By Oleksii Vasyliuk and Vadim Kiriliuk

This article discusses the current discourse on border barriers and related environmental issues. It explores the high-profile case of a wall built by Poland across a transboundary World Heritage property to control the inflow of migrants from Belarus. Given the accelerating development of a new Iron Curtain, active dialogue between experts in ecology and border security is essential to prevent damage to natural ecosystems.

Border barriers and nature

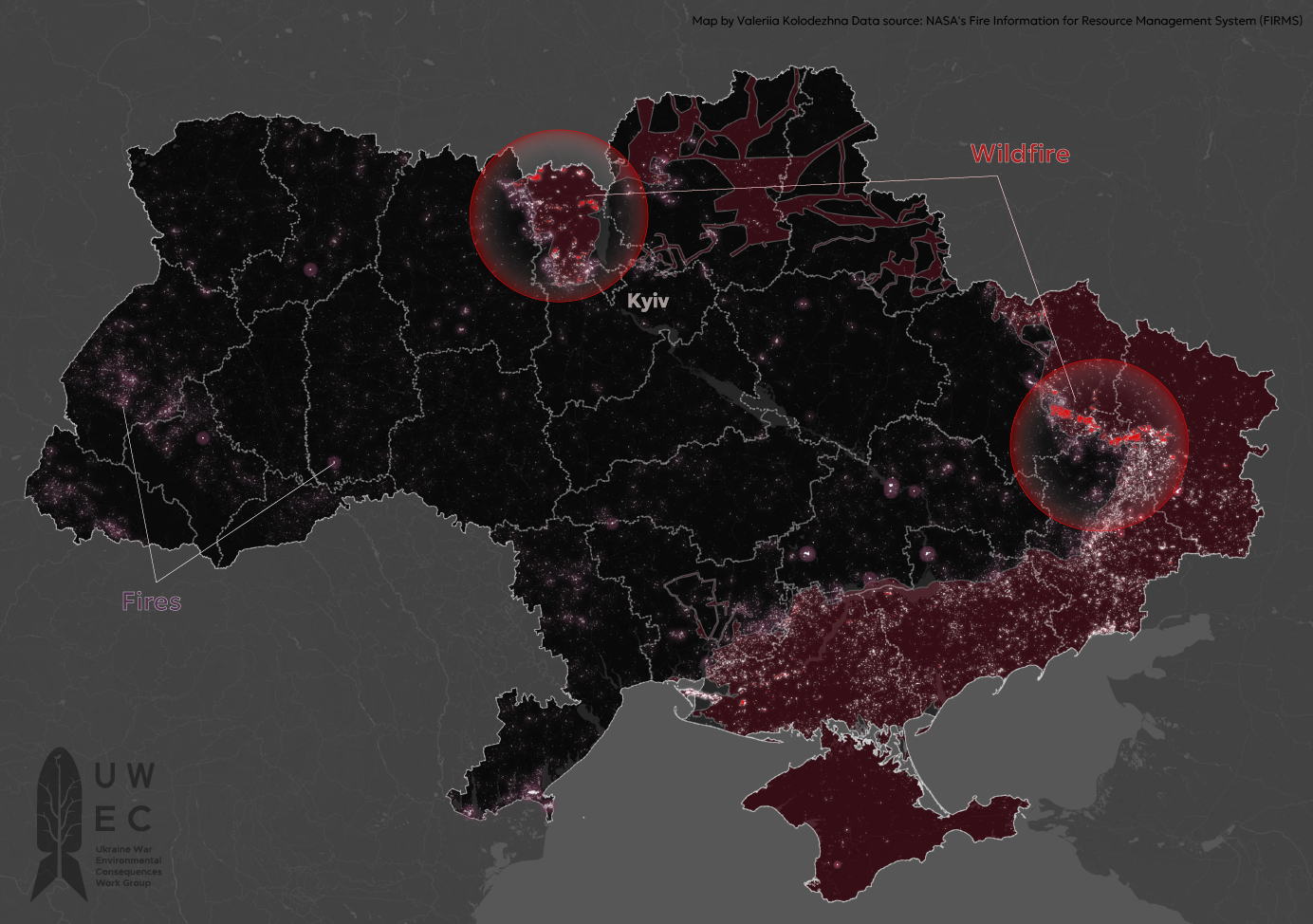

Decisions made during crises, dynamic geopolitical situations, or, even more so, during wartime often fail to consider wildlife conservation. In most modern cases, crisis decisions to build walls to strengthen a state border (for example to address illegal migration) occur in more developed and democratic nations. In the recent past, the USSR was a champion of fence-building to prevent not only penetration by saboteurs, but also the mass exodus of its own citizens. In general in the last century, growing confrontation between nations has always been accompanied by the creation of barriers and fortified areas along borders.

