Eugene Simonov

Oil and its derivatives occur naturally in the sea, as do microorganisms that can absorb and process these substances. But human activity releases petroleum products into seawater in such quantities that nature cannot cope, and the pollution causes chronic suppression or catastrophic upheavals in local marine and coastal ecosystems. Oil spills are also very dangerous for humans, affecting both health and local economies.

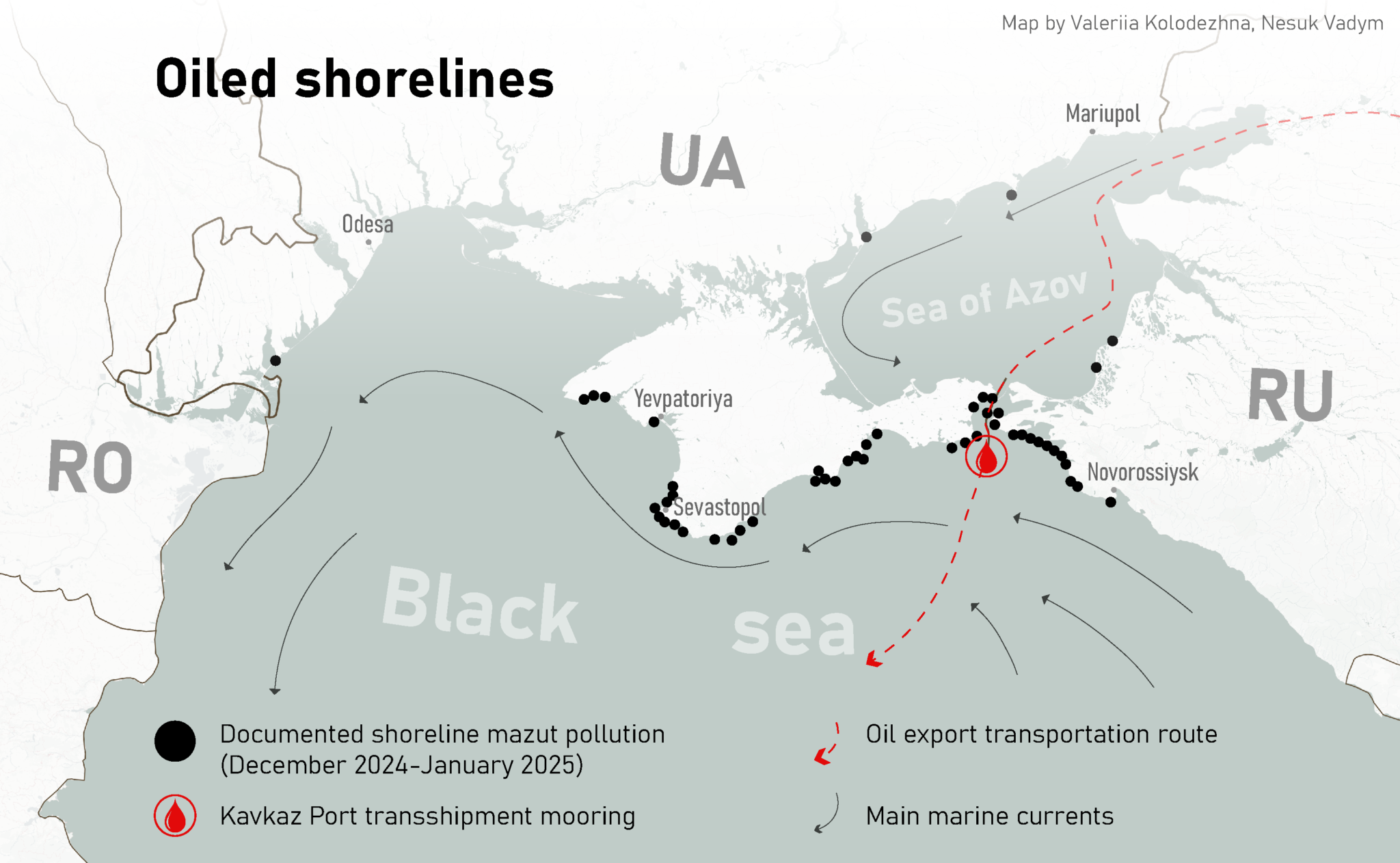

UWEC’s earlier article in this series covered oil pollution in the Azov-Black Sea basin, oil spills from tanker accidents, and the connection between the December 2024 disaster and Russia’s “shadow fleet” of ships exporting oil and oil products in defiance of sanctions. This second article covers the impact of the heavy fuel oil spill on animals and ecosystems in the region, as well as the disaster’s rapid spread to new coastal areas.

Mazut is hazardous to health

The December spill is largely mazut (a heavy fuel oil (HFO) produced in Russia), a thick and viscous blend of many substances that form as a residual product of oil refining (cracking) and which poses a serious threat to the health of both humans and animals.

According to Russia’s Federal Service for Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (“Rospotrebnadzor”), mazut is considered a persistent pollutant that mixes paraffinic, olefinic and aromatic hydrocarbons. This includes polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, benzopyrene, petroleum resins, asphaltenes, carbenes, carboids and other organic compounds which may contain iron, manganese, nickel, vanadium and other metals. The composition of a particular mazut product varies widely depending on the original grade of oil and the refining process.

Despite claims by Russian rescuers that the tankers were carrying M-100 HFO, the exact composition of the products that spilled during the tanker sinkings in December is unknown and continues to be a source of controversy over two months after the accident.

According to numerous testimonies, the spilled oil products contained an unusually large amount of polycyclic aromatic substances, emitting an atypical odor as mazut goes. In particular, participants in clean-up efforts reported that during work in many areas along the coast, the air was so saturated with oil vapors that people experienced dizziness and weakness. Medical experts commented that mazut contains many known carcinogens and increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Inhalation