Do sanctions on Russian gold have conservation impacts?

As Western countries impose ever more sanctions on Russia, questions about sanctions’ environmental consequences become more urgent. These consequences differ from sector to sector and are often far from obvious or clear cut. This article will attempt to understand how the sanctions affect gold production and how those impacts are fraught for both nature and local residents in gold-producing regions.

Gold under sanction

Meeting in June 2022, G7 nations announced that the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Japan would impose a ban on gold imports from Russia. Australia joined them, and the European Union promised to discuss a ban for its next packet of sanctions. The import of precious metals from Russia is also now banned. As with all those before them, the goal of this new round of sanctions is to deprive Russia of financial means to make war in Ukraine.

Russia is among the three largest gold-producing nations globally, second only to China and Australia, and is responsible for roughly 9% of world production. In 2021 alone, Russia extracted approximately 340 metric tons of gold and exported 85% of that amount.

Last year gold was also among Russia’s main sources of export earnings, after oil, natural gas, and agricultural exports. Still, total gold earnings were about US$18 billion, representing a relatively small share of total export earnings (US$498 billion).

In response to US sanctions against Russia after its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Moscow began to increase its gold and foreign exchange assets. Now, various estimates indicate that Russia has approximately US$140 billion in gold reserves, roughly a fifth of the Russian Central Bank’s assets (holdings). In 2020, the Central Bank stopped actively buying gold and forcing companies and banks to export it. By the end of 2021, Russia ranked fifth in global gold reserves.

As a whole, Russia’s gold mining industry contributes significantly to its overall budget, producing over 1.3 trillion rubles (over US$21 billion in 2021) of gold and remitting numerous taxes and fees into federal coffers. The Mineral Extraction Tax alone brings in almost 80 billion rubles, and total payments to Russia’s treasury amount to at least 20% of all gold sold.

Gold and/or nature

Environmentally speaking, gold is a very “dirty” product, the extraction of which is usually associated with destruction of landscapes and river pollution. In addition, such mining is often associated with corruption, criminal schemes, oppression or forced relocation of residents (often Indigenous) living where deposits are found, and sophisticated exploitation of workers. This is a worldwide problem, one that forces the largest buyers and gold processors to monitor supply chains in order to ensure that the resulting gold is not “tainted” with human blood or the destruction of valuable natural ecosystems.

In Russia, environmentalists are well aware that the greatest harm to nature and local communities is caused by small mining brigades extracting alluvial (placer) gold in primitive and barbaric fashion: dredging sediments in river valleys, leaving barren landscapes over many kilometers of a riverbed, and also causing chronic clouding of rivers downstream of extraction zones. Only 15-20% of all gold in Russia is mined in this way, but such operations account for the lion’s share of environmental damage.

Large companies use more advanced processes to extract gold from ore. Their mines occupy a much smaller area and, as a rule, are subject to much closer government oversight. Although each individual site presents significant environmental risk, especially when accidents occur, overall (especially per kilogram of gold produced), they result in significantly less damage to natural ecosystems and are less devastating for local residents.

According to Viktor Tarakanovsky, chair of Russia’s Gold Prospectors Union, just 43 companies produce 84% of processed gold in Russia, and the remaining 550 enterprises contribute a lowly 16%. For the most part, those latter enterprises are small placer mining brigades operating on rivers.

Despite the fact that Russian authorities are well aware of the disproportionate harm caused by these small-scale alluvial operations, they encourage it to this day. Almost any organization can obtain a “prospecting license” for a pittance without formal tender or auction, allowing prospecting and test mining at one’s own risk in a river of one’s liking.

UWEC has already reported on how environmental law violations by this category of miners increased significantly in 2022, when their operations were decreed free of state environmental oversight during the war. Thus, the question of how sanctions and other wartime factors will affect the damage caused by gold mining is of great concern to Russian environmentalists.

Blow to exports

The most effective measures to block Russia’s gold exports were actually taken immediately after hostilities began. In early March, the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) “temporarily” stripped the largest Russian gold refineries of their “Good Delivery” seller status.