A well-known recent example is a wall built by the US for hundreds of kilometers along the US-Mexico border (current length is 1053 km) to create a barrier against illegal migrants. Several thousand scientists from around the world have signed a petition against the expansion of this wall.

And, of course, the best known example in global history is the Great Wall of China, known to every school child and registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Little is said about its environmental consequences despite its direct impacts on the ecosystem over the last two thousand years.

The Russian-Ukrainian war, as the most acute crisis of this century in Europe, has provoked an unprecedented wave of wall building in Europe. Poland and Belarus have already taken action. Russian-backed separatist enclaves, such as South Ossetia, are actively manipulating border fences to expand their sphere of control. Earlier, Ukraine repeatedly stated its intention to implement a “wall” project (in particular, in its eastern regions) designed to harden its border with Russia. Finland has announced plans to build a wall with Russia, as has Lithuania with Belarus.

In the era of a rising new Iron Curtain, intractable questions arise. How do countries consider and balance the needs of nature protection and national security? Is it possible to have a productive dialogue between environmentalists on the one hand and border services on the other? What alternative border protection options exist and what environmental risks do they entail? Is it possible to objectively assess environmental impacts when establishing military installations? What do the age-old experiences of border fences and border zones in the USSR and other countries teach environmentalists?

Our working group begins this difficult conversation in the hope of being heard by different stakeholders and institutions for developing optimal solutions. In an era when the armies of the world are beginning to intentionally track their carbon footprint, governments must also think about biodiversity conservation in the course of military activities. After all, the world has entered a period of extreme turbulence – military, socio-political, climatic. And the worst thing politicians can do is to use national security slogans to postpone environmental issues until an era of stability far into the future. Today’s climate change crisis puts humanity itself on the brink of survival and thus requires equally urgent solutions.

A little theory – a definition of landscape fragmentation

Fragmentation of natural landscapes is one of five globally recognized causes of ecosystem destruction. Separation of natural areas by man-made barriers (roads and railways, fences, clearings, agricultural landscapes, and, ultimately, cities) significantly complicates the movement of terrestrial animals that is necessary for their normal existence. For some species and populations this refers to regular (seasonal) purposeful movements across hundreds of kilometers (for example, reindeer or many species of migratory birds). Many ungulates and predators depend on seasonal migrations and daily movements in search of food and shelter within rather large individual habitats. For many species, maintaining the viability of even one pair or, even more so, a stable population, requires large areas, often to the extent that no such landscapes remain in European countries. Natural barriers should not stop animals when their instincts tell them to move. For example, this is why many wild animals are good swimmers, even when they are not primarily aquatic. For many species, human-made barriers can often be insurmountable.

In the long term, the ability of a species to move around the landscape is critical: without genetic exchange among individuals, isolated populations of a species degenerate after several generations and, as a result, often disappear altogether.

In an era of rapid climate change, the ability of animals to move from areas of increasing climate stress to landscapes with more favorable and familiar conditions also becomes especially important.

As landscape fragmentation occurs, movement restrictions and isolation lead to a decreasing number of species. Today, the survival of remaining large mammals is supported by specific conservation measures in densely populated Europe, but the appearance of new artificial barriers may put them at the brink of extinction.

Nevertheless, some animals are able to adapt to new conditions and survive alongside their human neighbors: using clearings and roads at dusk and even finding sustenance in agricultural landscapes. Moreover, man-made bridges over rivers are quite helpful for the migration and dispersal of terrestrial animals, as is, for example, a network of forest belts in the forest-steppe zone in southern Ukraine.

Environmental science includes the concept of landscape permeability for animals; consider the behavior of rabbits in the garden or roe deer or foxes in a cultivated field. Crossing man-made landscapes can be simple for many species, even large mammals, especially birds. The same cannot be said for impervious borders or other extended fences.

A solid high wall, stretching for hundreds of kilometers, can become an insurmountable barrier for any terrestrial fauna or plants that depend on wind to spread their seeds. Moreover, natural features shrink in number when a small country starts building a wall. Animals and plants are destroyed during initial construction. For example, during construction of the Polish wall, a strip of forest 200 meters wide was cleared along the border. In addition, animals’ ability to penetrate from the outside is sharply reduced; populations that find themselves in isolation may be on a path to degeneration.

