Eugene Simonov

The economic sanctions imposed against Russia for its war in Ukraine are likely to have broad consequences, including social and economic repercussions. Whether these sanctions have some kind of useful environmental “side-effect” depends not only upon their scale, but also on the detailed preparation of sanctions legislation and, most importantly, on the political will and administrative abilities of the government bureaucracies implementing them. Here we look at the controversy surrounding the Australian company Tigers Realm Coal Ltd. (TIG), which owns “Beringpromugol” and several other coal companies in Russia’s Arctic territory of Chukotka in the north Pacific and which recently announced the sale of its Russian assets.

Environmentalists place their hopes in sanctions

When the West imposed sanctions and other measures intended to wean Europe off its dependency on Russian carbon and oil, environmentalists were mildly euphoric. Many thought that the harmful supplies of Russian carbon fuel would be replaced by green energy. This is partly what happened, though progress turned out to be substantially more modest than anticipated, and the environmental concerns still need to be addressed. The European Union’s foreign economic efforts contributed more to renewed development of gas fields than to the growth of renewable energy sources in developing countries. At the same time, some supposedly green EU investments designed to weaken former Soviet states’ ties to Russia, such as support for giant hydroelectric power plants, have proven to be clearly harmful.

Read more: “А la guerre comme à la guerre”: Military geopolitics see return of controversial megaprojects

As for the other side of the sanctions, progressives also had rosy expectations that a catastrophic decline in Russian exports, and therefore production, of coal, oil, and gas, would reduce Russia’s carbon footprint. As we now know, this has so far happened only with gas – essentially the least environmentally harmful of all Russia’s fuel exports. Russian oil is still king in markets in the developing world, and even the much-maligned coal is holding its ground. India has found itself a new supplier, while China has substantially increased its coal imports, creating greater opportunities for Russian exports.

Coal miners vs. Indigenous communities

On September 20, 2011, Stanislav Taranenko, the head of Altar, an indigenous family community association in Chukotka, woke up in his trailer on the edge of the breathtaking Amaam lagoon near Ushakov Bay on the peninsula’s southern coast. He had been awakened by the noise of heavy machinery. Running out of the house, Taranenko saw a ship, which had just unloaded a tractor onto his section of the shoreline. The vehicle was rumbling into the tundra across the community’s lands, cutting up the fragile turf of the reindeer pastures with its caterpillar tracks. Taranenko drove his all-terrain vehicle out to the place where the ship was moored and did not allow it to unload the rest of its cargo. Members of the community blocked unloading of the vessel for four days, an action for which the Northern Pacific Coal Company (“STUK”) later took them to court, seeking to recover half a million rubles (approximately $17,000 at the time).

For the Altar community, this marked the beginning of many years of confrontation with Tigers Realm Coal, a coal company sponsored by the administration of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug (ChAO), which had acquired a license to mine the giant Amaam coal deposit, located amid the indigenous Chukchi people’s ancestral lands. The administration of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug gave the company a slap on the wrist, ordered it to ensure that equipment was transported by air instead of by land, and… promptly announced to the Altar community that it had no legal rights to 7,000 hectares of ancestral lands, since “the documents were drawn up incorrectly.”

Over the next few years, the community, with the support of Indigenous peoples’ associations, human rights foundations, environmentalists and independent media, managed to defend its case and win a series of lawsuits against the company and the district administration. However, Altar was ultimately unable to survive pressure from the hostile authorities and in 2021 the group was forced to dissolve itself.