of mazut vapors can cause irritation of the respiratory tract, coughing and shortness of breath and can lead to bronchitis, pneumonia and other respiratory diseases. Direct contact with this petroleum product can lead to dermatitis, eczema and other skin problems. Some mazut components have neurotoxic properties that can manifest as headaches, dizziness and general weakness. Mazut absorption by humans and animals through skin, water or food can cause poisoning, digestive disorders, impaired coordination, weakness and even death.

Official reports noted that by February 7 almost 300 participants in beach cleanup had sought medical help, at least nine of whom were hospitalized. One minor student died after helping cleanup a beach, possibly from exacerbation of bronchial asthma, but also possibly from overfatigue. Another risk group is residents living near areas where the sand or soil mazut mixture collected along the coast is being stored and processed. For example, residents of the Voskresensky farm near Anapa, where sand from the pollution zone is kept at a “temporary accumulation site,” complained of headaches, coughing and high blood pressure.

Silent victims and the spill’s environmental consequences

As dangerous as it is for humans, for animals it is even worse. Zoologist Pavel Goldin noted that waterfowl and semi-aquatic birds have suffered en masse from the December mazut spill. They become covered in the sticky substance, their feathers stick together, preventing them from flying and disrupted thermoregulation causes birds to freeze. In addition, in using their beaks to try to clean their plumage, birds ingest mazut, leading to acute poisoning and mass mortality among birds. Svetlana Smirnova, Chairperson of the Krasnodar Branch of the Russian Ornithological Society, explained, “Substances in mazut ingested by birds negatively affect liver, kidney and pulmonary function.”

85% of bird victims of the spill to date are great-crested grebes (Podiceps cristatus), but other species of grebes, gulls, European shags (Phalacrocorax aristotelis), European cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), loons, swans, several species of ducks and other waterfowl and fish-eating birds also suffered. Among Red Book of Russia species affected by the spill, Arctic loons (Gavia arctica) have suffered the most; the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) states that the largest threat to this species is the issue of oil spills contaminating their overwintering habitats.

