by Oleksiy Vasyliuk

Translated by Nick Müller

Military hostilities have a significant destructive effect on nature. They not only cause the death of living organisms, but also lead to the destruction of natural ecosystems. As a result, ecosystems lose their ability to support biological species, including humans.

Loss of ecosystem services

All our needs for everyday living depend on the state of the environment: air quality, temperature, precipitation, and food, all of which are directly related to natural ecosystems. For example, 60% of everything that humanity consumes originates from plants pollinated by wild insects. Virtually all plant foods consumed by humankind are grown on soils, while animal-based foods (except seafood) come from animals that rely on fodder also grown on soils: a complex and important ecosystem. It is also not hard to imagine what would happen if plants did not have time to restore the oxygen supply in our planet’s atmosphere. All of these factors point to the fact that the quality of our life and the suitability of lands for our existence depend on the preservation of ecosystem functions.

All ecosystem services can be divided into several groups: supply services (or natural resources), regulatory services that support the natural living conditions for biological species, and cultural and social services, including the cultural (spiritual, aesthetic, etc.) significance of nature for people.

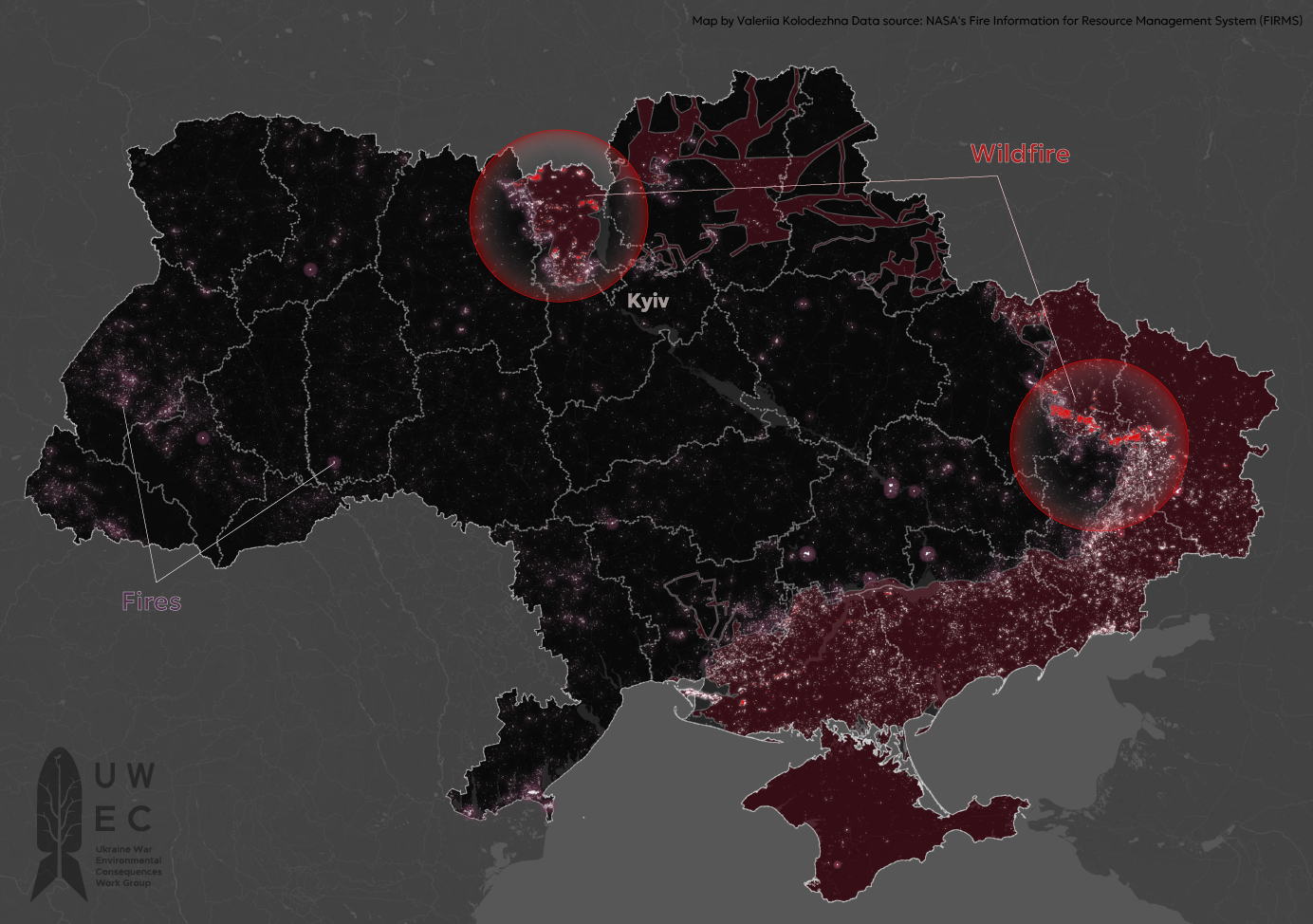

Fires, pollution of rivers and soils, explosions and the destruction they cause, and acid rain all damage ecosystems. The total volume of land burnt in Ukraine as a result of the war already exceeds 100,000 hectares. A significant part of that area is forests, some of which are located in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Waste from destroyed sewage treatment plants and industrial enterprises ended up in rivers and soils, as did all the toxic contents of each of the shells, rockets and mines used during combat.

Before the start of the war, climatic conditions were largely mitigated by previously artificially grown forests and forest belts, which together form the microclimate. The invasion’s disruption of ecosystem services especially affected inhabitants of Ukraine’s steppe zone, a region particularly impacted by recent hostilities. The destruction of forest belts leads to large-scale wind erosion and the devastation of entire regions. Losses of even artificially created but healthy forests in the south and east of Ukraine will result in arid, windy conditions, as well as a significant increase in summer temperatures and a drop in winter temperatures. In the current climate, it is highly likely that it will not be possible to restore these lost forests to their previous condition. Loss of ecosystem service regulation can be felt in the form of declining living standards, increased costs for comfort and health care, and increased food costs. Communities are often left with destroyed and damaged infrastructure and housing.

