Translated by Jennifer Castner

The war has exacerbated the food crisis, in part because Ukrainian agricultural products cannot be sold on the world market. UWEC Work Group has been covering how a new round in the food crisis results in destruction of natural ecosystems.

The first agreement that the conflicting parties managed to reach specifically concerns grain transportation from Ukraine to global markets and removing barriers that hinder trade in Russian agricultural products and fertilizers. The grain deal permitting the resumption of commercial grain exports by ships from three Ukrainian ports was widely advertised by the United Nations as a means of preventing starvation in the poorest countries. Just two months after the deal was reached, it has drawn criticism from both sides of the war’s barricades.

“We did everything we could to ensure Ukrainian grain was exported,” said Vladimir Putin, speaking in Vladivostok at the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF). “Almost all the grain exported from Ukraine was sent not to developing nations but to European Union countries.” Putin also claimed that “only two of 87 ships” were loaded through the UN’s World Food Program (WFP) for starving countries and promised to again consider the possibility of throttling grain exports to Europe.

To some observers, such as the editors of the Blue Pass portal, it seems suspect that, at the same time that the Black Sea corridor agreement was confirmed, the UN entered a three-year memorandum of cooperation removing trade barriers for Russian grain and fertilizers, the very country that unleashed the war.

This analysis examines the real and mythical benefits of the first joint mechanism created during the war to solve an international challenge.

Food crisis

In recent years, Ukraine and Russia have accounted for a significant share of global wheat, barley, corn, sunflower seed, and sunflower oil exports.

Figure 1. Top wheat exporters in 2021. Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), May 2022.

Russia is also the most important supplier of fertilizers to international markets. The war has caused a rapid rise in global food and fertilizer prices as exports from Ukraine and Russia were called into question.

