Eugene Simonov

At the end of August, the fate of Kakhovka Reservoir was the subject of detailed consideration at two major international conferences that took place in Stockholm (Sweden) and Tartu (Estonia). Prior to that, although the fact of the dam’s destruction had, of course, long aroused international interest and sympathy, there had been no detailed discussion of what to do next and what kind of support Ukraine needs in Europe. Such a discussion with European partners is extremely important, given that restoration of the Lower Dnipro region will take place in the context of European integration and with the assistance of European institutions.

World Water Week

On 25 August, during World Water Week in Stockholm, experts discussed the issue during an event called “Destroyed Kakhovka Dam in Ukraine – Current and Future Challenges” on 25 August, organized by the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and the Swedish University of Agricultural Research. The discussion was moderated by Brian Kuns, a Swedish scientist with experience in agricultural and environmental research in southeastern Ukraine. The diversity of presenters at this event was a pleasant surprise.

In a pre-recorded video, the chair of the High-Level Commission on the Environmental Consequences of the War in Ukraine Margot Wallström emphasized to participants that despite the horrors of the war and its severe economic consequences for Ukrainians, future quality of life depends on the extent to which restoration solutions are environmentally friendly and cutting edge for Ukraine. It is impossible to simply restore what was in the past; support is needed to build a better future for Ukraine and this is in fact the Commission’s task.

In this sense, the Kakhovka Reservoir is the most well-known example. All restoration options must be considered and publicly discussed, a process that is explicitly laid out in the “Green Deal for Ukraine” – a set of the Commission’s primary recommendations.