Another challenge for ecosystem services is the issue of the soil erosion caused by hundreds of thousands of explosions, construction of military defenses, and the passage of heavy military machinery.

Ecosystems are also losing their cultural and social functions. Human visitation of forests and parks contributes to the prevention and treatment of mental health issues, an effect that was most recently on view during the acute stage of the Covid-19 pandemic. Opportunities for enjoyment, spiritual enrichment, inspiration for creativity, obtaining scientific knowledge, and identity formation for social and ethnic groups are also important but unquantifiable ecosystem services.

Who depends the most on ecosystem services?

The impacts of ecosystem services are either concentrated within the ecosystem (for example, peace and quietude) or extend a certain distance away (wind carries cool air formed in the forest to the nearest settlement in summer). In addition, some services are provided by many ecosystems around the world, while others (primarily aesthetic, social, and curative) are unique. It may only be possible to experience their significance (for example, to see natural views) from within. We all use many ecosystem services without noticing: we breathe clean air, admire the horizon, or find peace listening to birdsong after a busy day. When we want to lie on a seaside beach or go mushroom-picking on a damp autumn morning, we go places where nature provides these specific services.

We can identify core groups of ecosystem service consumers: permanent local residents, informed temporary visitors, and consumers of global regulatory services (climate formation, atmospheric precipitation, air chemistry, etc.). Ultimately, the latter group includes all of Earth’s inhabitants.

Long-term area residents are part of the positive impact of each ecosystem service. They are consumers of these services, regardless of whether the consumption is conscious or unconscious. For locals, ecosystem services are an integral part of their quality of life.

When a natural area ceases to provide services for regulating socio-cultural life, local residents tend to suffer the most of all. For example, during combat, ecosystems are partially destroyed and some land becomes inaccessible due to mine deployment. An ecosystem’s destruction (for example, by forest fire) ends provision of most such services. Minefields offer consequences of a different nature: elimination of the direct use of sociocultural services, without stopping ecosystem processes.

Regardless of mines, trees continue to generate oxygen, bumblebees pollinate plants, and moist cool air forms under forest canopies. Residents living adjacent to mined areas also do not experience deteriorating natural conditions, although, if they profit from ecotourism, their income will inevitably decline. When people are forced to relocate, they not only lose a whole range of familiar ecosystem services, but also income from the influx of tourists. So, those involved in local recreation businesses in southern Ukraine are among the hardest hit by Russia’s invasion.

