Translated by Jennifer Castner

The population of the endangered (IUCN Red List) Caspian seal is declining precipitously. The mysterious November 2022 deaths of 2,500 seals has prompted many hypotheses, including those related to the war in Ukraine. Whatever the cause of the die-off, geopolitical tensions due to the war may decrease chances of the species’ survival in the long term, while its preservation requires immediate international conservation measures.

Biodiversity’s role in the war

Biodiversity has become a powerful informational weapon in the war. From the war’s first days, shelling of Ukrainian cities has been justified by the need to “destroy American military biological laboratories” and “proof of biological weapons development” emerging from temporarily occupied areas. Evidence included, for example, visual aids on the spread of bird flu by ducks.

In the fall, the Russian Federation convened a consultative meeting through the Biological Weapons Convention to showcase photographs of an allegedly captured drone with compartments for transporting and spraying mosquitoes and a US patent on a similar device. Most Convention member nations were not convinced by Russian arguments.

On the other hand, photographs of domesticated and wild animals that allegedly died during military action in occupied zones are actively published in the world press, and volunteers who risk their lives to save these animals become modern heroes.

Military propaganda exploits both a terror of pathogenic organisms and pity for wildlife. Because it is currently not possible to independently fact-check events in the conflict zone, the veracity of many reports cannot be confirmed or denied. A recent tragedy in the Caspian Sea clearly demonstrates this challenge. In early December, approximately 2,500 decaying bodies of Caspian seals washed up on the coastline. The Caspian seal is an endemic species which, despite opposition by the commercial fishing lobby, was recently listed as at-risk in the Russian Federation Red Book.

The sea had just begun to throw half-decomposed seal bodies onto the beaches of Makhachkala (Dagestan), when Russian Duma member and member of the Duma Committee on Security and Anti-Corruption Abdulkhakim Gadzhiev had already claimed that the deaths were likely the result of activities by US biological laboratories sited in the Caspian Sea countries. It is more suspicious that such die-offs of seals have been observed repeatedly in recent years.

Indeed, this is not the first such die-off. The bodies of several hundred to several thousand dead seals are documented on northern Caspian shores at least once every three years (and usually without a clear explanation). It can be confirmed that in most cases, the die-off occurs between October and December, when Caspian seals migrate from the southern Caspian Sea to northeastern waters. There, ice fields form, creating optimal conditions for seal reproduction. The same seasonal mass mortality during migration is also characteristic for the Baikal seal, but die-offs there occur less frequently and fewer animals die.

Poisoning by rocket fuel and large-scale gas emissions: “Can’t be disproven”

Russian journalist Yulia Latynina offered a hypothesis to explain the seal die-off in her Twitter account on 5 December. She suggested that the seals were poisoned by rocket fuel during recent shelling of Ukraine:

Tu-95 aircraft were assembled (at the airfield) in Engels. They take off, fly over the Caspian Sea, and launch their (cruise) missiles at Ukraine. Why over the Caspian? Because missiles, especially the X-55, are ancient junk. And when thes antiques fall from the plane, their engines do not always fire up. “Every second X-55 that is deployed [fails to reach its target],” says (military blogger, former pilot) Roman Svitan. Can you imagine what will happen if they are launched over Saratov? So that’s why they launched over the Caspian, where, by the way, 2,500 dead seals were recently found on the shore. Let me remind you that the fuel of these rockets is deadly poisonous.

For all its exoticism, the rocket version is difficult to refute. The X-55’s rocket fuel is a toxic “decylene” (also known as T-10, chemical formula С10Н16). The fuel’s exact composition has been classified since Soviet times, but Issue 10 of Innovative Science in 2021 published an article entitled “Chemical Accident Prevention by Indication of Decylene-M Rocket Fuel Vapors in the Air,” where it is reported that “decylene-M fuel consists of limited polycyclic hydrocarbons. Polycyclic hydrocarbons have enhanced central nervous system depressant properties.”

In the United States, the toxicological data sheet of the analog JP-10 fuel indicates that the substance is not dangerous for aquatic organisms in water, but swallowing or inhaling its vapors can be deadly poisonous, causing pulmonary edema and asphyxia. So, if light and highly-volatile decylene formed a spot on the water’s surface and began to evaporate, then seals surfacing for a breath of air could potentially be poisoned. In this case, fish and other animals breathing under water would not be affected.

In 2004, journalists put forward an explanation about missile testing causing seal poisoning. They wrote about it during a die-off and beaching of seal corpses near Severodvinsk on the White Sea. However, UWEC has been unable to find other references connecting rockets and seals. Again, mass mortality of seals has been observed in previous years in the Caspian Sea. 2022 saw, however, the first large-scale launch of obsolete missiles over the Caspian.

