by Mikhail Rusin

In this article, the zoologist Mikhail Rusin describes the war’s direct threats (combat, bombing, earthworks, uncontrolled fires, mining, etc.) to endangered small mammals and assesses how these threats influence their survival.

The Russian war against Ukraine started in 2014 with Crimea’s annexation and support of separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk regions, at the heart of Ukraine’s steppe grasslands. The new phase began with Russia’s open, large-scale invasion on 24 February 2022. Although the primary goal of the invasion was to capture Kyiv, the invaders had fled northern Ukraine by April. Consequently, the majority of combat has occurred in Ukraine’s steppe zone: Mykolaiv, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, Donetsk, and Kharkiv Oblasts. The war does not differentiate between protected areas and croplands, nor does it worry about threatened species.

Small mammals at risk

Small mammals, in particular rodents, are often seen as something usual, common, and even negligible when it comes to nature conservation. While people often treat them as pests, zoologists and ecologists emphasize the huge role these tiny beasts play in ecosystems. (Further reading: https://bit.ly/rodents-defence). In European grasslands (often called steppes) rodents could be the only visible mammalian wildlife species. Some argue that Eurasian steppes are the most transformed ecosystems on the planet (Carbut et al. 2017; Hoekstra et al. 2005), yet it remains the least protected biome.

Is it unsurprising that rodents – the dominant mammal residents of steppes – faced significant population declines and became threatened with extinction. For example, in the latest list of protected species in Ukraine (often referred to as the National Red Book), 25 species of rodents are identified as threatened. And 18 species out of those 25 represent species strongly associated with Eurasian grasslands (Table 1). It is no surprise that besides the obvious humanitarian crisis, the war can have a tremendous impact on steppe ecosystems, especially on protected species.

Some of the species protected in Ukraine have a wide distribution, with Ukraine being the western limit. Such species are not recognized on the global level as threatened. There are some species endemic to Ukrainian grasslands, however, and those could easily go extinct if something goes wrong.

| N | Species | Red Book of Ukraine (2021) | IUCN Red List of threatened species (2022) |

| 1 | Marmota bobak // Steppe marmot | EN | LC |

| 2 | Spermophilus pygmaeus // Pygmy ground squirrel | EN | LC |

| 3 | Spermophilus citellus // European ground squirrel | EN | EN |

| 4 | Spermophilus suslicus // Speckled ground squirrel | EN | NT |

| 5 | Spermophilus odessanus | EN | n/a |

| 6 | Sicista lorigera // Nordmann’s birch mouse | EN | VU |

| 7 | Sicista cimlanica // Tsimla birch mouse | VU | n/a |

| 8 | Sicista strandi // Strand’s birch mouse | VU | LC |

| 9 | Allactaga major // Great jerboa | EN | LC |

| 10 | Stylodipus telum // Thick-tailed three-toed jerboa | VU | LC |

| 11 | Spalax arenarius // Sande mole rat | VU | EN |

| 12 | Spalax zemni // Podolian mole rat | VU | VU |

| 13 | Spalax graecus // Bukovina mole rat | VU | VU |

| 14 | Nannospalax leucodon // Lesser mole rat | VU | DD |

| 15 | Cricetus cricetus // European hamster | VU | CR |

| 16 | Nothocricetulus migratorius // Grey hamster | VU | LC |

| 17 | Ellobius talpinus // Northern mole vole | EN | LC |

| 18 | Lagurus lagurus // Steppe lemming | EN | LC |

Impact of the war on small mammals

Firstly, species not directly impacted by the war are omitted in this overview: European ground squirrel, lesser mole rat, and Bukovina mole rat. Their distribution area lies at a distance from the conflict zone, where only occasional rocket explosions may occur.

The steppe marmot is a story on its own. Prior to the war, the marmot population declined slowly (Tokarskiy, 2004), and despite some effective species reintroductions the core wild populations in Kharkiv and Luhansk experienced continuous degradation. Following the first invasion in 2014, hunting was banned throughout Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts (controlled by the Ukrainian government). A recent survey using satellite imagery showed a large number of populations of marmots in northern Luhansk Oblast (Vasyliuk, 2022), potentially indicating population growth (compared to Tokarskiy’s 2004 data). This increase surprisingly coincides with the ban on hunting.

Russia’s invasion in 2022 captured all of Luhansk and eastern Kharkiv Oblast. The Ukrainian counteroffensive in September liberated all of Kharkiv and even some small parts of Luhansk Oblast. Potential threats to marmots in that area include building fortifications in marmot colonies, intensive artillery barrages, and mining.

While direct killing of marmots by combatants is quite possible, it would not be expected to see a restoration of hunting under Russian rule: occupation forces would not permit armed locals to roam the area. Hunting with snares may happen, but that was the case under Ukrainian rule as well (all snare hunting in Ukraine is illegal). All in all, the situation with marmots remains controversial. Some populations could be extirpated due to direct destruction by the military (or locals), while some may benefit from the reduction in hunting.