Almost all legal gold is refined at just a handful of refineries. The LBMA decision affected ingots produced at Krastsvetmet, Novosibirsk Refinery, Uralelectromed, Prioksky Non-Ferrous Metals Plant, Schelkovo Secondary Precious Metals Plant, and Moscow Special Alloys Plant.

“Good Delivery” status is awarded to refineries and producers of weighted gold bullion that comply with LBMA requirements. Gold from such suppliers is not subject to additional checks and can be freely traded on the London Metal Exchange (LME) and other Western trading floors. Without such status, selling gold in the UK and other Western countries is almost impossible, while, in other parts of the world, sales are possible, but at a significant discount.

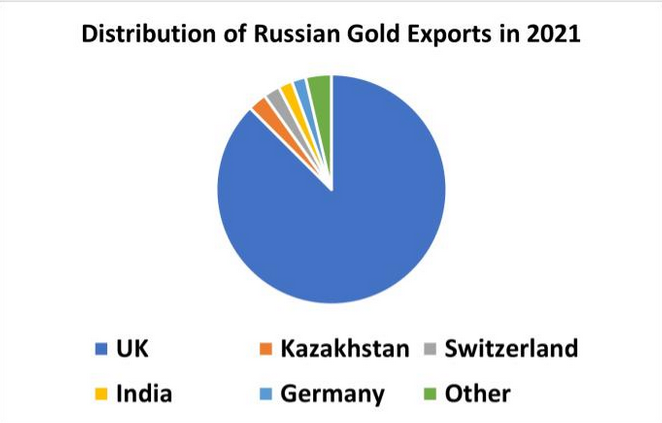

That said, London is not the only global center for the precious metals trade. Gold can also be sold at auction in Dubai (UAE), Shanghai (China), and Mumbai (India). The trouble, however, is that by 2021 approximately 90% of Russian gold exports went to the UK and other Western countries, and it is quite challenging to redirect sales to new customers.

Industry expert Leonid Khazanov told Oktagon-Media, “Our players will seek to increase exports to the United Arab Emirates, India, and China, albeit at a discount. In 2021, demand for gold in India approached 800 tons, while in China it exceeded 1,100 tons. In the most conservative scenario, we can expect a 30-40% decline (200-230 tons) in production by the end of 2022 and a resulting export reduction of 20-30%.”

Sanctions against many Russian banks played the most important role in declining exports. The first to affect Russian gold transactions – and thus the Russian Central Bank – were introduced on March 24 by the US Treasury. Subsequently, sanctions targeted precisely those large banks that were intermediaries for the sale of most Russian gold abroad.

Likely buyers

Thus, even before the introduction of G7 sanctions, gold sales abroad dropped dramatically. Chair of the Russian Union of Gold Producers Sergey Kashuba commented that at present most gold is now sold on the domestic market. According to Kashuba, the two main Russian consumers of gold are the domestic jewelry industry (which in previous years consumed 30-35 tons of chemically pure gold), and citizens, who, after personal income and value-added taxes were abolished, altogether can afford to buy only 25-30 tons of gold.

The Russian state abolished a 33% tax on gold in order to make the metal an attractive alternative to holding foreign currency. So far, however, individual demand for gold has plateaued, in particular due to high price volatility as well as the challenges facing individuals when it comes to selling gold back to banks.

Russia’s Central Bank has also begun buying up gold to replenish gold and foreign exchange reserves, but is doing so at a 15% discount on the market price. According to the Union of Gold Producers, the bank implemented this strategy from May 16 to June 10, 2022, when global gold prices fluctuated between 3,345 and 3,968 Russian rubles per gram of gold. During that same period, the Central Bank was purchasing gold at prices of 2,842-3,198 rubles per gram.