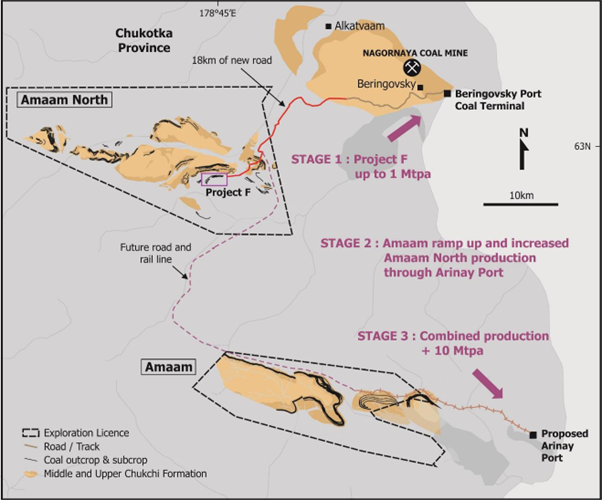

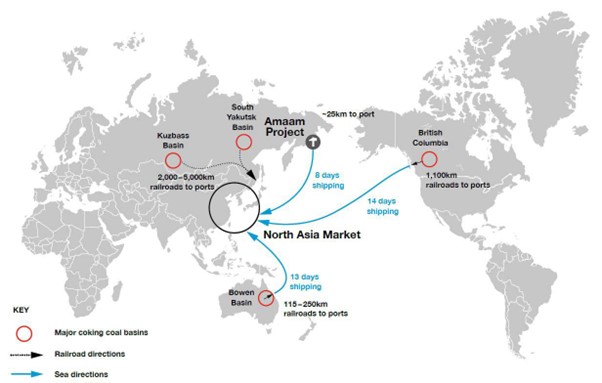

For Tigers Realm Coal (TIG), this marked the beginning of an extremely successful business operation in Chukotka. In the 2010s, it had become obvious that the bottleneck created by Siberia’s limited rail network – the Trans-Siberian and BAM (Baikal-Amur Mainline) – made it difficult to export coal from the huge coal mines of the Kuzbass region, located in the center of Siberia. The Kuzbass could not compete with coal-mining enterprises based on the very edge of the Pacific, which face no obstacles in exporting their goods to Asian markets, since the coal is loaded directly onto ships. Realizing these advantages, TIG stepped up its operations, purchasing STUK and exploration licenses for two large coalfields, Amaam and Severny Amaam (also known as Alkatvaam and Fandyushkino Polye), capable of providing over 5 million metric tons of coking coal and coal for export annually. To facilitate these exports they commissioned the construction of a deepwater port in the Arinai lagoon and awaited the arrival of the big investors.

Sanctions no obstacle to growth: the ‘Russification’ of Tigers Realm Coal

But at this point Russia annexed Crimea and came under the first Western sanctions. Foreign investors – even the Chinese – suddenly lost interest in the project. Undeterred, TIG curbed its appetite and fell back on its chief supporter – the Russian state. Moscow bestowed the preferential status of “Advanced Development Zone” upon the company’s coal mines and even bought a stake in the Australian company through its Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF).

“We are a de facto Russian company. We need a listing in Australia because there is traditionally a lot of investor interest in the coal industry there,” the Australian company’s then-chief operating officer Peter Balka unabashedly declared in an interview with a Russian media outlet in 2016. TIG managers gushed praise to the administration of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, which was supporting them in every possible way, including by “working with the local Indigenous population.”

The change in the company’s plans necessitated by sanctions on Crimea did have one good consequence for nature – the construction of a seaport was postponed indefinitely, saving the remote lagoons of Amaam and Arinai from environmental disaster. The introduction of sanctions rendered the development of the Amaam deposit no more than a vague prospect, and TIG focused on the more accessible Fandyushkino Polye deposit and the export of coal through the existing port in the village of Beringovsky.

Unfortunately, the company still inflicted great harm: local communities regularly complained that there were no fish in the river in the watershed where the deposit was being developed, the coal mine itself and the roads leading to it deprived people of access to the nearest berry fields and hunting grounds, the expansion of mining activity threatens reindeer pastures, etc.

But the district authorities always took the company’s side whenever they could, stepping in to help defuse conflicts. Almost every year, villagers complain about coal dust resulting from violations during loading, but it continues to circulate.

In this remote corner of Russia, TIG also became a monopoly, when the local Nagornaya coal mine, which had operated for 30 years before TIG’s arrival, closed down. It is noteworthy that, prior to shutting down, Nagornaya reduced its skilled labor shortage by bringing in Ukrainian shift workers from Donetsk. In a strange coincidence, it was exactly in the same year that, when TIG needed the use of the old Beringovsky port in its entirety, that the ChAO administration terminated Nagornaya’s 50-year contract and stopped purchasing coal from the mine, citing its “unprofitability.” Since then, TIG has been supplying coal for local settlements, sponsoring a kindergarten festival and helping Indigenous communities preserve their culture. Essentially, the local administration has no one to turn to for support except TIG.

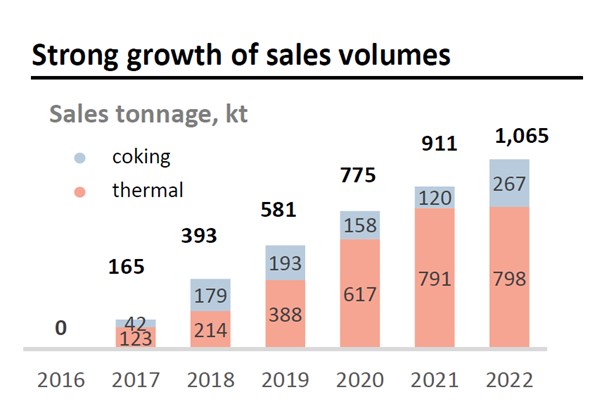

TIG takes on the courts – and loses

By 2022, TIG was growing at a rapid pace, with exports exceeding 1 million tons per year. The company was now making profits, had renovated the port, and was investing in factories to improve the quality of its coal on site. But then Australia, following the example of other Western countries, announced the introduction of its own “autonomous sanctions,” which included a ban on the transportation of Russian coal – though the government did almost nothing to identify or pursue violators. In 2023 TIG itself asked the Australian government whether the company was violating the sanctions regime, and was informed that it probably was.

