by Oleksii Vasyliuk

Translated by Nick Müller & Jennifer Castner

In 2014, Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea led to the peninsula’s militarization. Military drills, often more destructive to nature than direct hostilities, were held near or even within protected areas. At the same time, Crimea’s unique ecosystem is extremely important for biodiversity conservation both in Ukraine and across the entire northern Black Sea region.

Nine years of information gathering and almost a year of collaborating with expert analysts from the NGO Crimea-SOS went into writing this article. Analysis showed that the change in Crimea’s political status and its separation from Ukraine’s unified system of state oversight and administration very quickly led to unprecedented environmental consequences.

In this series of articles, we will examine the impacts of Russian annexation on the peninsula’s environment. The first article will focus on militarization of Crimea. In subsequent articles, we will consider the problems of increasing environmental pollution, natural resource extraction, biodiversity destruction, and the environmental consequences of Russia’s large-scale construction projects in Crimea, such as the Kerch bridge and Tavrida highway.

From a biological point of view, Crimea is a unique region whose flora and fauna have preserved a number of rare and endemic species found only on the peninsula and that are incomparable with the rest of Ukraine. It is not surprising that in this regard, every third nature reserve in Ukraine is found here. The oldest of them, Crimean Nature Reserve, first received special conservation status back in 1919, almost simultaneously with Askania-Nova Reserve, Ukraine’s first and one of its most famous reserves. In 2014, after the Russian Federation’s illegal annexation of Crimea, the situation radically changed.

For Russia, the annexation pursued goals far from tourism, health recreation, protection of its nature reserves, or even the expansion of its national territory. That country’s goals were and remain predominantly militarily focused: to block deployment of Nato’s fleet in Crimea (in the event thatUkraine joins Nato), dominance in the northern Black Sea region, and creation of a powerful military and logistics outpost for which they even launched the “project of the century” – construction of the Kerch bridge.

Less important but nevertheless strategic goals included the blockade of Ukraine’s Azov Sea ports, seizure of its gas fields (one of which Russian troops even seized just off the coast near Odesa and far from Crimea), and the opportunity to present Crimea’s seizure as an incredible illustration of its successful imperial policy. Another goal was co-opting supporters of Russia’s expansion with valuable real estate handouts in Crimea.