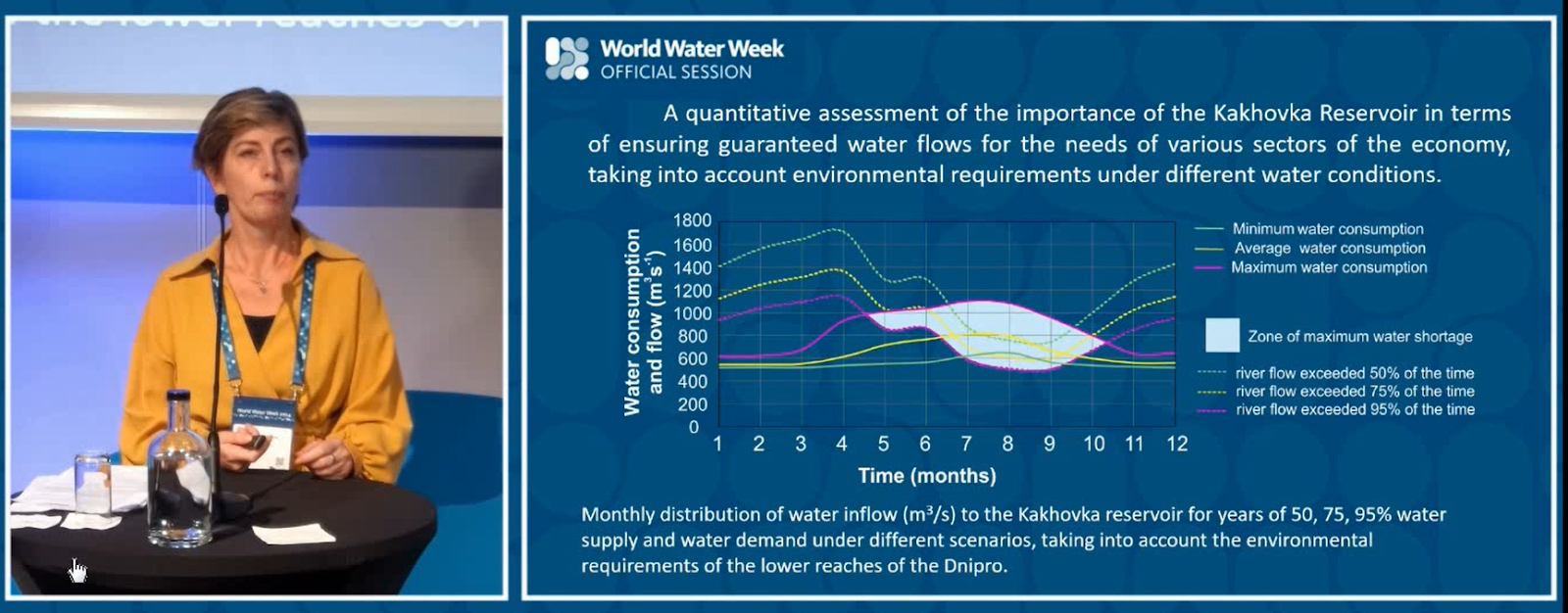

A perfect example for Wallström’s thesis is the expediency of restoring the past. Ukrhydroenergo representative Oksana Hulyaeva spoke about the importance of the Kakhovka hydropower plant (HPP) for the Soviet Union and Ukraine. The plant primarily regulated water supply to municipalities, fed an irrigation system, and supported the ecological state of ecosystems downstream.

The presentation showed that the reservoir supplied up to four km3 of water per year to population and industry, and up to an additional six km3 of water per year for agriculture.

Half of the water destined for agriculture was lost en route to consumers, and another two km3 of water evaporated from the reservoir’s surface annually.

In addition, operation of the Kakhovka and Dnipro HPPs, as well as the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power and Thermal Power plants – Ukraine’s largest power plants – depended on the reservoir. The Kakhovka hydroelectric complex met 40% of the nation’s freshwater needs.

Listening to the report, one could only be amazed at the vulnerability of the centralized system, the critical needs of which were met by a single giant hydroelectric complex.

According to Hulyaeva, if it is assumed that Ukraine’s future economy will remain water-intensive and fixated on a single source without restoring the reservoir, then the entire output of the Dnipro River would be diverted in July and August in low-water years. Accordingly, the main role of a restored Kakhovka reservoir would be environmental, redistributing water to support the needs of unique ecosystems along the Lower Dnipro and the delta estuary, in other words to meet the environmental flow demands (defined as no less than 500 m3/second). Reading the report between the lines then, it could be understood that Ukrhydroenergo calculated environmental flow standards within the framework of HPP operations, an example of the company’s high environmental awareness.

Ecology Department Chair at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Viktor Karamushka, who grew up on the banks of the Kakhovka Reservoir, devoted his presentation to the terrible immediate consequences of the sabotage of the Kakhovka HPP. He listed the human casualties, ecosystem and industrial losses, area of agricultural land deprived of irrigation water, etc. Nevertheless, when asked if the dam should be restored, he answered that it depended on the needs of residents and economic activity taking place there post-war, and that a decision now would be premature.

Watch the webinar recording: “Environmental consequences of the destruction of Kakhovka HPP’s dam”

Marine biologist Halyna Minicheva (Director of the Institute of Marine Biology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine) emphasized in her talk that despite the enormous stressors, the marine ecosystem quickly coped with the short-term environmental consequences of the emptying of Kakhovka Reservoir. Nevertheless, the long-term consequences of the large volume of organic waste that settled on the bottom of the Black Sea after the flood can be seen in the excessive spread of alien, invasive marine organisms and that that may have a long-term negative effect on the marine ecosystem. When asked about the desirability of restoring the dam, Minicheva answered that this is a difficult question, but continued by noting that the reservoir was an important barrier to the removal of pollutants into the sea, and therefore its restoration could reduce the level of pollution.

Forest on the reservoir bed: log or protect?