Two species of ground squirrel are affected by the war’s activities. There are several speckled ground squirrel colonies close to sites that experienced severe artillery and aerial shelling between February and September 2022. At least two colonies were located near airfields in Mykolaiv and Ochakiv. These colonies were so small that a single FAB500 bomb could easily destroy a whole colony. Russian forces tried to capture the Mykolaiv airfield, and fierce fighting occurred there.

The author examined available Sentinel satellite imagery while writing this article and found no visible signs of these colonies’ destruction. Russia’s recent withdrawal of troops from Kherson reduces the risks of direct destruction of these colonies. Another threat lies in potential habitat degradation. Both colonies prospered thanks to grazing by livestock. Grazing activity on rangelands is critical for ground squirrels: they require short-grass pastures, and abandonment of grazing leads to tall-grass rangeland unsuitable for ground squirrels. It is possible that grazing was impossible or not allowed in 2022. Verifying the presence of that activity is not currently possible, in part because both sites are too close to military objects.

The pygmy ground squirrel is now present only in occupied areas of Ukraine. A few colonies were known to live in Crimea (iNaturalist observations data). Most of the colonies known in 2009 in Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Donetsk Oblasts, later appeared to be abandoned. The fate of colonies now located on lands controlled by the DPR and LPR is unknown.

All surviving colonies of ground squirrels are very small and fragmented, easily destroyed by any activity, particularly building fortifications and bombing. Mining in and of itself does not threaten ground squirrels, but may result in the absence of livestock grazing activity and thus quickly degrade habitats.

The great jerboa faces more or less the same situation. This species also requires grazing, although usually over a more dispersed area, so it is expected that they will be less affected by active combat. One of the most important areas for this species is the dry steppe habitat near Lake Syvash. No active fighting has occurred there to date, so at the moment, they should still be safe. The fate of colonies located on lands captured by DPR and LPR in 2014-2015 is unknown.

Similar to colonies of ground squirrels in Mykolaiv, military combat occurred in areas where Podolian blind mole rats were present, namely in southeastern Mykolaiv Oblast and western Kherson Oblast. The consequences of these battles are unknown, but hopefully the mole rats survive. The author received several reports of sightings near Ukrainian positions in Summer 2022.

