by Viktoria Hubareva

Translated by Alastair Gill

Experts have been studying the direct and indirect environmental damage caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine since the very beginning. However, new aspects of the conflict’s disastrous influence on the environment continue to emerge. To mark World Environment Day on 5 June, experts from the UWEC Work Group made a series of reports in a webinar titled “The Natural Cost of War”, held by the University of New South Wales (Canberra, Australia).

The seminar was led by the environmental philosopher Anthony Burke, who is well known for his work on the establishment of international environmental law and supervisory institutions.

Watch a recording of the seminar, or familiarize yourself with the main points made by the speakers in this article.

Protected areas in Ukraine may lose their value

Environmentalist Oleksii Vasyliuk, head of the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, talked about the challenges now facing nature reserves, national parks, and other protected areas in Ukraine.

“There is a small number of protected zones in Ukraine, covering around 6.8% of the country’s total land area,” said Vasyliuk. “Around half of them — 44% — are either located in occupied territory or have suffered from military activity. Unfortunately, this is very relevant for the most valuable and oldest protected areas.”

“However, we can safely increase this figure, since in fact there are more protected areas in Ukraine. The fact that they are not yet under legal protection in Ukraine is just down to a gap in the legislation,” he explains.

“Ukraine has numerous sites within Europe’s Emerald Network, which provides international protection, although they still haven’t received conservation status within the country. All these territories have also suffered greatly, but we still don’t have a legal mechanism for their restoration. We’re doing all we can to adopt the necessary legislative acts that will protect these areas in the future.”

At the same time, many protected areas are still under occupation. Drawing an analogy between these territories and those already liberated, Vasyliuk explains that in protected areas temporarily occupied by the Russians, the entire administrative infrastructure has been destroyed.

“On top of that, all of this land is mined, which prevents national park employees from carrying out their jobs. In territories still occupied, conservation activity has completely ceased,” he says, adding that the war is inflicting immense damage on biodiversity. “The war has affected rare plant, animal, and bird species, a number of them super-endemic species. Often, 100% of their populations were located in a combat zone, and we can’t be sure that they haven’t almost – or even completely – disappeared.”

Assessing environmental damage

According to Vasyliuk, it is almost impossible to fully assess the war’s environmental damage, given that it is not feasible to carry out the necessary research and analysis while hostilities continue. We will only be able to reach final conclusions after the end of the war and the complete withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine.

“There’s a high chance that the work will be less about counting quantifiable losses, than about recording environmental changes, work that is necessary in order to understand what actions are important for preventing catastrophic consequences,” he explains. In his opinion, this will make it easier to carry out a financial assessment of the damage inflicted.

“Right now,” says Vasyliuk, “It is important to concentrate on already liberated areas, prioritizing soil testing to find out if it is safe to use.

As for national parks, now is an optimal time for them to send their employees to other countries on experiential exchanges, bringing that learning home to Ukraine.

“In fact, there could be far more solutions — I’ve only named the most obvious scenarios for how things might develop,” he said.

Who should help preserve the most valuable ecosystems until the state takes concrete action?

Vasyliuk points out that landscape changes due to explosions and fire, destruction of ecosystems, and the scattered remains of abandoned military equipment have stripped many of Ukraine’s national parks of the value that previously justified their conservation status.

Although compensation mechanisms for environmental damage resulting from military action are yet to be fully worked out, Ukraine already has a solution to the problem. Vasyliuk sees assistance from public organizations to national parks and reserves as vital. This was the principle over the last year that guided the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group to support Askania Nova Biosphere Reserve, under occupation since the full-scale invasion began. This unique case demonstrates the ability of such community organizations to support nature conservation institutions. Vasyliuk believes this experience will be invaluable in the future to both help create new nature conservation areas and restore those damaged by the war.

Can war inflict indirect harm upon the environment? Yes, if it’s a 4,000-kilometer wall that effectively creates an animal reserve.

During the webinar, UWEC Work Group expert Eugene Simonov, an environmentalist, specialist in the conservation of freshwater ecosystems, globalization’s impact on the environment, and international cooperation among conservation organizations spoke about the indirect harm inflicted on the environment by war “behind the scenes in the military theater.”

