by Victoria Hubareva

Translated by Alastair Gill

In September 2023, fires raged across Askania-Nova, a unique biosphere reserve in the south of Ukraine. What is happening now in this Russian-occupied reserve?

The Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve in the Kherson region has been under occupation since the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Founded by the assimilated German Friedrich von Falz Fein in 1898, the reserve is the oldest protected area in Ukraine. It was he, having noticed that sheep grazing was destroying steppe vegetation, who first decided to allocate an area that would fenced off from animals in order to preserve the natural condition of the land.

Over time, the reserve grew in size. It survived two wars and was later inscribed as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. When Ukraine gained independence in 1991, Askania-Nova retained its borders. Scientific research was conducted in the reserve and nature lovers could go on guided tours. The reserve lies on a migratory route for birds, and hundreds of thousands of different species of birds fly through the area every year. Askania-Nova also has an active rewilding program, repopulating the area with animals that for various reasons had disappeared from their habitats.

The reserve was taken over by the Russians in the first days of the full-scale invasion of 2022. Despite that occupation, the reserve managed to continue to function as a Ukrainian institution during the first 13 months of the war. Over that period, reserve management refused to cooperate with Russian occupiers, facilitating continued protections for the protected steppelands. The collections of zoo animals and plantings in the arboretum were also secured.

Since the beginning of the occupation, military equipment, troops, and occupation personnel have been stationed on the reserve. They build combat fortifications, and aircraft now constantly fly over its territory, a practice that is illegal for protected areas. All this has created and continues to create significant stress factors for animals and, of course, makes it impossible for the biosphere to carry out its normal work.

Read more in this article:

Russian administration and new risks

On March 20, 2023 the occupation authorities appointed their own administration and established effective control over the institution. This led to an increase in risks and removed all real levers of influence over the course of events and means of supporting the reserve’s collections through legal Ukrainian channels.

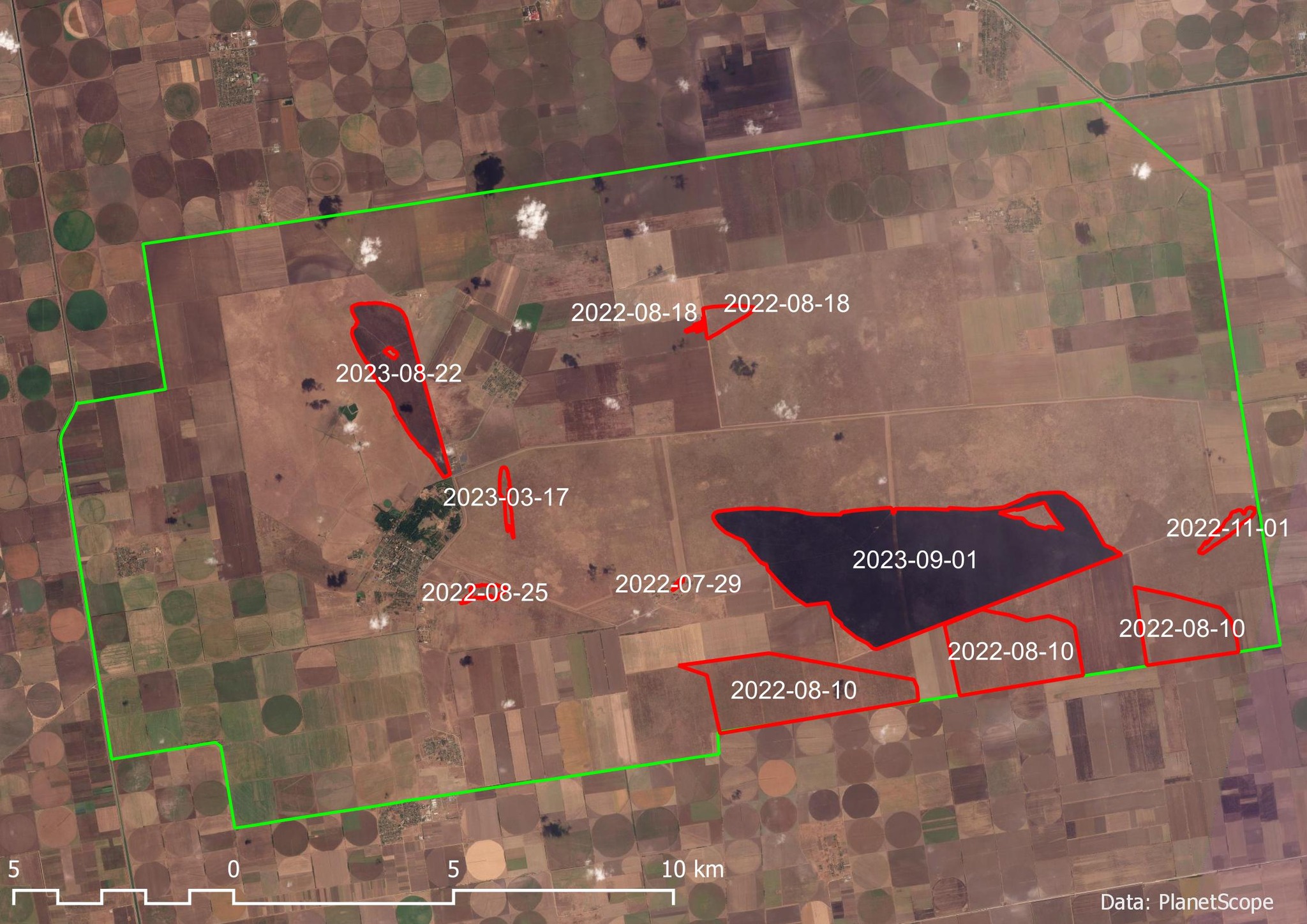

According to the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, fires in August and September 2023 created new threats. During the last of these, caused by a lightning strike on 1 September, 1,790 hectares of protected steppe burned, visible on satellite imagery. This conflagration was the largest to date since the occupation began.

