Viktoria Hubareva

Translated by Alastair Gill

Ukrainian journalists studying the impact of the war on the environment visited eight protected zones in Ukraine and have also spoken to staff from those that are currently under occupation. The consequences of the war are being felt both on the frontline and in occupation, as well as in national parks and reserves located far in the rear.

There are no fewer than eight UNESCO biosphere reserves in Ukraine. These are areas which have international protected conservation status and are especially valued for their landscape, geological composition, and flora and fauna. Another reserve, which covers almost the entire Chornobyl exclusion zone, has intermediate status. It meets almost all criteria, except one – there are no people living within it, a mandatory criterion for reserves. Viktoria Hubareva tracked and analyzed the patterns and problems which have appeared in these protected areas since the full-scale invasion.

War has changed – and so have the ways of recording its consequences

Two of Ukraine’s UNESCO biosphere reserves – Askania-Nova and the Chornomorsky (Black Sea) reserve – are currently under occupation. In spite of this, however, the former was able to continue in “Ukrainian mode” (with financial and resource support from Ukraine) for a year after it was occupied. Although the occupation meant the reserve was unable to receive its allocated budget, the conservation body received financial support from other Ukrainian public organizations. This state of affairs lasted until the appointment of a Russian administration in spring 2023.

Askania-Nova’s animal collection is under threat of destruction. Today most of the reserve’s staff have been evacuated to Ukraine-controlled territory, and it is only possible to keep track of what is happening in the reserve by studying satellite images.