It is for these reasons that researchers and environmentalists criticize state moves toward planning each new boundary wall, but, in the end, these barriers are usually erected without incorporating the recommendations of specialists.

It should also be noted that highways and railways, with or without vertical barriers, are in many cases much deadlier than border fences. Entire populations of small animals – amphibians, reptiles, small mammals – simply die out along such roads if animals have access to the roadway. Many large animals also die – moose, significant numbers of dispersing young foxes, hedgehogs, and beavers. Birds of prey also die in great numbers when landing on the road to feed on the road’s earlier victims. This is a sore subject, and it is worth a separate discussion.

Fence through Białowieża Forest

In March 2022 in its report to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the government of Poland reported:

“Since August 2021, Belarusian state services have been bringing groups of thousands of migrants from the Middle East into the direct border zone with Poland, in the Białowieża Forest property area, and forcing them to illegally cross the Polish state border. This poses a serious threat to the security of the state and Białowieża Forest World Heritage Site. As a result, the Polish Government and Parliament decided that a barrier must be built along the state border with the Republic of Belarus. The planned construction of the border barrier will be implemented in accordance with the Act of 29 October 2021 ‘On the construction of state border security’ (Journal of Laws of 2021, item 1992).”

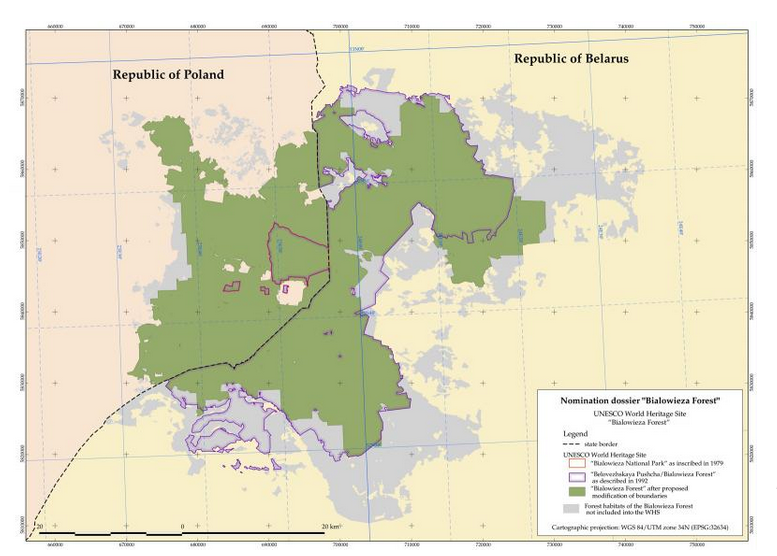

Poland’s resulting wall along the border forms a barrier to illegal migrants attempting to enter the European Union from Belarus. The wall divides the transnational Białowieża Forest WH, one of Europe’s most important protected areas, into two parts. At an installed height of 5.5 meters, the barrier stretches over 186 km. Such ambitious projects can indeed form a barrier for illegal migrants and subversive groups, but are also a significant threat to wildlife.

Białowieża Forest World Heritage Site is a transboundary site and it is specifically thanks to its location on the periphery of the two bordering countries that undisturbed wilderness is preserved here. Its integrity is the foundation of a truly important protected area.

As conceived by UNESCO, the creation of transboundary protected areas is an important measure not only for international cooperation (lacking today due to the current political situation), but, above all, for greater conservation of nature.

In an interview with Reuters, Guy Debonnet, chief of the Natural Heritage Unit at UNESCO’s World Heritage Center, said Poland had to demonstrate that the wall would have no negative impact on the protected site: “Poland should not move forward with this before we have the necessary assurances and our advisory body for natural heritage is convinced this can be done without impacting the outstanding universal value of the World Heritage property,” he told Reuters.

According to Debonnet, ecological connectivity between the Polish and Belarusian parts of the forest was a key element when the World Heritage status was extended to Belarus in 1992.

