Inha Pavlyi

Ukraine has reorganized its ministerial structure, merging its environmental, economic and agricultural ministries into a single body. Will the move result in more effective environmental governance or a worsening of the situation or hamstring Ukraine’s green policy? And how have Ukrainian environmental organizations reacted to the reshuffle?

On July 21, 2025 the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine abolished the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Mindovkillya) by merging it with two others— the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and the Ministry of Economy. The property, rights and obligations of the liquidated ministries now come under the auspices of the newly formed Ministry of Economy, Environment and Agriculture of Ukraine.

In itself this move is not unusual. Ukraine has reorganized the environmental ministry (the successor of a Soviet-era predecessor) several times since its creation in 1991, including ill-fated mergers with other ministries. And in the European Union (EU) there are also examples of environmental ministries being combined with other executive bodies. This is the situation in Croatia, France, Ireland, Latvia and Spain, among others. However, the environmental component of combined ministries like these remains a priority and is not subordinated to other concerns, as the Ukrainian environmental law organization Environment People Law noted in its public statement on the critical consequences of the closure of Mindovkillya. To put things in perspective, Hungary is the only EU country where environmental protection is linked to agriculture within a single ministry—with a clear priority in favor of the latter.

At the end of July, Ukraine’s newly appointed Minister of Economy, Environment and Agriculture Oleksiy Sobolev held a briefing, in which he explained how the new ministry would work. Its priority environmental areas are defined as irrigation and melioration, increasing agricultural production and attracting investments in green industrialization. In terms of implementation, the focus will be on waste recycling, forest restoration and projects for the development of timber markets, developing the critical minerals and raw materials sector (particularly rare earth metals), conducting environmental impact assessments (EIA) while maintaining a corresponding unified register, and data digitalization.

Sobolev’s deputy Yegor Perelygin will be in charge of policy on subsoil use, natural resources, the collection and digitalization of geological data, and the extraction of critical minerals.

‘Environmental protection functions should be carried out by a separate institution’

In the new ministry, these environment-related areas are now clearly inseparably linked with the economy, says Greenpeace Ukraine’s director Natalia Gozak, who fears this may create problems.

“State environmental protection functions should be performed by a separate institution in the country,” she explains. “The processes involved with studying the impact on the environment, assessing this impact are more complex. Environmental protection is not so much a question of economics as of certain restrictions in the use of natural resources, which should be defended by a separate ministry, which has its own perspective.”

As Gozak points out, the aim of the Ministry of Economy and Agriculture is to support development and maximize the use of natural resources, while the Ministry of Environmental Protection focuses on setting boundaries for this. “And when these two contradictory processes are combined in one, then the priorities change. It is clear that now the ministry’s priority will be the economy,” she warns.

