Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Hrihory Kolomitsev and Viktor Parkhomenko

Forest fires are one of the most tangible and long-lasting consequences of military action, both in nature conservation and economic terms. When the Russian army began using “scorched earth” tactics in 2022, the destruction of Ukraine’s forests increased significantly.

Examining the impacts of military action on the environment, fires that occur in the course of warfare are a particularly powerful factor. A side-effect of both combat operations and a deliberate tactic used by the warring sides, once started, fires can spread uncontrollably, both within active combat zones and far beyond their borders (in mined and occupied territories, for example).

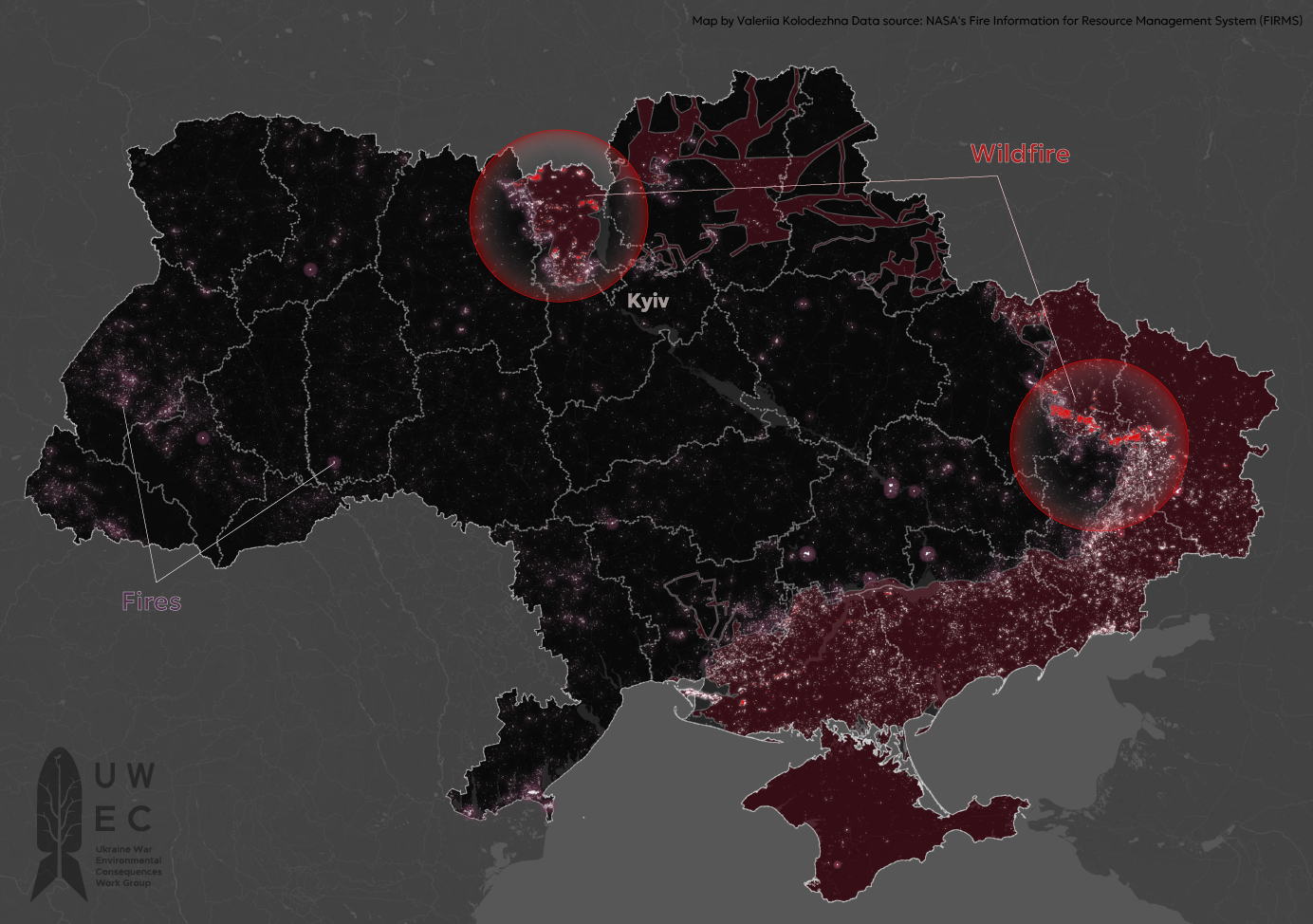

This article presents the results of a recent UWEC investigation into forest fires in Ukraine. In just two years of war, 8,096 square kilometers of Ukrainian territory where fighting has taken place have been affected by fire. Of those, 1,047 sq km is forest that has burned as a result of military action and the inability of Ukrainian emergency services to extinguish them.

