By Oleksii Vasyliuk and Eugene Simonov

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Dam-based hydropower plants (HPPs) present risks in both wartime and peacetime. Today, the main site of concern in Ukraine is the Dnipro hydropower cascade (whose reservoirs supply two-thirds of the country’s population). A breach of just one of the cascade’s dams could provoke a humanitarian catastrophe, loss of life, and large-scale destruction. In this article, we will analyze military aspects of the risks of hydropower.

Figure 1. 12 October 2022 flooding in Kyiv caused by a high-volume water release (while maximizing electricity generation) at Kyiv Hydropower Plant. Source: “Киев Ирпень Буча” channel on Telegram.

Large hydropower in Ukraine

To date, ten hydroelectric power plants with large dams have been built in Ukraine, including the Dnipro cascade of six dams and hydroelectric power plants (HPPs) on the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Terebla Rivers (total installed capacity – 4,730 MW), as well as three pumped storage hydropower plants (with a capacity of 1,487 MW). Although these plants represent just 11% of energy sector capacity, they are important for the power grid as a source of flexible power to cover peak loads.

Judging by the proceedings of the July 2022 Lugano, Switzerland meeting to discuss Ukraine’s post-war restoration, hydropower has so far suffered the least military damage in the power sector. Additionally, only 7% of hydropower capacity is controlled by Russian invaders, foremost of which is Kakhovka HPP, where only three of six turbines are currently operational. Ukrhydroenergo filed a claim with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) against Russia, seeking damages for the destruction of two units of Kakhovka HPP, as well as for an unfinished wind power plant on Zmiinyi (“Snake”) Island, in the amount of UAH 17 billion. For comparison, over 90% of wind power stations were under occupation in June according to Ukraine Recovery Conference Materials.

Another hydropower plant on the Oskil River (capacity 4 MW) was blown up to slow the Russian army’s advance on Kharkiv and is once again under Ukrainian control. Unfortunately, the destruction of this particular small hydropower plant is quite important for residents in Eastern Ukraine. It is the Oskil Reservoir that maintains a stable water supply across the entire Donbass region.

Despite relatively “minor” known losses to date, it should not be concluded that a hydroelectric dam is the most trouble-free energy utility in wartime. Dams and dikes have been used as weapons of mass destruction throughout the history of the world, sometimes with horrendous consequences comparable to the result of atomic strikes or carpet bombings.

History near and far

The most destructive flood in history was the demolition of a cascade of dams on the Yellow River on 9 June 1938 during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The freed river rushed into the old channel, flooding 70,000 km2 and killing between 500,000 and 800,000 civilians in rural areas, while another 3 million became refugees. Following in the footsteps of ancient hydraulic warriors, General Chiang Kai-shek sought to cut enemy communications, but he did not succeed, and his new capital Wuhan fell three months later.

The most tragic peacetime accident was the 1975 destruction of the Banqiao Dam in the Chinese province of Henan by a flood. Water from the bursting Banqiao Reservoir demolished 62 dams downstream. In total, 26,000 people died as a result of the flood, with another 145,000 dying immediately after due to famine and epidemics. 5,960,000 houses were destroyed.

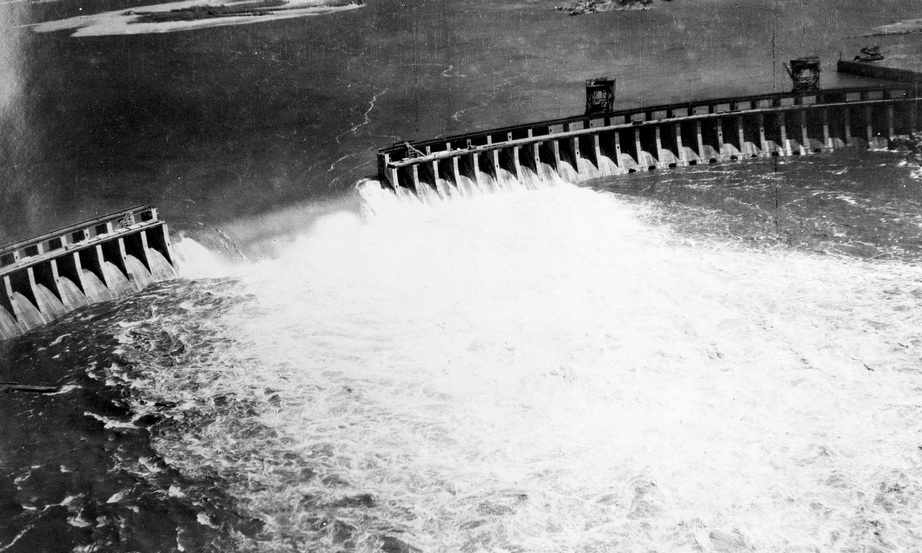

Figure 2. Dam breach at Dnipro Hydropower Plant during WWII. Source: Bessmertny Barak.