Overall, the importance of sociocultural services should encourage local residents to revitalize and protect nature in order to maintain reliable income in the community. Restoration of recreational opportunities in the war-torn south and east of Ukraine appears to be a more realistic short-term objective than complete revitalization of housing and industrial infrastructure.

Overcoming consequences naturally

Of course the war’s consequences not only affect nature, but nature can also influence the war’s consequences, reducing its negative impact on humans.

Everyone knows about the Chornobil nuclear power plant and its exclusion zone, an area abandoned by people fleeing radiation pollution after the 1986 accident. This incident is a globally-recognized example of nature’s ability to heal in areas where all human activity ceases. Today, its exclusion zone contains the wildest forest in Central Europe; a biosphere reserve has been created on its territory, and many scientists seek entry in order to study wildlife.

Aside from the obvious benefits for wild plants and animals that have regained enormous habitats, reforestation in the exclusion zone is also very beneficial for people. Despite radiation contamination of the territory, local forests provide people with most of the ecosystem services inherent in other forests. They support a mild and humid microclimate in the Polesye region, extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and form clean, oxygenated air that is transported south to Kyiv. It is the exclusion zone’s natural ecosystems that prevent the spread of radionuclides. In addition, this territory is a sort of reservoir, since the regulation and purification of water flowing through its wetlands provide Kyiv with clean water over a long timespan. And, of course, these forests are home to millions of living organisms. While the previously polluted territory may not currently be suitable for human life, it does make life safer and more comfortable for all living organisms.

Eliminating the war’s consequences is a much more difficult task. Explosions of ammunition, passage of heavy equipment, construction of defense lines, fires in forests, and minefields all destroy nature and limit access. War brings the most devastating losses to forests, secondarily so to steppes and meadows, and only then to other biotopes. That said, wetlands avoid most suffering, as they are usually bypassed by military activities. When risked, wetlands are barriers to enemy vehicles, sometimes absorbing them forever. All important wetland functions that play a role in climate formation, regulating water content in rivers, and the preservation of organic matter accumulated in peat for thousands of years remain intact. The same is true for the services of all flooded ecosystems.

Minefields can block access to favorite places, with devastating morale impacts: no more silent walks in search of mushrooms, journeys along well-trodden routes on weekends, or camping overnights with friends. Scientists (even those who study the effects of war) will no longer be able to access sites for nature studies. Teachers cannot conduct trips for students, and university professors cannot organize hands-on training for students. All the beneficial properties of nature that require human presence in ecosystems are completely eliminated where landmines are present.

Ecosystems also help to overcome the war’s consequences, and such natural processes cannot be replaced with technological ones.

Plants, soil organisms, bacteria, and even some animal species carry out biological remediation, such as extracting hazardous substances from soils and water bodies accumulated during munitions explosions when manmade objects burn. Reservoirs, wetlands, and floodplains filter polluted waters and accumulate pollutants. Waterways help dilute those pollutants and transport them downstream to sea. En route, some substances are absorbed and processed by aquatic organisms into less toxic compounds. Forest ecosystems filter out atmospheric pollution and improve the quality of air polluted during combat. Grassland biotopes protect damaged soils from wind and water erosion, restore soil formation, and store atmospheric carbon dioxide. Thus, the restoration of grass cover not only improves the process of soil formation and elimination of pollutants, but also stabilizes climate. Grass-covered soil blocks surface runoff, a process which could carry pollutants into water bodies.

All of this immense work is carried out simultaneously by billions of living organisms, and they do this work simply because they are living their lives. The best solution for war-affected areas should be renaturalization – natural restoration of biotopes – in other words, rewilding. Only in this way will it be possible to effectively overcome the mechanical and chemical consequences of the hostilities that made the land unsuitable for further use. This strategy can be applied to both natural and heavily polluted economic areas as well, generally improving the state of Ukraine’s environment, while increasing the surface area of natural landscapes and ensuring clean air, water, and a more comfortable microclimate. In seeking natural restoration strategies, Ukraine will more effectively achieve the nature conservation goals laid out in the framework of international treaties, in particular, the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Main image source: texty.org.ua

Comments on “Military combat impacts on ecosystem services in Ukraine”