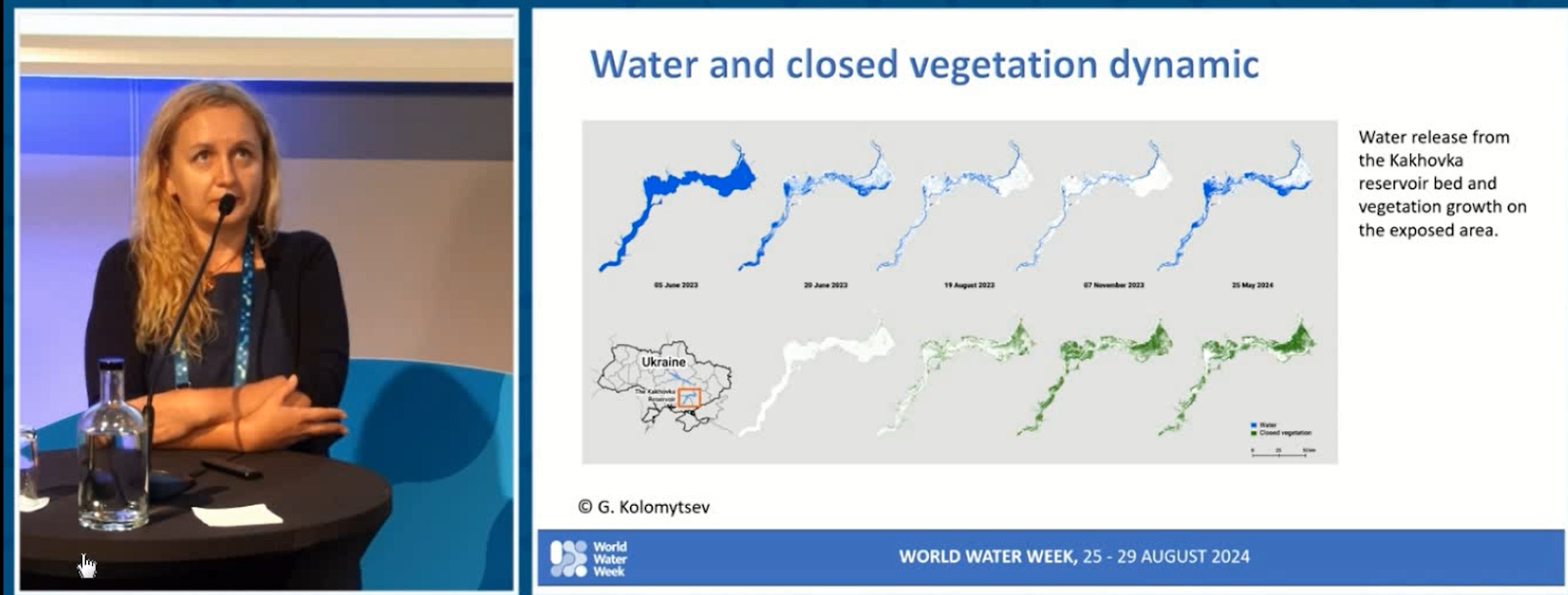

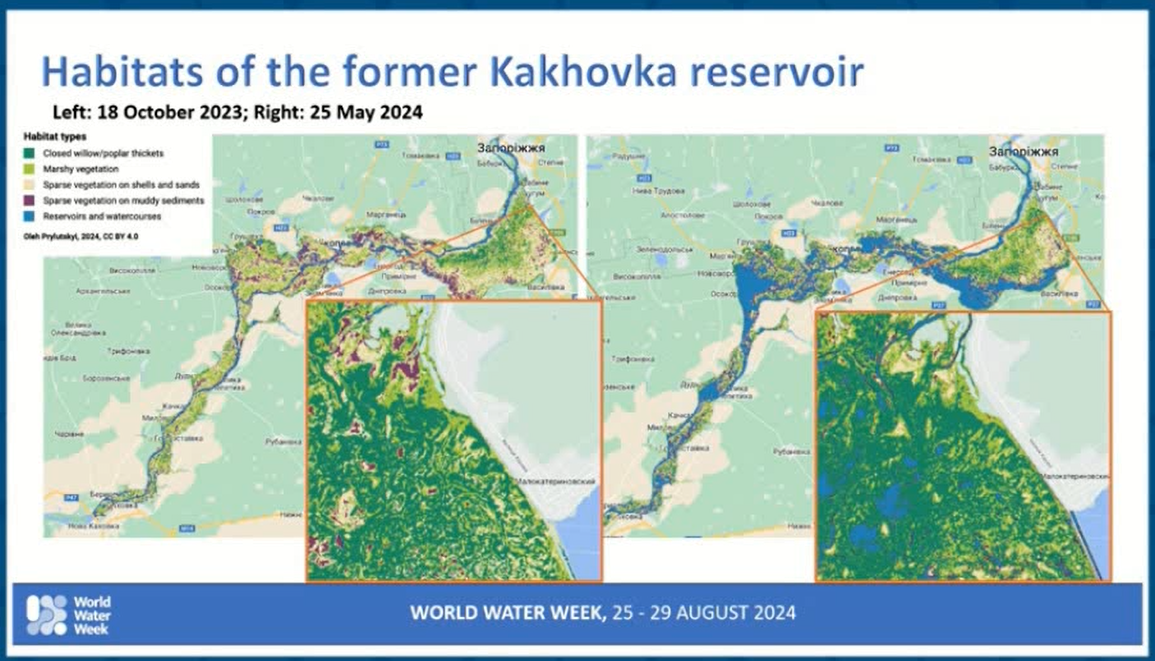

The last to join the debate was geobotanist Anna Kuzemko, who represented Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group (UPG) and the Institute of Botany of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. She spoke about monitoring the restoration of ecosystems on the former reservoir’s bed, work which is being carried out along the front line by scientific and community organizations.

Plant communities on the reservoir’s bed began to recover rapidly just a few weeks after the dam was destroyed. Water conditions in 2024 favored the restoration of floodplain ecosystems, and new willow forests have already reached three to four meters in height, a rapid growth rate of over one centimeter per day. Anna Kuzemko suggested that prior to advocating for the reservoir’s restoration, the cost and value of the services provided by these newly formed ecosystems must be calculated along with any damages resulting from their loss in the event of repeated filling of the reservoir.

An interesting plenary discussion followed the presentations and offered additional information:

– Although the Ukrainian government spoke hastily in favor of restoring the Kakhovka HPP, no justification for this can be provided until the war is over. Millions of people who previously depended on the reservoir have left the vicinity. Whether they will return after the war is unknown, as are the questions of whether destroyed industrial enterprises will resume operations or how quickly agricultural lands will be cleared of mines.

– It is clear that when it comes to power generation, the most urgent task is to restore the Dnipro HPP’s maneuvering capacity, but that is possible without the need to reestablish the underlying reservoir.

– It is important that the question of whether or not to restore the dam has already become a subject of constructive discussion between opponents. High-quality and detailed information is needed in order to evaluate options for future decisions, and that sort of data is difficult to collect during a war. The most critical aspect of the discussion is meaningful comparison of different types of water use in the region. At present, water is delivered to villages in tanks; water pipelines from other sources are extended to cities, and many sites have begun to use groundwater, but this is not always cost-effective. Urgent measures taken today are not necessarily sustainable water supply mechanisms for the future;