Ukraine’s own historical experience reinforces and increases modern fears. The blasting of Dnipro Hydropower Plant (HPP) by Soviet troops during World War II came as a surprise to contemporaries. Ukrainian historians point to significant casualties among civilians and retreating Soviet units (largest estimate is over 100,000 people, see video). The dam’s bombing during the Soviet army’s retreat has always been perceived as a tragedy. Even the recent limited flooding of the Dnipro River’s banks in Kyiv resulting from the intensive discharge of water from the power plant on October 12 caused a flood of complaints from concerned citizens.

Downstream residents are unconvinced by Ukrhydroenergo’s official statements that “dams designed and built in the 1960s with a significant margin of safety and stability against (military) threats – massive hydraulic structures – are not easy to destroy or significantly damage using a missile.” And the public threat that the company “views the dissemination of unfounded assessments of catastrophic consequences caused by a hypothetical breach of the Kyiv hydroelectric dam as dubious, inappropriate, and even potentially harmful activity aimed at whipping up panic…” leaves no doubt that the the company believes the best way to solve the problem is stop discussing it.

In any case, the destructive power of water stemming from the destruction of dams, is firmly embedded as a military tactic in the consciousness of many people. Even classical works of literature (from the world-famous books of J. R. R. Tolkien to Ukrainian literary classics such as “The Raven Eagle,” by I. Frank ) have a wealth of final battle scenes in which the battle’s outcome is decided by the breach of a dam.

Current “achievements”

Attacks on dams began in the early days of the Russian invasion. As early as 26 February, Russian troops tried to seize the dam at Kyiv Hydropower Plant. When the attack was repulsed by Ukrainian armed forces, it was then targeted with the first missile attack, although the missile did not reach its target.Despite the fact that hydroelectric dams have shown some resistance to high-precision missile attacks, they remain among the highest priority targets, since breaching them can radically change the operational situation on the battlefield and undermine enemy morale. This was the reason for Russian attacks on the relatively small dam at Karachuniv reservoir in Kryvyi Rih on 12-13 September. To date, this is the only known case of a successful missile attack on a dam. Analysts list several goals for this type of strike: partial flooding of the city, depriving residents and the most powerful metallurgical industry (at that time) of water supply, or hindering Ukrainian troops crossing the Inhulets River where a counteroffensive was happening in southern Ukraine. The damage was repaired within 48 hours. Our analysis of Sentinel satellite imagery showed that the water level in Karachuniv reservoir did not fall as a result of these events.

Figure 3. Flood modeling at Karachuniv reservoir. Source: ОСНА.

Modeling showed that, at worst, the dam’s breach would flood a few districts of Kryvyi Rih. Damage is limited when there is only partial destruction of the structure and timely repairs follow in comparison to what can be expected in the event of a complete breach of the dam.

Figure 4. Repairing Karachuniv dam. Source: International Journal on Hydropower and Dams

Repeated rocket fire by Ukrainian armed forces on Kakhovka HPP’s bridge (captured by Russian troops) seems to confirm Ukrhydroenergo’s confidently optimistic assessment of dam resistance to rocket fire.

However, the dam’s destruction is not likely to be on the Ukrainian armed forces’ agenda – they are planning to use it to cross over to the left bank of the Dnipro River. For example, in August, Ukraine’s armed forces used high-precision missile strikes to destroy the bridge over Kakhovka HPP’s shipping lock, a move which made it difficult to transport goods, but did not affect the integrity of the dam in any way.

Figure 5. Four temporary crossings over Kakhovka HPP’s navigation canal were installed by the Russian armed forces after the main bridge was destroyed by missile strikes. Source of video: War Happens.

All other major breaches of dams and dikes (e.g., those that occurred at the mouth of the Irpin and on the Oskil and Zherebets Rivers) were the result of deliberate damage caused by retreating troops (as was the WWII breach of the Dnipro HPP dam). As recent events on the Crimean Bridge have shown, large-scale damage to infrastructure can be carried out well behind the frontlines.

The Kherson region’s pro-Russian administration actively accuses the Ukrainian armed forces of seeking to destroy the Kakhovka HPP dam.

