Oleksiy Vasyliuk

Translated by Alastair Gill

The issue of restoring nature after the war is becoming increasingly relevant for Ukraine. On the one hand, it is important to understand the extent to which it is actually possible to restore the country’s damaged ecosystems. On the other hand, spontaneous restoration of vegetation is completely unpredictable and can cause concern, as the case of the Dnieper valley shows. While a natural floodplain forest on the site of the former Kakhovka reservoir may regrow, abandoned crop fields and ruined settlements could potentially become places where invasive plant species flourish.

Military activity has a wide range of destructive effects on natural and agricultural landscapes, including:

- munitions explosions;

- construction of fortifications;

- felling of forests for military needs;

- remains of destroyed equipment litter the landscape;

- passage of heavy, tracked vehicles;

- fires at explosion sites that spread uncontrollably; and

- chemical pollution of the soil.

All of these factors alter the existing landscape to the point of being unrecognizable, often with little remaining life.

The village of Andriivka in the Donetsk Region (a) during its liberation in August 2023 and (b) September 2023. In the first photo it is clear that there is no vegetation or small branches on the trees despite it being summertime. In the second photo, taken several weeks after the first, there is a visible increase of synanthropic, mostly invasive plant species. Source: Military Chronicle of the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade

At the same time, the destructive consequences are short-term, and in the long-term the fate of landscapes and biodiversity in polluted areas will be primarily determined by future human use. The long-term unavailability of land for economic activity as a result of occupation, and, especially as a result of mining, is leading to the spontaneous restoration of quasi-natural ecosystems on a large scale.

Even a few weeks without an intensive agricultural load are enough for an area to begin to become uncontrollably overgrown. Consider the amount of year-round weed control required in any garden plot, for example.

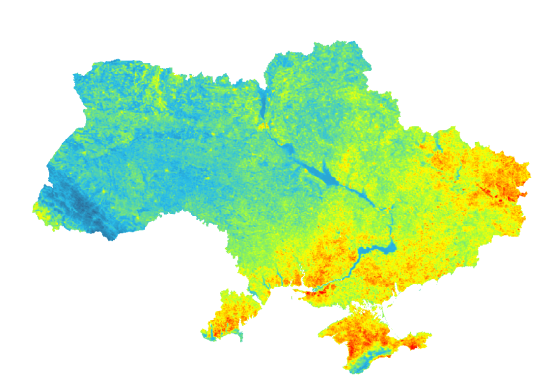

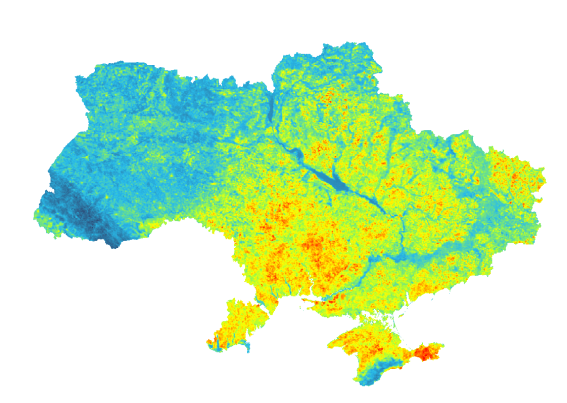

In fact, the scale of these processes is startling even now. A comparison of 2023 thermal survey data of the earth’s surface using MODIS spectroradiometers (during the active growing season) with similar periods from previous years shows that all areas that were the scene of hostilities, where fighting is ongoing, and mined areas have become zones of large-scale overgrowth.

Vegetation reflects sunlight and generally creates zones of moisture and coolness, while arable land and areas of open soil absorb solar heat, meaning they are not recognized by satellites as a heated surface. Working inversely, thermal imaging data can be used to obtain information about areas where there is no vegetation, areas where there is – and if there is, how much.