It is not possible to accurately calculate the number of birds that have died as a result of the spill, since only a small percentage of affected sea animals are recovered by rescuers, dead or alive. It is thought that after the similar but much smaller spill in 2007, 30,000 birds died. According to the Ministry of Emergency Services’s operational headquarters, at the end of January, 336 birds contaminated with mazut had been collected in Krasnodar province. 3,166 were captured alive and sent for rehabilitation, but less than 500 birds ultimately survived. Official statistics for Crimea have not been made public. The number of affected birds may increase significantly when the spring bird migration north gets underway. In general, fewer than 10% of birds affected by oil products survive rescue attempts in oil spill cleanups around the world.

Even less is known at this time about how fish are affected. AzNIIRKH (Azov Research Institute of Fisheries), a regional center for fisheries science, previously reported that fish eggs begin to be killed at concentrations of oil products of approximately 0.000006 mg/l of water. Fish fry are approximately one order of magnitude more resistant than eggs, and adult fish can withstand even higher concentrations. The toxic impacts of oil on adult fish is evident at concentrations of oil products of 0.01-0.1 mg/l of water, affecting their physiology, nutrition, reproduction, and other biological processes. Depending on the duration and scale of the pollution, a wide range of damaging effects can be observed: behavioral anomalies and the death of organisms in the water column at the initial stages of a spill to structural and functional reorganizations in populations and communities with chronic exposure in coastal benthic ecosystems.

Before the Federal Fisheries Agency had time to express cautious optimism and announce that commercial fisheries were unharmed and catch was fit for consumption, a large school of dead European anchovy washed ashore in Sevastopol on January 14, coinciding with the timing of the oil spill and when fishing was underway. In January 2025, commercial fish harvests decreased relative to January 2024, which may also be due to the disaster’s consequences.

Marine biologist and NGO Ekodiya climate expert, Sofya Sadugorska told UWEC that spills of any oil products result in an oxygen-impermeable film at the sea’s surface, preventing oxygen exchange and affecting respiration in aquatic organisms. In addition, oil products are toxic to sea inhabitants, especially to neuston, microscopic organisms that inhabit the water’s thin surface layer. This water acts as an “incubator” for many pre-adult aquatic organisms. Pollution and blockage of gas exchange on the surface and for neuston can lead to significant changes in food chains and disruption of the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

When mazut settles on the seabed, it kills seafloor fauna and flora, explains Goldin. For example, there are many endemic species of goby, a food source for dolphins, in the Black and Azov seas. Mazut components can also accumulate in shellfish and other bottom-dwelling organisms lucky enough not to die immediately after the spill. Consequently, mazut toxicity can affect entire food chains, at the top of which are cetaceans and humans.

Goldin also notes that contact with a large oil spill may cause acute intoxication and skin and mucous membrane burns in dolphins. The worst consequences occur much later as a result of accumulated toxins causing significant weakening of cetacean immune systems, development of various diseases, and infectious disease outbreaks. From December 15 to February 7, more than 80 dead dolphins and Azov-Black Sea porpoises (Azovkas) have been recorded on the coast of Krasnodar province and the Crimean peninsula. A possible connection between their deaths and the mazut spill was officially recognized by the Federal Fisheries Agency. However, as of the end of February, not a single report on autopsies and examinations of the causes of death of cetaceans has been made public, limiting public understanding of the specific causes of death for porpoises, mortality which is occurring more frequently than on average in previous winters.

Overall, the history of other spills in Europe shows that a December mazut spill is less damaging to marine biota. Most species do not actively reproduce or migrate along the coast in December, and the storm season facilitates rapid cleanup of marine habitats (but increases coastal pollution and complicates cleanup there). A similar spill in spring or summer could have much greater immediate consequences for marine life.

