On the second anniversary of the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, we asked our editorial team members to comment on the war’s most important environmental consequences and the issues they believe merit our readers’ attention. The war in Ukraine has been going on for ten years, but the last two have been the most catastrophic for both the country and the whole world.

Aleksei Ovchinnikov, UWEC Work Group editor

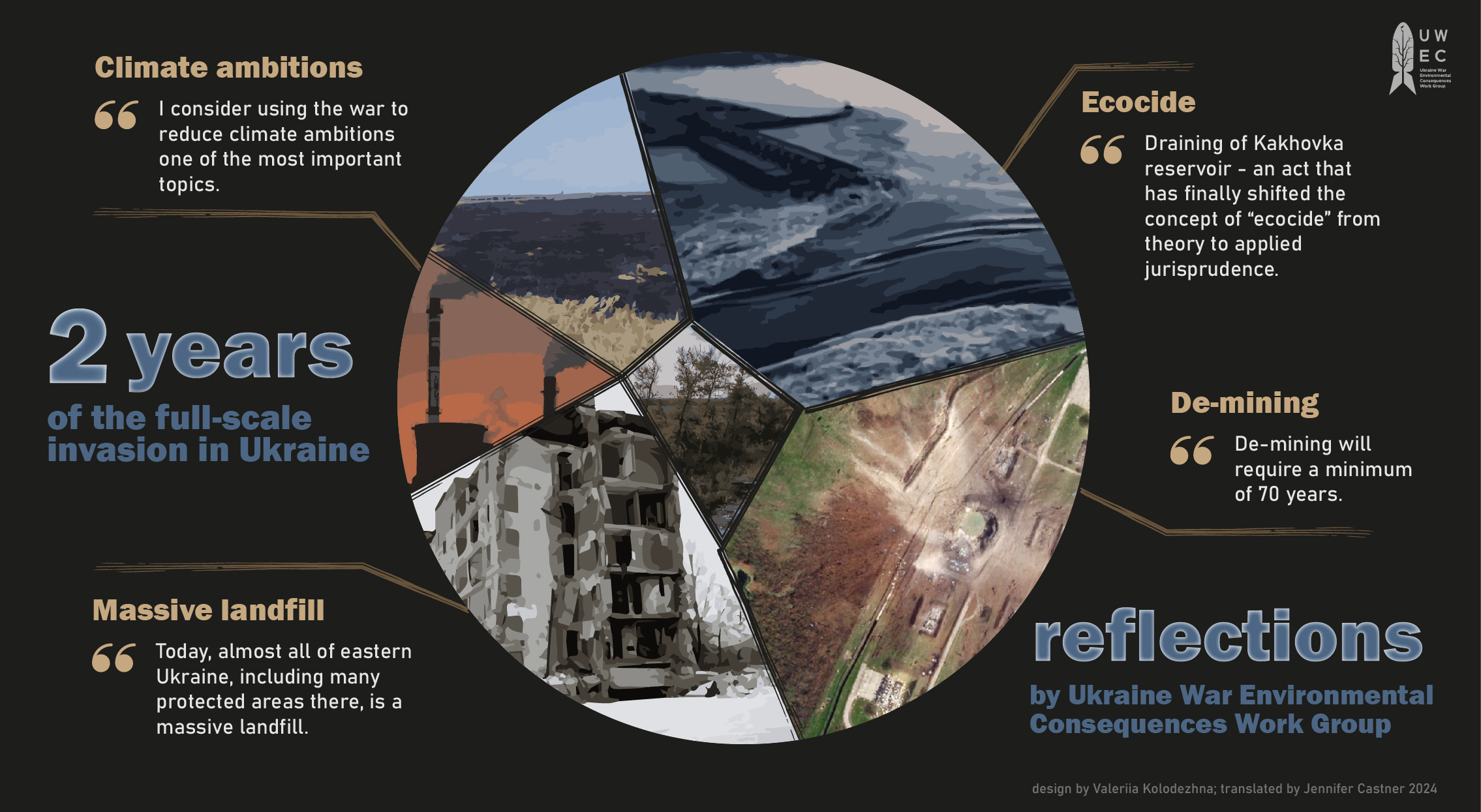

I consider using the war to reduce climate ambitions one of the most important topics, whether the excuse be issues of energy security, food security, or militarization in anticipation of the “beginning of a third world war.” There is a clear trend today in lowering climate ambitions in many countries, from the European Union to Russia. War and political (economic) security are seen as the greatest priorities. I think this is misleading. Today, climate change poses the greatest danger to global human society (not nature). With each passing year, we see the consequences, and the likelihood of intense abnormal weather events only grows. February’s broken temperature records are one confirmation. To end this war, we must not lose focus on climate change adaptation and mitigation and we must take meaningful actions, not fictions. Otherwise, war, forced migration, and political instability will become a permanent backdrop in today’s world.