The fact that many seals died while the potential number of missiles lost in the Caspian Sea during the entire course of the war likely totals just a few dozen undermines the missile fuel argument. (In total, according to Ukraine’s Ministry, the Russian Federation fired 150 Kh-555 missiles between February 24 and November 22.) One rocket contains one to two metric tons of fuel, so even if hundreds of rockets fall into the sea, it is assumed that just 100-200 metric tons of fuel pollution could have occurred, while hydrocarbon spills at sea with known serious negative consequences were hundreds of times larger.

Latynina and Svitan’s version of events acquired a new dimension when media in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan began to discuss seal corpses discovered in a “military-political context”. Those journalists conclude this reason to be the confirmed cause of death, given that Russian planes began to drop faulty missiles not into the Caspian, but over Volgograd Oblast while shelling Ukraine in mid-December.

This does not ultimately validate the “rocket” explanation, but it may indicate that Russian leadership has stopped launches over the Caspian Sea to avoid provoking international friction with neighbors who are unenthusiastic in their perception of the expansion of “military operations” to the Caspian region. Additionally, the Ukrainian Armed Forces reported that, as of 14 January, Russia has resumed use of TU-95 airplanes to fire on Ukraine while overflying the Caspian Sea.

Chair of the Dagestan branch of the Russian Geographical Society Eldar Eldarov proposed that military exercises could cause seal mortality. However, he immediately expressed his reservation that it is more likely the cause of the die-off in 2020 rather than in 2022. Military exercises in 2020 involved warships and aircraft and were accompanied by the launch of cruise missiles.

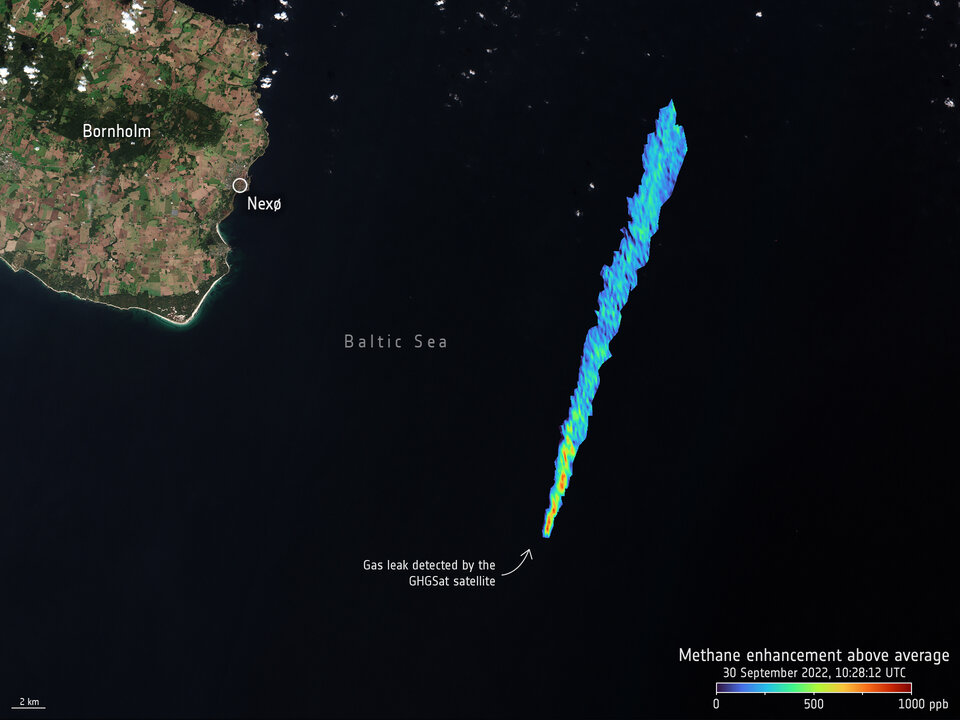

Long before the results of studies of the dead seals were available in Russia, a semi-official version of events arose and took hold: the seals died of asphyxiation – oxygen starvation. The reasoning suggested that seals surfaced and drowned in a cloud of methane released naturally from the seafloor as a result of seismic activity. The regional government in Dagestan and Russia’s head of Rosprirodnadzor (Russia’s environmental watchdog), Svetlana Radionova share this opinion. Radionova also serves on the board of trustees of the Compass Foundation, an organization that had earlier stated that the release of methane from the explosion of the Nord Stream gas pipeline could harm seals in the Baltic Sea. UWEC has not been able to confirm this version of events.