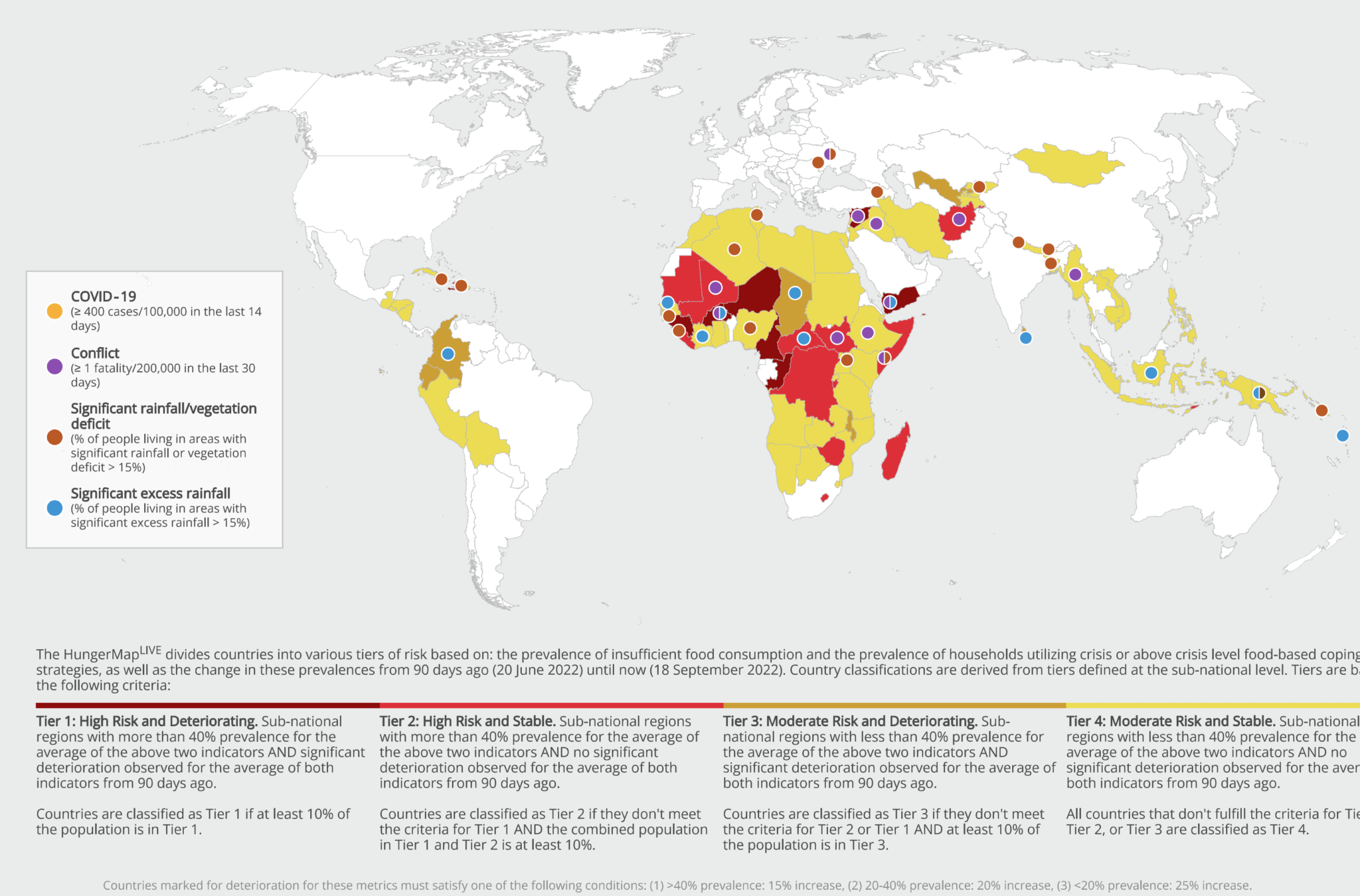

Figure 2. Food security outlook as of 18 September 2022. World Food Program. Legend: high risk and deteriorating – dark brown, high-risk and stable – red, moderate risk and deteriorating – khaki, moderate risk and stable – yellow). Source: WFP Hunger Map.

In August 2022, the UN reported that, “345 million people will be acutely food insecure or at a high risk of food insecurity in 82 countries with a WFP operational presence, implying an increase of 47 million acutely hungry people due to the ripple effects of the war in Ukraine in all its dimensions.” Compared to May 2022, the number of countries at risk for hunger grew from 24 to 28. The main reason for the deteriorating situation is the rise in the cost of basic food products in the poorest countries during the war.

In these conditions, the UN initiated agreements for the return of fertilizers blocked by the war in Ukraine and Russia to world food markets.

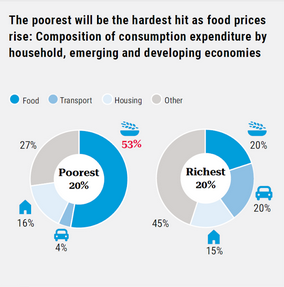

Figure 3. Global price increases for food pose the greatest risk to the poorest segments of the world’s population, which spend half of their income on food. Source: Brief 1. Global impact of war in Ukraine on food, energy and finance systems, UN, 2022.

What is the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI)?

The initiative is a rather pragmatic system of agreements between Ukraine and Russia reached through mediation by the UN and Turkey. It facilitates taking the maritime food commodity exports from three Ukrainian ports in the greater Odesa region from the war’s blockade. Vessel traffic is coordinated by the Joint Coordination Center (JCC) in Istanbul, staffed with representatives from Russia, Ukraine, and Turkey as well as UN staff observers. The initiative clearly defines the order of ships from Odesa to the Bosphorus, guaranteeing their safety and using JCC verification procedures. The Center publishes detailed information about each shipment, ports of destination, shipped products and their volume, inspection dates, etc. The agreement is valid for 120 days and can be extended by agreement of the parties.

Figure 4. Wartime grain exports. Source: Ukraine Ministry of Infrastructure announcement.

According to Ukraine’s Ministry of Infrastructure (published in response to claims made by Vladimir Putin), by 8 September 54 ships had transported one million metric tons of agricultural products to Asia, 32 ships carrying 850,000 tons set out for Europe, and 16 ships sailed with 470,000 tons of cargo to African nations.

Between 3 August and 27 September 2022, the JCC registered 231 passages to different ports of destination. In total, they loaded over five million tons of grain and other plant products.

