by Anton Lementuev

Translated by Nick Müller

In 2022, the European Union’s fifth sanctions package banned the purchase of coal from Russia. Experts widely believed that the resulting logistical and financial difficulties facing Russian coal miners would seriously impact the industry. However, this did not happen, and protest activity in Russia’s main coal-mining region, Kuzbass – responsible for 60% of all production in Russia and half of its national exports – did not falter.

Given the secrecy of imports/exports and sectoral statistics, it is difficult to make accurate forecasts about the coal regions. In the absence of human rights protection and information support, increased pressure on dissenters can halt protests and further harm living conditions despite discontent among the population.

February: First sanctions and forecasts for the coal industry

On 24 February 2022, the full-scale invasion of the Russian army into Ukraine began. To many experts it seemed, at first, that the days of the coal industry in Kuzbass, Russia’s main coal-mining region, were numbered: Russia does not produce the necessary components to maintain mining equipment, nor do they produce heavy mining equipment. International sanctions could end access to bank financing, and coal commodity markets could close. Without maintenance, mining combines could remain underground and coal conveyors could remain at the surface, with excavators and drilling rigs frozen at the bottom of large and small open pits. Many thousands of service companies serving coal miners could also be left without payment or spare parts. Tens of thousands of people may be left without livelihoods in company coal-towns in Kuzbass, including Kiselevsk, Prokopyevsk, Kaltan, and Belovo.

By the end of 2022, economists carefully and at length claimed that the coal industry had come to an end. In contrast, from that spring to today, Kuzbass industry officials have been optimistic again and again, despite the fact that in summer 2022 coal industry Minister Oleg Tokarev spoke about the critical situation surrounding coal exports. Even in pre-war times, it was typical for Kuzbass to simultaneously sound the alarm and discuss the coal region’s future – as was the case in January 2022, 2020, 2013, and earlier. The reason for optimism is based on the idea that both Europe and Asia would still need coal, and Russian coal companies would find a way out of this situation if they could expand throughput capacities on the Baikal-Amur Mainline and Trans-Siberian Railway(s).

Spring: Subsequent sanctions and complications

In March, it became publicly known that equipment manufacturers, suppliers of engines (Cummings, Caterpillar) and spare parts began to leave the Russian market. Shipping operator Maersk left, affecting well-established supply chains of everything necessary to ensure smooth operation of the mining and service industries. In October, Russian Railways officially admitted there was a shortage of imported bearings.

Thanks to a mid-March 2022 decision by the Russian government, coal miners lost one of the most important tools they had for maintaining export volumes: the rule of non-discriminatory access (NDA) to coal transportation by rail. NDA gave a higher priority to the export of coal from Kuzbass, Khakassia, Buryatia, and Tuva, and without this priority, Russian Railways could reject coal for more profitable cargo (oil, oil products, metal, containers). Instead, a temporary rule was created, causing tremendous controversy and confusion, and its use was extended until summer 2023.

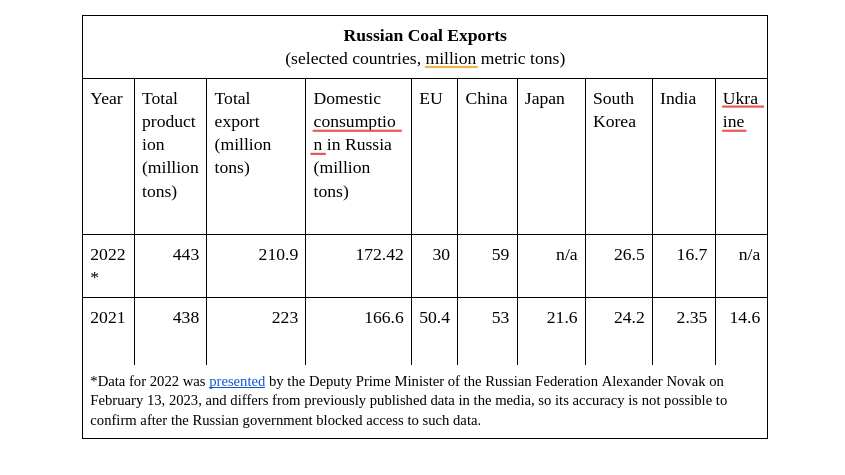

In April, news of the upcoming coal embargo broke: EU countries would stop buying coal from Russia as early as August 2022. Japan announced an embargo at the same time. China, India, and South Korea did not impose bans, and although the latter promised to abandon Russian coal, it actually increased its purchases of coal as shown in Table 1.

