Oleksiy Vasyliuk and Eugene Simonov

At COP15, the Ramsar Convention Secretariat presented an unprecedented report on the impact of Russian aggression on Ukrainian wetlands. This report was prepared following the adoption of a bold anti-war resolution by a previous COP in 2022. Most of Ukraine’s wetlands of international importance have been impacted, both directly and indirectly. Long-term, phased restoration plans and monitoring are necessary to restore the affected wetlands. Right before this presentation Russia withdrew from the convention, while Ukraine successfully pushed through a resolution to continue assessing the impact of the war on Ramsar wetlands.

Russia shoots herself in the foot

The echo of Russian aggression in Ukraine could be heard throughout the 15th Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands, which took place in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, from July 23 to 31, 2025. On the second day of the conference, the Russian Federation’s Ambassador to Zimbabwe, Nickolai Krasilnikov announced Russia’s withdrawal from the Convention due to “politicization”. By leaving the Convention, Russia is canceling the international protection of 4% of all wetlands on the Ramsar List and setting an ugly precedent of politically motivated renunciation of international conservation obligations.

On July 25th Russia’s TASS information agency announced that, “The Ramsar Convention names 50 wetland sites in Russia, with many of them enjoying the highest conservation status as part of nature reserves”. These sites are located not only within Russia but also in Ukraine, including 15 sites in areas currently under occupation.

At the same time, leaving the Convention will result in the cancellation of 35 historically Russian international wetlands. From now on, in the context of the Convention, all international attention and the Russian Federation’s commitments will be focused solely on the Ukrainian Ramsar wetlands remaining under occupation given that Russia has no legal authority to withdraw those wetlands from the Ramsar List. This is hardly a “diplomatic victory.”

Read: Russia exits Ramsar Convention on Wetlands

Resolution XIV.20 and its implementation

The effective trigger for Russia’s exit was the Convention Secretariat’s implementation of Resolution XIV.20 “The Ramsar Convention’s response to environmental emergency in Ukraine relating to the damage of its Wetlands of international importance (Ramsar Sites) stemming from the Russian Federation’s aggression”, adopted in November 2022 at the previous conference of parties.

In addition to condemning the aggression and its impacts on wetlands, the COP-14 called for practical steps in assessing damage and developing mitigation plans. The Ramsar Convention List includes wetland sites where the member states pledged to “preserve their ecological character”, therefore the assessment had to determine which wetlands are potentially experiencing a “change of ecological character” because of the war.

Although unprecedented and criticized by many of the Convention’s signatories, this document has already gained great interest among academics studying international law. Meng Wang, a researcher from the Maastricht University, in an article dedicated to this Resolution argues that “Compared with the Montreux Record (a register within the Ramsar Convention that lists wetlands of international importance where human activities threaten to change their ecological character), the first strength of the Resolution lies in its ability to prompt the timely implementation of focused actions within the legal framework of the Ramsar Convention…as an immediate reaction to the ongoing threats posed by armed conflict.”

Wang highlights that the “Resolution has brought this issue to the forefront of international discussions and prompted media coverage, public debates, and advocacy efforts, thereby creating a platform for sharing information about the environmental impact of the armed conflict…. In addition to raising awareness concerning the environmental emergency in Ukrainian Ramsar Sites, this cooperation has also facilitated the acquisition of expertise and technical support from other institutions.”

Following the events of 2022, the Ramsar Secretariat’s activities under Resolution XIV.20 primarily focused on assessing the impact of the war on Ramsar wetlands. The Secretariat participated in the Inter-Agency Coordination Group on Environmental Assessments for Ukraine, which in 2025 became part of the UGRP (Platform for Action on the Green Recovery of Ukraine).

On March 10, 2023, Ukraine submitted a notification to the Ramsar Secretariat regarding changes to the ecological character of 16 occupied Ramsar Sites and potential changes to the ecological character of an additional 15 sites near the frontline. On April 4, 2023, the Ramsar Secretariat met with the Permanent Mission of Ukraine to the UN Office and other intergovernmental organizations in Geneva. The meeting was held to exchange information on the severity and scope of the damage and to explore strategies and measures for mitigating the potential negative impacts on these sites and ensuring their long-term ecological integrity.

To conduct the “Assessment of Environmental Damage to Ukraine’s Ramsar Sites Resulting from the Russian Federation’s Invasion of Ukraine”, the Secretariat hired a team of three international expert consultants and one national expert. From March to September 2024, the implementation phase included a literature review, specific remote sensing analysis, and ten days of field assessments in Ukraine from May 26 to June 5, 2024. Due to security threats, no sites located in occupied areas or in the vicinity of the frontline were visited. During the mission, the consultants visited six wetlands of international importance. During each visit, the consultants observed a range of conflict-related impacts firsthand. To quantify the intensity of the impacts on individual wetlands, the consultancy team collected qualitative data from wetland site managers through a workshop in Kyiv on May 31, 2024, and surveys. The United Kingdom and the United States financed this assessment work.