Outbound voyages

| # | Vessel name | IMO | Departure port | Country | Commodity | Tonnage | Departure | Inspection cleared |

| 1 | RAZONI | 9086526 | Odesa | TBD and Türkiye | Corn | 26,527 | 01-Aug-22 | 03-Aug-22 |

| 2 | NAVI STAR | 9590979 | Odesa | Ireland | Corn | 33,000 | 05-Aug-22 | 06-Aug-22 |

| 3 | ROJEN | 9754927 | Chornomorsk | Italy | Corn | 13,041 | 05-Aug-22 | 07-Aug-22 |

| 4 | POLARNET | 9758961 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Corn | 12,000 | 05-Aug-22 | 07-Aug-22 |

| 5 | GLORY | 9288473 | Chornomorsk | Iran | Corn | 66,084 | 07-Aug-22 | 09-Aug-22 |

| 6 | STAR HELENA | 9361213 | Chornomorsk | China | Sunflower meal | 45,000 | 07-Aug-22 | 09-Aug-22 |

| 7 | RIVA WIND | 9301196 | Odesa | Türkiye | Corn | 44,000 | 07-Aug-22 | 09-Aug-22 |

| 8 | MUSTAFA NECATI | 9736690 | Chornomorsk | Italy | Sunflower oil | 6,000 | 07-Aug-22 | 10-Aug-22 |

| 9 | ARIZONA | 9592733 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Corn | 48,459 | 08-Aug-22 | 10-Aug-22 |

| 10 | SACURA | 9497000 | Yuzhny/Pivdennyi | Italy | Soya beans | 11,000 | 08-Aug-22 | 10-Aug-22 |

| 11 | OCEAN LION | 9296248 | Chornomorsk | Republic of Korea | Corn | 64,720 | 09-Aug-22 | 11-Aug-22 |

| 12 | RAHMI YAGCI | 9550852 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Sunflower meal | 5,300 | 09-Aug-22 | 13-Aug-22 |

| 13 | STAR LAURA | 9328936 | Yuzhny/Pivdennyi | Iran | Corn | 60,150 | 12-Aug-22 | 14-Aug-22 |

| 14 | SORMOVSKIY 121 | 8133578 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Wheat | 3,050 | 12-Aug-22 | 15-Aug-22 |

| 15 | FULMAR S | 9370082 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Corn | 12,000 | 13-Aug-22 | 15-Aug-22 |

| 16 | THOE | 9400588 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Sunflower seed | 2,914 | 13-Aug-22 | 16-Aug-22 |

| 17 | OSPREY S | 9300843 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Corn | 11,500 | 16-Aug-22 | 18-Aug-22 |

| 18 | BONITA | 9231286 | Yuzhny/Pivdennyi | Republic of Korea | Corn | 60,000 | 16-Aug-22 | 18-Aug-22 |

| 19 | RAMUS | 9318400 | Chornomorsk | Türkiye | Wheat | 6,161 | 16-Aug-22 | 19-Aug-22 |

| 20 | BRAVE COMMANDER | 9136931 | Yuzhny/Pivdennyi | Djibouti | Wheat | 23,300 | 16-Aug-22 | 21-Aug-22 |

| 21 | PETREL S | 9363883 | Chornomorsk | The Netherlands | Sunflower meal | 18,500 | 17-Aug-22 | 19-Aug-22 |

| 22 | SARA | 9259020 | Odesa | Türkiye | Corn | 8,000 | 17-Aug-22 | 19-Aug-22 |

Beginning of official registry of ships transporting food products along the Black Sea corridor. Source: https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/vessel-movements

The agreement itself does not regulate vessel destinations in any way, but restores safe shipping corridors and thus ensures free trade.

Nevertheless, these 60,000 tons of grain that so outraged Vladimir Putin – grain that the UN purchased for countries experiencing famine in the first month after the corridor was opened – roughly correspond to last year’s levels. According to monitoring by Informall BG, an Odesa-based consultancy, Ukraine supplied over 500,000 tons of food-grade wheat through its Black Sea ports to markets in Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Yemen, as part of the UN World Food Program (WFP) throughout all of 2021.

On 22 July, the same day as the launch of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, the UN and Russia signed a “Memorandum of Understanding between the Russian Federation and the Secretariat of the United Nations on promoting Russian food products and fertilizers to world markets.” The Memorandum is valid for three years, during which the UN will facilitate Russian agricultural trade, trade that is equally as important as Ukrainian products for providing the world with food.