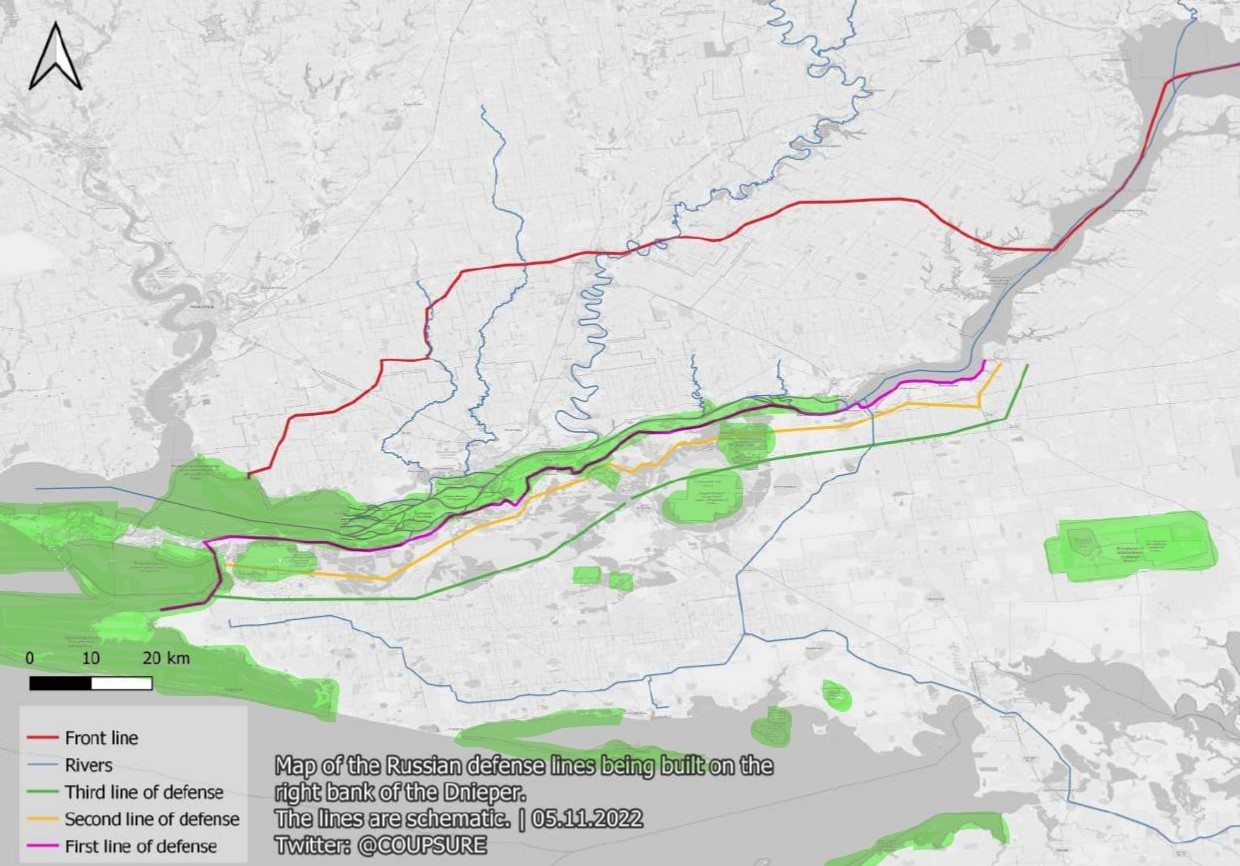

Several species can be grouped together based not on their taxonomy, but geographically. The Sands of the Lower Dnipro River are a really interesting place, hosting several endemic species of plants and animals. Among small mammal species, the sandy mole rat’s entire range falls within this area. The three-toed jerboa has an isolated subspecies S. telum falzfeini that may only be found here. And finally, by the author’s estimates, approximately 60-70% of the entire known (global) population of Nordmann’s birch mouse are found on the Lower Dnipro Sands. The recent withdrawal of Russian forces from the city of Kherson and all regions west of the Dnipro River resulted in intensified fortification of several defense lines. Although it is hard to validate the exact form of these lines of defense, one can imagine a long network of trenches and concrete fortifications, inter-connected by a huge number of unpaved roads. Some experts provided maps of these lines and show them crossing several protected areas, including the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, Oleshki Sands National Park, Sahi Refuge and several more, all very important for protected small mammal species.

Digging in sand is easy, making it equally easy to destroy this habitat. The new road network, created using heavy vehicles (both construction and military equipment), results in desert-like landscapes. Construction of these defense lines alone may have disastrous effects for protected species, and continuous shelling and fires are additional threats.

The European hamster is the only species with a global Critically Endangered status in the region. It is affected only subtly, with most of its active populations outside of war-torn regions. The largest population of European hamsters in Ukraine was in Crimea. After the peninsula’s annexation, the hamster lost its protected status, as the Russia-controlled government does not recognize the Ukrainian Red Book. That said, no real conservation happened there under Ukrainian control either. Some small populations are known to exist near Mykolaiv and Kharkiv, so some losses could occur due to the war, but to what extent is impossible to say.

In contrast, a significant portion of Ukrainian distribution of the dwarf hamster falls within war-torn areas, from Mykolaiv to Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Luhansk. Some dwarf hamsters could be directly killed during large-scale artillery barrages. The other threat is the huge number of trenches in the area. Trenches create pitfall traps for small mammals, affecting every species mentioned in this article. The presence of dwarf hamsters was recorded at least twice in trenches. In one case, Ukrainian soldiers removed a hamster from their trench. In another case, a Russian soldier killed and hanged the dead body of a dwarf hamster. Such poor behavior could pose a threat to other species as well.

The mole vole is protected in Ukraine, with approximately 90% of its population located in Crimea, 5% in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, and another 5% in Luhansk. In spring and summer 2022, 99% of all populations were located in occupied areas, with the only population outside occupied areas located near Nikopol in Dnipro Oblast. Later, the counteroffensive liberated all mole vole populations west of the Dnipro River. Numerous fierce battles occurred in places where mole voles were previously known. All of these colonies were small and thus at risk from explosions and construction of fortifications. Of all the species discussed here, the status of these populations would be the easiest to verify in the near future.

Before the war, the Strand’s birch mouse was recorded in just two localities, both in eastern Luhansk Oblast within Luhansk Nature Reserve. In Provalskyi Steppe (located in the southern part of the region and held by LPR since 2014) birch mouse was most recently documented in 2009 and then seen again in Striltsivskyi Steppe (a northern area that remained free until 2022) in 2018. Strand’s birch mouse lives in bushy steppes. Thanks to occasional reports from locals, the habitat in Provalskyi Steppe is known to have survived intact, so we hope that the species will survive the turmoils of war.

Lastly, the steppe lemming has probably been extirpated in Ukraine. The most recent reports of its presence came from Luhansk and Kharkiv long before the war began. Some of its areas of known habitation lie in areas of current or former battlegrounds, and this further reduces their potential survival in Ukraine.

The war has a terrible impact on nature conservation efforts. Many protected small mammal species have fragmented distribution, occupying small and isolated colonies. The smaller the colony, the higher chances are for its destruction during the war. Larger shells and rockets could easily destroy an entire colony of some species with a single blast. Trenches pose threats to almost every species of protected small mammal. The presence of many armed people living under extreme stress may result in many animals being killed for no reason. Degradation of habitats is an ongoing threat. Time will tell, and monitoring continues.

Mikhail Rusin works as a researcher at Kyiv Zoo, Kyiv, Ukraine and at Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Comments on “Threats of Russian invasion for protected small mammals in Ukraine”