But targeting this dam is more likely to be considered as a move made by the retreating enemy. According to the Ukrainian government, in October, long after the Russia-controlled Kakhovka hydroelectric dam was mined, the Russian Federation began an active information campaign about the “horror” of a possible large-scale detonation of the dam during the fighting for Kherson and encouraged the local population to move from the right bank of the Dnipro River to Oleshky and Golaya Prystan on the left bank. Meanwhile, in the event of a dam explosion, it is precisely these areas of the left bank, located in the floodplain, that will suffer the most from flooding. In addition to those settlements and numerous riverside summer villages, Oleshkovskie Pesky National Nature Park and a section of the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve may also be affected.

Figure 6. Russian social media are actively circulating a video simulating flooding in the event of the Kakhovka hydroelectric dam being breached. Source: “Kyiv Irpin Bucha” Telegram channel.

The testimony of many experts and our analysis show that total destruction of the dam is not beneficial to either side, while propaganda exploitation of the threat of its detonation is much more beneficial to the Russian side. In particular, media sources insist that draining Kakhovka Reservoir will cause a catastrophe, leaving Zaporizhzhya NPP without cooling.

Post-Fukushima stress tests undertaken across Europe in 2011 indicated that, despite the fact that draining the reservoir will reduce the long-term reliability of the water supply system, the level of the ZNPP’s autonomous cooling pond (containing over 40 million cubic meters of water) will remain unchanged in the medium term. Experts also note that now that the Zaporizhzhya NPP is shut down it has minimal water needs.

At the same time, a panicky atmosphere connected to the threat of “breaching the hydropower dam” could allow the rotation of Russian troops under the cover of civilian migrants, and in the event of a retreat, even without the total destruction of the dam, the Russian Federation can completely disrupt transport links across the river or halt electricity generation at the HPP.

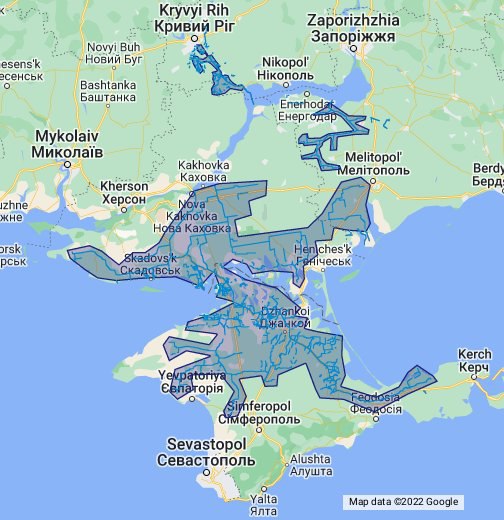

In the case of the dam’s total collapse, the flood will wash away areas of the left bank occupied by the Russian army, and a drop in the reservoir’s water level by just four meters will end water supply to the North Crimean Canal.

Figure 7. Irrigation and other water supply areas dependent on Kakhovka Reservoir are predominantly located on currently Russia-occupied lands. Source: Analysis and graphics by Valeria Kolodezhna/UWEC Work Group.

That said, there is a significant risk that events will not proceed logically and or in the objective interests of the parties. This means that the danger of the dam being destroyed by the warring parties will remain until the end of the war.

Figure 8. Russian National Guard sentry at Kakhovka HPP. Source: RIA Novosti.

Nuclear escalation

In September-October, threats to destroy large dams achieved a “nuclear phase” in propaganda terms. The Russian media repeatedly accused Ukraine of intending to blast Dnipro HPP once again. It is clear from the coverage, however, that this is not even a Freudian slip, but an outright threat.

On 5 October, Moskovsky Komsomolets published an interview with Alexander Komarov, an expert and director of the Explosion Resistance Scientific and Technical Center at Moscow State Civil Engineering University. The article attempts to expose all the insidiousness of the “provocation planned by Ukraine and the United States,” stating that “Hydroelectric power plants are, in principle, vulnerable. Dnipro HPP, of course, cannot withstand a nuclear strike; it will collapse. A giant wave of water will rush downstream – a significant disaster. If a single HPP in the cascade collapses, the domino effect will likely result in all downstream dams starting to fall as well …. ” The most unpleasant aspect is that this assessment is plausible, and explains in a veiled fashion what will happen if nuclear weapons are used by the side that possesses them.

At best, this campaign across dozens of Russian media outlets is simply an attempt to sow panic in cities along the Dnipro River. At worst this is a public warning about a possible course of events.