I’d also draw readers’ attention to something that often remains below the surface: war generates mountains of garbage. This waste consists not only of destroyed houses and roads and burned military equipment, but also mountains of single-use packaging, bottles, boxes, etc. Today, almost all of eastern Ukraine, including many protected areas there, is a massive landfill. Given the density of minefields, it will take decades to address that waste. We must begin to identify solutions for processing this waste today, for example, recycling it for use in Ukraine’s reconstruction.

Eugene Simonov, UWEC Work Group expert

The main difference between the first anniversary and this one is the understanding that this war, and the daily environmental damage it inflicts, will apparently be with us for a long time. A year ago we seriously hoped that we would solve the war’s accumulating problems after a quick victory. Today, when I read bright-eyed remarks at the end of articles noting that accumulated damage or a tricky issue can be dealt with “when this all ends,” I resist internally. It is very likely that the war will continue for a very long time, and environmental problems will have to be addressed without waiting for victory. Furthermore, solutions must be based on the limited information, resources, and capabilities we currently have available.

This conflict is clearly visible in the example of the draining of Kakhovka reservoir – an act that has finally shifted the concept of “ecocide” from theory to applied jurisprudence. We can and will argue with officials and hydropower engineers at length about whether the reservoir must be restored, but both sides understand that a practical solution to this issue will likely be postponed until hostilities end. At the same time though, people living on the shores of the former reservoir have immediately faced a full range of severe socio-ecological consequences: lack of water, localized climate changes, catastrophic transformation of their home landscapes, and the disappearance of recreation and fishing areas. We need to help people find effective ways to adapt and learn from each other now, and not delay until “after victory”, … at least in territories controlled by Ukraine. For example, new efficient water supply systems, unconnected to a reservoir, must be created now, and not after a hypothetical “restoration of Kakhovka hydroelectric station.” Life along the lower Dnipro River should continue, rather than freeze in anticipation of a rebuilt Soviet-era dam 10-15 years down the road.

Similar issues arise and are addressed in other war-torn areas, primarily related to minefields in natural and agricultural landscapes, as well as against the backdrop of the frequent fires that occur during shelling.

At the same time, we are gradually accumulating experience in solving environmental issues in wartime. Looking ahead, UWEC Work Group’s mission will be to seek and promote those solutions and adaptation tools that help people and nature to at least partially overcome this ongoing horror.