First “war agreement” and its prospects

Together with “all of progressive humankind,” the UN Secretary General legitimately rejoiced at the signing of these agreements. Aside from their anticipated role in stabilizing the costs of critical food products and reducing the threat of famine, these are the first and only agreements made during a war that involves mutual belligerents and seek to solve problems exacerbated by the war itself. Thanks in part to mediation by the UN and Turkey, the first mechanism for constructive interaction between Russia and Ukraine has been achieved, offering hope that it can become a model for resolving other challenges.

At the same time, the agreement became possible because both parties perceive its significant benefits.

Ukraine receives security guarantees for part of their agricultural infrastructure; income from grain sales will be very useful for a depleted treasury, and storage facilities will be freed up for new crops.

According to US State Department data, Ukraine has exported ten million tons of grain using routes through EU countries during the war. In particular, two-thirds of food exports in August passed through Ukrainian and Romanian ports in the Danube delta. However, only small vessels with displacements of 1,000-5,000 tons can call at Danube ports, cargo that must then be transshipped in the Romanian port of Constanța onto marine bulk carriers.

Navigation along delta channels is difficult, and in spring months, there can be traffic jams of 90 or more ships. More importantly, this complicated route is also much more expensive than the route from Odesa. According to Informall BG and GMK data, the total monthly throughput of the “window to Europe” for the export of agricultural products in April-May was only 1.25-1.5 million tons. At the same time, throughput is four to five million tons at greater Odesa ports. In other words, without these ports, export opportunities are reduced by two-thirds. This is why this treaty is so critically important for Ukraine.

Figure 6. Marine ports in 2021 transshipped 48 million tons of grain and provided over 90% of exports of grain and sunflower oil. Source: GMK, May 2022.

In backing this initiative, Russia is shielding itself from blame for worsening famine, especially in the poorest countries in Africa and the Middle East, where it still has many allies. With the UN’s assistance, Russia is also being given an opportunity to restore Most Favored Nation treatment for the export of its agricultural products and fertilizers, or at the least, a guarantee that the terms of trade will not worsen.

In a recent interview, Sovecon Analytical Center Director Andrei Sizov suggested that because Russia trades grain and fertilizers quite successfully even without such an agreement, it is likely that Turkey, as a broker of the agreement, made some additional private promises to Russia about assistance on the world stage. Otherwise, this deal that gives the enemy an important financial outlet is difficult to explain in the context of a bitter war.In implementing these agreements, the UN sees an opportunity to reduce the threat of famine (mainly through price stabilization) and demonstrate the viability of its mechanisms, the effectiveness of which was greatly undermined by the global geopolitical conflict during this war. The first ship was inspected at the JCC in the Bosphorus just ten days after the agreement was signed, a sort of speed record for initiatives within the slow-moving UN. The UN announced that by 14 September the World Food Program (WF) in Ukraine had already purchased 120,000 tons of wheat as a part of humanitarian aid projects.

Figure 7. Black Sea grain exports. Source: UN Data of the Joint Coordination Center as of 14 September 2022.

Turkey is not embarrassed by the fact that it stands to benefit almost the most of all from these agreements. The war has allowed Turkey to strengthen and develop partnerships with almost all parties to the conflict. In addition, roughly one-quarter of ships offload their cargo in Turkish ports, and Turkish officials are reporting that they are buying Ukrainian grain at a discount.

In this fashion, Turkey has both improved its own food security but will also be able to profit off the resales of grain or grain products in African and Middle Eastern states. Lastly, beginning 7 October, Turkey will quintuple the price for passage through the Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits in accordance with rights granted to it by the Montreux Convention of 1936.

Will the UN come to your aid?

As for the Memorandum between the Russian Federation and the UN, from 22 July to 12 September, no clear statement could be found on either UN information resources or Russian government websites. On 22 July, the day of the signing, Minister Sergei Lavrov explained that, “the document is about eliminating obstacles created by the US and the EU in the financial, insurance, and logistics sectors and achieving specific exemptions for these products from restrictive measures.”

