by Viktoria Hubareva using UWEC Work Group research materials

Translated by Alastair Gill and Jennifer Castner

The Kakhovka hydropower station was built in Ukraine from 1952-56. Its reservoir was the largest of the six reservoirs in the Dnipro cascade, covering an area of 2,155 square kilometers – almost a third of the area covered by all six reservoirs and around 40% of the total volume of all Ukraine’s reservoirs. The gigantic facility had several functions: the production of electricity, increasing the depth of the shipping channel in the Dnipro along the Kakhovka-Zaporizhzhia section, supplying water to cities and villages, and irrigating crops.

On 6 June 2023 Russian troops blew up the dam and the hydroelectric infrastructure, destroying it, and the accumulated water in the reservoir was released.

Arguments in the media for the restoration of the Kakhovka Dam show that supporters of restoration – primarily state bodies and the state-run hydropower enterprise Ukrhydrenergo – intend to try and preserve the agricultural system. That is, they are seeking to restore the reservoir and dam to its previous Soviet scale.

Rebuilding the hydroelectric station means restoring infrastructure that is wasteful by modern standards. Yet it appears that the decision to rebuild the Kakhovka Dam has already been made – far too hastily..

Climate change and the inefficient use of power

Three large canals for water supply and irrigation flow out of the Kakhovka reservoir: the Dnipro-Kryvyi Rih Canal, the North Crimean Canal and the Kakhovka Canal. Most of the land that was irrigated in the past now lies in occupied territory. Only the smallest of the three canals remains undamaged and within Ukrainian-controlled territory: the Dnipro-Kryviy Rih Canal.

Before the beginning of the full-scale war, these canals diverted more than half of the Dnipro’s water (roughly 940 of 1670 cubic meters) and irrigated 5,800 sq km of farmland. In turn, the pumps used 20% of all power generated by the Kakhovka station, and in the hottest and driest season they required the hydroelectric plant to function at full capacity. Essentially, the station worked to maintain the irrigation system.

At the same time, water use efficiency was low in nearby agricultural areas, a situation which was only worsening as global climate change accelerated. The Kakhovka Dam is located at the heart of Ukraine’s steppe zone, a highly arid territory where the large proportion of plowed land has sparked rapid desertification processes.

In 2013 the North Crimea Canal lost 45% of its water as a result of evaporation and filtration. The latter is a result of water simply dispersing into the soil through the canal bed, built without proper waterproofing in the Soviet period. Furthermore, the fields were irrigated using rainwater capture installations, which led to large losses due to evaporation.

Prior to the destruction of the dam, 1.8 cubic kilometers of water evaporated from the surface of Kakhovka reservoir every year. Given global warming and climate change, this figure can only be expected to grow over time. Ultimately, following the past approach will lead to increased water deficits and reduced discharge in the Dnipro, Bug, and Ingul rivers, as well as to increased salinity, both in the soil and in the Dnipro-Bug estuary. After all, the more water evaporates, the more minerals will be left in the reservoir.

The economic system created around the Kakhovka reservoir largely reflected the technological level of the USSR in the mid-20th century. That is, it was developed before significant climate change and the resulting challenges to environmental standards.

Water can be saved by switching to drip irrigation technology

The service life of a hydropower complex is approximately 100 years. So if the hydropower plant and irrigation systems are restored, Ukraine will lock itself into an outdated mode of energy economy and water use until the late 21st century, thereby depriving itself of an opportunity for progress.

Resurrecting a water-hungry agricultural system hardly aligns with the principles and goals of sustainable development, and a decision to restore the reservoir will leave Ukraine on an old path for another century, at a time when most of the world is already going in a new direction.

In addition, we should not forget that the region’s soils, irrigated for many decades with water from the Kakhovka reservoir, are highly affected by anthropogenic salinization. The region’s steppe rivers (with their high mineral content), which feed indirectly into the Kakhovka reservoir, contributed significantly to accelerating soil salinization, as well as mineralization as a result of pollution from industrial cities. In Soviet times, no real effort was made to offset these processes – and as a result, the entire area that was formerly irrigated with water from Kakhovka reservoir is rapidly becoming unsuitable for cultivation. Any discussion of resuming irrigation must also examine this issue.

Traditional agricultural systems or a fresh approach?