Several intermediate reports have been discussed at periodic meetings of the Standing Committee of the Convention and the “Assessment Report of environmental damage on Wetlands of International Importance in Ukraine stemming from the Russian Federation’s aggression” was finalized in January 2025 and presented to the COP 15 on July 25, 2025.

After the report was presented, the Ukrainian representative, Olesya Petrovych, expressed appreciation for the work and requested that the contracting parties support extending Resolution XIV.20, which relates to the damage to Ukraine’s wetlands caused by Russia’s aggression. She also noted that Volodimir Vorovka, a Ukrainian scientist who contributed to the listing of ten Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Sites), was kidnapped by occupation forces in 2022 and remains imprisoned in Russia and called for his immediate release. The representative of Indonesia called for a global wetland restoration fund to support Ukraine and other sites impacted by conflicts.

Ramsar Report Findings

The assessment report notes that data on the impact of Russian aggression on wetlands of international importance is generally quite limited. The most available data relates to direct impacts, such as the presence or absence of hostilities or bombing, military training, the number and extent of fires, the likelihood of landmines, changes in the hydrological regime, movement of heavy military vehicles and equipment, construction of trenches and defensive structures, incidents of fuel, chemical, and household sewage or garbage pollution, and use of ecosystem services or bans on their use.

Five types of impacts—fire, flooding, water regime, water quality and military infrastructure—could be investigated using remote sensing from open-source datasets and analyses. For thirteen out of the fifty Ukrainian wetlands of international importance, relevant impacts were confirmed with high confidence using remote sensing data. For instance, the study showed that military infrastructure, such as trenches, roads and training grounds, has been built in the immediate vicinity of some wetlands of international importance.

Due to the nature of wetlands, changes in hydrological regimes caused by events directly or indirectly related to Russian aggression were identified as the primary factor in changes to ecological character.

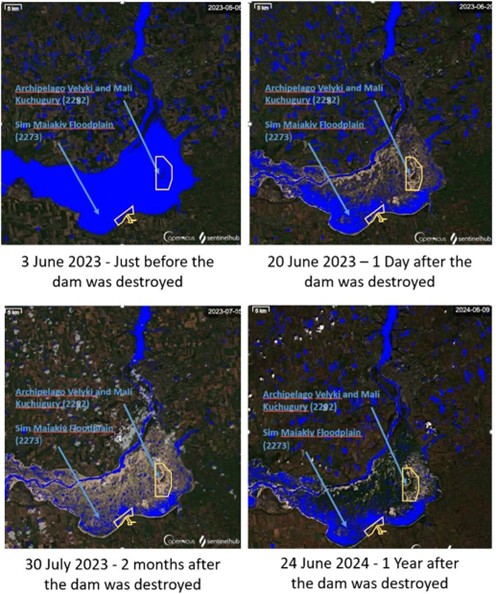

Four sites (Molochnyi Liman, Velyki and Mali Kuchugury Archipelago, Sim Maiakiv Floodplain and the Dnipro River Delta) were assessed as having experienced a “major change in ecological character” as the data indicated a significant impact on all ecosystem components, particularly the hydrological regime. Three of those sites experienced dramatic changes in ecosystem conditions, such as land drying up and new inundated areas following the breach of the Kakhovka Dam. These changes were clearly visible in satellite photos and severely disrupted ecological functions and services.

Twenty-seven sites where a fairly strong impact on ecological components, processes, or services was noted are associated with military or defensive actions or a change in the hydrological regime resulting from hostilities, and are classified as sites where a “moderate change in ecological character” occurred.

The impact on sites outside the zone of occupation or military hostilities largely relates to indirect impacts. These include reduced management capacity and funding, as well as reduced access to some ecosystem services. In such cases, it was determined that a “minor change of the ecological character” occurred. The analysis showed that 17 sites were affected in this way. Only two sites, with a total area of 300 hectares, were unaffected.

Thus, of Ukraine’s 50 wetlands of international importance that cover a total area of 930,000 hectares, 48 have been directly or indirectly impacted by the war. The types of impacts from the war, as well as the resulting degree of change in the ecological character of wetlands of international importance, are summarized in the table below.