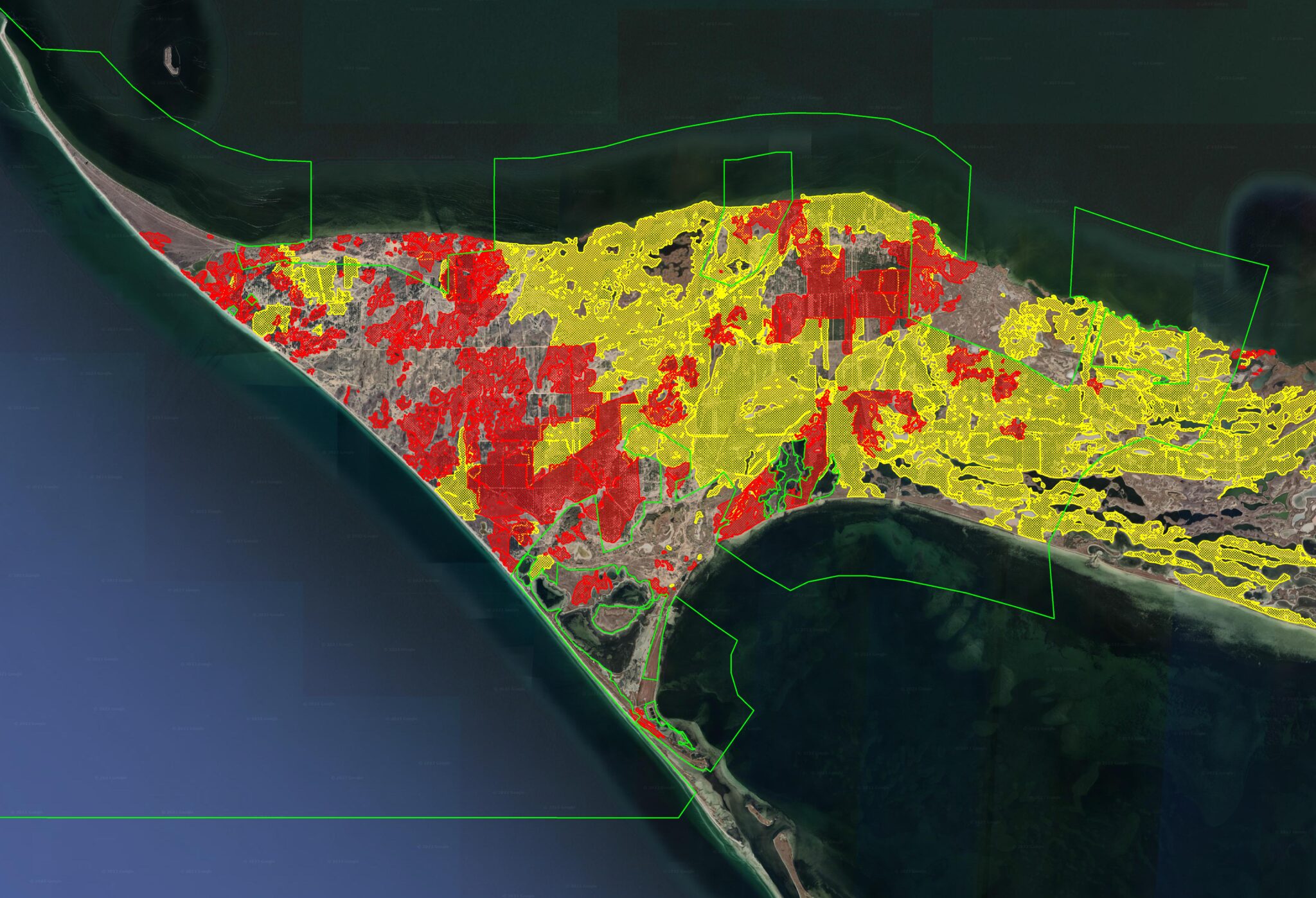

This method is also being used to record the consequences of the war on the environment in the Biloberezhia Sviatoslava National Nature Park, part of the Chornomorsky Biosphere Reserve. Despite the fact that the territory of this national park, which forms part of the reserve, is currently occupied, the park’s administration and research department are continuing their work from Ukrainian-controlled territory.

By using earth remote sensing technology, using data supplied by the European Space Agency and the U.S. National Geological Service, scientists can remotely record fires, flooding, various kinds of pollution and soil damage. The resulting analytics help to establish the precise causes for changes to the composition of biodiversity in a given area. This data is collected not only for the Biloberezhia Sviatoslava National Park, but also the Chornomorsky Biosphere Reserve, since they share common ecosystems.

Scientists have been gathering analytical data on the state of the environment since the first days of the war. They have taken on this vitally important mission to monitor the environmental impact of the invasion with the goal of bringing Russia to justice for ecocide at an international level.

Further field studies, which will be carried out after the liberation and demining of the occupied territory, will provide more information about the damage inflicted by the war, though there is already one example of a liberated reserve in the country where scientists have begun research.

What will happen in liberated protected areas?

The Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve offers an example. In the very first days of the full-scale invasion, Russian troops entered Ukraine through the reserve on roads from Belarus, which borders the reserve. Although the occupation lasted a relatively short period of time in this area – from February 24 to April 2022 – the consequences of the military presence were significant.

The most obvious of these were the construction of fortifications along roads, looted scientific research equipment and stolen, damaged or destroyed vehicles. In addition, more than 30,000 hectares of land in the reserve were damaged by fires, including 18,000 hectares of forest.

During the occupation, the Russians prevented these fires from being put out – they simply banned firefighting equipment from leaving the city of Chornobyl. Firefighting efforts are now complicated by the potential presence of mines in these areas. Furthermore, when Oleksandr Borsuk, head of the flora and fauna laboratory in the reserve’s scientific department, showed us the sites of the largest fires of 2022 on the map, we noticed that most of them began right on the border with Belarus. It is quite possible that all this is a consequence of enemy sabotage.

Studies on the impact of the war on ecosystems in the reserve have already begun. Research is now being conducted here into the processes through which plant growth returns to belligerative landscapes, areas impacted by the preparation and conduct of combat operations. This will make it possible to use the findings for the analysis of more seriously damaged areas that have suffered not only from the war, but also from resource extraction. This knowledge will enable scientists to make forecasts for the restoration of these areas and plan appropriate measures.

Protected natural areas located near the combat zone

What is happening directly near the frontline is clearly demonstrated by the case of the Desniansko-Starohutsky National Nature Park, which contains the core of the Desniansky Biosphere Reserve. It has suffered enormous damage as a result of the war, since the entire territory of the reserve is shelled almost daily by the Russian armed forces – the reserve runs along the Russian border for 30 kilometers. In June 2023 a Russian sabotage and reconnaissance group killed six workers from the Svesky forestry plantation, who were driving along a forest track in a jeep seven kilometers from the border.

Until mid-2023 the national park’s administration was located in the town of Seredyna-Buda. The town’s administrative boundaries hug the Russian-Ukrainian frontier. Last summer, the park’s administration building was destroyed. To protect its workers and property, the Desniansko-Starohutsky National Nature Park moved to the city of Shostka, and there are now almost no people left in settlements near the park. There is almost no electricity and no shops or other essential amenities.

However, despite the direct threat to life in the park, the reserve’s anti-poaching unit continues to operate, the scientific department continues its work remotely, and the environmental education department runs events for young people in safer areas.

In 2023 the Desniansko-Starohutsky National Nature Park team won an IUCN WCPA International Ranger Award. This is an international award for rangers, including Indigenous, community, and volunteer rangers, as well as those working in protected areas and reserves. Put simply, it is the most prestigious international award for those working in the conservation sphere.