Australian civil society has now realized that in violating sanctions for a year already, the company is helping Russia to grow the economic potential necessary to fund its war and has gone on the attack. The Australian Centre for International Justice, Transparency International Australia and the Ukrainian NGO Razom We Stand have made an open appeal to officials about the necessity of upholding sanctions and not turning a blind eye to violations.

TIG then decided to strike first and filed a lawsuit against the Australian government, challenging the legality of the sanctions. With this tactic it was killing two birds with one stone – not only did the legal action delay for a year the decision to punish the company for violating sanctions, but it also silenced public opposition, since attempting to influence a court’s decision-making process is strictly regulated by law, and accordingly limits any possible activism against the company. At the same time, representatives of TIG played the company’s opponents for fools, declaring that in the sanctions legislation the concept of “coal transportation” did not apply to its transportation across Russian territory.

In her comprehensive reports on this saga for Australia’s Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), correspondent Lera Shvets described how this discussion unfolded in the courtroom: “The court heard that DFAT’s interpretation of ‘transport’ was too broad, and that ‘an Australian citizen using coal produced in Russia to heat his apartment in Moscow’ would also then be captured by the same regulations. Representing the Commonwealth, Perry Herzfeld, SC, responded by saying that instead of this “terrifying” example, the court should consider another one: an Australian company mining Russian coal and selling it abroad, and paying taxes to the Russian government from that.

Only in April 2024 did the court finally rule on what constitutes “coal transportation”, opening the way for TIG to be recognized as in violation of sanctions. In response, the well-prepared TIG announced that it would sell its Russian assets to Russian businessman Mark Buzuk, a longstanding associate of all Russia’s oligarchs, for $45 million (a sum commensurate with the company’s profit in 2023). The company is allegedly worried that if it falls under sanctions its assets will be forcibly confiscated by the Russian government. In either scenario, however, the demise of TIG will be welcomed by certain oligarchs with close Kremlin ties, who will acquire a ready-made coal mining and regional export chain essentially for peanuts. Meanwhile, the Russian budget will continue to receive taxes from the company.

According to TIG, the proceeds from the sale of its assets will be distributed among shareholders “in strict accordance with sanctions legislation.” Activists are now asking how such a deal can be approved at all if the RDIF (itself under sanctions) is one of the legal shareholders. A decision on the sale is due to be made on 28 May by the company’s board of shareholders.

Will sanctions have any environmental benefits?

At the same time, neither the court nor the Australian government ever considered the harm potentially caused to the environment and local residents by TIG’s main activities. In fact, nature and Chukotka’s Indigenous population probably gain nothing from this method for “application of sanctions.” Beringpromugol’s main coal asset will be just as harmful in the hands of Buzuk (or someone he represents) as it was under TIG. The hope is that Buzuk (and the Russian state) do not have the funds to build a new port in the Amaam and Arinai lagoons. But TIG had no funds for that either. The company’s transparency, which was previously extremely unsatisfactory, will now drop to zero; we will no longer see its reports on the Australian stock exchange.

As for adding coal to the fire of climate change, the company’s mining operation will have lost none of its advantages, and exports to Asia from the shores of Chukotka have a clear logistical advantage over coal from the Kuzbass.

In her article about the results of the case, Lera Shvets cites Christopher Michaelsen, an associate professor in the law faculty at University of New South Wales, who proposes extending Australian sanctions to Chinese companies importing coal, oil, and gas from Russia. Against the backdrop of the gradual warming of Sino-Australian relations, of which Australian coal exporters are the main beneficiary, this is a highly unlikely scenario. And if such a decision is taken, then it will appear that the Australian government is using the war in Ukraine to maintain its position as a leading exporter in global coal markets, where Australia is one of the top three exporters of coal, particularly to Asian countries. Ironically, however, it is quite likely that the high-quality Australian coal (which is not subject to sanctions) that is once again flooding Chinese markets will edge out Russian coal, the import of which is objectively a much greater headache for China. However, it is the Kuzbass rather than Beringpromugol that is likely to be the first casualty in this competitive struggle.

Whatever the outcome of the Tigers Realm Coal saga, at least two lessons are clear:

- Having introduced a sanctions regime, a state must consistently and proactively apply it, otherwise it will make a complete mockery of the very idea of sanctions (which in any case is very dubious in some places);

- When introducing sanctions in environmentally and socially sensitive areas, governments must think about how to optimize the desired result, not only from the point of view of punishing the aggressor, but also in terms of achieving important environmental, climate, and other foreign policy goals.

Translated by Alastair Gill