onward, city residents frequently observed oily foam and large numbers of birds coated in oil, and subsequently avian corpses on the city beaches.

Local activists say Russia’s attack on the port of Pivdennyi bears the characteristics of a war crime and ecocide, as it violates the Geneva Conventions and the article on ecocide (Art. 441 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code). It is also a crime according to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. But the actions or inactions of officials of the Odesa regional administration may also be considered criminal, according to articles 236, 242 and 367 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code.

Read more: On the path to international recognition of ecocide

Vladyslav Balinskyy, an expert from the environmental organization Zelenyi List (Green Leaf), says that in the first days after the attack (December 20-21) there was still a genuine possibility of localizing the pollution within the confines of the Small Adzhalyk Estuary, where the port of Pivdennyi is located. This could have been done by closing off the narrow neck of the estuary using effective floating booms, as well as by actively removing the oil with special equipment for removing pollutants from the surface of the water (e.g., skimmers) and using other measures for preventing the oil from escaping into the open sea. In Balinskyy’s view, even if these measures were implemented, then this was done either too late or ineffectively.

“What started as a war crime by the enemy has, due to the incompetence of officials, transformed into a regional environmental catastrophe,” Balinskyy later wrote in a post on Facebook. He bolsters this argument with a series of radar images taken by the Sentinel-1 satellite, reflecting the gradual deterioration of the situation.

Unfortunately, it is harder to remove vegetable oils from the sea than petroleum products. Liquid vegetable oil is more difficult to collect using oil skimmers, since it is less viscous than mazut and slips through the skimmer. For the same reason, floating booms also work less well with vegetable oils. And dispersant chemicals are not recommended for vegetable oil spills, since many experts believe they can be more harmful to the ecosystem than the oil itself. This means that if a spill is not contained at the very outset, the chances of successfully neutralizing it are limited.

Balinskyy and other activists cite numerous facts that show the authorities’ inability to deal with the consequences of spills. This may indicate that no effective plan for the cleanup of oil spills in the port of Pivdennyi, the Small Adzhalyk Estuary and the Gulf of Odesa was developed in advance, or that it only existed in a formal sense, as a box-ticking exercise.

When the oil reached Odesa, carried along the coastline by the sea current, it was necessary to immediately prevent oil pollution from coastal waters from penetrating into other estuaries where seawater flows, such as the Kuyalnik Estuary, a closed ecosystem where pollution of this kind could have had catastrophic and practically irreversible consequences. So on December 23, 2025, the Kuyalnik National Park sent a letter to the management of Obltransstroi, the operator of the region’s drainage facilities, with a request to immediately cut off seawater from entering the estuary if sunflower oil was found in it. It appears that the estuary’s pollution was averted.

Sea birds in distress

When Odesans saw masses of oil-coated, freezing birds on the beaches on December 24, the question was naturally how to help them. Igor Belyakov, the director of Odesa Zoo, took to social networks and media outlets to call for people to gather up affected birds, place them carefully in boxes and bring them to the zoo. He warned that it would not be possible to warm up and clean the majority of these birds independently at home. For its part, the zoo had already made the necessary preparations and trained volunteers to wash the birds of oil, dry them and feed them during their stay.

Over the next two-three days, concerned citizens brought over 300 birds to the zoo, most of which were highly specialized fish-eating species: great, little and black-necked grebes, which do not tolerate captivity well.

On one hand, these birds have a slightly greater chance of survival than those that became stranded in the mazut slicks in the Kerch Strait a year earlier, since liquid oil is far less toxic, meaning mortality from poisoning will be far lower. But on the other hand, it is more difficult to wash sunflower oil from feathers than petroleum oil, as surface-active agents (shampoos) are less effective with it than with hydrocarbons. Caring for birds that feed only on small fish, which need access to water (ponds, pools, rivers) and are completely unaccustomed to people, is naturally the most challenging part of the task of rehabilitation.

After just three days, the zoo’s staff realized that they would not be able to cope on their own. Giving first aid and partially cleaning the birds was still within their capabilities, but the zoo did not have the capacity to keep and feed the birds for an indeterminate period—it lacked both the space and personnel. Once again, Belyakov turned to the concerned public for help, calling on them to take in rescued and washed birds for further care.

Most of the birds brought to the zoo by citizens for rehabilitation were distributed in large groups between specialists and educational institutions, such as the biology faculty of the I. I. Mechnikov National University, the Agrarian University and the veterinary clinic of Leonid Stoyanov. But there were also volunteers, who took in one or two birds. Belyakov told the media that the zoo is maintaining contact and providing consultations to all those who have accepted birds for care. At present it is unclear how many birds have survived.

“The biggest problem is that apart from the zoo and people with an interest in it, no one is addressing this situation [rescuing the birds],” explained Yana Titarenko, head of Golos Prirody (Voice of Nature), the public organization that supports the zoo, in an interview with Ukrainian Radio on December 27. “There’s been zero response from the Odesa authorities and zero response from the regional authorities. We have two environmental departments—the Odesa City Council and the regional department within the regional council—but they’ve completely ignored this issue, pretending that nothing has happened. So the zoo is now being forced to rescue these birds on its own.”