Later, when visiting Egypt, he spoke disparagingly: “The UN Secretary General … volunteers to seek the removal of illegitimate restrictions. Let’s hope he succeeds. Regardless, we understand how to work toward full implementation of contracts between Russia and our Egyptian colleagues.” In other words, no such memorandum is needed to conduct trade with such key food buyers as Egypt.

At a press briefing on 22 July, UN Deputy Spokesman Farhan Haq, said that the UN will work with government and commercial structures to eliminate “overcompliance of the private sector,” but hesitated to answer questions about where and how the UN will apply efforts towards it.

The Russian Foreign Ministry delayed announcing the memorandum until 12 September as partial “covering fire” for Putin’s claims. The announcement streamlined the UN’s role: “The Secretariat will seek to work with competent authorities and the private sector to achieve specific exemptions for food and fertilizers, including raw materials (such as ammonia), produced in Russia,” from the restrictions imposed on Russia. There were no answers to questions of “How? Where? How long?” or how to evaluate results given that none of these goods are subject to sanction in the first place.

Effective implementation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI) is simple to track and measure. Indicators include, for example, export volumes for agricultural products. In the case of the Memorandum, tracking progress is challenging in principle. Its goals will never be fully achieved as long as the war continues. After all, in many respects the nature of “overcompliance” is based precisely on the unwillingness of many private companies and banks to participate in Russia’s trade operations during the war, even for humanitarian purposes blessed by the UN.

What limits Russian food exports?

The war has not presented a radical obstacle to the Russian trade in food and fertilizers. In July 2022 at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, Deputy Prime Minister Victoria Abramchenko announced that food exports had grown by 16% compared to 2021. According to Agroinvestor data, experts projected 5.9 million metric tons of wheat exports from Russia in July-August, a 27% decline over the previous year. In September, exports may increase to 4.1-4.3 million tons, up from 3.65 million tons in August, compared to 4.7 million tons shipped in September 2021.

In the interview mentioned earlier, Sovecon Director Andrey Sizov explains this “shortage” by the fact that high export duties and a strong ruble made Russian grain too expensive and uncompetitive on the market in spring and summer. According to the Russian Ministry of Agriculture’s forecast, the gross grain harvest in 2022 may reach 130 million tons, including 87 million tons of wheat. Official plans for export deliveries in the 2022-23 season are roughly 50 million tons of grain (up to 30 million of which will be repeated in 2022).

Vice-President of the Russian Grain Union Alexander Korbut bluntly told Agroinvestor that the main difficulty in exports for Russian companies was and remains competition with other countries. World Food Organization reports on food systems indicate that Canada, the United States, and Ukraine will have strong grain export surpluses this year, as will Russia. Ukraine alone expects to export 25-40 million tons of grainˀ and will have grain surpluses for export this year, as will Russia. Russian media have repeatedly stated that Ukraine’s role in grain exports is inflated and that Russia will easily replace it on the world market. Nothing personal, just business, in other words.

This assertion prompts worries about prospects for extending the BSGI in November, given that it is less and less relevant for one of its key participants, a fact that participant has already loudly announced through diplomatic and non-diplomatic channels. However, it is possible that the Russian authorities seek assurances for the resumption of large-scale ammonia exports (used in fertilizer production) through ports in Odesa, a possibility UN officials have already publicly discussed.

If the Soviet era Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline was brought back online, it could facilitate exports of over two million tons of ammonia a year, which, according to the UN, will significantly reduce the deficit and reduce the price of fertilizers.

Black Sea Grain Initiative and famine

Is the BSGI that important for limiting the food crisis in countries experiencing famine if only a fraction of the grain goes to UN humanitarian programs?

Turkish President Erdogan immediately reacted to the desire Putin expressed at the World Economic Forum to re-negotiate this issue. He said, “… I will ask Putin to start deliveries through the ‘grain corridor.’ If grain deliveries from Russia also begin, an optimal distribution system will be created … including for the poorest countries in Africa.” Apparently, he meant that in order for commercial ships to reach Africa, someone must send them there at their own expense, i.e., Russia itself.