The methane emission theory in the Caspian is convenient in that there is no one to blame and that it is also very difficult to prove or disprove. This same idea was proposed by a number of specialists and geologists to explain the death of seals in Lake Baikal, but was never deemed to be the leading cause.

A large team of scientists commissioned by commercial fisheries institutes prepared a justification of the methane hypothesis for the Caspian Sea in an assessment entitled “On the death of Caspian seals on the Dagestan coast of the Caspian Sea in autumn 2020 and its possible causes” and published in the “Russian Federation Research Institute of Fishery and Oceanography Proceedings.” The result of that assessment is clearly stated:

During the course of research, 12 sites totaling 49.2 km [of coastline] were surveyed. 313 bodies were documented in that area. The total number of dead seals in December 2020 was estimated to be 2515 ± 443 animals. The dead animals mainly consisted of adult females, the majority of which were pregnant. The bodies showed no signs of infectious disease or starvation, and judging by their appearance, the animals’ deaths occurred in the first twenty days of December at some distance from the shore.

Analysis of the collected data makes it possible to exclude infectious diseases, parasites, toxic substances, entanglements with fishing gear, and the impact of an underwater shockwave from among the possible causes of the seals’ death. The most likely cause of death was declared to be acute asphyxia stemming from nearby release of natural gas, which formed a gassed lens of air unsuitable for breathing above the sea surface.

Figure 1. Map showing the locations of dead seals in Dagestan in 2020. Source: Rozhnov et al., 2022.

Scientists have resorted to proof by process of elimination. There is no direct evidence for methane as a cause of death, while three small earthquakes that could possibly trigger methane emissions occurred at the time of the animals’ death. Meanwhile, methane emissions are easily detected using satellite remote-sensing methods. Given that methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, several specialized agencies monitor its natural and anthropogenic emissions, including emissions stemming from the oil and gas industry in the Caspian region. Why the scholars did not attempt to use that monitoring data to support their version is a mystery.

Figure 2. Methane emissions from the Nord Stream gas pipeline rupture in 2022 (first) and methane plume from oil and gas industry infrastructure in the Caspian region in 2020. Source: European Space Agency.

The majority of specialists UWEC surveyed outright refused to consider methane emissions as the seals’ cause of death, calling it extremely unlikely and unprovable.

Methane and rocket fuel poisoning as triggers share a similar deus ex machina aspect, a manifestation of supernatural forces that harken back to endings in ancient tragedies.

Other down-to-earth explanations on causes of seal death

Aside from military and exotic causes of death, there are other hypotheses for the die-off of pinnipeds in the Caspian Sea.

- Infectious disease

Greenpeace program manager Vladimir Chuprov told Kedr-Media that, when studying past seal die-offs, data collected by that NGO indicate that animal death is likely associated with reduced immunity and disease. However, they were unable to determine the exact cause.

According to the Biodiversity Conservation Center data, in May and June 2000 approximately 30,000 dead seals were found on the coasts of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan. The die-off occurred mainly in the northern Caspian Sea in springtime. At the time, most scientists found canine distemper as the main cause of death in seals.

Thus, the largest one-time seal die-off in history is believed to have been epizootic in nature, and other environmental factors may have contributed.

- “Peaceful” pollutants toxicity

Oilfields in the Caspian not only emit methane, but also numerous other pollutants hazardous to ecosystem health. Thus, the decline in the number of seals from one million to just 70,000 over the past century is correlated with the oil industry’s development. This is especially evident in Kazakhstan, where most of the seals now reproduce. Thousands of settlements also dump untreated wastewater directly into the Caspian Sea.

Toxicological research on seals along the Iranian coastline of the Caspian Sea have shown extreme levels of mercury and DDT, toxicants that can adversely affect the health and reproduction of animals.

Pollutants can also result in chronic weakening of populations, but it is difficult to assign them blame for a single die-off event.

- Death by fishing: legal or illegal fishing

The last two centuries have seen excessive seal hunting, quite legally until 2006. In 1935, a record number of 228,000 Caspian seals were harvested. The chronically poor population of the Caspian region, for example, in Dagestan, has long engaged in illegal poaching of these animals on a very large scale. However, a single die-off is unrelated to seal poaching.

In an interview with UWEC, Vladimir Burkanov, member of the Board of the Council for Marine Mammals executive team and International Union for Conservation of Nature Pinnipeds Expert Group member, said that seal bycatch during poaching and legal fishing may turn out to be the leading hypothesis for the cause of the die-off. After a ten-year hiatus, trawler fishing for anchovies resumed in the Caspian Sea in 2019, timing that coincides with increased seal deaths during the fishing season (October-December). Seals often suffocate and drown in trawls and other fishing gear. Burkanov believes that this is the most likely cause of the 2020 seal die-off.