Ecological character change in Ukraine’s 50 wetlands of international importance. (Source: Ramsar report)

| Nature ofimpact | Change in ecological character | Characterization of impact | Example of change in ecological character | Number of Sites |

| Direct | Major | Significant impacts on all components of the ecological character of the site | Fundamental change in hydrology resulting in the elimination of the wetland ecosystem, and its associated ecosystem services | 4 |

| Direct | Moderate | Some significant impacts on some components of ecological character | Occasional shelling, troop and military vehicle movements, military construction, etc. | 27 |

| Indirect | Minor | Reduction in site management staff capacity, funding, equipment or reduced access to some ecosystem services | Reduction in access to ecological services, such as local tourism and recreation, reeds mowing or fishing. | 17 |

| None | None | No change in ecological character | — | 2 |

Mitigation and restoration planning

The assessment report recommends creating a wetland restoration plan for each affected Ramsar wetland and suggests the order and specifics of immediate, short-, medium-, and long-term remediation activities.

Immediate actions that could be implemented while the war is ongoing include enhancing the use of remote sensing to monitor damage and changes in wetland ecosystems, supporting and encouraging remaining management staff to monitor and document impacts, training and resourcing local authority and community rapid-response/containment teams to address immediate pollution risks with containment barriers, and providing equipment and training for water and soil quality testing and wildlife assessments.

While developing wetland restoration plans, the optimal sequencing of restoration activities must be determined in consultation with local experts to minimize unnecessary damage to biodiversity. Priority should be given to removing explosives, waste, and debris, as well as restoring the hydrology of the wetlands, especially where ditches and channels have been constructed for military purposes.

Many impacted wetlands, particularly large ones, will require significant effort, funding, and resources for remediation. The report suggests that these activities may require moving heavy machinery and people into the wetlands to perform various tasks, such as excavating and transporting contaminated soil and sediment, demining, and removing unexploded ordnance (UXO) and military waste. These activities have the potential to further damage natural ecosystems, so they should be carried out using a phased approach. Ramsar experts suggest dividing wetland sites into smaller lots and demining and remediating each lot separately over several years. While remediation is underway in designated zones at one site, similar activities should be prohibited in nearby wetlands to allow for the establishment of alternative colonies, foraging areas, and wintering grounds. Remediation activities should be carried out during seasons of low biological activity, preferably winter, to minimize stress at a given site.

UWEC experts reviewing these recommendations have expressed reasonable doubt that the removal of contaminated soil and sediments is a priority approach beyond areas where their presence poses an immediate threat to human health, and furthermore that this cannot be accomplished through in situ remediation measures (e.g., phytoremediation). For wetlands, removal of substrate (including contaminated sediments) can lead to even more catastrophic consequences—destruction of the hydrological regime and loss of silt accumulated over many decades, which serves as habitat for many invertebrates, which in turn are the food base of birds—focus of protection under the Ramsar Convention.

The Ramsar report also brings up the example of “delayed action” at heavily mined areas in northern France that were designated as nature reserves and classified as no-go zones (“zones rouges”).

Read more: Future of munitions-damaged Ukrainian lands

Wetland restoration plans may include measures such as decontaminating polluted sites, establishing new buffer zones, reintroducing endangered species and improving vegetation management. However, these actions must consider the severe risks posed by remaining pollution and explosives.

The report acknowledges that the objectives and activities of restoration plans differ significantly according to site-specific conditions and wetland ecosystem types, including coastal, deltaic, floodplain, and inland wetlands.

It includes a separate list of recommendations for wetlands on the border with Belarus. There, the hydrological regime of peatlands and wildlife migration has been impacted by the construction of defensive structures on both sides (e.g., Shatsk Lakes, Prypiat River Floodplain, Perebrody Peatlands, and Polesye Mires). The authors of the report note that “the possibility of restoring these wetlands, which should be undertaken on both sides of the border, will depend on the political situation and the normalization of nature conservation co-operation between the two states, which was quite active before Russian aggression began.”

Read more: Protected areas and border zones in Ukraine: How to harmonize them?

The Ramsar report discusses the fate of Velyki and Mali Kuchugury Archipelago, former islands in Kakhovka Reservoir and now the driest part of its exposed bottom. While the Ukrainian government pledged to rebuild the reservoir, the report notes that this may not be the best option for wetland restoration. Despite the dramatic change in the area’s ecology, the report acknowledges that the Kakhovka Reservoir’s base is a historical floodplain for the Dnipro River. Several Ukrainian scientists argue that it may have even greater ecological value as a single, large wetland.

The authors of the Ramsar report strongly emphasize that the “European Water Framework Directive and the recent EU Nature Restoration Law encourages member states to restore nature, including watercourses, and remove barriers such as dams wherever possible. Accordingly, the restoration of the Dnipro River floodplain (historically known as the “Great Meadow”) could become one of the largest wetland restoration projects not only in Ukraine, but also in Europe”.