According to park director Serhii Kubrakov the prize consisted of a grant, which was spent on purchasing equipment for patrolling the park. Despite having to work in extremely dangerous conditions, the park’s staff have no intention of quitting and are continuing their important mission.

- Read more: Protecting the environment in times of war. An Interview with environmentalist Yehor Hrynyk

Why are national parks and reserves away from the combat zone suffering from the war?

There are three reserves in the west of Ukraine. Two of them – the East Carpathian and Rostochya reserves – are transboundary; the third – the Karpatsky (Carpathian) Biosphere Reserve – has no foreign “neighbors”. All of them are located deep in the rear, so they have been unaffected by the direct effects of the war, such as fires resulting from shelling or sabotage by Russian soldiers. Nonetheless, this does not mean that these reserves have been unaffected by the war.

Even before the start of the full-scale war, conservation areas in Ukraine struggled to find financing. A significant part of their income came from tourists: many Ukrainians would visit the Carpathians as part of their vacation.

Now, however, it is the proximity of protected areas to the border that is now the primary obstacle to visiting reserves on the Ukrainian side. For example, all visits to Uzhansky National Nature Park, which is part of the East Carpathians Biosphere Reserve and borders Poland and Slovakia, must be coordinated with the state border service. This is one of the reasons for the fall in visitor numbers.

Inna Kvakovska, the park’s deputy director, says that only three-four of the park’s 17 eco-trail routes are currently accessible. The rest are closed due to the ban on visiting border areas, meaning less income for the park. The lack of funds is felt even more keenly for the reason that financing environmental institutions for the state during war is a very low priority, and unfortunately the money often runs out before they get their turn.

The Boikivshchyna National Park, which is also located on the border, is in a similar situation. Permission to visit the source of the Sian River, along which the Ukrainian-Polish border runs and where one of the park’s eco-trails lies, must be coordinated with the border service. Tourists need to obtain special permits and can only move around in the area when accompanied by military personnel.

A similar problem exists in the “neighboring” reserve, situated a little way to the north. Although the Yavorivsky National Nature Park, which is part of the Roztochchia Biosphere Reserve, is located a long way from the combat zone, two of its recreational areas are located in the buffer zone, in the Yavorivsky Base for Military Training. As a result, the Roztochchya zone has essentially been vacated and is closed to the public most of the time. And it is also difficult for tourists to visit Vereshchytsia, a recreational area boasting vacation homes, an environmental education center, and lakes. Although the area is still partially open to visitors, the human factor comes into play. Few people are interested in admiring nature in a place where there are audible explosions and risk of an enemy missile strike.

Around 80% of those employed by national parks and reserves earn the minimum wage, meaning they receive less than EUR 200 each month. Yavorivsky National Nature Park does not have the funds for bonuses, additional payments, and supplements. Previously, the park had a regular staff turnover, with employees coming and going, but the outbreak of the war saw a significant outflow of personnel. It is almost impossible to replace employees, resulting in staff shortages, making it impossible for these conservation institutions to carry out their work fully.

The frontier zone has grown to two kilometers in width, including in protected areas on the border. In February 2023 Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada passed a law to facilitate this, which the UWEC Work Group has previously covered. The lands were withdrawn from the Natura Reserve Fund and transferred to the Ukrainian state border service. This creates a risk that animals will not be able to move along their migration corridors, which cross through the entire transboundary reserve, and of which there are many in protected areas.

As we have seen in this article, the war is having an impact on conservation areas throughout Ukraine and at all levels, from the direct damage caused to the ecosystem to the inability of national parks and reserves to carry out their direct responsibilities for various reasons.

At the political level, high hopes are being placed on the reparations that Ukraine should receive from Russia after the end of the war. These resources can be used to restore ecosystem services and finance environmental institutions. However, it is already clear that painstaking work on demining must be carried out before the restoration process can begin, and unfortunately national parks have been given the lowest priority for demining.

However, there are also positive aspects. Ukraine is now gaining invaluable experience in recording the consequences of war on the environment, and through cooperation with foreign partners, law enforcement agencies, public organizations, scientists, media and even individual communities, the country has gained a unique asset that will allow us to find solutions to similar problems around the world.

Main image: Forest in the East Carpathians Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. In the foreground is the Ukrainian part of the reserve, beyond it the Polish sector. Photo: Mykola Tymchenko.

Please correct my name in this article. Not Alexander Barsuk, but Oleksandr Borsuk.

Names should be transliterated not translated with moskovite bias.

Thank you for your comment. We corrected your name.