The scale of possible reductions in production also depends on how much gold the Central Bank is prepared to buy in reserves in 2022. At an industry conference in May, Russia’s Gold Prospectors Union Chair Viktor Tarakanovsky complained that the state’s planned purchasing volume is small: “In the State Precious Metal Repository’s three-year budget, they plan to purchase just 8 tons of gold, with no public plan for where to put another 350 tons.”

Discovered by journalists and NGOs, a delivery of 3 tons of Russian gold to Switzerland caused an uproar in May 2022. Swiss customs officials refused to disclose the metal owner’s name, reasonably noting that there is no legal ban on such imports. All Russian refineries have denied responsibility for this bullion, neatly illustrating the sector’s extreme sensitivity to the slightest suspicion of possessing “dirty gold.” Most likely, the gold’s owner simply brought gold purchased or extracted prior to the sanction’s effective date to Switzerland for storage, but even this information caused a sharp public outcry.

Companies exporting to non-Western countries are also experiencing difficulties. For example, JSC Polymetal (Polymetal Int subsidiary), a business that sells 50% of the gold it produces to Asian countries, saw its stock value fall by 74%.

Some experts detect an eastern trade vector increasing despite the threat of secondary sanctions.

“Today, Russia is already seeing a surge in gold trading with the United Arab Emirates. We are shipping ingots to Dubai on a massive scale. India and China will soon be included,” commented Golden Mint House vice president Alexei Vyazovsky during an interview with Vzglyad.

Resilience of Gold Mining Companies

According to the Union of Gold Producers, corporate ruble revenue fell by one-third due to a strengthening ruble and because the price of gold is pegged to the international exchange rate in US dollars. There have also been increases in almost all production cost categories. In 2022, the most significant growth is expected in exploration (40%), raw materials and materials (30%), and growth in wages and social needs (15%). Rising prices for saltpeter, a key ingredient in explosives, has already risen between 200 and 400%, a reflection of its wartime scarcity.

The price of gold is lower than the cost of production for most companies in the industry, especially for alluvial gold miners who had already begun their seasonal work when the ruble was ultra-low.

Many foreign mining equipment manufacturers and suppliers, including Komatsu, Caterpillar, Liebherr, and John Deere, “temporarily” left the Russian market, creating a significant potential challenge for accessing equipment and parts. While deliveries of Chinese equipment and South Korean equipment of Chinese assembly continue, these products will cost more and perhaps be less reliable than the previously available range.

Many foreign companies operating in Russia managed to acquire a large fleet of new equipment in 2021 and would now be happy to transfer them to mines in other countries. Speaking in the State Duma, Ministry of Natural Resources Minister Alexander Kozlov noted that he had signed an order limiting the export of foreign exploration, mining, and laboratory equipment.

“Many rushed to export this equipment outside our country, especially companies with foreign capital. In the last three months, we have issued only 16 export permits, refusing 70 more. Roughly 400 more applications are now under consideration, and we are interpreting them in favor of the state,” the minister added.

Mangazeya Mining Ltd, a Russian gold mining company with assets in Transbaikal, a Russian region east of Lake Baikal, has halted trading on the Canadian securities exchange. Delisting is a fate likely awaiting other companies that continue to do business in Russia.

General Director of Krastsvetmet (open joint stock company) Mikhail Diaghilev sees the situation as complex but not critical, given that large subsoil resource users producing the lion’s share of gold have a significant safety margin. But the Russia’s Gold Prospectors Union chair Viktor Tarakanovsky believes that difficult times are here for small companies. As a rule, that means small alluvial gold companies.

He asks, “We have 11 enterprises that do not produce even a single kilogram per year. Another 55 produce 1-5 kg, and 61 more with just 5-10 kg. Taken together, 127 companies produce approximately a ton of metal…. Where will they sell the gold?”

The Association of Subsoil Users in Magadan Region sent a written cry for help to Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Trutnev: “Small and medium-sized gold mining enterprises are at particular risk, given the time and difficulty of obtaining a general export license and signing contracts with foreign buyers, while still accounting for complex sanctions. It could be impossible or take a long time. Magadan miners explain that the consequences may be criminalization of gold mining or up to a 40% decline in annual production (120 metric tons per year) and subsequent loss of up to 40,000 jobs in Russia’s eastern regions.”