Such data can be obtained for any day. The best aerial thermal images of Ukraine are from 2021 and 2023. Imaging from the year 2022 should be discounted, since it was atypical: the lands were plowed but not sown, and there were also many fires.

Daytime surface temperature: summer 2021 (a) and summer 2023 (b). Source: Yevheniya Drozdova and Andriy Harasim

Intensive spontaneous overgrowth of vegetation is already occurring across a total of at least 1.5 million hectares of land, all of which is former fields and settlements where agricultural activity has ceased. In other words, an area 20 times larger than the Chornobyl exclusion zone is highly likely to have been overgrown by invasive plant species. For part of the territory, this change has taken place in a matter of months.

The colossal destruction to landscapes, land mines, and social factors (occupation and the migration of the population away from the zone of active hostilities) have created new conditions, in which plants and animals found themselves outside the scope of human economic activity for the first time in several centuries. For a second year now, fields have not been cultivated, no pesticides have been used, industry stands idle, and there are simply vast areas without any people.

But it would be wrong to romanticize this state of affairs and see in it the rebirth of wild nature. Apart from the fact that there are no more people in the destroyed villages, and farmers no longer work in the fields, the war has led to the colossal pollution of the soil with chemical products of ammunition, destroyed wastewater treatment plants, chemical plants, and heavy industry facilities, such as metallurgical plants. Most of the most dangerous industrial facilities in Ukraine happen to be located precisely in the zone that has been most heavily damaged over the past year and a half. Nevertheless, changes do occur in nature. And changes caused by military activity only contribute to the spread of synanthropic vegetation and invasive species.

A Sentinel satellite image from early summer 2023 shows the light-colored bed of the former Kakhovka reservoir, which was completely drained after Russian forces blew the dam in June 2023. And to the east of it (on the right of the photo) and then to the north is a large dark green zone covering a total area of more than a million hectares.

Director of programs for the Marjan Study Group in the department of war studies at King’s College London Jasper Humphreys has coined a new term for such changes: “war-wilding”. The story of war-wilding is one more of transformation than it is of recovery, as many think.

It is difficult to assess how the issue of nature restoration is perceived in the world as a whole, but in Ukraine the generally accepted opinion is that natural ecosystems easily return to areas abandoned by people – a view that stems largely from the aftermath of the nuclear disaster at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in 1986. After the accident, the local population was forcibly evicted from a vast area of northern Ukraine and southern Belarus, turning it into a deserted radiation-contaminated exclusion zone. However, natural ecosystems have now fully recovered in this area, and it has become the largest wild forest in eastern Europe.

The restoration of the Chornobyl ecosystems was facilitated by the presence of a large number of natural swamps and forests in the area, as well as generally humid conditions in the Polesye region. Beavers quickly blocked the drainage canals and wildlife returned to the radiation-contaminated territory, covering former fields and even villages with forest. Despite the radiation pollution, most wild species are thriving here today, and the Exclusion Zone has not become, as many feared after the 1986 disaster, either a “dead zone” or a “kingdom of mutants.” This may be because most wild animals have a significantly shorter natural lifespan than is necessary to experience the effects of long-term exposure to radiation.

There is another relevant factor: at the time of the disaster there were almost no invasive species in the marshes of northern Ukraine. Man once reclaimed these lands from the swamps, but as soon as he left them, nature quickly returned.

But the “Chornobyl experience” cannot be repeated in the south and east of Ukraine, where the vast majority of land has been regularly plowed for a long time, and where no more than 3% of natural steppe ecosystems – refugia of native fauna and flora – have remained in their natural state. And where, as a result of climate change, all roadsides have long been home to dangerous invasive species that are resilient to arid climates. Any handful of native soil contains more seeds from invasive species than native flora. So a rebirth of natural ecosystems can not be expected here. But there is a risk that all the abandoned settlements and fields already represent the largest ever precedent for the spread of invasive species. And the total size of areas overgrown with invasive species already significantly exceeds the area occupied by natural steppe ecosystems.

