Oleksiy Vasyliuk and Viktoria Hubareva

The self-proclaimed government of occupied Crimea is cynically lopping off chunks of the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve in order to build lucrative residential and tourist infrastructure.

Russian military aggression against Ukraine dates back to 2014, when Moscow annexed the Crimean Peninsula and subsequently fomented an armed conflict in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Russia’s actions against Ukraine are a crude violation of the UN Charter and a number of principles established in international law: in particular, the non-use of force and the threat of force, the inviolability of state borders and the territorial integrity of states, and the fulfillment of international obligations.

Under Russian occupation, the protected status of several territories belonging to Crimea’s nature reserve fund (NRF) has either been annulled or downgraded through decisions by the occupying authorities. This has presented an opportunity to utilize protected land for projects that are at odds with the conservation of nature, with some areas already having been cleared of vegetation. In addition, the nature reserves have been subordinated to the so-called Republican Forestry Management Committee”, as a result of which scientific work has ceased to be a guiding principle in the operation of Ukraine’s reserves.

Under the new legislation introduced on the occupied peninsula by the self-proclaimed Russian authorities, all existing nature reserves were to be brought under the jurisdiction of the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources. Anonymous sources have told the UWEC Work Group that the self-proclaimed authorities planned to appropriate and develop land belonging to the reserve (primarily along the coastline in the south of Crimea) on a large scale from the outset. It turned out, however, that not only could reserves not simply be abolished, but control over them had to be transferred to the federal government. The Russian legislation came as a surprise to collaborationist officials, who were already planning to develop the area but were forced to submit to the new conditions. Over time, the self-proclaimed authorities of Crimea nevertheless found an opportunity to carve up the reserves in their own way, as will become apparent later in this article. The Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve can be used as a case study of the consequences of this activity.

Why is the Yalta reserve such a distinctive and valuable conservation area?

Situated in the southwest of Crimea, the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve occupies an area of 14,523 hectares. It was established back in Soviet times, in 1973 – around 50 years ago. Its territory extends west to east for 49 km along the Black Sea, from Foros to Gurzuf, surrounding the city of Yalta and its suburbs. The majority of Crimea’s most spectacular landscapes can be seen in this reserve. In fact, almost all the wilderness areas along Crimea’s southern coast are part of the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve. For more than half a century, the reserve has effectively protected Crimea’s southern coastline from development, preserving the status quo of this territory as a “resort alongside a nature reserve.”

Of course, the nature conservation value of the reserve far outweighs its role as a resort. The Yalta reserve’s vegetation spans four altitudinal zones and includes forests containing Greek juniper (Juniperus excelsa) and Atlantic pistachio (Pistacia mutica), which are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine and are not only unique “pearls” of Crimea, but also the oldest trees in Ukraine. The oldest of the junipers and pistachios found here are up to 2,000 years old.

The country’s largest forests of Crimean pine (Pinus nigra ssp. pallasiana) are also located here. In total, the reserve is home to no fewer than 1,364 species of vascular plants, 183 species of moss, 154 species of lichens and 1,733 species of fungi – some of the highest respective numbers among all Ukrainian reserves. It is far harder to estimate the number of animal species. However, with the help of the Biodiversity Viewer tool, 128 species listed in the Red Book of Ukraine can be counted in the reserve. Many of them are endemic species, that is, they are found only in the Yalta reserve and nowhere else in the world.

Rare species of orchid found in the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve. From left to right and top to bottom: 1. Himantoglossum caprinum, 2-3. Horned Orchid (Ophrys oestrifera), 4. Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium calceolus). Sources: dinasafina; sapsan; svetlana-bogdanovich; vyacheslavluzanov

Butchering the Yalta reserve: a plot years in the making

Returning to the challenges facing the reserve, the plans to develop it seem to have been gestating over a very long period and scandals relating to the issue arose from time to time throughout the period of Ukraine’s independence.

In 2018 part of Crimea’s protected areas were brought under the federal jurisdiction of the Russian Federation, including the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve. Later, on March 10, 2020 together with five other protected areas, the Yalta reserve was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Zapovedny Krym FGBU (Crimean Reserve Federal State Budgetary Institution) – a specially created body under the auspices of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation. Krymsky National Park was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Russian Presidential Property Management Department, and the Karadag Nature Reserve came under the jurisdiction of the Russian Ministry of Education and Science.

However, in this document the stated size of the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve was already diminished. It had been reduced from 14,523 to 14,459 hectares, that is, it was now 64 hectares smaller than before. Following this, information about recreational services appeared on the reserve’s website, and even a detailed map of routes that could be uploaded to a GPS navigator or smartphone.

