By Valeriia Kolodezhna and Oleksii Vasyliuk

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Ukraine has submitted 15 requests to exclude the Russian Federation from international environmental conventions. There is no consensus among experts in support of such initiatives, given that such exclusion poses tremendous risks for countries on either side of the Russia-Ukraine border. UWEC Work Group examines these concerns through the lens of transboundary cooperation in river basins.

Water dependence for an independent country

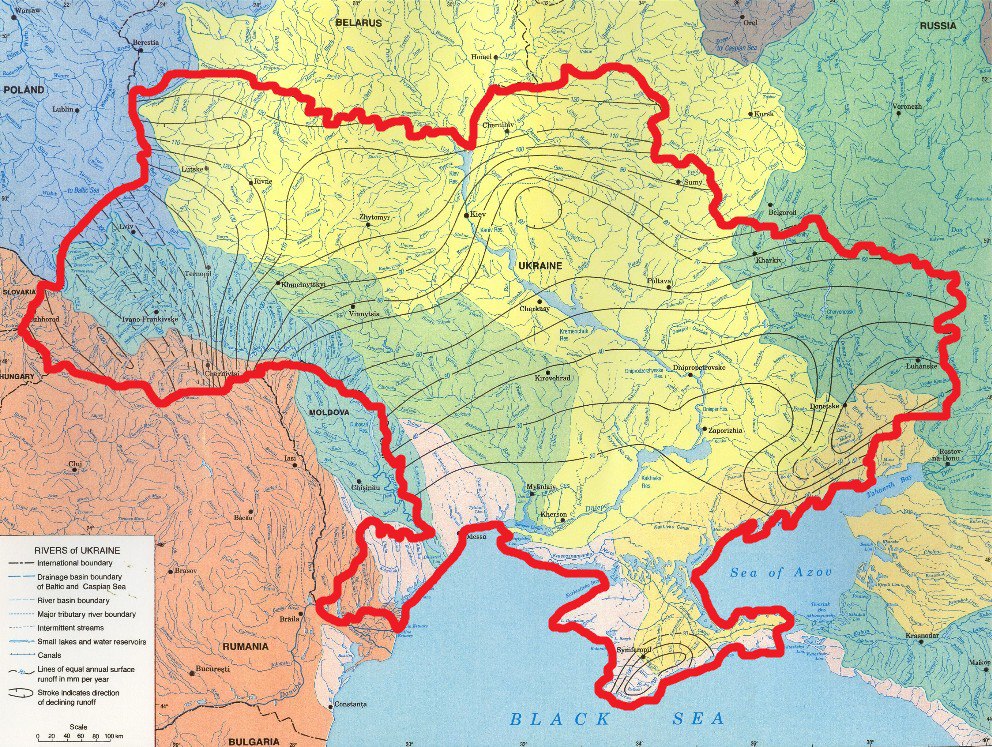

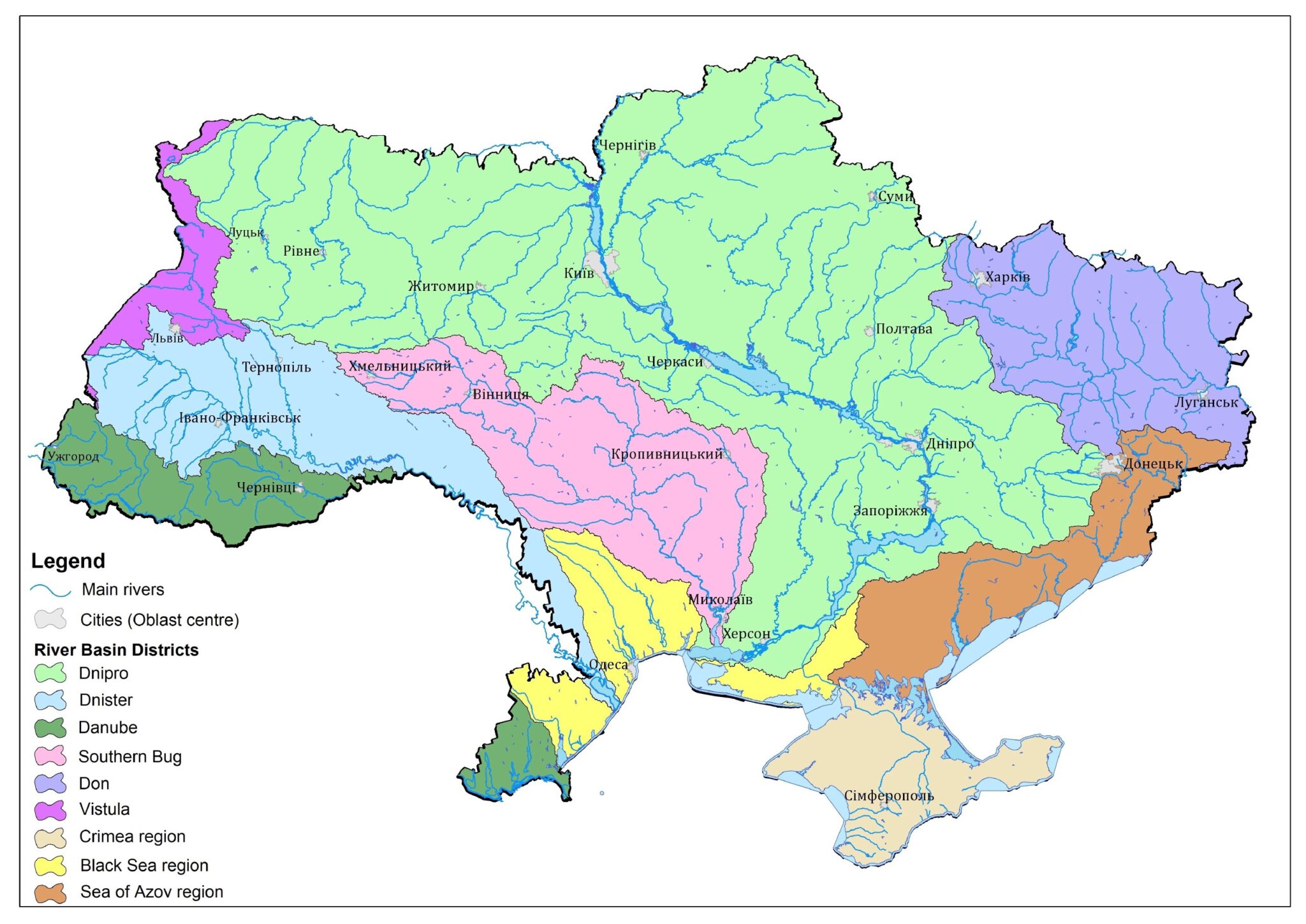

Among European states, Ukraine has some of the most limited water resources; local river flow accounts for just 25-30% of the total. This means that 70% of the country’s water comes from its neighbors. The irony here is that the majority of water resources that Ukraine uses comes from aggressor countries Russia and Belarus (through the Dnieper and Siversky Donets Rivers). Water also comes from Romania and 15 other European nations via the Danube, from Moldova via the Dniester, and other small waterways from other European nations.

Since location is fixed, in 1991 newly independent Ukraine had no option but to cooperate with Russia on the question of river basin management. After the Russia-Ukraine “Agreement on the Joint Use and Protection of Transboundary Water Bodies” was signed in 1992, the two nations succeeded in jointly preventing flooding in the Don River basin in Russia as well as preventing downstream water pollution in the Siversky Donets River following an accident at a sewage treatment plant in Kharkiv.

Although cooperation has stalled since 2014, it is clear that Ukraine is not only dependent on its northeastern neighbor in water terms, but that Russia depends on Ukraine as well. The Siversky Donets River, currently a line in the war’s front, is the largest tributary to Russia’s Don River and flows entirely within Ukraine, although some of its headwaters are on Russian territory. During the war, Russia has openly published its plans for managing the Siversky Donets in the context of integrating the self-proclaimed republics of Donbas with Russia.

After the war’s end, it is quite likely that Russia will be forced not only to deal with these self-proclaimed republics, but also with Ukraine, a nation that is now playing by the European Union’s (EU) international laws, laws that are much stricter than those in Ukraine itself. It would be foolish for Ukraine to fail to resume international cooperation. Water supplies for three-quarters of Ukraine’s population (in the Dnieper and Siversky Donets basins) directly depend on implementation of Ukrainian-Russian and Ukrainian-Belarusian agreements, and the same goes for water quality in the Black and especially Azov Seas.