Scale of the catastrophe grows steadily

An important characteristic of mazut, which, according to official data, constituted the main cargo of the damaged tankers, is that on average its density is similar to that of water, density which changes with temperature. At the same time, mazut is a rather arbitrary mixture of many chemical substances that can exhibit different characteristics in sea water. Prior to the spill, the mazut was probably heated to facilitate transshipment to another vessel. Once it entered the water, it first floated on the surface and then quickly cooled, light fractions evaporated, and some components dissolved in water, while others oxidized, etc. As a result, a portion of this mass formed films and accumulations on the surface, some clots entered the water column and others settled to the bottom. Thus, the spread of such a contaminant is quite difficult to predict, given how temperature, winds and currents influence mazut dispersal.

By early February 2025, mazut had reached coasts far from the site where the tankers broke apart. It traveled west to the Danube Delta in the Odesa region (600 km) to occupied Berdyansk in the north, to Zaporizhzhya region in Ukraine (170 km), and southeast to the Gelendzhik resort town in Russia’s Krasnodar province (160 km). Birds coated with mazut were also observed in more distant locations, including Adler, Imereti Lowlands, and even Batumi (Georgia).

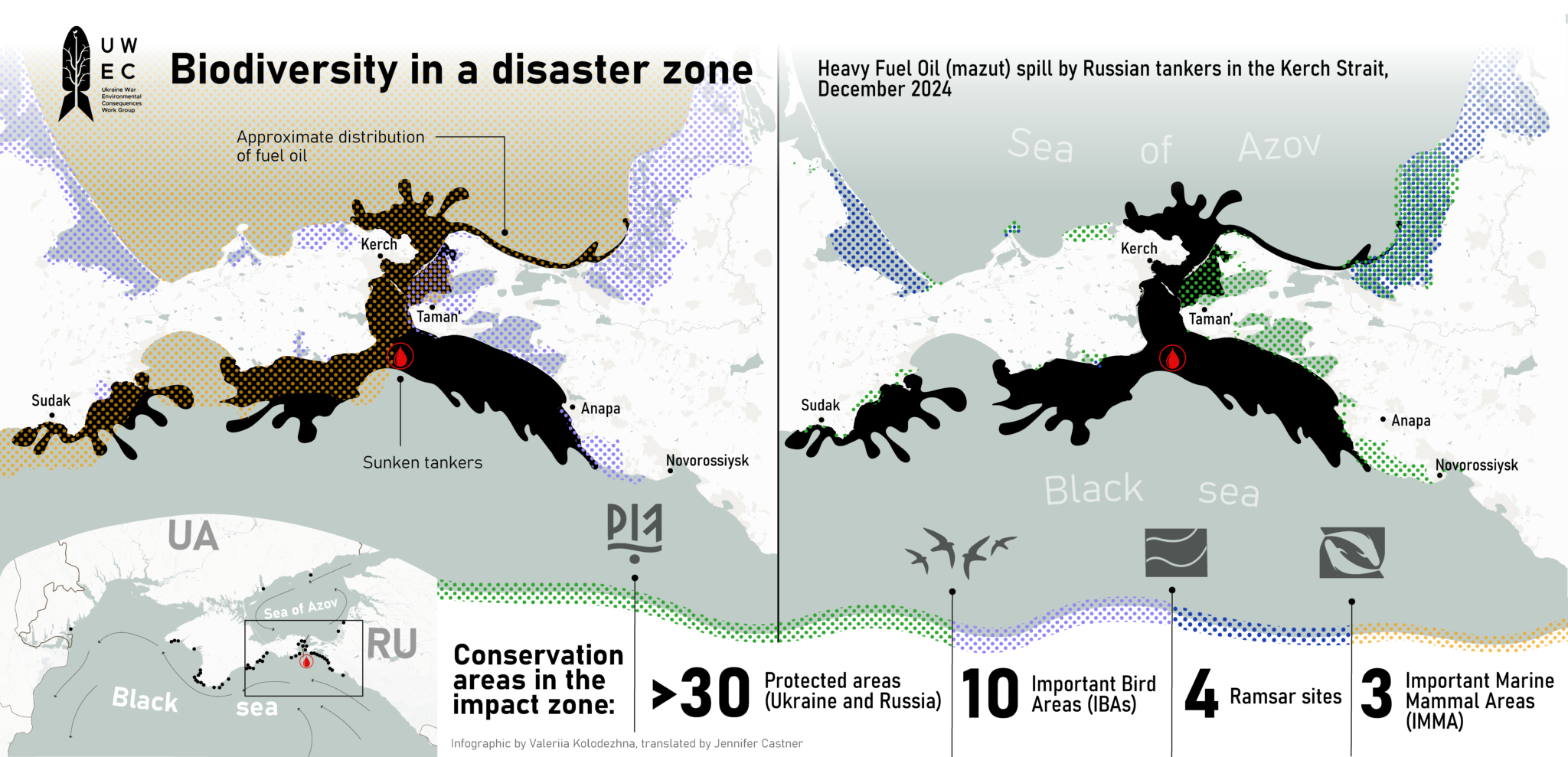

Water areas and coastlines affected or threatened by the mazut pollution include extremely valuable ecosystems, protected areas, and major tourist and recreational centers. The Kerch Strait itself is critical habitat for all three Black Sea cetacean species: common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), “Azovka” harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) and common dolphin (Delphinus delphis). According to Dmitry Glazov, executive director of the Marine Mammal Council, their migration routes pass through the strait, and breeding season feeding grounds are in the area as well. The Kerch Strait and Taman Bay are included in IUCN’s list of Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMA). In sum, the mazut spill has affected at least five IMMAs in the Azov-Black Sea basin.