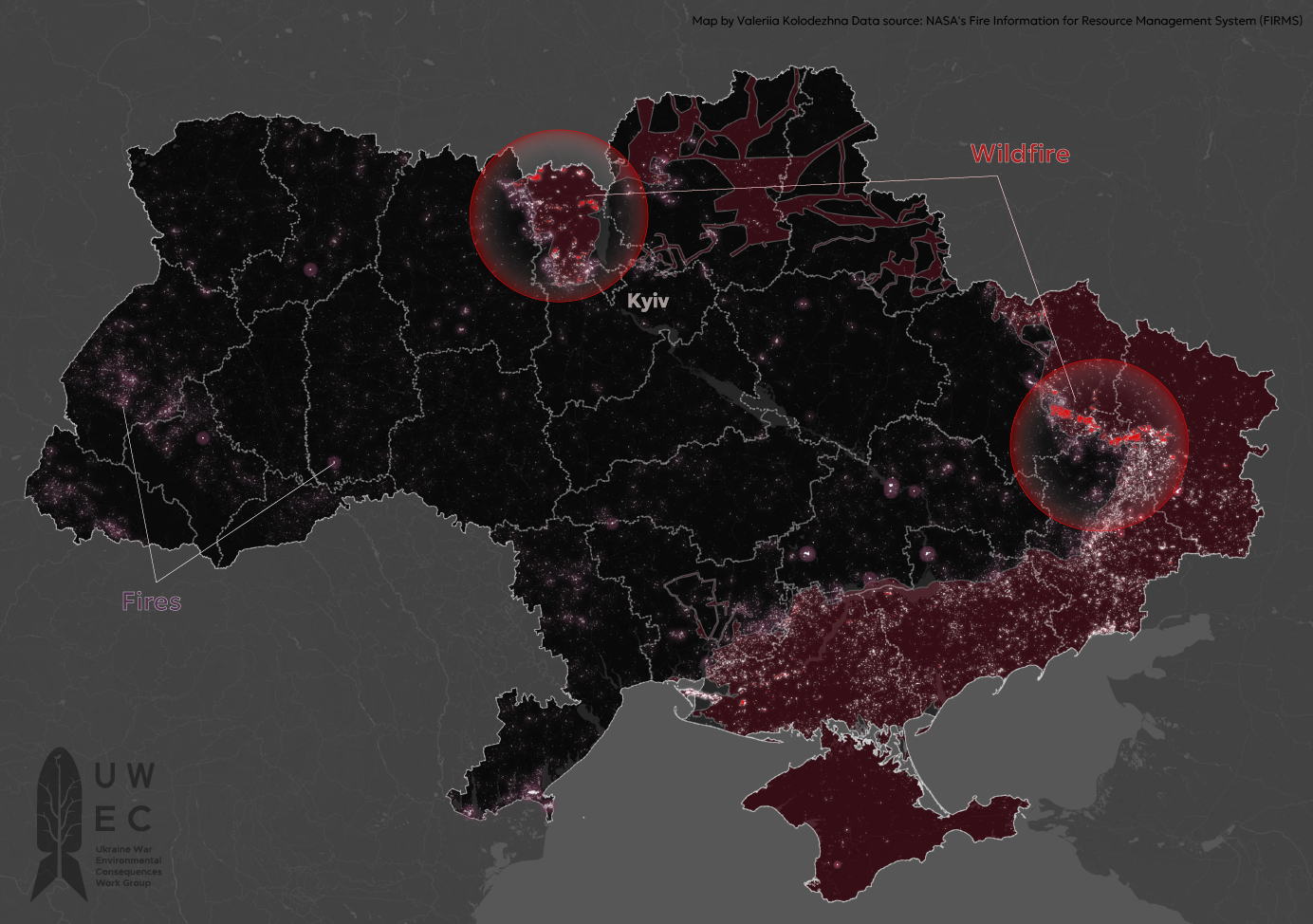

Show full infographic at new tab

Militarization of the peninsula during occupation

Until 2022, Russian military units based in Crimea since 2014 did not directly participate in hostilities against Ukraine. But at the same time, military exercises at various scales occurred almost continuously on the peninsula.

The situation changed starting on the very first day of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Military drills ceased, but Crimea became a springboard for Russian troops. Missile strikes were carried out throughout Ukraine from Crimea and attack helicopters and missile-carrying aircrafts used it as their home base as well.

Conducting military drills requires large natural areas with low population density, free of tourists, and without developed infrastructure. At the same time, military exercises using weaponry and testing of new weapons have had the same negative impact on the environment as actual hostilities.

The most prominent consequences of both the hostilities and military exercises – damage to the landscape and vegetation, chemical contamination of the soil and groundwater – have a cumulative effect. At the same time, repeated exercises further damage landscapes and vegetation and pollute the soil even more. Areas where military exercises take place often suffer more greatly than combat zones when repeatedly bombarded with polluting ordnance.

As a result, there are damaged landscapes, chemically poisoned areas unsuitable for agriculture, and a large amount of unexploded ordnance. Between exercises or after their completion, active training grounds remain inaccessible to the local population and tourists for recreational use. It is clear that only large, uninhabited natural areas and those not in active economic use can become military training grounds.

The size of the areas where Russian troops have set up military training grounds is impressive. It is impossible to determine the boundaries of all sites using open data sources alone. Taken together, Opuk and Chauda training grounds have a total area of more than 55,000 hectares. These areas are natural landscapes (plains suitable for grazing, haymaking, and tourism) and before becoming military grounds, they provided a large number of ecosystem services. At present, any use of these territories by civilians is impossible.