The very real environmental consequences caused by increased extraction of natural resources or large numbers of refugees passing through an area are good examples of such damage. The most vivid example, in Simonov’s opinion, is the construction of a barrier stretching 4,000 kilometers along the borders between Eastern Europe’s EU member states and Russia and Belarus. This barrier is being planned as a defensive measure to protect these countries from Russian and Belarusian aggression.

Approximately 240 km of the barrier have already been built, a section that passes through a vast forest called Bielaviežskaja Pušča, on the Belarusian-Polish border.

“The harm caused by this structure is clear, since the barrier blocks animal migration and interbreeding of individuals from different populations. In addition, electrified barbed-wire barriers can also be deadly for animals. This is a big problem with big consequences,” says Simonov.

The war has created risks to global food security

The outbreak of war forced Ukraine to close some ports and abandon some means of transporting grain, and as a result logistics companies were obliged to find alternative routes through new areas. However, the use of areas of high-conservation value to compensate for the lack of grain and fertilizers carries certain risks.

“Under the pretext of transporting food to Europe through the Danube [Delta Biosphere] Reserve, which is located on both Ukrainian and Romanian land, a new transport corridor was built, one which could cause irreparable damage to the environment,” explains Eugene Simonov.

In addition, complications with Ukrainian and Russian exports increase the risk of famine and increase the likelihood of over-exploitation of natural resources.

War is a convenient tool for ‘promoting’ political decisions detrimental to environmental protection and depriving civil society of mechanisms to react.

Even the indirect environmental effects of the war impact the political sphere. According to Simonov, this manifests itself in the weakening of legislative and other socio-economic mechanisms. The results are manifold: postponement or cancellation of previously adopted environmental programs, loosening of environmental and technological standards, exploitation of previously protected areas and rare species’ habitats, allocation of subsidies for hazardous and environmentally harmful activities, termination or slashing of funding for environmental and climate programs, management of environmental laws, and finally, suppression of civil society and dissent.

War can weaken the need for businesses and municipalities to follow environmental requirements and creates new incentives for activities harmful to nature. Most of the examples cited by Simonov relate to Russian and Belarusian domestic politics, where the tiny segment of civil society that could oppose such decisions is actively suppressed.

“Cases of activists being criminally prosecuted have become more frequent in Russia. You can now be charged with criminal and/or administrative responsibility for both environmental and anti-war activities. Dialogue with government and business has become even more difficult,” says Simonov, pointing out that this is not limited to Russian entities — international environmental public organizations have also been declared “foreign agents” or “undesirable” in Russia.

While not on the same scale as in Russia and Belarus, other countries are also seeing a weakening of environmental legislation and reduced opportunities for civilian oversight, including Ukraine and EU member states.

New testing grounds and a 21st-century arms race

Some countries, with an eye on the war in Ukraine, are beginning to increase their military production capacity, creating another challenge to the environment. According to Simonov, this mostly concerns European states, though it may not be limited to them alone.

In his report, Simonov drew attention to the fact that important natural areas in Ukraine and Russia are now being used for military drills and tests, underlining that military activity and a new arms race not only deplete resources needed to protect nature, but also lead to an increase in pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

War and the climate

Environmental journalist and UWEC co-editor Angelina Davydova, an observer for the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) since 2008, member of the World Future Council and co-host of the English-language podcast The Eurasian Climate Brief, spoke about the link between war and the global climate agenda.

According to Davydova, the global green community had high hopes that sanctions on Russian fossil fuels would draw the world’s attention to the necessity of reducing dependence on oil, gas and coal producers, and that sanctions should actually accelerate decarbonization efforts.

“But what did we see last year? What happened in the short term? Many countries have simply switched to other sources of fossil fuels from other suppliers. And if you look at the statistics and company reports over the past year, you’ll see that oil and gas companies around the world have actually increased their profits dramatically. Obviously, this is bad news for the climate,” she explained.

However, Davydova did stress that this is only a short-term effect. In the future, she explained, more efforts will be directed to the development of renewable energy sources and additional decarbonization measures, including energy and resource efficiency, and that this should bring positive results.