Oleksiy Vasyliuk, UWEC Work Group expert

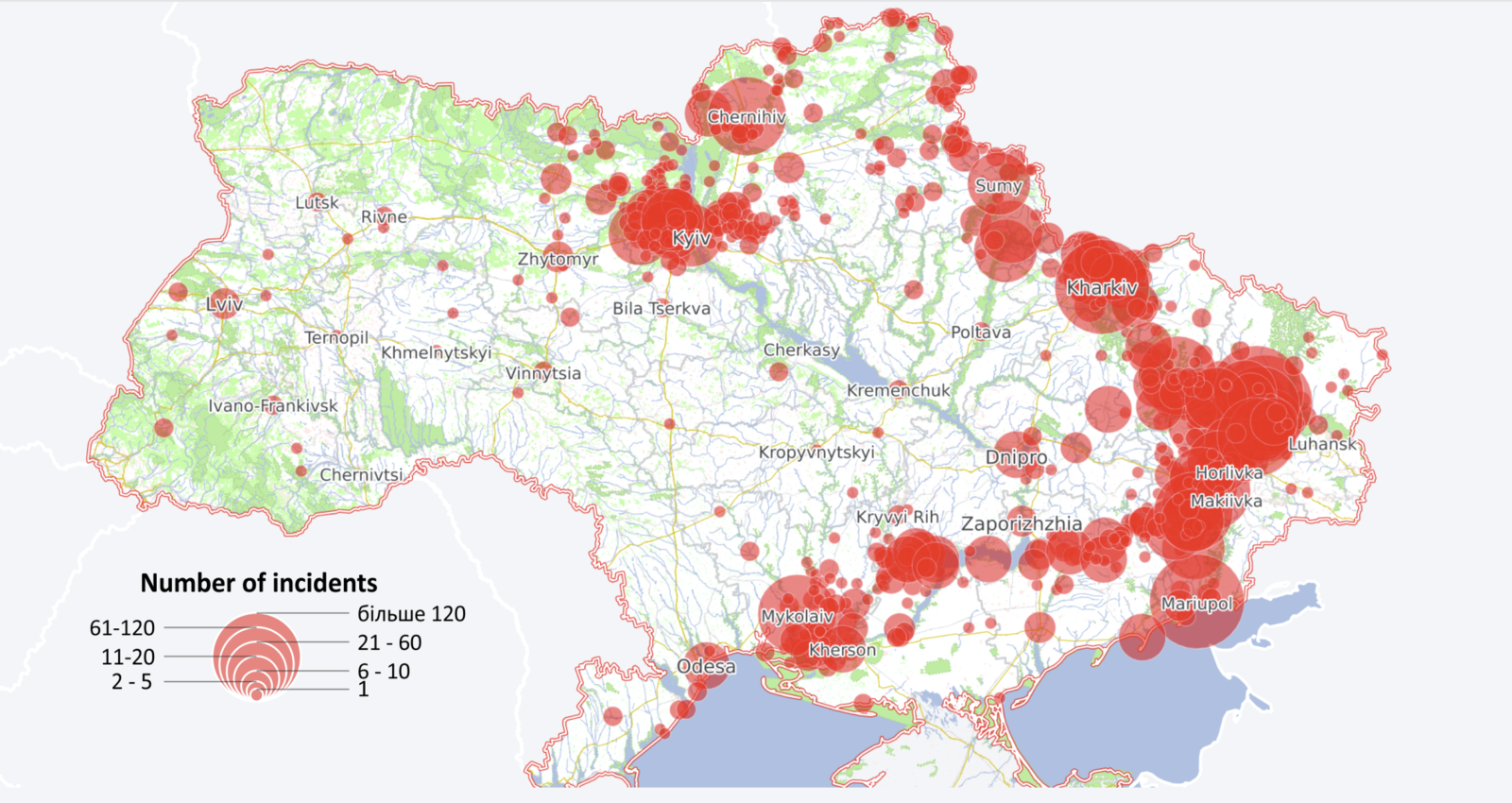

The prolonged war, long-term inaccessibility of temporarily-occupied territories, and incredible saturation of lands with explosive munitions (both unexploded shells and deliberate minefields) all eliminate the chances for a straightforward restoration of natural and agricultural territories after the war and occupation end.

The land area of Ukraine requiring de-mining already exceeds an area the size of Austria and Switzerland combined. De-mining will require a minimum of 70 years. Consequently, it is quite possible that some more contaminated and damaged areas would be more appropriately set aside forever (or for a very long time) in an exclusion zone. Unlike the bed of the former Kakhovka Reservoir (where nature is returning), these territories are overgrown with drought-resistant invasive plant species originating on other continents that pose a danger to local ecosystems and may result in radical transformation of entire landscapes in affected areas.

Regardless of the speed of de-occupation, Russia has de facto already deprived Ukrainians of part of their country, rendering some lands objectively unsuitable for habitation and use. Prior to the invasion, these areas were home to at least 7 million people.

It should also be noted that delay in assisting Ukraine with the de-occupation process will result in institutional degradation of the environmental conservation sector. Environmentalists and conservation workers are leaving the country or dying as soldiers in Ukraine’s Defense Forces. There is a colossal crisis in the availability of specialists capable of planning for Ukraine’s restoration and monitoring its “green” status.

Looking back at these two years, I would like to state first that this is a period of enormous losses: land, ecosystems, heritage, and people. It should also be noted that Ukraine’s demographic losses in the 20th century are also linked to Russia’s imperial aspirations: forced deployment of Ukrainians in its war against Finland, collectivization, resettlement, repression, and the Holodomor. All have radically shrunken the number of Ukrainian intelligentsia and specialists across all disciplines and sciences.

Over these two years, spiraling history is again taking away the best people. Today, the most conscientious people are dying: those who were the first to voluntarily defend Ukraine. This fact is a significant threat to the quality of Ukraine’s post-war restoration.

Finally, in the first months of the war in 2022, news media predicted that this war would become the most documented in history. Today, we know this to be true. It is quite possible that humanity will use the outcomes of Russia’s war in Ukraine to reflect on the losses suffered by nature as a result of other past wars.

Comments on “Two years of the full-scale invasion. Reflections on environmental consequences”