Calculation methodology and results

In preparation for this investigation, information was obtained from satellite imaging from Landsat 8 Global Fires I and images from Terra MODIS earth remote sensing (ERS) units. This set of geodata includes information about 131,498 fires recorded by NASA satellites within Ukrainian borders in the period 22 February 2022 to 22 February 2024 – that is, over the first two years of the full-scale invasion.

Data is updated four times a day on average: the orbit paths of the two satellites mean that each passes over the same territory twice daily. They use automatic fire detection algorithms that pick up the powerful infrared spectrum radiation emitted by conflagrations.

On the basis of this data, the satellites record powerful fires that burn for extended periods of time. Despite the possibility of fires spreading rapidly, for instance, in steppe landscape or in floodplains when they can occur between satellite overflights, the majority of fires last long enough to appear on their sensors.

In general, a fire lasts a relatively long period of time, with sufficient persistence to be recorded by means of ERS. So, while undoubtedly genuine, the data obtained by the authors is unquestionably incomplete and the real area of burned biotopes (ecosystems) is significantly bigger. As demonstrated in this investigation, the results of modeling show the locations of fires fairly well, allowing affected conservation zones and valuable biotopes to be identified. Geospatial modeling technologies were used to determine the extent of burned areas. The resulting data has a small error margin, but permits evaluation of the scale to which natural areas suffer from burning.

Too much talk, too little data

A substantial number of publications devoted to the impact of the war on Ukraine’s forests since Russia’s full-scale invasion already exist in both the Ukrainian and international press. Ukrainian politicians also regularly speak out on the subject (estimates of the loss of three million hectares of forest have been voiced several times). Scientific publications with the first estimates of losses are now being published, authored by both Ukrainian scientists and specialists from other countries. Ukrainian societal interest in the topic of forest fires has generated a great number of articles, reposts and comments, especially in the wake of public statements by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, as well as senior figures in the forestry industry.

Scientific publications are far more restrained in their estimates of the scale of such losses, but their data also differs significantly. This happens not only because of a lack of accurate data, but also because authors approach the concept of “loss” or “damage” differently, from the land mines that have made forests off-limits for economic activity to the presence of military operations in an area and complete incineration of forest areas as a result of crown fires. Unfortunately, in the majority of published cases, the studies are not accompanied by an explanation of the precise nature of the damage. Only two very detailed studies are known to exist, both of which should be seen as extremely reliable – these were carried out by staff of the Biloberezhia Sviatoslava Research and Production Enterprise for the Kinburn Spit and by specialists from the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group for the Chernobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. These two local studies show truly enormous areas of burned land.

As for other forest territories in Ukraine, although they have suffered badly from fires, it is hard to provide accurate data, since they are inaccessible for field research due to being mined or in close proximity to active combat zones. It is therefore impossible to carry out precise mapping of burned areas, including, for example, ground fires, which can last for an entire season but can usually only be seen from a satellite or in aerial photographs in the first months. Consequently, evaluation is currently only possible using remote methods. When planning their research methodology, the authors relied on the above two cases of precision mapping as a source of verification.

Why ‘military’ fires have such a powerful impact on nature

Fire is one of the most destructive consequences of war, especially in natural areas, it leads to the destruction of all living beings, including significant losses of soil fauna. Depending on the type of biotopes and time of year, fires also have a wide spectrum of effects on flora: from the insignificant – in the case of winter fires in the steppe – to the catastrophic, i.e. in the forest. In the latter case, this impact also leads to the loss of forest biotope for an extended period. Grassy biotopes, however, take just months to recover. Therefore, assessing the impact of burning becomes more meaningful if it is considered in the context of a separate type of biotope. For example, fires in anthropogenic biotopes (say, on arable land) have no real substantial impact on biodiversity or on whether this particular biotope will recover after the fire, since this depends exclusively on whether the farmers will sow that particular land in the following year.