– If future farming methods remain rooted in the past, there won’t be enough water in any case. It is very likely that different types of agriculture will develop in southern Ukraine. In particular, Viktor Karamushka recalled that prior to commissioning the hydropower plant, livestock farming was much more developed in the region. Livestock agriculture can be expected to experience a renaissance in the future.

– When asked how the international community could help, Halyna Minicheva suggested collaboration to conduct a basin-wide strategic environmental assessment. Anna Kuzemko endorsed scientific cooperation, but said that today support for the Ukrainian Armed Forces is first and foremost, in order for it to liberate the country’s lands from invaders.

Conference on ecosystem restoration

On the following day, the 14th conference of the European Society for Ecosystem Restoration – SERE-2024 – got underway in the Estonian city of Tartu. This was the first specialized conference to occur after the European Union’s Nature Restoration Law (NRL) came into force on 18 August. As a result, the conference was dedicated to professional discussions on how to jointly support the law’s implementation at all stages, from planning to assessing the effectiveness of restoring ecosystems.

Policy officer at the European Commission’s Directorate-General for the Environment and Nature Restoration Law Florian Clayes explained the schedule and process for implementing the law’s requirements in EU countries. National ecosystem restoration plans must be drawn up by August 2026 for review and subsequent approval by EU bodies in 2027.

The law sets rather ambitious targets for the restoration of 30% of key habitats by 2030, 60% by 2040, and 90% by 2050. That noted, the target for restoring river ecosystems to the state of “free-flowing rivers” by 2030 remains the same as that adopted five years ago: 25,000 km.

At first glance, that target seems less ambitious than the 30-60-90% targets for other ecosystems. Rivers are, however, the most difficult to restore, since water is the most sought-after resource and rivers have many conflicting users. Criteria are currently being developed and tested to assess whether a particular restoration project for a particular section of a river achieves the goals of restoring free-flowing rivers as set out in the law. It would be interesting to conduct such a test for the Lower Dnipro.