The Association’s letter cites compelling statistics: “In 2021, the average cost of gold mining in Russia was 1,700 rubles per gram, and, including capital costs – 2,450/rubles per gram. On the market, gold cost 4,340 rubles per gram, providing businesses with a profit for doing business and servicing financial obligations and investments. In 2022, however, inflation increased expenses by 490 rubles per gram, while the strengthening ruble reduced profits by 1,082 rubles per gram. A Central Bank discount reduces profitability by another 489 rubles per gram, rendering the direct sale of gold on the domestic market unprofitable.”

Despite all the difficulties, the Russian Statistical Services agency reported that in January-May 2022, Russian gold production fell by only 4.6% compared to the same period in 2021. As a side note, this may be the last official data on Russia’s gold production: companies no longer publish quarterly results, and in July the State Duma adopted a law declaring information about the country’s gold reserves as a state secret.

Russia’s potential responses

Of course, gold industry representatives are actively encouraging Russia’s Central Bank to eliminate the 15% discount on gold purchasing, a move that would significantly increase mining profits.

“From 2006 (until 2020), Russia’s Central Bank actively bought gold from subsoil resource users for the global price minus a 0.5% discount, and now is the time to resume this practice,” says Sergey Kashuba.

In order to avoid bankrupting the majority of small mining enterprises, Russia’s Gold Prospectors Union proposes to establish state guarantees for the sale of mined gold in accordance with the federal law “On Precious Metals.” To this end, the Union also calls for increased funding to purchase gold from miners for deposit into state reserves through the State Precious Metals Repository and the National Welfare Fund, up to an annual maximum of 300 tons of gold.

The Central Bank also recently publicly acknowledged the benefits of gold. “Gold is good because it cannot be seized,” noted Elvira Nabiullina, head of Russia’s Central Bank on June 29. “It can be wholly stored within Russia, and in that sense it is more secure. Of course, it must also be understood that gold prices are quite volatile. This must also be taken into account.”

Whether such a proposal would then be followed by Central Bank gold purchases is unknown.

Some economists believe that G7 sanctions are aimed at preventing the active use of Russian gold reserves.

“Russia could pay for essential goods not made at home using domestically produced precious metals. This is especially true in the face of a tightening embargo on Russian oil and gas. Approximately 21% of foreign exchange reserves could be used to pay for critical imports. But under sanctions, this will not be possible,” said economist Tatyana Kulikova, an employee of the Steklov Mathematical Institute, in a conversation with Gazeta.ru.

According to Kulikova, Western countries have also banned gold exports to the Russian Federation, as they seek to halt Russia’s ability to sell oil and gas for gold received in advance.

The Ministry of Natural Resources has drafted a bill to protect Russian partners in the event that foreign businesses unilaterally halt their activities in joint projects. Indeed, sanctions have already forced Canada’s Kinross Gold to sell its Russian assets; Polymetal Int split into Russian and Kazakh divisions; and Petropavlovsk (another major mining company) was unable to pay its debts to a sanctioned Russian bank. Under the new bill, non-residents are prohibited from obtaining a license for the use of subsoil resources in Russia. According to the Ministry of Natural Resources, this will force investors to register a Russian company and thus prevent possible unpredictable behavior by owners.

Boris Kavchik, a researcher at mining engineering research firm Irgiredmet, proposes to evaluate the Subsoil Resource Management Agency’s efforts not by the number of articles, projects, and reports, or even gold resources, but by increased real gold production, trouble-free operations, and environmental protection. He considers further simplification of the gold mining licensing process and ridding miners of petty state oversight the most promising moves.

Indeed, fears of rising unemployment during the war probably hastened preparation of the draft law “On Prospecting” at the Ministry for Far Eastern Development. The law will allow private individuals and entrepreneurs to prospect for and extract precious metals at prospecting sites “in a non-industrial way” in Russia’s Far East and Arctic zones. People will individually select and register sites where they want to mine gold. Oversight will be minimal.