According to the practices of the World Heritage Convention, any country that introduces significant alterations (e.g. an infrastructure project) to a World Heritage property is supposed to undertake a Heritage Impact Assessment and submit results to the World Heritage Center prior to project implementation. The Polish report to UNESCO promises “that environmental issues, including the welfare of animals and especially their migration needs, will be taken into account in the project …. Particular attention during the implementation of the project will be paid to border protected areas, and in particular to the transboundary World Heritage Site Białowieża Forest. In order to take care of the migration needs of wildlife, it will be equipped with special animal crossings to eliminate the barrier effect and the watercourses will not be fenced.” However, nothing in that report suggests that an environmental impact assessment took place, and similar concerns exist from the standpoint of EU legislation.

Over 1,800 scholars, environmentalists, and activists in Poland and other European Union countries signed a petition calling for a ban on building fences along the Belarusian-Polish border. In an open letter to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, First Deputy Frans Timmermans, and European Commissioner for Environment, Oceans, and Fisheries Virginius Sinkevičius, petitioners drew attention to the fact that no impact assessment related to Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park (a part of the Natura 2000 network) occurred during the planning process for the wall’s construction.

As elsewhere in the EU, and in accordance with EU directives “Directive 2009/147/EC on the conservation of wild birds” and “Directive 92/43/EC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora,” the Natura 2000 protected area network operates in Poland. This network requires impact assessments on the conservation value of any project undertaken on member sites in Poland. Each country is accountable to the EU, which finances Natura 2000, for the fulfillment of the ecosystem functions of such territories.

The letter’s authors worry that the fence’s construction will result in moving the Białowieża Forest World Heritage Site to the “List of WH in Danger.” This is a particular concern for Belarus, where Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park is included on the list as a transboundary extension of the Polish World Heritage property.

Along with the leadership of the Belarusian national park, five European organizations have submitted complaints about the border wall to the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. Their complaint awaits review today.

After provoking riots at the border in 2021, Belarusian authorities have now submitted complaints to UNESCO and several other international organizations that the construction of the wall harms the reserve’s wildlife. During a Belarusian Foreign Ministry press conference, Belarus National Commission on UNESCO Affairs Secretary Natalia Schasnovich reported that (31:39 in the video) in February-March 2022, the UNESCO World Heritage Center asked the Polish government to provide a detailed report and suspend construction until an environmental impact assessment was carried out. Belarusian officials confirm that this project was planned with neither an environmental impact assessment nor input from the Belarusian government.

Belarus not only spoke out against the fence’s construction at the state level, but the Belarusian State Control agency also announced calculated environmental damages in the amount of 52 million rubles (over 17 million Euro), and the Belarus Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection released a dramatic and disturbing video showing the harm to wildlife allegedly caused by such fences.

In addition, on 18 March 2022, a round table for state officials and administrators of academic institutions was held in Belarus dedicated to the topic of “Construction of artificial barriers in transboundary protected areas: real harm with imaginary benefits.” Among other statements, participants noted that demolition of a barbed wire barrier long ago erected along the Belarusian side of the border was planned, but not yet carried out. According to round table participants, creation of a new wall along the border will disrupt the migration routes of terrestrial mammals, and a concrete dam at the wall’s base will change the hydrological regime and result in wetland formation on the Belarusian side. Belarusian experts announced that the Polish fence project violates at least 8 international agreements.

Strengthening Belarus’ borders

However, the sincerity of Belarusian official statements is doubtful. It is more likely that the country’s dictatorial regime is using this environmental rhetoric as a smokescreen for other goals. This was clearly seen at the UN General Assembly meeting on 28 July 2022, when Belarus refused to support adoption of a historic resolution on the “human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.”

According to the UNGA meeting official coverage, “Belarus’s representative said that the country abstained because… recognizing a special category of human rights can only be done through a universal and legally binding instrument. Then she drew attention to the environmental and legal aspects of Poland’s construction of a barrier along its border with Belarus that is damaging the environment and urged Poland to dismantle the structure and restore the damage….Responding to her counterpart from Belarus, Poland’s representative explained that in 2021, Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko engineered a migration crisis, stranding thousands of migrants. This is the sole reason for the structure on Poland’s border, a situation Poland is closely monitoring. The fence on the Polish side includes 20 large animal crossings, she said, noting that waterways and marshes, among other areas, will not be fenced. The fence will be subject to electronic monitoring by Poland.”