Zaporizhzhya-Tamansky Nature Reserve is also located in Taman Bay, through which up to two million waterfowl migrate and many hundreds of thousands of birds overwinter. In 2007, a significant proportion of the 30,000 birds that perished in that earlier mazut spill died in or near this protected area. In mid-January 2025, mazut pollution covered the southwestern shore of Taman Bay, and it is possible that it will spread further into the protected area. Environmentalists have repeatedly asked the authorities to block the entrance to the bay using oil-spill booms and mazut-trapping nets, or to at least stop oil from reaching the main coastal reed beds sheltering birds.

Consequences of the catastrophe for ecosystems in Ukraine

The greatest pollution of the Ukrainian coastline occurred on the occupied Crimean Peninsula, Ukraine’s most valuable landscapes in species diversity terms. It is noteworthy that almost the entire coastline of the Kerch Peninsula and a significant part of Ukraine’s southern coastline of Crimea include sites in the Emerald Network, a register of the most valuable habitats in Europe in need of protection. The Ukrainian side of the Kerch Strait was nominated for inclusion in the Emerald Network in 2019, in other words, after the peninsula was annexed by Russia.

Learn more: Emerald network in Ukraine

The entire Crimean shoreline along the Kerch Strait suffers from ongoing and intensive emissions of mazut at present. Also threatened is the area around Kazantipsky Nature Reserve on the Azov coast of the Kerch Peninsula. There the occupying authorities have given permission to store and process mazut-contaminated materials on a completely unsuitable site, one that was previously intended for construction of the planned Crimean Nuclear Power Plant.

The December 2024 shipwrecks occurred opposite Cape Takil, at the peninsula’s southeastern tip, where a landscape-recreational refuge of the same name is located. Satellite images showed a large area of spilled oil and fouled shorelines here as early as late December. Further west on the Crimean coast, Opuksky Nature Reserve and the sea surrounding it have been protected since 1972 and is known as the Coastal Aquatic Complex at Cape Opuk and the Elken-Kaya Islands. This protected area was created to protect marine and migratory fish, including sturgeons. It is also recognized as a Wetland of International Importance and is included in the Ramsar Convention list. On January 4, 18 kilometers of the reserve’s shoreline were coated with mazut for the first time, and after that cleanup, mazut has washed ashore several more times. Another IMMA, Karadag and Opuk IMMA stretches along the coast from Cape Opuk to Karadag Nature Reserve and is critical habitat for bottlenose dolphins.