Weather conditions, soil moisture levels, and the length of time since plant residues were last removed from the area are also a factor in the spread of fires. Thus, in pastures and hayfields, where excess biomass is constantly removed, or in areas where fires are common, this effect will be insignificant. However, in forests or in other biotopes where a large amount of dry vegetation has accumulated, long-lasting fires will destroy roots, grass seeds, bulbs and corms in the soil, along with the animals that live in them.

Forest fires mean devastation

Forests are perhaps the only type of natural ecosystem in Ukraine in which several separate government bodies are responsible for fire prevention and firefighting: the State Emergency Service, forestry enterprises, and local municipalities. Each has its own particular obligations and resources, and they all work unstintingly to prevent forest fires. Of course, forests have this special status due to their social and economic significance, as well as the fact that in the steppe zone forest fires are usually fatal for the forest involved.

In terms of their cumulative effect, the impact of military factors on biotopes make the consequences of blazes in natural areas far worse than if the fires happened in peacetime. For example, the first thing to occur when Russian armed forces invaded the Donbas (both in 2014 and 2022) was that the occupiers seized all accessible administrative institutions, resulting in government work coming to a standstill.

Occupation of Ukraine’s eastern regions in 2014 not only saw the seizure of premises belonging to Ukrainian state entities, but also their property. All firefighting equipment located in the occupied territories was confiscated and subsequently used against Ukraine for military purposes. Even at that early stage of the war, it became clear that of all the various negative factors on ecosystems caused by military operations, forest fires had a particularly virulent impact.

Under normal conditions – that is, in peacetime – fires in forests would quickly be extinguished by units of the State Emergency Service and forestry workers. There are numerous methods for preventing and extinguishing forest fires.

But when faced with ongoing active hostilities, or even afterwards, when an area has been mined and fire equipment has been stolen, it is impossible to organize firefighting operations.

Explosions of military equipment and munitions, as well as incendiary ammunition used by Russian troops, also contribute to fires.

The situation is aggravated by the peculiarities of the forest ecosystems that are typical of Ukraine’s steppe zone. This region contains a wide range of steppe biotopes, floodplains, and ravine forests that are dominated by mixed tree species (in all cases broadleaf forests), as well as “chalk forests”, a biotope eligible for protection under the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. In occupied areas, the sandy soils of the Siverskyi Donets river valley and other parts of the region are dominated by pine plantations. Just a few such forests consist of deciduous trees, mainly invasive alien species such as Robinia pseudoacacia, or black locust.

In fact, pine forests in the steppe zone are the most fire-prone category of forests in Ukraine: they ignite the most easily, and once alight, these fires are particularly destructive. If not extinguished promptly, they will spread freely through the forest in the leeward direction until they run out of trees to burn or are halted by water barriers or rainfall.

As for plantation pine forests, they are not only especially vulnerable to fire, but also quickly break down, even if only partially damaged. The superficial root system of pine requires good soil moisture, so any loss of forest integrity exposes the soil to direct sunlight and rapidly decreased moisture. Insufficient moisture causes pines to weaken and dry out, making the damaged forest even more vulnerable to fire as a result. The main tracts of forest within the combat zone are artificial plantings on the site of post-glacial sand terraces, they are left exposed after burning and become vulnerable to erosion.

It is important to note that steppe zones are characterized by a continental climate, with hot dry summers and cold winters. Under current conditions, the creation of new forests in this zone is extremely complicated: young saplings do not take root well, and more than half of them die within the first year after planting. This means that today it is almost impossible to plant new forests in the steppe zone. Consequently, the loss of plantation pine forests in this region due to fire almost guarantees that it will be impossible to restore these forests in the future.

Historically, forest planting in the steppe zone was carried out to create areas with a favorable microclimate for human life. Today, most forests that surround settlements were created in the past with the aim of creating a climate that was more humid and cooler than the natural one in the steppe zone. The loss of forests thus inevitably causes a deterioration in living conditions for local populations, whose residents, thanks to these forests, have enjoyed a continuous supply of moisture, coolness and decreased wind intensity for several generations.

At the same time, the studied area features natural broadleaf ravine forests (in the steppe zone, such forests occupy deep ravines and gorges, forming a relatively humid microclimate beneath a canopy that allows the growth of full-fledged mature trees) – the “cells” of the region’s forest biodiversity. When creating artificial forest plantations, forestry enterprises often situated them next to natural ravine forests, in order to use the natural moisture and shade of the existing forests for the young artificial forest plantations. The result is that today natural forests and artificial pine forests often form stretches of continuous woodland. Fires that spread easily in artificial pine plantations also lead to the destruction of natural broadleaf forests.