Responsibility for the fire’s consequences and damage inflicted upon the protected steppe ecosystem lies entirely with the occupation administration. One of the biosphere’s specialists, who wished to remain anonymous, noted:

“Although the latest fire was caused by a lightning strike, its spread could have been prevented by a sufficient firebreak (200m in width), as prescribed by fire protection measures (in fact, a strip just 100m wide was mowed). According to eyewitnesses, the previous fire in the protected natural depression of Velykyi Chapel’s’kyy Pid resulted from a missile launch over the protected area from a Russian military aircraft, although the occupation administration promptly reported on discovery of ‘debris from an unknown artillery system of Ukrainian origin…’”

Russians are preventing contact with territories under their control – but reserve staff are still gathering information

Askania-Nova employees who have left for Ukrainian-controlled areas over the past year now collect information about the biosphere reserve remotely using satellite imagery. No specialists capable of carrying out direct visual examinations remain in the reserve.

Although some of the reserve’s personnel remain in occupied territory, Viktor Shapoval, director of the Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve, says most of these people are simply hostages of the situation:

The occupation administration threatens these people with pretty strict sanctions for the transmission of any information. However, we understand the general picture and the interruption to the institution’s activities. We obtain some data through remote monitoring (as in the case of fires, mowing, etc.). Meanwhile, the occupation administration, trying to claim credit for certain positive developments, publishes news itself.

Assessing the damage: Did 2,000, 3,000, or 7,000 hectares burn in Askania-Nova?

A post on the reserve’s Facebook page reported that the fire of 1 September was already the seventh to have broken out in Askania-Nova since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Yet prior to this, some media published reports that 7,000 hectares of land had been burned — this disinformation was spread by the press service of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine.

In fact, during the occupation period, over 3,500 hectares of the reserve have been destroyed by fires – more than a tenth of the entire reserve. This figure was first announced by the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, subsequently confirmed by the reserve itself, and then repeated by Viktor Shapoval in a personal conversation.

Most of the burned areas — 2,208.62 hectares — are protected land that is home to plant formations listed in the Green Book of Ukraine (similar to the Red Book, but containing data on vegetation formations rather than specific plant species).

As reserve staff note, fires in the buffer zone and in anthropogenic landscape areas broke out in agrocenoses – weedy fallow areas and crop stubble. All of the fires within the protected zone occurred in the steppe biotopes that are Askania-Nova’s main natural asset and a model example of fescue and feathergrass steppes in the Black Sea region.

Areas under protection for over a century have been damaged as a result of the fires, including the “Stara” area, protected since 1898, and “Uspenovka,” protected since 1927. In addition, this entire territory is part of the Emerald Network in Ukraine and has a UNESCO certificate under the Man and the Biosphere Program.

Velykyy Chapel’s’kyi Pid may lose its unique biodiversity

The destruction of the Velykyi Chapel’s’kyy Pid by fire was a disaster of equal proportion. This area, which is periodically filled with meltwater in the spring, has the highest diversity of flowering plants in the reserve. The area is so valuable that it has been listed as a wetland of international importance and is protected by the Ramsar Convention, and its biotopes are included in a resolution of the Bern Convention as being of particular value and subject to protection.

“Given the dates of the last large-scale fires (at the end of the growing season), most annual plants had already completed their growing season, a significant portion of the perennials, including rare ephemerals (Gesner, Scythian tulips), were already in a semi-dormant state. In addition, dominant species of feathergrass, listed in the Red Book of Ukraine, were not destroyed, losing only their above-ground parts,” said a representative for Askania-Nova.

Askania-Nova has bigger problems than disappearing plants

According to Viktor Shapoval, fires in Velykyi Chapel’s’kyi Pid pose a greater risk to ungulates than the problem of burning vegetation. This is because the area holds a collection of animals that have been assigned the status of National Treasure in Ukraine:

“The territory is fenced, and if it burns completely, the animals will not be able to get out and seek shelter in a safe area,” says Shapoval.

Large fires also affect the entomofauna (insect species), which, unlike birds or mammals, are unable to avoid dangerous areas. It is this faunal group that suffers the most.

Fortifications, trenches, explosion craters, and other military actions inflict great harm, disturbing the soil cover and creating war (i.e. created as a result of military activity) landscapes.

“This is something that truly destroys the steppe. If not forever, then for decades,” says Shapoval.

Can the reserve recover?

“In fact, for a steppe ecosystem, a fire is not a disaster unless the entire area burns out,” says Shapoval. According to him, fires are a natural phenomenon that occurs relatively often in steppes. They can be caused by lightning strikes, and the steppe ecosystem is generally adapted to fire. During a fire, only the above-ground part of plants is damaged, and perennial species can grow back from their below-ground organs. Secondly, a seed bank remains in the soil, allowing plants to continue existing in the burned area.

Special efforts to restore vegetation are therefore unnecessary when favorable conditions arise.

“On the whole, recovery will be spontaneous. In fact, even in the pre-occupation period, Askania experienced many fires, and vegetation had the opportunity to recover,” said Shapoval.

It is impossible to name a precise timeline for recovery at this stage — it all depends on many factors and their interactions, but in any case, the plant life will recover. Detailed information about the course and dynamics of change will only become available next year, when the growing season comes around again.

However, large-scale fires do threaten protected ecosystems where areas that recover after a fire event may differ in terms of their species composition. A restored Askania-Nova may be strikingly different from the one that has been protected for more than a century.

Main image credit: Rubryka

Comments on “Fires in Askania-Nova: Consequences of military occupation of a reserve”