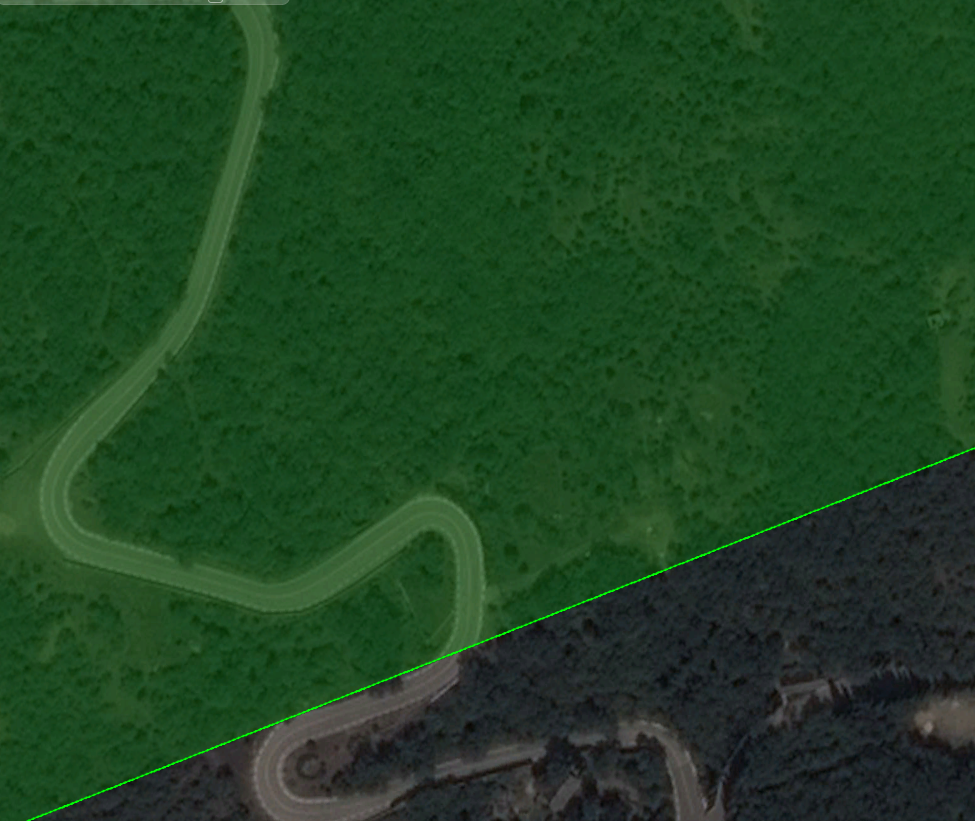

Overlaying a map of the current borders of the reserve with the full Ukrainian borders allows us to see precisely where carve-outs were made.

Satellite images taken in 2013 (а) and 2024 (b) showing the northern outskirts of the settlement of Olyva. Source: Google Earth

Satellite images taken in 2013 (а) and 2024 (b) show how a section of the reserve has been converted into a parking lot for the Mriya Resort & Spa complex. Source: Google Earth

One of the most striking examples of development on land reallocated from the reserve by the occupying authorities is the Lastochkino Gnezdo residential complex near Haspra. Building work began on the complex in 2014–2015. The developer’s website actively advertises the complex as being located close to Swallow’s Nest, a Neo-Gothic chateau on a clifftop overlooking the sea, and “surrounded on all sides by juniper groves.” This is unsurprising, since it has been built in the very location where junipers grew in the reserve.

That said, there have always been buildings within the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve, including those built for recreational purposes. However, the sectors of the reserve that were reallocated or sold for future construction were not located in the vicinity of older developments – they were tracts of wild land.

The speed with which the new territories around Yalta are being developed can be seen by comparing satellite photographs from different years. The scale of new construction since the Russian occupation began is clearly visible on the western outskirts of the city.

It is interesting to note that immediately prior to the events leading to the annexation of Crimea in 2014, then-president of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovich planned, together with Sergei Aksyonov (who subsequently became head of the occupation government in Crimea), to remove 700 hectares of the most attractive land from the reserve. No development had been allowed on land belonging to nature reserves in the years following Ukraine’s independence, so it was not easy to organize such a scam. Crimean officials had been laying the ground for the move for at least 7-10 years.

It was during this period that environmentalists became aware of Aksyonov, whose name they came to associate with attempts to develop parts of the Mountain Forest Nature Reserve. The plan was to “expand” the reserve through the signing of a corresponding presidential decree, but in reality this meant adding land of no interest to developers while simultaneously seizing 700 hectares on the southern coast for development. Prior to 2010, it was impossible to issue such a decree, since Viktor Yushchenko was in power. The most active of all Ukrainian presidents when it came to supporting protected areas, Yushchenko created the largest number of Ukrainian national parks in history, and took important steps to strengthen their protection. But as soon as Viktor Yanukovych became president, a draft decree on changing the borders of the Yalta Reserve was immediately drawn up. In the end, it was not possible to implement these plans, because Yanukovych ended up on the losing side during the Revolution of Dignity in 2014 and was stripped of his office after fleeing to Russia.

Nonetheless, the nefarious plans to seize land from the reserve came to fruition following the annexation of Crimea, in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution of Dignity.

According to the official data, the park has been reduced in size by only 64 hectares, although we wrote above that the plan was to remove 700. This is indeed the case. It appears that the land appropriation scheme is yet to be fully realized. While the map above, published on the official website of the reserve by the occupation administration, ostensibly shows the reserve to be just 64 hectares smaller than the “original boundaries,” in reality depicts an area that is at least 700 hectares smaller. A comparison of the reserve’s “Ukrainian” and “occupation” borders quickly makes everything clear. So we can expect subsequent rulings that will see the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve shrink even further.

The practice of stripping land from the nature reserve fund is in contradiction of Ukrainian state policy, and, at a time when there are global demands for the preservation of remaining nature areas, appears to be nothing short of barbarism. Of course, such steps are linked to the desire of the occupation administration to make use of those territories which have potential for the tourism and hospitality industry. Development is of course an extremely profitable activity, though of no benefit when it comes to the conservation of biodiversity.

Once Crimea returns to Ukrainian control, it will be impossible to return the land stolen from the Yalta reserve to its previous status, since it will already be destroyed. However, it will be possible to take other measures: firstly, to bring those involved in the appropriation and development of the reserve’s territory to justice; secondly, to prevent development plans not yet implemented from being put into effect; and thirdly, to expand the reserve into adjacent territory in the mountains. Such actions would serve as some kind of compensation and contribute to the conservation of those species that remain within the reserve.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image: View of the coastal settlements of Sanatorny and Foros from the Yalta Mountain Forest Nature Reserve. Source: Roman Pankov