Environmental pollution at military training grounds

Without enough information about the quantity and caliber of the ordnance used, we cannot calculate the damages or otherwise express the extent of environmental damages. However, we can describe the nature of this damage and draw conclusions about the condition changes in the territories now being used for military training grounds.

Munitions explosions of any caliber cause a chemical reaction, which, in turn, pollutes the atmosphere (with those reagents that had time to react) and soil (with the reagents that did not have time to react during the explosion). In the case of munitions explosions in the sea, the vast majority of contaminants end up in seawater, regardless of those proportions. Over years of occupation, the total number of ordnance explosions in some parts of the Kerch Peninsula is so large that craters merge into a single area of damaged soil where it is not possible to count individual craters. For example, Russian media sources have reported that over 500 metric tons of ammunition were used in just five days during the Kavkaz-2016 exercises at Opuk training ground.

Despite the lack of reliable details about the volume of ordnance used during military drills in Crimea, official Russian armed forces sources publish evidence of the regular nature of military exercises conducted on the peninsula. Information about them was often published by the Russian media and was accompanied by photo and video materials that clearly illustrate the scale of military activities on the training grounds.

The largest exercise, Kavkaz-2016, began right after the training grounds received official status as part of the Southern Military District of the Russian Federation (the Opuk training ground is assigned to the 810th Marine Brigade of the Russian Navy, and Cape Chauda is assigned to the air defense forces).

The first drills at Cape Chauda (28 May – 4 June 2016) were accompanied by firing air missiles (Aviadarts-2016 competitions). Video footage of the September exercises not only permits identification of locations, but also enables an understanding of the extent of the destruction.

Here are a few still images from the exercises conducted in September 2016 at Opuk training ground.

Fig. 1 Munitions explosions on Kerch Peninsula and in nearby coastal waters, Emerald Network. Source: Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation YouTube channel.

It is obvious that such activity is compatible neither with the safety of the population, nor with nature protection. Moreover, the lands used for military training have actual nature conservation status. With a small margin of error, we can say that at least the Chauda, Opuk, and Bagerovsky sites on the Kerch Peninsula are fully within the Emerald Network of Europe. Also, the Opuk site includes Opuk Nature Reserve, while the Bagerovskiy training ground includes all of Karalar Regional Landscape Park.

Also, a video of the exercises at Opuk training ground shows (starting at 13:33) that the entire steppe area (much larger than the reserve itself) burned completely during the exercises.

Large areas of steppe have also completely lost their natural vegetation cover as a result of military equipment maneuvers.

The movements of Russian Armed Forces units were also recorded outside military training grounds, including inside Magic Harbor National Park.

It is especially dangerous that targets during Russian Armed Forces drills in Crimea were chosen both within the testing grounds themselves and in the sea, with devastating effects on marine biodiversity.

In addition to the obviously detrimental effect on biodiversity, particularly on planktonic organisms, munitions explosions in sea water lead to chemical contamination. Unlike on land, pollutants freely spread in water bodies and also accumulate in aquatic organisms, including fish. Apart from ammunition fragments and chemical pollution, explosive and sound waves are also hazards.

Apparently, these drills took place almost continuously. Before the 2022 invasion, Russia may have needed to justify the ongoing presence of a significant contingent of military forces on the Crimean Peninsula.

Consequences of military drills on Crimean nature

According to our estimates, the Opuk training ground is roughly 55,000 hectares in size. We measured this area by marking the boundaries of land damaged by military activity on satellite images.

Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to calculate the number of craters from explosions because the specifics of the Kerch peninsula’s ground cover prevent the formation of true craters visible on satellite images, and in some places there are so many craters that, over areas of dozens and sometimes hundreds of hectares, vegetation is almost completely destroyed.

Lands used for military training grounds are some of the last places where rare species of steppe zone birds were found in Ukraine: Demoiselle crane, Great bustard, Eurasian thick-knee, and Collared pratincole. These largely unpopulated areas were in fact the only place in the country where these species could safely nest. In the case of Great bustards, they also form clusters here in the winter months.