Further west, there are many protected areas on Crimea’s southern polluted coastline between Cape Opuk and Cape Tarkhankut: 23 regional protected areas, nine national refuges of national significance and two nature reserves. Many of these protected areas have been affected. Cleaning up clots of mazut along these jagged rocky shorelines is an almost hopeless task. Shallow waters with uneven rocky bottoms and covered with dense thickets of large algae—typical habitat along the Crimean coast—can trap settled mazut in the long-term, poisoning local biota and serving as a source of repeated oil slicks and fouling shorelines in the future.

Also heavily polluted are waters along the coast of southwestern Crimea, including the Balaklava and Southern Crimea IMMA, important habitat for all three Black Sea cetacean species.

Information about specific mazut pollution in Crimea is quite scarce, given that occupation authorities are trying to put a positive spin on the situation and regularly talk about the pristine purity of one or another popular shoreline. The fact is that they are justifiably afraid of disrupting the summer resort season and/or fear reprimands from their higher ups.

Six weeks after the spill, occupying leader of the Republic of Crimea, Sergei Aksyonov’s office released a decree on January 30 informing residents that an additional six districts were included in the emergency zone and that the zone currently includes the Kerch, Feodosia, Sudak, Saki, Yevpatoriya metropolitan areas, as well as Leninsky, Saksky, and Chernomorsky districts. Sevastopol is also now included. In other words, only two communities—Alushta and Yalta—have not yet been declared part of the emergency area. There are probably two reasons for such a belated expansion of the emergency zone: extensive new contamination with oil products along the entire coast at the end of January and the opportunity to use emergency declarations in order to obtain federal money with weak oversight.

The intensity of spill pollution was also quite significant at the western end of the peninsula near Cape Tarkhankut and Donuzlav Bay, an area that is key habitat for wintering and migratory birds. The entire Sevastopol shoreline was also heavily fouled with mazut.

In addition to Crimea, Ukraine’s Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources reported mazut pollution around December 20 along the Sea of Azov coastline at Priazovsky National Park in the Zaporizhzhya region in the coastal zone between Stepanovskaya Spit landscape refuge and the border with Kherson region, including parts of the Fedotova Spit and Peresyp Spit landscape refuges. From January 11 to 14, the occupation administration of the Zaporizhzhya region organized a mazut cleanup on the shores of both the national park and Berdyansk Spit, but a new batch of mazut washed ashore near Berdyansk on February 1.

Head of Tuzlovsky Liman Nature Park’s science department Ivan Rusev reported that as of February 1, the farthest extent of mazut pollution from the disaster site occurred in the Odesa region on a sand spit near the Katranka recreation area, not far from the Danube Biosphere Reserve and nature park. According to him, oil-contaminated birds first appeared in the park in early January, but they could not be saved. The oil spill itself was small and consisted of fairly solid small clots of oil, pollution which has to be collected by hand.

The border between Romania and Ukraine travels through the Danube Delta, so it is possible that oil products will reach the Romanian part of Danube Delta Nature Reserve in the near future. The spill has most likely already affected waters in another IMMA “Kaliakra to the Danube Delta”, which stretches from the northern edge of the Danube Delta to Cape Kaliakra in Bulgaria and is habitat for common dolphins and Azov porpoises in the summer.

In accordance with the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the following “ecologically or biologically significant marine areas” (EBSAs) have been identified in areas of the Azov-Black Sea basin that are affected by oil pollution: EBSAs Danube Delta, Zernov’s Phyllophora Field and Balaklava in Ukraine, with Taman Bay and the Kerch Strait EBSA on the Ukraine-Russia border, as well as the Kuban Delta and Northern Caucasus Black Sea Coast in Krasnodar province (see the CBD’s official map). The latter EBSA, along the shores of Anapa, suffered the most from pollution.

Russia’s spill epicenter and delayed efforts to shield the coastline

In Russia’s Krasnodar province, Anapa Persyp protected area was hit the hardest, along with beaches and spits of resort town Anapa and the adjacent Temryuk district. Most of the photos and videos showing apocalyptic pictures of the shores covered with a continuous carpet of mazut were taken here.