The situation in Odesa remains critical. The continuing intense Russian bombardment is causing periodic power and heating blackouts in buildings, including those where injured birds are being rehabilitated. At the same time, unprecedented freezing temperatures and snowfall on the coast make wintering extremely difficult for waterfowl, which need open water to survive. In some places this water is still covered with an oily film. Small numbers of volunteers continue in their efforts to save freezing birds, while the zoo’s specialists provide advice on how to support birds that are wintering near water in this harsh winter.

Read more: Safe haven: How Ukraine’s zoos are saving animals in spite of war

On January 27, clumps of vegetable oil and dead birds were found on a bar in the Tuzly Lagoons National Nature Park (Odesa region), 150 kilometers from the site of the spill, during a survey of the site. The same day, local residents discovered large numbers of Black Sea seahorses—a species listed in the Red Book of Ukraine—washed up on the Odesa coast following a storm. “In different sectors I counted up to 35 individuals in one square meter of coastline,” reports Vladyslav Balinskyy, who believes that one of the most likely causes is that some of the oil settled onto the seabed, forming viscous polymer films. The die-off may also be the result of poisoning from industrial waste, a powerful storm or even anomalous cooling. Specialists from the Institute of Marine Biology at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine did not find typical pollutants in water tests. The seahorse is a marker of the general health of the ecosystem, and this event may be evidence of a comprehensive deterioration in the ecological situation in the Gulf of Odesa as the war goes on.

What can be done to reduce the negative impact of spills?

Since the full-scale invasion, the Black Sea has become an arena for environmental disasters and crimes. The consequences of most of them are hard to assess amid ongoing military action.

Read more: Impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov

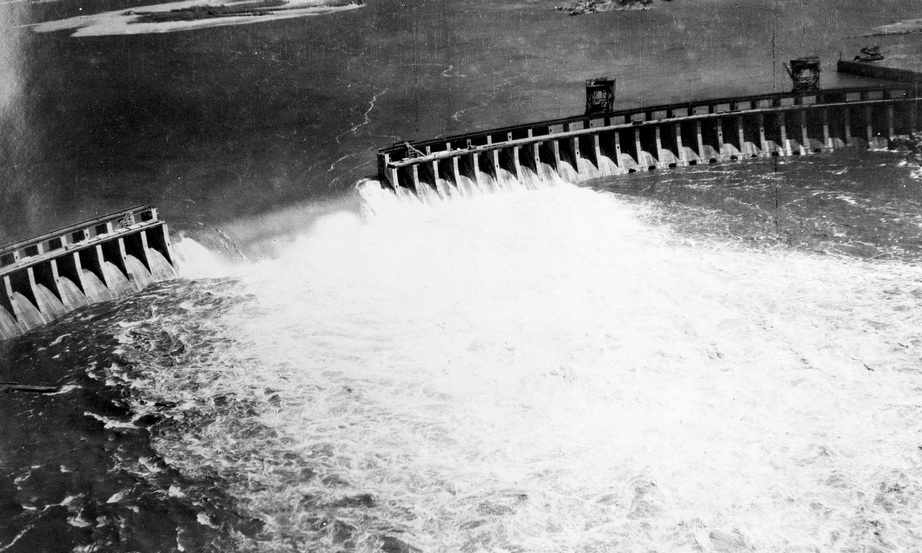

Some impacts are unprecedented and thus virtually impossible to predict. For example, the artificial freshwater flood unleashed by the destruction of the Kakhovka Hydropower Plant covered and clouded many thousands of square kilometers of surface water with sediment. The catastrophic fuel oil spill resulting from the sinking of two tankers in the Kerch Strait was slightly less unexpected, but also unique in its own way.

Read more: How restoration of Ukraine’s ecosystems is being discussed at European conferences

Other impacts, such as the consequences of the explosion of ammunition and the sinking of ships, today look entirely foreseeable. Oil spills from bombed-out terminals have also become almost routine.

These authors believe that oil spills resulting from targeted missile attacks have predictable consequences and therefore require improvements aimed at prevention and an early and comprehensive response system for environmental threats caused by such attacks. The experience we have already accumulated in Ukraine’s southern ports should allow us to draw conclusions as to which engineering control measures will be most effective in preventing oil from entering waterways, and what technical means and trained personnel are needed to ensure the rapid cleanup/localization of a spill in a given waterway if it does happen. These plans should be comprehensive and include targeted measures to protect local natural ecosystems and species.

The response to the 2024 fuel oil spill in the Kerch Strait demonstrated the urgent need for coastal cities to maintain veterinary clinics capable of receiving, cleaning, and caring for large numbers of birds injured by spills for several weeks. The recent experience of Odesa confirms this.

Translator Alastair Gill

Main image source: ukrinform