European energy sector ambiguity

Before its embargo on coal, the European Union consumed a significant share of Russian and, in particular, Kuzbass exports. In 2021 alone, the European Union purchased approximately 30 million tons of Kuzbass coal. The European coal market has been considered a premium market for Russia with a short haul (distance) and low competition. For comparison, in October 2022, the cost of thermal coal in northwestern Europe was $300 per metric ton, and in China – $130. And, despite unprecedented discounts on Russian coal from the moment the embargo was announced to its implementation, coal exporters, having sold 30 million tons to the European Union, earned four times more money than a year earlier for the same volumes and during the same period. Thus, not only did Russian coal miners get rich on pre-sanctions hype, but so did European energy companies that profited from increased tariffs, as well as the entire supply chain.

In addition, in December it became known that European insurers of ships transporting coal to countries in the Asia-Pacific region had reaped large profits after the embargo (since autumn 2022) on the export of Russian coal. It has not yet been possible to verify the accuracy of the information, but it would be worthwhile: Bloomberg published such information at least once, citing dubious anonymous sources.

The fact that the sanctions were eased can be indirectly proven by the growth of coal exports to China and South Korea, including through remote ports in European Russia – Ust-Luga, Vysotsk, Murmansk, and Taman due to the low cost of freight, which also depends on the behavior of those insurers mentioned in the Bloomberg article. If these facts are confirmed, then this is a fairly important point to investigate in terms of the sanctions’ effectiveness and methods for their circumvention.

Did Kuzbass survive?

The main coal-producing region of Russia (60% of all production and half of exports), Kuzbass experiences the sanctions slightly more negatively than the industry as a whole. In 2021, Kuzbass produced 243 million tons, in 2022 – 223.6 million tons. Today, there is neither a massive delay in distribution of wages in the industry (on the contrary, we can talk about growth in numerical terms), nor is the labor market very competitive. In 2022, the number of vacancies in Kuzbass coal companies increased by 43%. Executives and entrepreneurs close to Kuzbass coal companies expressed disappointment in forecasts by economic experts whom they had previously listened to and adjusted their plans accordingly.

The problem associated with the departure of Caterpillar and Cummings has been somewhat resolved. This is presumably due to the existence of parallel imports, new production of a number of spare parts within Russia, and making equipment substitutions. Entrepreneurs working in the coal service sector had previously found ways to solve very complex logistical and financial problems. They are accustomed to playing by ever-evolving rules in the face of tax pressure, corruption, kickbacks, and the low level of justice found in “electoral sultanates” (subjects of the Russian Federation that always vote overwhelmingly for the ruling party), including Kuzbass.

At the same time, the population outflow from Kuzbass continues. The region is a loss leader for this indicator in Russia. Life expectancy is decreasing: according to statistics from Kemerovostat, Rosstat, and annual state reports on the health and epidemiological well-being of the population, residents of Kuzbass fall sick more often and die at a younger age than the average Russian.

A recent study showed that risks for congenital malformations in babies are also disproportionately high in Kuzbass cities where coal mining is the most intensive. Among the cities studied, residents of Kizelevsk, where coal is the only industrial activity, face the greatest risks of birth defects. The risks in Kiselevsk turned out to be even higher than in Novokuznetsk, where three metallurgical plants operate.

Optimism with consequences

In the last years before the start of the war, the first talks began in the region about the need to diversify the Kuzbass economy and the importance of moving away from an economic model based solely on the coal industry. Prospects for growth in coal exports to Asian-Pacific countries and the friendly optimism of Russian officials on this issue seem to destroy hopes for its economic diversification.

Against a backdrop of war, sanctions, and increasing dependence on coal exports, anthropogenic pressure on nature will grow in the region, as will the number of violations of the rights of citizens to live in a healthy environment, as guaranteed by Article 42 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation. Environmentalists propose that if Kuzbass officials want to stem the flow of out-migration and increase life expectancy in the region, they must use the current (sanctions) situation to quickly abandon coal dependence.

Together with international colleagues, Ecodefense, a Russian environmental group, has been trying to persuade the West and energy companies for years that continuing to buy irresponsibly-mined Russian coal is immoral in terms of the both value of the human life and the severe environmental and climatic consequences for the entire planet.

Uncontrolled methane emissions from open-pit coal mines and degassing mine installations, countless endogenous fires within tailings dumps, (growing each year in Kuzbass alone by about three billion tons) all increase climate risks. The way out of this situation could have been a dialogue between the Russian government, coal companies, scientific community, and the economic bloc, followed by the development of a fair program for transitioning to alternative economic activities to eliminate coal mining’s negative consequences.

With one hand, in launching the “special military operation” on 24 February 2022, President Putin tragically solved the problem of the EU’s immoral coal imports for hundreds of thousands of people, while the other hand eliminated the hope of a just transformation of the Kuzbass economy, a process that is unthinkable without Western technologies, experience, and investment. It is unlikely that residents of the Kuzbass will see the return of clean rivers, white snow, and longer life in the foreseeable future.