Accidents foreseen in plans and described in textbooks

The potential danger of breaching Dnipro HPP or other dams in Ukraine has been repeatedly discussed and during peacetime, relevant agencies invariably avoided the discussion, accusing worried scientists of alarmism. These same agencies have borrowed millions of dollars from international donors to repair the hydropower plant and its dams.

A detailed review by Rubrika of the consequences of a dam failure provides data on potential catastrophic flooding in the event of accidents at Kyiv, Kanev, Kremenchug, Dnipro, and several other smaller hydropower plants. The article correctly states that the public health and epidemiological damage of flooding is comparable to damage caused directly by the breakthrough wave, but delayed over time.

Data on those consequences in the context of Russian aggression are listed in a recent report on Ukraine’s water security. The article’s initial source is a pre-war textbook by Mikola Khilko entitled “Ecological Safety of Ukraine: a Study Guide” (2017 edition). Evacuation instructions in the event of a dam break are required to be posted on the websites of city administrations located downstream from the HPP. There is an example of such instructions listing areas subject to flooding in Zaporizhzhya in the event of a dam break at the Kremenchug HPP. One of the Zaporizhzhya websites also contains useful tips on what to do “if you receive information about a threat of flooding and evacuation”:

- “Go to a designated safe area or to an elevated area in the prescribed manner;

- Take documents, jewelry, necessities, food for 2–3 days;

- Move items from flooding to upper floors;

- Before leaving the house, turn off the electricity, water, and gas;

- Go to upper floors if it is not possible to evacuate. If the house is single-story, shelter in the attic. Climb a tree or a roof. Remain there until help arrives;

- If in the water, remove heavy clothes and shoes. Find nearby objects that could help you stay afloat;

- Signal to rescuers so they can find you faster.”

The likelihood of an accident involving the breach of each individual large dam in peacetime is relatively small, but is more than surpassed the many thousands of victims and destruction in the event of an “unlikely” accident. This phenomenon is best understood by the example of a nuclear power plant, when the consequences of just two accidents call into question an entire global industry with thousands of operating reactors.

The war exponentially increases the likelihood of such catastrophic events, rendering hydropower dams one of the most dangerous pieces of infrastructure for nearby residents.

Hydro’s many woes

Kateryna Hnedina and Pavlo Nagorny list the catastrophic consequences of accidents and terrorist acts at hydropower plants as a long-recognized major factor in dam vulnerability in an October 2022 article regarding the prospects for hydropower development in Ukraine. However, they (and many other authors) are much more concerned with a wider range of vulnerability factors and problems for HPPs and their reservoirs:

- The construction and maintenance of hydropower plants requires ever-increasing financial resources, primarily international loans, making hydroelectric power plants uncompetitive in comparison with alternatives;

- The time needed to construct new HPP and pumped-storage hydropower plant (PSHP) capacities is many times longer than for other types of electricity production;

- Local populations are critical of HPPs and actively protest their construction;

- With increased water pollution, accumulated reservoir effluents become foci for ecological catastrophe;

- Fragmentation of and changes in river ecosystems lead to the disappearance of fish and other aquatic organisms, including commercially important species;

- At the same time, reservoirs become hosts for the spread of dangerous non-native species of fish, mollusks, jellyfish, etc.

- Also, the lack of water flow leads to the large-scale development of blue-green algae “blooms” in reservoirs, which in turn leads to fish dieoffs; and

- Climate changes and intensifying droughts are already leading to a drop in HPP production, and this trend will only worsen.

Outside the war’s context, each of the above-mentioned “peaceful” problems calls into question the expediency of not only creation of new HPPs, but also extending the operating life of a number of existing facilities.

For Ukraine, water deficits due to climate change may be the last straw when it comes to future decisions. Knowing that total production and available capacity of hydropower will rapidly decline, construction of new hydroelectric dams is pure madness.