It is almost impossible to imagine how these species manage to nest during military exercises (even when they are conducted 5-10 kilometers distant). At the same time, all these species are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine and are protected at the European level by the Berne Convention.

Separately, it is worth mentioning the Little bustard bird species. Once very numerous on Ukraine’s once uninterrupted steppes, this species has almost disappeared as steppe is converted to croplands. Today, 30-50 individuals are found in Ukraine during nesting season (when five to seven females may nest), and in winter the total number reaches approximately 70-80 individuals.

Factors decreasing abundance are the loss of biotopes, destruction of nests during grazing and haymaking, human disturbance, increasing numbers of feral dogs and corvids, removal of clutches and broods, and shooting adult birds. According to the Red Book of Ukraine, the only place in the country where this bird is found is on the Kerch Peninsula. Since the start of military exercises in Crimea, we have not found any evidence confirming the continued presence of this species.

There are other negative consequences of militarization. For example, significant amounts of water are taken from reservoirs and wells, to service new military units and a growing amount of equipment. Local residents have complained repeatedly about water shortages.

International legal mechanisms as potential solutions

In 1977, the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) was adopted. It was the first document containing universally binding rules for the treatment of the environment during international armed conflict.

Article 35 establishes the basic methods and means of warfare, indicating that the right of the conflicting parties to choose the methods or means of warfare is not unlimited. In particular, it is prohibited to use weapons, projectiles, substances, and methods capable of causing excessive injury or excessive suffering. Paragraph 3 of this article also provides for a ban on the use of methods or means of warfare that are intended to cause long-term and serious damage to the natural environment.

In 1982, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 37/7, which approved the World Charter for Nature. In this document, Principle 5 states that “Nature shall be secured against degradation caused by warfare or other hostile activities.” Principle 20 states: “Military actions damaging to nature shall be avoided.”

In 1992, the UN General Assembly adopted the resolution “Protection of the environment in times of armed conflict”. The resolution pointed to the violation of international law in the form of environmental damage and depletion of natural resources not justified by military necessity.

Since there can be no possible intention to harm nature during military exercises, we can state that the Russian Federation, by its actions in Crimea, has repeatedly violated the above provisions of international treaties.

In 2016, the UN adopted a document on the need to protect the environment of Crimea from the consequences of militarization. On 27 May 2016, the UN Environment Assembly adopted a UNEP resolution “Protection of the environment in areas affected by armed conflict,” which recognizes the role of healthy ecosystems and areas with sustainable management of natural resources in reducing the risk of armed conflict. However, there was no reaction to it – three months later, the first high-powered Kavkaz-2016 training exercises took place in Crimea.

On 17 December 2018, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on “The problem of militarization of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the city of Sevastopol, Crimea, as well as parts of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.” It was supported by 66 countries, opposed by 19, and 72 countries abstained. The resolution directly noted that Russia’s actions to militarize Crimea pose an environmental threat not only to its environment, but also to all countries of the Black Sea basin, and can “undermine regional security and entail significant negative environmental consequences in the region.”

In 2019 and 2020, the General Assembly again adopted similar resolutions, which once again drew attention to the environmental consequences of Russian military exercises in occupied Crimea.

However, as demonstrated in this article, many of the largest maneuvers occurred after the adoption of resolutions by the UN General Assembly.

Militarization of the Crimean peninsula has had an obvious destructive effect on the environment during the nine years since annexation. Military use of Crimea was and remains the primary goal of its annexation by Russia.

We can assume that the consequences of Russia’s militarization of the peninsula will have an effect on the environment almost on par with the consequences of military action. Pollution of Crimea and the remains of ordnance at military ranges will temporarily worsen the state of biodiversity. At the same time, these consequences will lead to a decrease in the number of people visiting many areas and, in general, to the long-term loss of Crimea’s recreational status. Temporary destruction can become long-term, and it may not be possible for nature to be restored.

Main image source: YouTube

Comments on “Nine years after Crimea’s annexation: militarization’s environmental consequences”