Damage to forest plantations entails considerable economic damage for the region, while the destruction of natural ravine forests has a significant impact on the region’s biodiversity: forest species distributed across Ukraine’s eastern regions are found in relatively small areas.

A good example is the forests of the Siverskyi Donets river valley, where the largest groups of Ukraine’s diurnal birds of prey gather. Most birds of prey are protected both at national level as well as part of Ukraine’s implementation of international agreements. However, today the majority of these birds have moved away to other parts of Europe from the Siverskyi Donets valley, now an active combat zone where fires are common.

Forest fires and radiation

In February 2022, as has been well-documented, one of the main vectors of attack for Russian troops invading Ukraine was an assault on Kyiv from Belarus via the exclusion zone of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Many reports have since been published about the radiation threats caused by the invasion and Russian troops taking up positions on radiation-contaminated land. These events were also accompanied by fires in the forests, which by then were impossible to put out. It is important to note here that even in the pre-war years the absence of roads throughout most of the exclusion zone did not allow fires to be extinguished here. As a result, Russia’s brief occupation of this area cost Ukraine 22,000 hectares of burned forest.

Products of combustion enter the atmosphere in massive volumes as a result of these fires, threatening the effectiveness of the exclusion zone’s barrier function – it was established to prevent radioactive particles from escaping the area again. In other words, it is fires such as these that are now the sole genuinely likely way of radiation being carried beyond the exclusion zone and over large distances.

Studying the fires in Ukraine’s forests caused by the war

The authors first began their research into the consequences of fires resulting from military action back in 2014, when Russian troops seized part of the Donbas. In the period from 2014-2021, although military activities were on a significantly smaller scale than the invasion of 2022, it was natural ecosystems that were affected to a large degree, rather than infrastructure and settlements. Following the full-scale invasion, Russian troops focused increasingly on the deliberate destruction of settlements, employing “scorched-earth” tactics in an attempt to gain ground. For this reason, the losses of natural ecosystems in Eastern Ukraine were possibly even greater during the first phase of the war, starting in 2014, than now, when there is a full-scale war – at least in percentage terms.

It was during this period that some of Ukraine’s particularly valuable nature reserves suffered damage for the first time in many decades, or in some cases for an even longer period. For example, for the first time since the 1920s forest fires occurred in parts of the Sviati Hory National Park, including the Mayatska Dacha and Hora Artema (both protected since 1927), as well as in both the strictly protected (since 1926) Melova Flora and Khomutovsky Steppe areas of Ukrainian Steppe Nature Reserve.

The fact that these fires have occurred in itself represents lost conservation value, for the sake of which these conservation areas have been protected from the least negative human impact for so long, as remaining shining examples of wilderness.

Another case occurred in Luhansk Oblast back in 2014-2017 when the Provallia Steppe area in Luhansk Nature Reserve was almost completely burned, and its central sector, located in the floodplain of the Siverskyi Donets River, was almost completely engulfed by fire. Until then the territories listed above had never suffered.

In other regions of Ukraine, where the war arrived only in 2022, the situation was similar: powerful fires damaged Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve, and all national parks in southern Ukraine. In Dzharylgatskyi National Park, for instance, almost the entire land-based section of this reserve was consumed by fire in 2023.

It is important to underscore that absolutely every single one of the most important protected areas within the conflict zone have been damaged by fire.

Unfortunately, from 2022 onward, the amount of Ukrainian territory affected by the war expanded significantly, and later – as a result of the war’s transition to positional warfare and the use by Russian forces of “scorched-earth” tactics – the intensity of shelling per unit area during combat significantly increased the loss of natural ecosystems from fires.

According to DeepStateUA data, as of the start of March 2024, 7.2% of Ukraine’s total territory has been liberated, while 18% remains occupied. The statistical information on the areas damaged by fire presented in this article applies only to these parts of Ukraine.

In 10 years of war, Russia has carried out actions in Ukraine that closely match the concept of ‘ecocide’, and this can be seen most clearly in the case of forest fires. The fires studied by the authors represent just one of many aspects of the war’s consequences for Ukraine’s nature.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image: Concentration of wildfires in Ukraine during the russian invasion. Infographic by Valeria Kolodezhna