As a rule, in order for grain to reach areas where hunger is an issue, some rich sponsor must pay for it. In recent weeks, the United States and Sweden have allocated new funding for the purchase of Ukrainian grain for UN programs. On September 19, the Ukrainian government itself allocated 420 million hryvnias for the purchase of 50,000 tons of grain intended for humanitarian aid in regions facing famine in Ethiopia and Somalia. In total, Ukraine’s Ministry of Infrastructure data show that 280,000 tons of grain will be exported in the near future in support of the UN World Food Program.

Russia’s role in this UN program is not obvious. At a US State Department briefing on the fate of the initiative, the official in charge of sanctions cited the example of a recent WFP grain procurement tender. Russia was allegedly invited to bid, submitted an offer, but did not qualify for the final, having named an exorbitant price. According to the official, Russia has large financial reserves, meaning it could afford to offer discounts for humanitarian purchases and participate in exports for the needs of the hungry.

Even if Russia does not join these humanitarian actions, the initiative will still have a significant effect on countries facing the threat of famine.

The BSGI’s most important role is in stabilizing food markets and lowering the cost of basic agricultural products around the world. According to UN officials, the start of exports along the corridor has already resulted in a significant decline in international prices, although this has not yet led to a decrease in consumer prices for the poorest countries. If the Initiative is not extended, it will signal a return to chaos and may cause prices to rise and markets to destabilize. But large food exporters will earn even more.

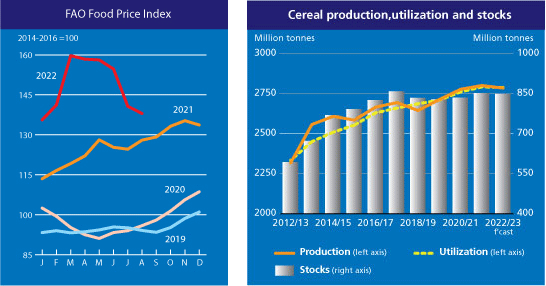

Figure 8. Price index showing significant decline, August 2022. Source: World Food Organization.

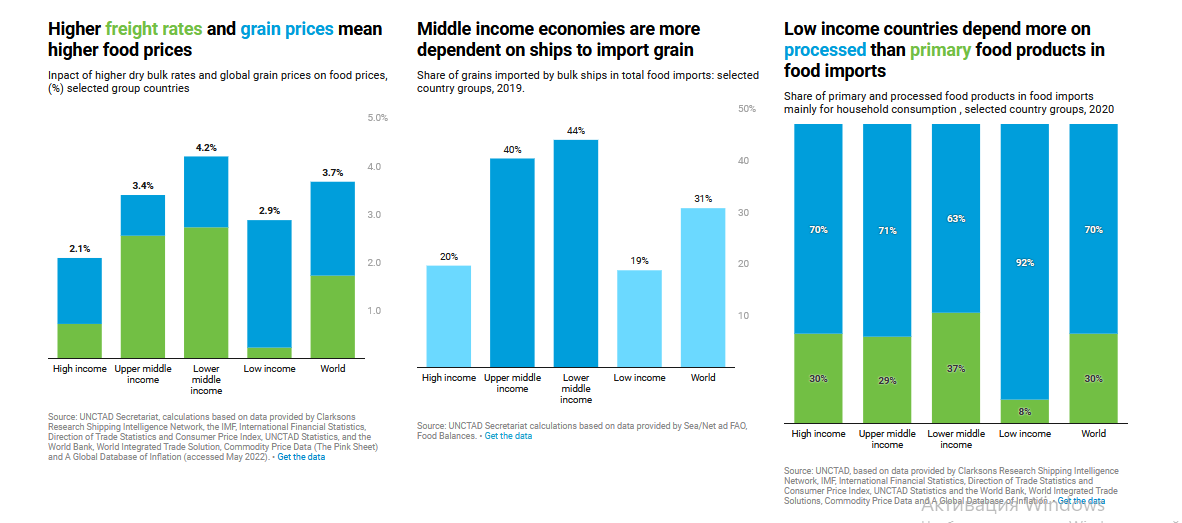

Figure 9. Maritime transport and food needs for countries with varying income. Source: UNCTAD.

The United Nations Conference of Trade and Development (UNCTAD) developed illustrative charts on the impact of food and shipping prices on countries over a range of incomes, showing that low-income countries are the least dependent on maritime grain transport and most dependent on food prices, largely because they buy pre-processed grain.