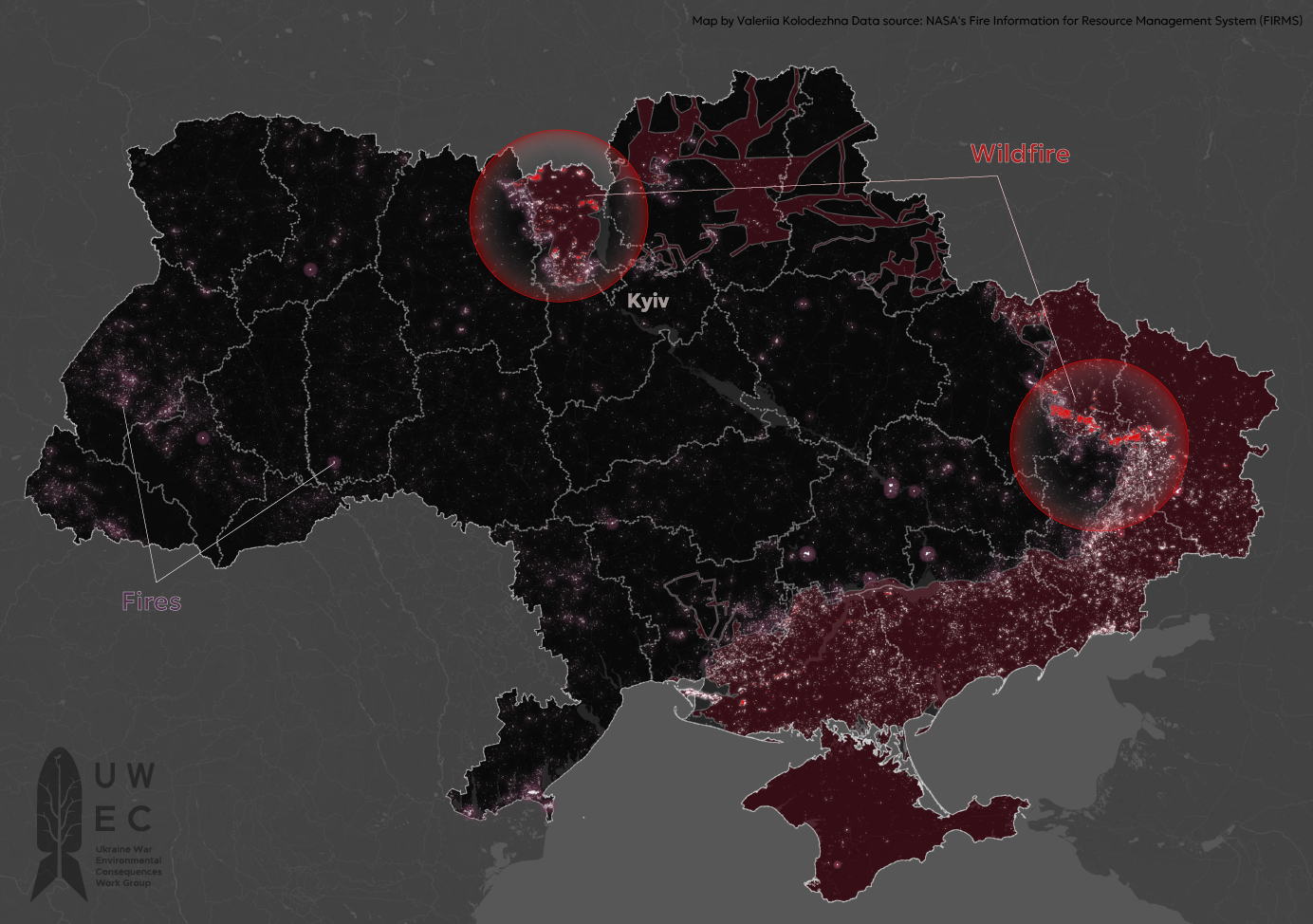

Natural consequences

According to public monitoring funded by WWF-Russia, in just one 30-day period from May 15-June 15, 2022, the extent of riverbeds disturbed and polluted by mining in eight Siberian and Far Eastern regions totaled 2,949 km of rivers across 85 different sites. This exceeds the same time period in 2021, where 2,534 km of rivers were polluted at 74 locations. The greatest number of pollution sites was documented in Amur Oblast (37 cases, 1,251 total km).