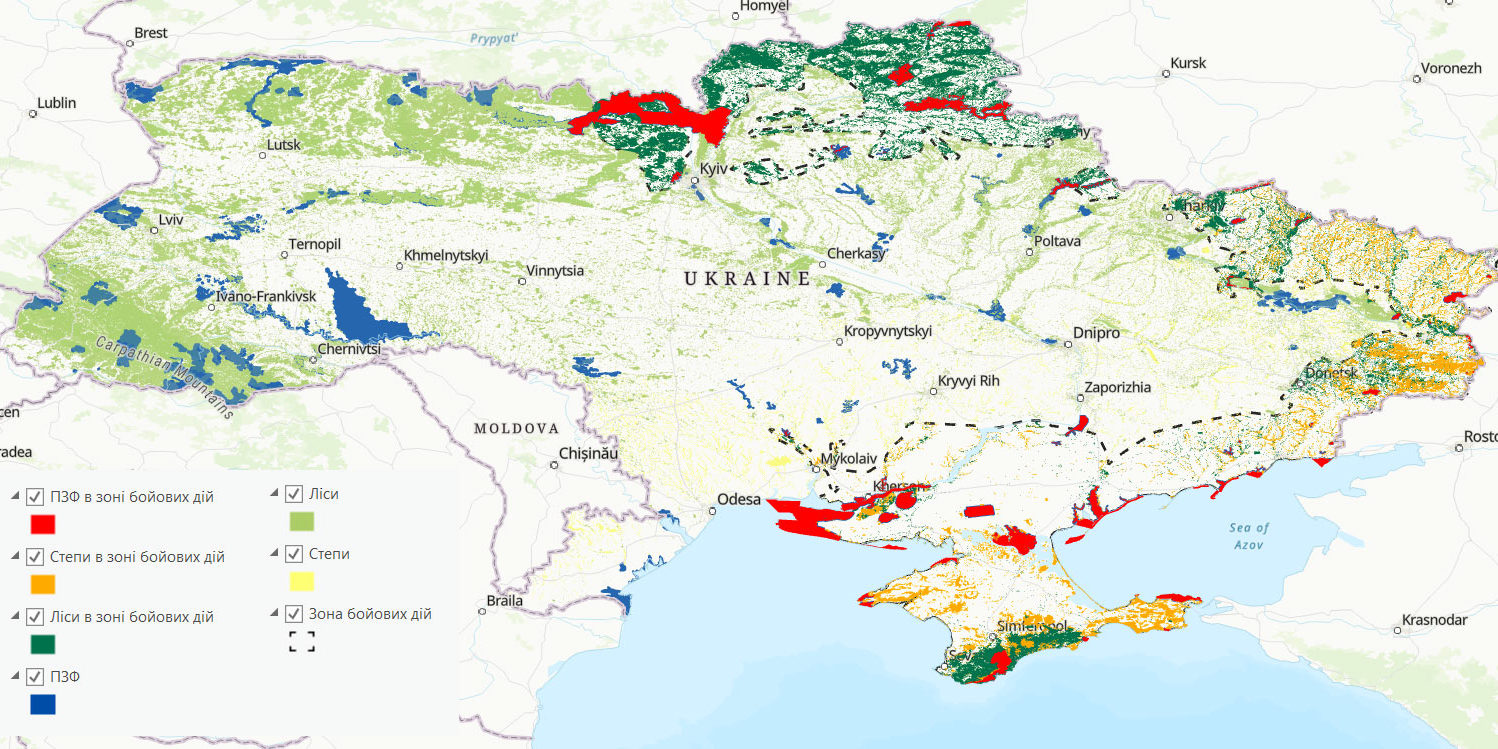

A well-functioning, independent environmental protection authority is of crucial importance for Ukraine in the context of the full-scale war unleashed by Russia. Military action has inflicted catastrophic damage to atmospheric air, land and water resources. The cost of clearing minefields and restoring Ukraine’s destroyed forests, fields and polluted water bodies is currently estimated at more than $120 billion—a price Ukrainians will have to face once hostilities are over. The shuttering of Mindovkillya, which would have coordinated such restoration, can only slow down these processes.

Natalia Gozak thinks that work on calculating losses and recording war crimes against the environment will continue unaffected. “But post-war restoration will definitely receive a lower priority after the liquidation of the ministry,” she says. “If we talk about green restoration in the context of energy, the transport system or construction, then this will continue in one way or another. Again, however, there is a threat of a reduced focus on this important process for Ukraine. Especially in the context of European integration.”

Despite widespread discontent among representatives of environmental organizations, scientists and human rights activists over the dissolution of Mindovkillya, the authorities have yet to provide a public justification of the reasons for this reshuffle and the significant reduction in the attention paid to environmental protection issues by the state.

How will the move affect the implementation of EU environmental reforms?