In the short term, then, invasive and synanthropic plant species will make up a significant part of spontaneous recovery processes. Before the war, these species typically spread only along roads and in forest belts (although they disperse seeds across all land types).

However, in some areas the opposite trend should be expected, particularly in intrazonal ecosystems. This term refers to steppe zone forests, which typically fill narrow ravines and river valleys in gullies. Forest ecosystems self-regulate moisture evaporation, creating a windproof zone under the dense canopy, a humid microclimate that supports the forest itself during dry periods.

The majority of invasive species are spreading across southern Ukraine as a result of general aridification – that is, gradual desertification. Such species are drought-resistant invaders from drier regions – herbaceous plants (Anisantha tectorum, A. sterilis, Rhaponticum repens, Portulaca oleracea, Opuntia humifusa, Aegilops cylindrica) and trees (Gleditsia triacanthos, Robinia pseudoacacia, Elaeagnus angustifolia). But, for example, other processes are at work in river valleys, where conditions are not arid and completely different kinds of biotopes are found there.

Studies of annual overgrowth on the bed of the former Oskil reservoir in Kharkiv Oblast showed that 63% of the plant species that overgrow new territories are native. Over time, native perennial species will further supplant single-year introduced species.

Regrowth of vegetation at the bottom of the former Kakhovka reservoir is underway. Of course, in river valleys, where conditions are unfavorable for drought-resistant invasive species, restoration mainly involves native species, as in the areas of wetlands and forests in northern Ukraine.

Ukraine is geographically large enough to have a variety of natural conditions, so at present it is hard to say what form war-wilding will take in different parts of the country. It was enough to dissuade UWEC Work Group experts from indulging in casual predictions to see that in the three months after the destruction of the Kakhovka dam, not only had thousands of young trees sprouted on its bottom, but also that these young trees had already reached human height. The question is – how will this territory look in 10 or 20 years?

In any case, the changes underway today are a unique experiment, allowing the study of spontaneous vegetation successions over unprecedentedly large areas that were recently inhabited and are now abandoned. In addition, there is also precedent for the massive spread of invasive species, on a hitherto unseen historical scale.

It should also be recognized that there are remnants of natural ecosystems among the abandoned areas as well as protected areas. These will serve as refugia for natural flora and support the spread of natural ecosystems to adjacent areas.

At the moment, it is unclear how long the partial occupation of Ukraine will last, much less the process of demining affected areas. According to preliminary estimates by the Ukrainian Cabinet of Ministers, demining will take more than 70 years. So it can be presumed that the very last post-war clean-up operations may take place in areas where a 70-year-old forest will already be growing, and mines will be buried deep in the soil under the roots of trees. Since this calls into question the feasibility of complete demining, UWEC Work Group experts propose that the most damaged areas, as well as environmentally protected sites, should be designated as special zones where demining will not be carried out at all. The spontaneous restoration of ecosystems in these territories could be seen as a powerful contribution to the fulfillment of Ukraine’s state conservation objectives for degraded lands, as well as the fulfillment of international obligations on combating desertification and climate change. After all, in practice all these tasks consist of restoring natural vegetation in places where it was degraded or absent.

In the coming decades, planning for scenarios combining development of new ecosystems and coexistence with humankind for land areas experiencing spontaneous vegetation recovery will be the central challenge and perhaps a stumbling block for expert biologists and land managers. Biologists and ecologists therefore find themselves in a very uncomfortable position: nature is not waiting for humans to act and is rapidly taking over land abandoned by people and environmentally damaged areas. Knowledge of the biology of these landscapes is now useful only for comparing the new reality with memories of the past. And, finally, for the present most of the areas damaged by the war are inaccessible, and it is possible that many will remain off limits until the process of demining them is complete.

Main image credit: Irish Times

Comments on “Restoring Ukraine’s nature post-war: Hopes and risks”