“Unfortunately, this year we are seeing increased negative impacts from alluvial gold mining on many rivers in Siberia and the Far East. While understanding the importance of strategic raw materials for the Russian economy, we support limiting extraction of alluvial gold, a process that damages ecosystems and is conducted in violation of environmental laws,” noted Alexey Knizhnikov, WWF program manager for corporate environmental responsibility.

Responding to increased environmental damage caused by gold mining and subsequent widespread public discontent, the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation announced its recommendations to the government on “Environmental Aspects of Alluvial Gold Mining” at the end of June.

These include a moratorium on issuing simplified (declarative) prospecting licenses, often used by miners to conceal illegal exploitation of placer gold deposits. The Chamber also requested a ban on licenses for exploration and production of alluvial gold in areas located within 5 km of a protected area boundary, as well as on rivers flowing through protected areas and territories of traditional natural use management by Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East.

So, despite sanctions that came into force only after companies commenced mining activity in 2022, environmental damage is unlikely to decrease in the coming months. An uncertain future is prompting companies to intensify current production; gold is always an important resource for survival. In addition, mining enterprises will also violate many environmental standards, given that oversight agency Rosprirodnadzor has sharply reduced the number of on-site compliance inspections.

If the Central Bank does not fully resume buying gold from domestic companies, then it is likely that a significant number of small and medium-sized companies will face bankruptcy, a trend that will effectively reduce destruction of new natural areas. In addition, next year, many companies will relinquish licenses for remote and inaccessible fields, where mining could potentially cause the greatest environmental damage. Total gold production is likely to decrease (perhaps 20%-30%), as large companies will sooner or later find alternative markets.

On the other hand, if the State Duma passes a law this fall allowing citizens to engage in individual “prospecting” activities, the law will result in active criminalization of the industry in 2023 by allowing the sale of gold of unknown origin. Many unemployed miners will become individual prospectors and head deep into the taiga forest, where the methods and scale of mining cannot be readily monitored. There is no doubt that heavy equipment and blasting could be used for such mining, although nominally the law forbids this. Such methods will not significantly increase production volume, but will deal a mortal blow to remaining taiga rivers. Placer mining and resulting river pollution are already sources of broad community discontent in many regions, and that discontent will intensify many times over with the potential adoption of the new law and start of this latest “gold rush.”

Freehold prospecting will begin work at alluvial deposits holding up to 20-30 kg of gold reserves. Their exploitation using traditional industrial methods is economically inefficient under current market conditions. According to Interfax News Agency estimates, there are at least 10,000 such non-industrial scale placer gold deposits across Russia. Environmentalists estimate that most of these sites are pristine river valleys in remote wilderness areas. The only potential silver lining is the hope that some young people from economically-depressed regions in the Far East (for example, Buryatia and Transbaikal) might become individual miners instead of enlisting to fight in the war.

In the event that the Central Bank opts to increase gold and foreign exchange reserves and purchase all domestic gold production without a discount, Siberian and Far Eastern nature wilderness will face even greater losses.

Environmental damage from gold mining depends not so much on the sanctions as such, but on the Russian government’s response to them within the framework of Russian domestic environmental and economic policies in wartime. And, as evidenced by the federal decree № 336 (10 March 2022) canceling compliance inspections, the Russian authorities are more likely to shift the war’s costs onto nature.

Translated by Jennifer Castner.

Comments on “War-time gold rush”