In the context of future decisions related to farmland in southern Ukraine, presentations discussing the effectiveness of subsidies for environmentally friendly agriculture were extremely interesting. The European Union pays a lot of money to farmers whose productive agricultural lands maintain high species diversity or preserve specific rare species of plants and animals. At the same time, “all-seeing” drones – junior peaceful siblings of those flying machines that haunt the aggressor on Ukrainian fields today – are being used successfully to monitor plant species diversity. It is quite possible that the EU’s subsidization system will render less intensive dryland (without irrigation) farming and forage cultivation more profitable types of agriculture in Ukrainian steppes than restoration of irrigation systems.

Sessions in conference halls alternated with excursions and training sessions in field conditions. In total, participants chose from a selection of 30+ field trips over the course of the conference.

On the very first day, an excursion dedicated to river restoration showed participants several already demolished dams, as well as the largest dam in Estonia – Linnamae on the Jagala River – a site where hydroelectric generators with a total capacity of just 1.5 MW are installed. The dam is a historical monument, built at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1941, retreating Russian troops blew it up, similar to the recent history of Kakhovka Hydropower Plant. During the years of Soviet occupation the Linnamae stood, full of holes, but in the first years of independence, some enthusiasts found the means to restore it (apparently, as a symbol of the nation’s revival).

Subsequently, Lithuania’s environmental agency has spent 20 years suing the owners of the ineffective hydropower plant with an eye to restoring fish migration along one of Estonia’s largest salmon rivers. At the same time, Estonian colleagues confidently state that fish ladders do not work and full restoration of fish migration can only be achieved by dam removal. To date, roughly 40 dams have been demolished in Estonia for this purpose, mostly on the most promising salmon rivers.

Many aspects of river restoration experience in this small nation can serve as an important lesson for Ukraine and other countries preparing to join the European Union, as they too will have to comply with the Nature Restoration Law and other EU environmental directives.

Ukrainian rivers

On the penultimate day of the conference, a session on the restoration of large ecosystems took place, including two reports on Ukraine. Although the organizers discounted registration fees for Ukrainian participants by two-thirds and emphasized the importance of this topic in every possible way, Estonia’s distance from Ukraine and the war meant these were the only reports from Ukraine at the entire huge conference and those focused on the restoration of the Danube and Dnipro river ecosystems.

Mikhail Nesterenko of Rewilding Ukraine explored restoration of the natural dynamics of water exchange and biodiversity in estuary lakes Kartal and Katlabukh in the Danube Delta. Restoration of natural ecosystem processes also decreases salinization and improves water quality, contributing to improved living conditions and economic indicators for local residents.

UWEC Work Group expert Eugene Simonov presented a report on possibilities and organizational needs for restoration of Lower Dnipro River ecosystems in the context of implementing European legislation on ecosystem restoration. He described various post-war development scenarios offered by Ukrhydroenergo, Russian occupation authorities, and various research and public organizations. The process of restoring natural floodplain ecosystems at the site of the Kakhovka Reservoir and a complex of scientific, economic, and socio-political measures necessary to ensure it were analyzed in detail.

Eugene Simonov’s presentation:

The event’s expert participants were keenly interested in the option of using standard field methods, such as camera traps and drone observations, in the area around Kakhovka. The use of drones for non-military purposes is, of course, strictly prohibited along the line of contact at the front line.

In response to the question of what assistance was needed from those gathered, the speaker asked the international community of experts in the field of ecosystem restoration for assistance in assessing prospects for restoring ecosystem functions as well as assistance in interpreting and using European laws and programs in order to position restoration of the Lower Dnipro as a long-term priority project during Ukraine’s accession to the European Union.

Restoring natural ecosystems along a 250-km stretch of the Lower Dnipro could become the largest freshwater ecosystem restoration project in Europe and possibly serve as a decisive contribution by Ukraine to meeting EU commitments to restore rivers to their natural state by 2030.

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Main image: Discussion partners. Right to left: geobotanist Anna Kuzemko, marine biologist Halina Minicheva, environmentalist Viktor Karamushka, hydrologist Oksana Hulyaeva. Source: conference recording