In addition to multiple instances of oil pollution, beaches and protected areas in Anapa have also suffered the removal of huge masses of oil-contaminated sand as a result of generous state payments for their removal and storage at temporary storage sites, regardless of the proportion of mazut in the removed material. By the end of January, only 30-50 cm of sand remained atop the bedrock on some beaches. Experts believe that this practice will cause rapid coastal erosion and destruction of the existing near-water infrastructure.

At the end of January, the authorities began to create a ditch and rampart along the water’s edge stretching 42 km from Anapa’s central beach to the village of Veselovka in Temryuk district. A polypropylene net is being laid along the rampart, which should protect the structure from being washed away by storms and is a sort of filter, capturing even small particles of mazut.

Director of Anapa Resorts Nikolai Zalivin stated that the main purpose of the two-meter rampart is to prevent new oil product pollution on the remaining 10-12 m of beach width.

Three lines of protective barrier were also created on the spit between the reservoir and the sea in order to protect Solyonoye Lake Nature Monument: a drainage channel, sand rampart reinforced with a net and an additional line of sandbags where sea waves could reach the lake. It is understood that all these engineering structures constitute additional violations of the territory’s natural character and that their construction is a major disturbance factor, for example, for wintering birds.

Pollution is gradually spreading to other resort areas in Krasnodar province on the Black Sea coast. According to the official map, there are up to 20 protected areas along the coast here.

Among federal protected areas, east of Anapa the spill reached Utrish Nature Reserve, the staff of which has repeatedly reported that they “cleaned everything up quickly” and “there have been no further mazut impacts.” The grounds of the reserve are closed to visitors, but the surrounding area that is open to the public is heavily fouled, and birds covered in mazut are regularly found on the shoreline.

The last Russian protected area found to have been contaminated with mazut is Priazovsky Nature Refuge in the Kuban Delta on the Sea of Azov. There more than 1,350 kg of seaweed, sand and stones contaminated with mazut were collected near the villages of Kuchugury and Achuevo January 20-24. Situated along a flyway, over 200 species of birds stopover in Priazovsky Nature Refuge during migration. Sea currents and storm surges, especially frequent in winter, could mean that the rest of the delta may also end up in the “risk zone”.

The Sea of Azov is designated as an IMMA in recognition of its role as the most important breeding ground for Azov porpoise. At the same time, judging by the breadth of coastal locations where the mazut is turning up, the mazut spill has probably affected the entire southern part of the Sea of Azov.

Beach holidays with a dash of mazut

Government authorities, business, the press and the Russian public are very concerned about the safety of beach holidays this year. Russians are not as eagerly awaited at foreign resorts as they once were, and, given the weak ruble, vacations abroad have become more costly. Moreover, since the war’s beginning, employees in government, law enforcement and defense have been prohibited from leaving the Russian Federation. Despite Russia being washed by three oceans and a dozen seas, beach resorts are found mainly in the Azov-Black Sea basin, because other seas are very cold. In the last three years, Russians have even vacationed in areas of the Black Sea coast that are adjacent to military facilities regularly subjected to shelling by the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

The Russian official press quotes regional officials who remain optimistic about the prospects for vacationing at Black Sea resorts this year. Until mid-January officials unanimously promised that they would “prepare Anapa for the resort season,” but by February most forecasters were saying that the resort season in Anapa and Kerch is ruined, although other places are mostly safe for holiday-goers. The Travel Industry Association even published a combination map showing both military shelling risk and mazut pollution on the coast in order to attract vacationers to Black Sea resorts.

The ostentatious optimism strongly contradicts experience, facts and scientific forecasts. Even if the mazut that washed ashore in December could be removed to produce safe and clean beach conditions, a significant quantity of mazut and other oil products have settled on the seafloor along the coast and will reappear in the future one way or another. When water temperatures warm in April, Minister of Natural Resources Alexander Kozlov and his experts expect a significant amount of mazut to resurface, creating a new wave of pollution both in Anapa and on other coasts in Kuban and Crimea.