While Mindovkillya had received a certain amount of criticism, this doesn’t necessarily mean it was doing a bad job, says lawyer Sofia Shutyak, deputy chairperson of the agrarian, land and environmental law committee of the National Association of Ukrainian Agrarians. In her opinion, this merely proves that the Ministry deals with a wide range of issues, and therefore conflicts of interest naturally arise. These are often not public, and while they may be presented as part of the fight for a cleaner environment, in reality they are all about preserving businesses and their income, without due attention to environmental issues.

In February, the Cabinet of Ministers approved the government’s Priority Action Plan for 2025, However, in spite of everything, the plan largely left Mindovkillya on the sidelines.

“The Plan does not contain key tasks for environmental monitoring, which is the key to generating environmental information that should form the basis for decision-making,” explains Sofia Shutyak. However, the plan does not raise the issue of environmental fees paid by companies to offset environmental damage (except for waste disposal fees), which will have an effect in the case of industry being made more accountable, nor does it contain an acknowledgement of the value of natural ecosystems and the damage caused to water, land resources and biodiversity by military action. Other issues were absent, too: Shutyak highlighted the practice of monetizing damage to ecosystems through retrospective fines, as well as the importance of broadening criminal and administrative liability in the environmental sphere.

“The Plan also did not provide for a role for Mindovkillya in the negotiation process to prepare Ukraine for joining the European Union, namely, the harmonization of all regulatory acts with European standards. EU regulations are directly applicable and therefore their introduction through certain changes in regulatory acts is wrong,” she continued.

EU legislation and standards are divided into 35 chapters covering different spheres. These form the basis of the legislative model to be followed for each candidate country and must be considered during accession negotiations. Chapter 27, “Environment and Climate Change,” is one of the most complex in the EU accession process in terms of the funding, institutional capacity and profound habitual changes it requires from individuals and industry alike. This chapter contains more than 200 EU legislative acts.

The criteria for joining the EU can be defined as political (stable institutions that can guarantee democracy, the rule of law, human rights and the protection of minorities), economic (a functioning market economy and the ability to withstand competition in the EU market) and the acquis communautaire, a set of common rights and legal obligations that are binding on all EU member states).

Ukraine has made significant progress in implementing European reforms, as Sofia Shutyak notes. In addition, Ukrainian business, which is EU-oriented, has shown that it is capable of operating according to the rules of the European Union, as the European Commission’s 2024 report makes clear.

Admission to the European Union is contingent on the adoption of a number of directives concerning environmental protection: the Air Quality Directive, the National Emission Reduction Commitments Directive, the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, the Water Framework Directive, the Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive. It is also important to regulate industrial emissions, waste management and the protection of the civilian population.

As Shutyak explains, preparing Ukraine for joining the EU not only requires the adoption of new legislation. “Most of the directives have been integrated into current Ukrainian law, since we have always had high-quality legislation. But regulations and other mandatory EU directives don’t need to be created. They need to be translated [into Ukrainian] and executed. After all, one of the criteria for a country’s readiness is a change in the behavior of all its [administrative, corporate and individual] subjects. The role of Mindovkillya in this process is indispensable, since the economy is just one of the tools for environmental protection, but the environment is a much narrower issue,” she says.

She cautions that the formation of a larger, multi-track ministry will complicate bureaucratic processes and the ministry’s central task as defined in Article 20 of Ukrainian law “On Environmental Protection,” which outlines the competence of the central executive body to implement state policy in the field of environmental protection.

“It wasn’t just that the Ministry was abolished—Ukraine lost an important policy track. The only way forward is to restore Mindovkillya before it’s too late,” says Shutyak.The dissolution of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine amounts to no less than the sidelining of the environmental agenda. For a country that has been trapped in a full-scale war for three and a half years, causing billions in damage to the environment, this is a step back and threatens to hobble environmental reforms on the path to European integration. The environmental community is therefore calling on Ukraine’s leadership to abolish the decision to merge Mindovkillya with other ministries and to strengthen work on environmental protection instead. UWEC Work Group supports this call and will continue to monitor the development of environmental policy in Ukraine.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image source: pb-news.info