However, the academicians who developed the methane hypothesis deny this version, referring to the fact that three dozen of the corpses they autopsied in 2020 did not have anchovies in their stomachs, and the fish species they found typically prefer shallower habitats. Burkanov noted the incomplete overlap in areas where the seals washed up and where anchovy fishing took place. Moreover, data collected by the authors of the methane hypothesis indicates no evidence of net entanglement was found on the corpses they examined (Rozhnov et al. 2022).

However, other witnesses, including Zaur Gazipov, general director of the Caspian Environmental Center, told reporters that in the 2020 event some of the dead animals exhibited traces of net entanglements on their bodies. On the other hand, animals suffocated in small-mesh anchovy trawl nets should not show the scarring and wounds that are characteristically found on corpses removed from the large-mesh sturgeon nets used by poachers.

In his interview, Burkanov summarized his “ranking” of possible causes as follows:

Of all the possibilities, I would categorize two of them as most likely – death in fishing gear (a cause evaluated very superficially and unconvincingly in the article cited above) and death caused by biotoxins appearing during harmful microscopic algae blooms. I am quite surprised that the latter cause was never even mentioned, given that it could have been a cause of seal death in the past. In recent years, poisoning cases and the death of a number of marine mammal species from biotoxins have been noted in different regions of the globe, including Alaska and Kamchatka. To the best of my knowledge, no one has done any analysis of biotoxins in dead seals or the presence of microalgae species capable of producing such toxins in the Caspian. I cannot completely eliminate a military cause. But toxic fuel is indiscriminate and in that event we would not only see dead seals, but also birds and other animals.

What next for the seals?

The simultaneous death of more than 2,500 animals, mostly pregnant females, is a severe blow to a rapidly declining species, the population of which, according to the IUCN, has fallen to 70,000 animals. In the long term, however, the Caspian seal’s extinction could be caused by complex, chronic causes. Kazakh experts name such factors as reduction in food supply due to intensive fishing and the interception of nutrients trapped in Volga River hydropower reservoirs, chronic pollution and disturbance, poaching and bycatch in fisheries, epizootic diseases, habitat loss as a result of the shallowing of the Caspian Sea, and the development of oil fields. Most of these factors are exacerbated by climate change, to which cold-water loving and ice-dependent seals are extremely sensitive.

Regardless of the accuracy of the Latynina-Svitan hypothesis, Russian aggression against Ukraine is hardly a decisive factor in the fate of the Caspian seal as a species. The war does, however, exacerbate problems. Planning for species conservation is also hindered by a lack of monitoring and international coordination, and the war further undermines its establishment and financing.

After the recent die-off, a number of bureaucrats promised decisive conservation measures for the seals:

- Expanding and deepening cooperation with neighbors, a challenging task given the new geopolitical realities;

- Monitoring of seal bodies that wash up along shorelines, including timely analysis of the causes of death; this work is already underway in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, but not in Russia;

- Establishing rehabilitation centers for sick and injured animals, something that is unlikely to solve any significant problem other than disbursement of funds.

Creating an international protected area to protect marine ecosystems, including seals, aligns with recommendations made by IUCN and researchers from neighboring countries.

Figure 3. Map of the recommended state nature reserve for protection of the Caspian seal population in the Kazakh part of the Caspian sea. Source: Baimukanov, M.T., Ryskulov, S.E., Baimukanova, A.M. “On the need to approve a National Plan of Action for protecting the Caspian seal (Pusa caspica)”. Ekosfera Information and Analytical Journal. 2022. №9, pp. 31-34.

The protection of key seal habitats is an important undertaking, one that has been promoted for many years by Kazakh scientists who have created maps of areas requiring priority protection. Undoubtedly, a network of marine protected areas is also needed in the Russian sector of the Caspian Sea, including what was once also home to the richest commercial seal haulout – Tyuleniy Island. The IUCN Commission on Marine Mammals has identified areas important for breeding, molting and resting, feeding and migration of Caspian seals as a focus for international coordination. Properly organized, the creation of protected areas has the potential to help to save the species. Any protection regime must account for and prevent a variety of potential negative impacts on seals, including those that are less likely or not yet obvious. It is clear that the precautionary principle is most important for nature conservation. The management regime of a future protected area should include a ban on the flight of military aircraft over its water area.

Main image credit: kaspika.org

Comment on “Seals: Victims of war, greenhouse gasses, or asphyxiation caused by commercial fishing?”