Other experts believe that it is not rising temperature that raises mazut to the surface but storms. Mazut will continue to be regularly washed ashore with each storm, although the amount will gradually decrease. Spilled oil derivatives are found mainly in relatively shallow areas. In the northern Black Sea, wave action can be felt up to 100 meters deep, so almost all of the spilled mazut remains in the reach of waves. This means that it will emerge again and again, regardless of water temperature. The exception is probably along the southern coast of Crimea, where the shelf drops off greatly right at the shoreline and sunken mazut has no chance of re-emerging. But springtime water currents may deliver huge amounts of mazut that first rose to the surface elsewhere.

The expanding geographical creep of mazut to new shores is also inevitable. Some experts, including Viktor Danilov-Danilyan, scientific director of Moscow’s Institute of Water Problems, concede the likelihood of oil products turning up on the shores of other Black Sea nations, such as Georgia, Bulgaria and Turkey, which seems more and more likely as events unfold.

Those who consider the oil spill as already in the past are hopeless optimists. Experts predict that it will take between two and 20 years to overcome the consequences of this disaster.

All eyes are on microbes… Recovery is likely to require decades

Volunteers from all over the country arrived at their own risk to clean up the mazut and save birds from the first days of the spill. They drew media attention to government inaction, but still did not receive timely assistance or support by government agencies. Rospotrebnadzor’s guidelines for safe oil volunteer cleanup were released 45 days after the accident and do not contain a single reference to specific studies on the health consequences of mazut toxicity.

Anyone commenting on the disaster never ceases to be amazed at the incompetence, indifference and impotence of the Russian government that is being demonstrated during the “spill cleanup”. The entire state machine has seemingly fallen into a stupor, as if it had never seen a mazut spill. Ten days passed before the government declared a national state of emergency – the very time window when something could still have been done to reduce the scale of the spill’s consequences.

Additionally, the possible impacts and measures required for addressing them have been well studied thanks to the Volgoneft-139 tanker accident in 2007 in the same Kerch Strait. At the same time, federal Marine Rescue Service experts brazenly claim that the December accident is “the world’s first mazut accident” in an attempt to justify the lack of equipment on hand, established procedures for spill cleanup, or capacity for safe disposal of mazut and contaminated sand along the coast. In reality, marine mazut pollution has been a common occurrence since the Soviet era, and a number of specific cleanup solutions and technologies exist.

Russia’s federal Emergency Services Minister candidly admitted on December 28 that “as far as the water aspect is concerned, it’s a complete unknown.” Neither that agency nor the Government Commission for Oil Spill Cleanup know what to do with the sunken mazut, and neither entity has the necessary specialists or equipment to monitor and cleanup such spills. 50 days after the accident, three halves of the sunken tankers containing mazut remain on the seabed, and these government organizations lack the skills and technology to pump it out or raise the vessels, as well as being unwilling to request assistance from countries that do have such capabilities.

On the eve of the new year, the Ministry of Emergency Services released to the press a video demonstrating the government’s technological capacity for monitoring the situation: a rope tied to a workout weight, which they then dragged along the seafloor on the shoreline in order to judge the location and amount of mazut that has settled there.

Considering all the experience and technological capabilities the “great energy superpower” has already demonstrated in the process of responding to the mazut spill, there is no doubt that the leading hope for disaster cleanup is microorganisms that, though slowly and reluctantly, both break down and harden clots of mazut, turning thicker fractions into inert solid clumps similar to stones. In that case, 10-20 years is a realistic timeframe to fully address the disaster’s consequences.

As the flooding of pollutants into the Black Sea following the sabotage of Kakhovka dam has shown, most components and processes in marine ecosystems are generally capable of rapid recovery in a year or two following catastrophic events. Vulnerable species, coastal ecosystems and the tourism and recreational industries will take much longer to overcome the consequences.

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Main image: Net fence to capture mazut in Opuksky Nature Reserve, January 2025. Source: Ecologist Zhora Kavanosyan Telegram channel