2023 will show whether the Russian coal industry will continue to develop or stagnate; in January production in Kuzbass had already decreased by 7.9%

Protests in Kuzbass: What has changed?

Increases in coal mining in Kuzbass are inextricably linked with the growth of protest activity among local residents. The most prominent and earliest case was a protest by residents of the towns of Alekseevka, Ananyino, and the village of Apanas in Novokuznetsk region in 2010-2013 against a coal mine that had begun to operate nearby.

In 2017, Novokuznetsk hosted the first mass rally in Kuzbass history against coal mines. In June 2020, a tent camp sprang up to protest plans of Kuznetsky Yuzhny Mine LLC to build a coal loading station. This was an extremely dirty coal mining infrastructure facility near the village of Cheremza (near Myski). In the summer and late autumn of 2022, residents of the town of Apanas and the villages of Alekseevka and Ananyino blocked attempts to recommence mining operations at the open pit, where mining had last occurred in 2013. These are just a few examples of a huge number of various protests against the actions of coal companies operating in the region.

All types of protest activity are completely banned in Kuzbass, including solo pickets since the beginning of the pandemic. Despite this, protests still happened, as, for example, in Cheremza in 2020, where people were subsequently fined. In addition, sometimes “punitive” searches took place in their homes. 2022 was no exception; searches in Alekseevka were conducted that fall.

Over the past 10 years, not a single human rights organization has had an ongoing program in Kuzbass beyond a few individual cases. The only high-profile and successful court campaign known to the author opposed plans by StroyPozhService LLC to build a coal mine near Mencherep in Belovsky District. This case was litigated by lawyers from Team 29, a now liquidated human rights organization from St. Petersburg, with the support of Ecodefense In 2018-2019. At the time, a local court ruled in favor of several hundred local residents, and the planned seizure of land from them in favor of coal miners for “state needs” was challenged. However, in the overwhelming majority of such cases, activists were always forced to find legal protection on their own.

In 2022, the number of environmentally hazardous projects did not decrease. For example, a year earlier, plans for the construction of the Krapivinsky hydropower plant (HPP) on the Tom River were updated and continued to be implemented in 2022. The HPP’s reservoir would inundate high conservation value natural areas and collect industrial and municipal wastewater from the south of the region. A decision about the HPP’s construction was issued by the Ministry of Economic Development and the region’s leadership as a means of reducing dependence on coal. However, at the same time, local authorities spoke about plans to establish new coal enterprises or expand existing ones near Alekseevka, Talzhino, Gavrilovka and others.

Despite the wartime situation, there were incidents of one sort or another that indicated community concerns about the behavior of local authorities or specific companies in Kuzbass. In a remarkable incident in January 2023, residents near Cheremza recorded a video message in German to protesters opposing energy company RWE’s plans to mine coal in Lützerath – a far-away community in the Siberian hinterland expressing solidarity with German climate activists.

Experience has shown that, both before the start of the war and after, non-violent forms of direct action are the most effective way to protect the rights of citizens to a healthy environment in Kuzbass. Local residents learned to come together and support one another in the face of pressure and repression, regardless of whether they were in different cities or even regions. This happened during a protest camp in Cheremza in 2020, a court campaign in Mencherep in 2018-2019, a series of protests in Kiselevsk in 2019, and also during a confrontation with coal miners in neighboring Khakassia in 2018-2022.

For the most part, citizens have learned to work effectively with the media and to organize, when possible, a defense team in court and during interrogations, despite not having external funding sources. In January 2023, for example, local activists successfully persuaded a judge to invalidate the results of the environmental impact assessment report for the Krapivinsky HPP project, while earlier (February 2022) the police blocked entry for the project’s opponents at the hearings. In another case in late autumn 2022, residents of Apanas, Alekseevka, and Ananyino kept watch around the clock despite freezing temperatures on key roads, blocking attempts to mine coal at Apanasovsky Mine.

Consequences of a year of war for the coal industry in Russia and the Kuzbass

In 2022, China and India were the main drivers of coal exports from Russia. This was especially noticeable during a ban on coal imports to China from Australia. However, no one can guarantee that the Chinese government won’t switch to buying mainly Australian coal again tomorrow, to the detriment of Russian coal supplies.

Environmental protests and activist campaigns have continued in the region. Unfortunately, however, they receive much less media attention than previously now that independent media are largely blocked inside the Russian Federation, with many editorial offices and journalists forced to leave the country. In addition, critical independent media focus most of their resources on covering the war and neglect current events outside of the capital. Unfortunately, today Kuzbass activists are completely unable to obtain legal support from human rights organizations.

Anton Lementuev is regional coordinator of the Russian environmental group Ecodefense in the Kuzbass region in southwestern Siberia, Russia.

Main image source: Ecodefense

Comment on “Siberian coal through the lens of war”