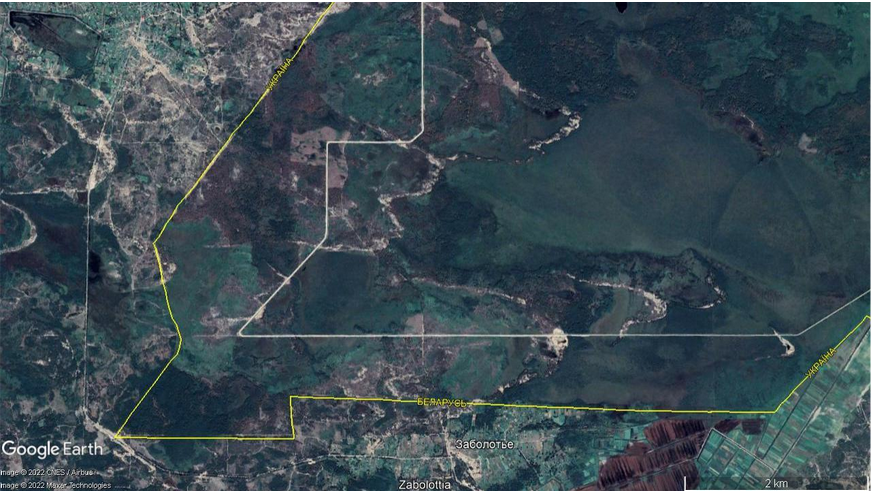

Belarus’s own history of border barriers is not at all an example to be followed, even as it convincingly criticizes Poland’s actions. Throughout May, June, and July 2022, Belarus’ armed forces actively built a network of fortifications along the border with Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania. They have also laid minefields, an obvious deadly threat to large animals, since at least 2018. Unfortunately, this immediately led to devastating consequences for nature. Because part of the Belarusian-Ukrainian border runs through very swampy terrain, Belarusian authorities have launched a program to build dikes in protected swamps. The world famous Olmansky Wetlands Refuge suffered damage as a result.

Belarus’ State Border Service is also implementing the Protection Line project, which will pass through 19 protected areas, including the same Belarusian Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park as well as Sorochansky Lakes, White Moss, and Braslav Lakes nature refuges.

It is also noteworthy that environmental NGOs were not able to critique construction of the barrier, given the fact that the majority of them were liquidated by the Belarusian government in 2021. Indeed, most environmental cooperation projects with the European Union in the Belarusian part of the Białowieża Forest WH property have been put on hold for the time being.

Greening the curtain?

Construction of a new Iron Curtain in Europe is becoming more and more certain, and, most likely, will be actively developed in the coming months and years. At the same time, the natural environment in states along boundary fences will certainly experience certain changes. On the one hand, wildlife movements will be limited, while on the other, wildlife will actively develop in little-visited border zones. Also, poorly selected construction materials and technologies for the barrier can result in changes in the hydrological regime. Prudent and environmentally responsible planning for additional border protection measures can significantly reduce and possibly minimize the negative impacts of new barriers.

In many cases, different technologies and management solutions that are more responsive to conservation needs and national security concerns can be proposed in place of extended impervious barriers.

It is often completely impractical to divide a protected area or even an unprotected wetland with a fence, because it is generally more effective to build barriers along the borders of developed areas, leaving impassable thickets and marshes between the fence and the border. Such an approach benefits the preservation of undisturbed landscapes and turns national border security into a useful conservation measure. Experts around the world are well aware of the example of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) along the 38th parallel between North Korea and the Republic of Korea. That zone is one of the most important nature islands on the Korean Peninsula and is an important migratory stopover for rare crane species.

In most cases, additional environmental and other measures can be envisioned to radically reduce environmental impact, for example, by eliminating the use of technology and measures in barrier construction that are hazardous for animals. It is important to increase the permeability of such fences by leaving openings to allow small animals to pass through the barrier.

These issues can only be reasonably addressed if the planning of new security measures naturally includes environmental and human impact assessments and consideration of a variety of alternatives. In the case of the Polish fence, this is precisely the step that was bypassed under the pretext of extreme urgency. A new law passed since then to enforce the creation of border barriers explicitly excludes such projects from European Union procedures for environmentally responsible planning and management.

At UWEC Work Group, we seek to initiate a discussion among stakeholders in order to avoid or address the negative consequences of planned and existing border barriers and fortifications. In subsequent articles, we will review sustainable technologies for creating animal-friendly barriers and border zones, as well as consider important examples in global practice. Although barriers stopping human border crossings are often detrimental to wildlife, some options can have positive conservation effects. Future articles will analyze new designs for border barriers and fortifications stemming from the current war and its geopolitical fallout.

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Main image credit: ednh.news

Comments on “Can the Iron Curtain Be Green? Europe’s nature is being divided by fences and fortifications”