All this supports the UN Secretary General’s thesis that the Black Sea Grain Initiative is of paramount importance specifically as one measure for reducing world food prices, and that this is its charitable role for the poorest countries.

Will the initiative be good for the environment?

There is one greater threat that could potentially be reduced as a consequence of renewed grain exports from Ukraine. The threat in question is negative environmental impacts.

As UWEC has reported previously, the war-time food crisis has already become a pretext for new exploitation of natural areas with high conservation value in many countries. In June, UWEC discussed trends in Ukraine, Russia, Europe, and even Brazil, where President Jair Bolsonaro combined the looming threat of fertilizer shortages with potential disruptions of Russian and Belarusian exports as an excuse to advance a bill aimed at allowing the extraction of mineral resources and fossil fuels on Indigenous tribal lands in the Amazon. Fortunately, in April and May, Brazilian companies successfully purchased enough fertilizer from Russia, and the law was again shelved after a major protest.

Unblocking maritime trade of agricultural products reduces the incentives that food-buying countries have for developing natural areas and increasing the supply of food on the world market at more affordable prices. On the other hand, the same initiative could potentially increase incentives for plowing new farmland and other environmentally destructive actions in Ukraine and Russia. This means that protective measures must be taken now to prevent this from happening.

A chance to save the deltaThe war-time blockade of the Black Sea’s main ports prompted attempts to partially compensate for that lack of port facilities by moving traffic to the Danube delta. Enacted on 12 May 2022, a law “On amendments to some Ukrainian laws regarding regulatory aspects of land relations under martial law” legalized the use of lands within protected areas for the construction of sea ports and commercial agricultural production.

One could hope that this is not connected to the Danube delta, a biosphere reserve operating under the UNESCO “Man and the Biosphere” program, but a change was recently made to transitional provisions of Ukraine’s Land Code. The amendment stated that during martial law the transfer of land plots to state or communal property for rent is permitted for “… the placement of river ports (terminals) on the Danube River….” In other words, the ban on the construction of ports in a protected river delta has been lifted.The creation of ports and the development of shipping were, historically, the most important contributors to the destruction of Danube ecosystems. In particular, two of its channels that pass entirely through the territory of Romania have already been artificially straightened in many places, losing their natural ecosystem functions as a result. The channel that runs along the border with Ukraine has kept its natural shape. Recent legislative amendments and announcements by the Ukrainian Sea Ports Authority (USPA) about the creation of a deep-water channel leave no doubt that the protected delta is once again in danger.

Figure 10. Presumed route of a deep water shipping channel in the Danube delta. Its operation became possible following the evacuation of Russian troops from Snake Island, a convenient location for effectively blocking navigation in the northeastern Black Sea. Source: Liga Net

Given the high costs and logistical inconvenience of transporting and transshipping goods in the Danube delta, there is hope that sustainable restoration of a safe transport corridor from Odesa to the Bosphorus can cross costly construction of new ports and dredging the Danube delta channel in Ukrainian territory off the agenda. Beyond that, the legality of that type of construction in the middle of a biosphere reserve is highly questionable.

Food for the future

The Black Sea Grain Initiative is certainly important for stabilizing the global food crisis. It is effective and even gathering speed. The memorandum between the UN and Russia also plays a stabilizing role in food commodity markets, although more as insurance against the potential for escalating sanctions, a means of excising food and fertilizer from future sanctions packets. At the moment, Russia is coping with trade challenges for food and fertilizers even without the UN’s help. The future of the BSGI is unclear. Russia’s leadership is clearly attempting to use agreements to weaken the sanctions regime as a whole and may be willing to sacrifice the BSGI in that struggle.

The food crisis has negative environmental consequences, particularly where wilderness areas face new development. Easing the crisis by expanding trade in grains and fertilizers can reduce environmental pressure in importing countries, but may increase that pressure in exporting countries. In Ukraine, in the short term, the BSGI may aid in avoiding the construction of new ports and canals and thereby preserve the Danube Biosphere Reserve. UWEC Work Group will revisit this pressing situation in the near future.

Main image credit: epravda.com.ua

Comment on “First wartime agreement in jeopardy?”