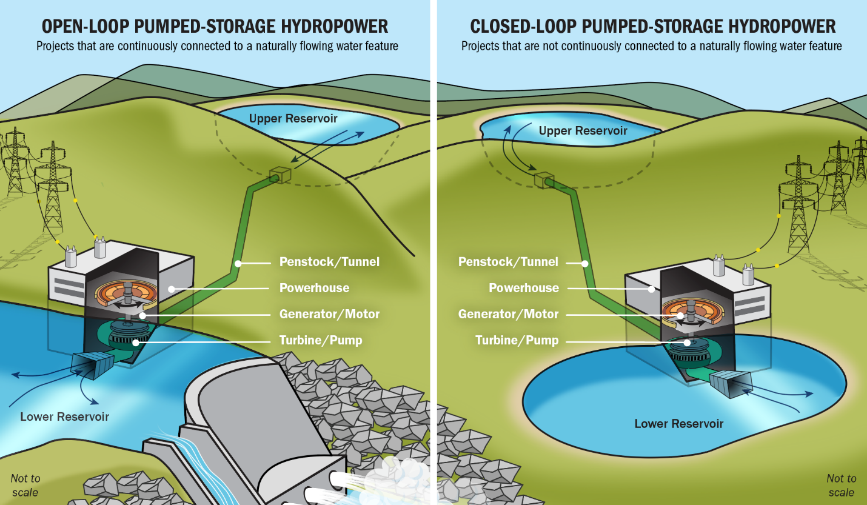

When it comes to climate change, Ukrhydroenergo director Igor Sirota sees salvation in the creation of pumped storage hydropower plants (PSHP) that are less dependent on water flow along the river. Judging by the interview, the creation of new HPPs is not a priority for the state-owned company in current conditions.

But all planned sites for new HPPs and PSHPs (based on Soviet-era plans) are located within either protected areas or historical and cultural sites. In all cases, the plans for construction or development of existing PSHPs in Ukraine are condemned by the expert community and public protest.

All existing and planned PSHPs in Ukraine assume the fragmentation of natural watercourses, while around the world less environmentally problematic “closed loop” PSHPs, where the upper and lower reservoirs do not obstruct rivers, are under active development.

Figure 9. The fundamental distinction between the traditional HPPs planned in Ukraine and other closed loop PSHPs is that, like hydroelectric power plants, open-loop HPPs assume the presence of dams on rivers. Source: PV Magazine.

Researchers from Australian National University published the “Global Atlas of Closed-Loop Pumped Hydro Energy Storage,” an analysis of the potential of PSHPs. The Atlas lists 616,818 sites suitable for “closed loop” PSHPs capable of storing 23 million gigawatt-hours of energy, an amount ten times greater than all the imaginable needs of the world’s energy systems. The Atlas’ creators attempted to avoid siting them within national protected areas, but emphasize that their results require detailed assessment of biodiversity impacts and social and cultural values, as well as a consideration of the current needs for energy system development in order to select locations suitable for further design.

Figure 10. The potential of closed-loop pumped-storage hydropower plants in Ukraine is relatively small due to a largely flat terrain. However, there are many alternative sites for PSHPs worth considering that are less dangerous than the three Soviet projects promoted by Ukrhydroenergo. Source: Global Atlas of Closed-Loop Pumped Hydro Energy Storage.

Another widely used alternative to the installation of new PSHPs is converting existing HPPs into PSHPs, mainly in connection with the replacement or installation of additional equipment. After modernization, HPPs acquire the ability to pump water from the lower reservoir back into the upper reservoir overnight for electricity generation during peak hours. In general, there are opportunities in the hydropower sector to consider new, more progressive technical solutions that both increase reliability and reduce social and environmental damage.

Wartime lessons for hydropower

The war has demonstrated the risks of large dam structures as dangerous infrastructure, whose destruction is possible in the course of bombings, battles, and sabotage. A significant part of Ukraine’s residents live along large dam-regulated rivers and are thus exposed to these risks. In addition to the material risks, the psychological impacts of large hydroelectric dams looming upstream are a powerful destabilizing factor for residents, especially in wartime. Russian propaganda actively makes use of this worry.

Of course, a large dam is a dangerous and problematic infrastructure even in peacetime, and its breach is only one of a dozen significant risk factors. Climate change will probably render the construction of new HPPs unlikely, and the continued operation of old ones will raise more and more questions in society. Water, rivers, and river valley landscapes are the most valuable public resource, with fierce competition between many types of use and environmental requirements. Consequently, river use for energy generation (something that can be produced in many other ways) conflicts with higher priority environmental and socio-economic goals.

In the present situation, Ukraine’s energy sector faces a complex and comprehensive transformation. In future articles, we will examine the questions the war poses for renewable energy in Ukraine and its energy sector, one that is rapidly integrating with the European market.

The Kakhovka dam gates were opened between October 6 to November 1, 2022. During this time (per Sentinel 6 altimetry data), the reservoir level went from a seasonal high of 16.58m (above MSL) to a 6 year minimum of 15.36m. The reservoir level typically has a minimum in the late fall and an annual peak in the late spring. The 1 meter lowering of the reservoir in a month was faster than any time during the altimetry monitoring period. What are the Russians doing?