Fate of Wetland Communities

The Ramsar report emphasizes that remediation measures should aim to restore ecosystem services, allowing communities to recover socially, economically, and in terms of health and well-being. Essential wetland ecosystem services, such as food provision and water purification, must be restored for local populations. To create more resilient communities around wetlands and rebuild livelihoods, the report provides several preliminary recommendations.

“Assessment Report recommendations for resilient communities”

I. Ecotourism development: Investment in ecotourism infrastructure, such as trails, birdwatching platforms, and visitor centers, can generate additional income for local communities. The return of domestic tourism is crucial for ensuring the well-being of communities, but new tourism regulations may be necessary for security reasons and to ensure the ecological recovery of wetland sites.

II. Sustainable Fishing and Agriculture: Training in sustainable techniques and access to alternative livelihoods, such as aquaculture, should be provided.

III. Crafts and Local Production: Supporting traditional crafts like reed weaving and other wetland-based industries could provide income while preserving local cultural practices.

IV. Capacity Building and Education: Enhance education in sustainable land use practices and wetland conservation to promote long-term stewardship opportunities.

V. Access to Financing: Provide microfinance programs or grants for green businesses and sustainable development projects.

VI. Job Creation in Conservation Work: Employ local people in the conservation and restoration of impacted wetlands. Include roles in habitat management, monitoring, and tourist guiding.

VII. Community Participation in Decision-Making: Engaging communities in post-war reconstruction and wetland management.

VIII. Food and Water Security: Wetlands often provide essential ecosystem services, such as water purification and food resources. Restoring these functions quickly can help prevent food and water insecurity during the recovery phase.

IX. Health and Well-Being Support: Mental Health and Trauma Care: Post-war recovery for affected communities should consider the mental health impact of the conflict. Programs that promote healing and well-being are essential for rebuilding resilient communities.

Thus, the report emphasizes the central idea of the Ramsar Convention: the long-term resilience of Ramsar wetlands is based on the local population’s practice of “wise use of wetlands”.

Read more: After the deluge: Life on the banks of the Kakhovka Reservoir now the water is gone

Ukraine’s Success at COP 15

On July 28, Ukraine requested that the assessment work continue since ongoing Russian aggression continues to damage wetlands. The country presented a relevant draft resolution (COP 15 Doc. 23.26), which calls for additional wetland monitoring activities.

On behalf of 40 co-sponsors, Estonia emphasized the need to address environmental degradation during armed conflict. They stressed that, since the adoption of Resolution XIV.20, the consequences for people, biodiversity and ecosystems in Ukraine—including wetlands of international importance—have worsened.

China, Cuba, Indonesia, Iran and Venezuela stated that the COP should focus on scientific and technical issues because there are more appropriate forums for discussing political issues. China added that discussing highly politicized issues may distract from the core task at hand and requested that the COP retain its focus on shared conservation goals.

On the last day of COP 15, the fate of COP 15 Doc. 23.26 was decided by a secret vote. The resolution was adopted after 46 countries voted in favor of it, 11 voted against it, and the rest abstained from voting. (There are 171 Contracting Parties of the Convention, not including the Russian Federation which has denounced it and Saudi Arabia which just announced its accession.)

Conclusion

The first effort by the Ramsar Convention to assess the consequences of Russian aggression on Ukrainian wetlands revealed that 96% of these wetlands have been affected by the war, with over half experiencing direct detrimental impacts. Affected wetlands span nearly 1 million hectares. An additional 10 million hectares of wetlands lost Ramsar protection in Russia after the government demonstrated its discontent with the Convention’s assessment activities in Ukraine in the most extravagant and barbarous way.

The Ramsar report provides detailed recommendations for wetland restoration planning and calls for the restoration of community livelihoods living around the affected wetlands. The assessment emphasizes the necessity of a long-term, comprehensive environmental monitoring program to accurately determine the extent of the damage inflicted on Ukraine’s Wetlands of International Importance by the Russian invasion.

Discussions on the new Ukrainian resolution, the scope of which is strictly limited to the continuation of assessment work, as well as other similar proposals made by other parties during COP-15, have shown that a growing number of Convention parties are uneasy with bringing such controversial matters to the “technical forum on nature conservation.” Nevertheless, the resolution was adopted by a majority vote and will allow for the continued improvement of monitoring and assessing war damage to wetlands under the auspices of the Ramsar Convention.

Main image: Olesya Petrovych, representative of Ukraine at Ramsar COP 15. Photo: Anastasia Rodopoulou/ENB-IISD