One indirect result of the war is that some countries have resumed the use of coal-fired power plants, and some individuals have partially returned to heating houses with wood. This is a step backwards, since it is likely to lead to greater deforestation.

Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant reveals the weaknesses of international agreements

Professor Anthony Burke devoted his brief report to nuclear safety issues at civilian sites and the reform of international law. He recently published an article about this, featuring an analysis of the situation in Ukraine.

Burke qualified his conclusions by pointing out that it is currently extremely difficult to improve international treaties, especially given that members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) (which includes Russia) have the right of veto.

The August 2022 five-yearly review conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons was fractured by division and ended in a stand-off. Russia blocked the adoption of a draft outcome document that would have strengthened the treaty by considering, for the first time, the safety and security of nuclear-power plants in armed conflict zones, including Ukraine.

Nevertheless, the most urgent priority is the withdrawal of Russian military personnel and weapons from the Zaporizhzhia NPP, and ensuring that there are no further attacks on it. The IAEA’s call for the demilitarization of the Zaporizhzhia site (so called “seven pillars” or “five principles”) is consistent with the Geneva Conventions and should be enacted urgently. Professor Burke believes that those principles still could be incorporated in international law despite difficulties.

Burke also noted that if there is a nuclear incident at the plant, then Russia will lose its place among the family of civilized nations forever.

Russia missing the opportunity to be an international environmental leader

The last speaker in the webinar was Freya Matthews, an Australian philosopher from La Trobe University. Matthews talked about why she had chosen to write an open letter to Vladimir Putin in December 2022, titled “On Greatness”. The essence of her message was to show that the ways in which Russia is trying to assert itself in the international arena through military force are catastrophically outdated, and the “greatness of nations” in today’s world depends on what they can offer humanity in the way of a contribution to our collective survival and cooperation with nature. In this respect, Russia has great potential and significance.

But it is clear that Russia today is doing everything in its power to undermine any hopes that it can play a leading role in the future.

How can I find out more about the consequences of the war for the environment?

As we can see, the environmental consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are not limited to the war zone – they touch the whole world. Experts are recording new aspects of the impact of military operations on the environment.Of course, one webinar cannot tell you everything about the environmental consequences of the war. To facilitate free access to information on the topic, UWEC Work Group has created a catalog of over 50 resources to help keep track of the environmental situation and the consequences of the war.

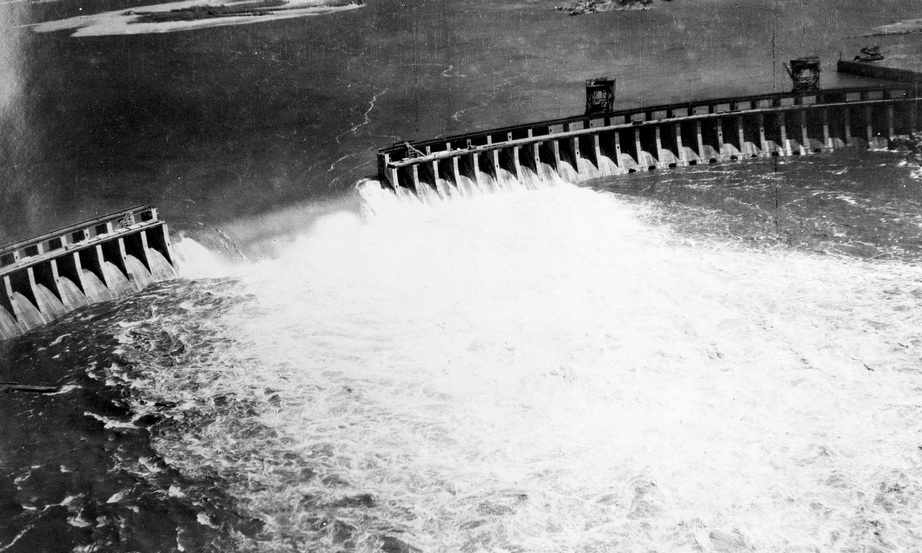

Main image source: UNSW Sydney

Comments on “500 days of war: Experts discuss the war’s environmental impacts”