There has been almost no agribusiness for two years now in the temporarily occupied territories formerly irrigated by the Kakhovka reservoir or on the frontline. Most of the tenant farmers have left these areas and irrigation equipment has been either destroyed or stolen. Restoring agriculture in the region will require almost the same investment as establishing it from scratch, not to mention the costs of demining and executing soil safety assessments in the wake of military action. It makes more sense to create a new management system with greater potential.

Options worthy of consideration include changing the composition of the crops grown, introducing drip irrigation technologies, and increasing the share of pasture livestock farming.

In Ukraine, these practices are rather poorly developed, and the country has focused on growing grain crops and exporting products at low prices to countries using Ukrainian grain to successfully develop their dairy and meat sectors. As a result, the cost of livestock production is increasing globally. By using water more efficiently and expanding domestic meat and dairy farming and reorienting it toward pasture grazing, Ukraine may be able to make its rural economy more sustainable.

No longer submerged, the land formerly covered by the Kakhovka reservoir can now be used for grazing. This is exactly what it was used for in the past, when the area was predominantly occupied by pastures and open woodland. Drought years aside, this floodplain region will always have high soil moisture and offer favorable conditions for the natural vegetation typical of grassland areas.

Agroholdings vs. rural communities

During the war, small family farms have turned out to be more stable and adaptable than agribusinesses, and they also play a more important role in supporting local communities.

The role and flexibility of rural communities and small-scale farming during war offers an important avenue for addressing environmental issues. However, the Ukrainian government remains inclined to rely on agricultural holdings as an element of post-war reconstruction, especially on liberated territory. European Union policy, particularly the European Green Deal, will also favor small agricultural enterprises as more environmentally friendly and adaptive.

For this reason, local rural communities on the shores of the former Kakhovka “sea” need to be provided with maximum support now. This could include the opportunity to use areas of the exposed bed for sustainable types of agriculture – haymaking, for example. At the same time, local residents should be allowed to use parts of the reservoir bed (as long as no construction or plowing is involved), but should avoid developing areas important for the restoration of biodiversity and ecosystem services. The best solution may be a transition to labor-intensive types of management, which create a higher added value per unit area than the practices previously in use around the Kakhovka reservoir.

A recently registered government draft bill that proposes a 15-year moratorium on any agricultural use for the former reservoir contradicts the sustainable development needs of rural communities along the lower Dnipro.

To build or not to rebuild: Soviet-era dam or watershed ecosystem restoration?

Soon after the Russians destroyed the Kakhovka Dam, the Ukrainian government approved a resolution on rebuilding the huge infrastructure facility. The main customer will be the state-owned enterprise Ukrhydroenergo.

The company wants to build a new hydroelectric power plant with an output of 550-600 megawatts – a significant increase on the maximum 335 megawatts produced by the destroyed Kakhovka HPP. Yet this will produce little increase in electricity generation – no more than 5%. There is not enough water in the Dnipro for more. Ukrhydroenergo wants the new hydroelectric station to function at maximum output, which means the water level in the lower pool (downstream of the dam) will fluctuate several times a day, with waves of floodwater reaching the Black Sea. This is unacceptable due to the great vulnerability of the lower Dnipro floodplain, especially considering its environmental status. Over 100,000 hectares of European Emerald Network protected areas lie downstream of the Kakhovka Dam, as well as the floodplains of the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve and two national parks. Constant fluctuations in water levels are therefore unacceptable, since they are incompatible with the natural dynamics of these natural areas.

However, filling the Kakhovka reservoir will be possible only after the shores have been cleared and the Dnipro bed trawled to remove land mines. Otherwise, abandoned mines will float into water intakes and damage them. The dense forest that is already growing on the exposed bed of the reservoir will need to be clear cut, which will also be possible only after demining is complete.

One option for replacing the total average annual production of 1.4 billion kW/h of electricity generated by the Kakhovska HPP (or the 550-600 MW capacity plant planned to replace it) is to build solar power plants with a total capacity of 1,200 megawatts, for which an area of 2000-2500 hectares (just 1% of the Kakhovka reservoir) is sufficient.

Rebuilding the Kakhovka Dam is not only a technical issue, but also an environmental one

As studies in 2023 showed, almost immediately after the reservoir was drained, the natural floodplain forest that was characteristic of this area before the HPP’s construction began to grow back. Within just six months, young trees had begun to spring up on a large area of the reservoir bed.

Restoring degraded natural ecosystems forms the basis of sustainable development in EU countries and one of the key objectives of the European “Green Deal”. In recent years, European states have increasingly taken forward-looking decisions aimed at mitigating global climate change and guaranteeing a secure future for the entire continent. Back in May 2020, the European Commission presented perhaps the most ambitious environmental document in European history, the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 – Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. The return of natural vegetation on the site of the Kakhovka Reservoir will make it possible to restore up to 1,800 square kilometers of natural ecosystems (of which at least 1,000 sq km will be climate-resilient forests) and make about 250 km of the Dnipro free-flowing, the largest environmental project of all time. Restoring such a vast ecosystem would be a decisive Ukrainian contribution to the European Union’s proposals to revive ecosystems by restoring the natural flow of 25,000 km of rivers by 2030.

If, however, the Kakhovka reservoir restoration project goes ahead, it will be necessary to destroy all of these 1,800 square kilometers of natural ecosystems that have already begun to form. And most of these ecosystems will be forests, the destruction of which is completely anathema to the principles of sustainable development and directly contradicts Ukraine’s goals to increase forest cover.

There is, however, an alternative – making a bold transition to new renewable energy, energy which will be effective in the face of climate change and the increased water shortages that are bound to accompany it.

Solar arrays and gas digesters instead of hydropower

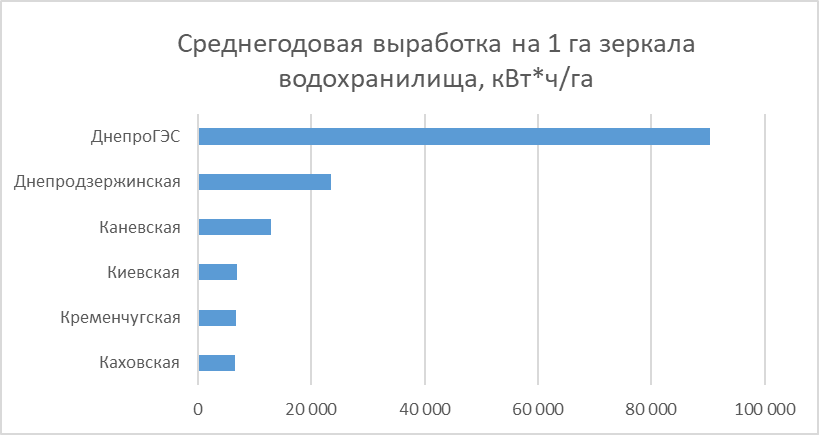

On average, the Kakhovka hydropower plant’s annual output totaled 1.42 billion kilowatt-hours. Just 20-25 sq km of solar panels are required to generate the equivalent amount of electricity. The surface area of Kakhovka reservoir is a hundred times larger yet – 2,155 sq km. In other words, solar energy requires one-tenth the amount of land required by the Kakhovka HPP.

The Kakhovka HPP requires more electricity in summer months to pump water for irrigation and to power tourism and air conditioners. Moreover, these demands consume many times more electricity than that which is needed for lighting.

Most productive in southern Ukraine, solar power is well-positioned to replace Kakhovka’s lost generation output. There are a number of reasons for this.

Even with increased power, an updated Kakhovka HPP will not be able to operate in an environmentally safe way at peak demand.

As described above, operating a hydropower plant at peak demand will inflict tremendous environmental damage on the region downstream of Kakhovka. HPPs operating along the Dnipro River channel are the best choice for operation at peak demand, but definitely not the proposed new prototype HPP at Kakhovka.

With its decentralized nature, solar energy is inherently more stable in wartime conditions and ongoing shelling and can be developed even now.

When it comes to shunting production capacity, developing gas digester capacity is also useful, given that electricity from biogas provides maneuverable generation in windless weather. Increasing the share of livestock farming and feeding a mixture of plant and animal residues into biogas digesters dramatically increases biogas yield (a synergy between livestock farming and energy production).

Modern energy storage technologies can also be put to work, including electrochemical batteries that balance electricity supply without creating hydropower capacity.

How to handle logistics?

One argument used by the proposed Kahkhovka HPP-2’s supporters is transportation infrastructure. The Kakhovka reservoir served as a transport artery for shipping and road infrastructure was needed along the former reservoir’s shores. There are also counterarguments to these claims as well.

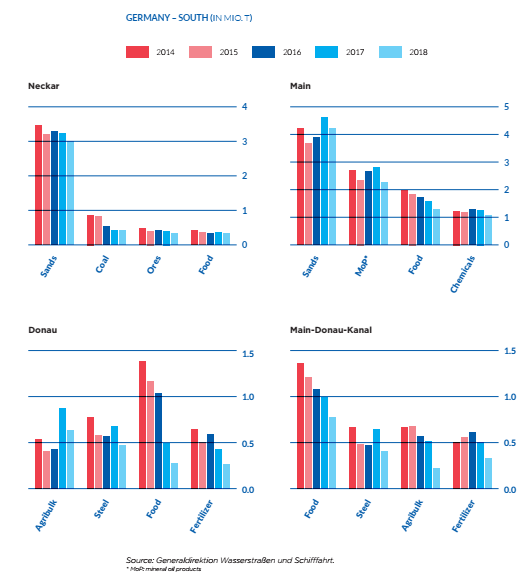

The share of river navigation in transportation is steadily decreasing. In the late 1980s in the USSR, 90 million metric tons of cargo were transported each year on the Dnipro River. By 2013 that number had fallen to 10 million tons of cargo, in 2020 – 6.1 million tons, in 2021 – 8.25 million tons. Climate change-related decreases in the Dnipro’s discharge will further limit the role of river shipping. This dynamic is not only relevant for Ukraine, but also for European rivers.

The river vessels used on the Dnipro are small in size, with an average displacement of less than 1,000 tons. Locks at Dnipro dams are small, 17 m wide, and do not permit passage for large ships. By weight, the main cargo is grain headed for export on sea vessels. Unregulated parts of the Dnipro River have depths sufficient for the passage of these small vessels.

In areas where the river is too shallow, the navigation channel can periodically be dredged, a much cheaper and less environmentally destructive approach than restoring the dam reservoir. Such actions are already carried out annually in the navigation channel of reservoirs.

But in order to restore navigation in the Dnipro’s lower reaches, a new river fleet must first be developed. The existing fleet has been almost entirely destroyed by the war. In all likelihood, the new fleet would largely be composed of small, unpiloted ships.

When it comes to land-based vehicle transportation, bridges can be rebuilt and ferry crossings restored across the Dnipro. If reconstruction of the dam is abandoned, a bridge could be erected connecting Nikopol and Enerhodar in addition to Antonovsky Bridge in Kherson and the bridge over the former dam in Novaya Kakhovka. Such a new bridge would improve connectivity between the river’s left and right banks at Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, further contributing to the region’s economic development.

Time factor

At present, the Dnipro’s left bank – the location of the former Kakhovka reservoir – is occupied by Russian forces. The frontline follows the river, and the lands around it (both on the reservoir’s former banks and the newly exposed bottom) are heavily mined. As a result, rebuilding the HPP is not possible, nor is any other work on the territory of the former reservoir.

The destroyed dam’s foundation must be studied in order to estimate the costs of any reconstruction. This is also not possible until Russian troops vacate the area. No one can say how long the war will continue or how long Kherson’s left bank will remain occupied.

Efforts are already underway to adapt water supply to new conditions on the river’s right bank, occupied by Ukrainian troops. Water supply through the Dnipro-Kryvyi Rih Canal resumed in 2023, and work on the construction of a new water main is nearing completion. This construction should fully meet the water needs of Kryvyi Rih and smaller right-bank cities, which depended on Kakhovka reservoir for water supply.

A contemporary project to restore the region’s economy (without a hydroelectric power station) can be implemented in two stages. The first stage – creating a modern infrastructure network and modern agriculture on the northwestern right bank of the Dnipro – can be started as early as in 2024.

An energy and agricultural project on the Dnipro’s eastern left bank and a transportation infrastructure initiative to establish roads, bridges, and ferries as well as navigation of the Dnipro River from Zaporizhzhia to the river’s mouth can occur after the territory is liberated from Russian occupation and de-mined. Experience gained in implementing similar work on the river’s right bank can be put to work on the left.

It seems understandably much simpler and faster to estimate the cost of rebuilding the hydroelectric power plant and economic system that existed pre-war than understanding the cost of modernization. Government agencies and large semi-governmental enterprises are also often more interested in maintaining the status quo than making changes. As a result, efforts to lobby a morally and technologically outdated plan should not be underestimated.

Lastly, it is in Europe’s interests to gain Ukraine as a strong, modern, post-war state with a modernized economy. It is only such a Ukraine that can clearly demonstrate the collapse of Putin’s expansionist project.

Main image source: Wikimedia

Comment on “Rebuilding the Kakhovka Dam is a mistake, but what should be done instead?”