Transboundary water cooperation

Between 1992-2001, Ukraine entered into bilateral intergovernmental water management agreements relating to border waters with all of its neighbors. These agreements are somewhat similar given that they are all built on the 1992 “Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes.” That convention’s aim is to shift the focus of cooperation from local pollution and individual ecosystem components to an integrated approach to water resources management. In addition to that convention, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and other nations signed a “Protocol on Water and Health.” Its signatories are committed to ensuring water quality safety and access to water for communities and individuals.

In recent years, transboundary water cooperation between Ukraine and EU nations has been accelerating, in part because, as a country-candidate for entering the EU, Ukraine is obligated to implement the “EU Water Framework Directive.” Russia and Belarus, on the other hand, have largely discontinued joint endeavors in this arena. Activities within the directive’s framework are not related to Ukrainian-Belarusian or Ukrainian-Russian relations. Belarus and Russia have no plans to join the EU and thus its directives are not mandatory for them.

Russian troops’ occupation of parts of Ukraine’s territory increases threats to transboundary rivers. Indeed, the temporary blockade of ports on the Dnieper River and the Black and Azov Seas is already forcing Ukraine to actively develop shipping on the Danube River. To achieve this the government is signing agreements with neighboring states and changing laws to facilitate construction of new river ports. However, the Danube delta is one of the most important natural areas in Central Europe and an international biosphere reserve. In current conditions, negative anthropogenic impacts on the delta have the potential to become the most intensive impacts in the entire history of Danube shipping.

Bilateral agreements ratified by both Ukraine and Russia also affect water issues:

Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention)Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers has raised the issue of excluding Russia from the convention. The Cabinet points to the fact that more than half of all Ramsar sites in Ukraine are being used by Russian aggressors to conduct hostilities against the Ukrainian people (as of late spring and early summer 2022). This is largely impacting coastal lands along the Azov and Black Seas and in the Danube and Dnieper lowlands.

Wildlife does not recognize political borders, nor can it comprehend an end to Russia’s responsibility to protect valuable wetland ecosystems. The Ramsar Convention prioritizes international cooperation specifically because protection of migrating fish and birds requires coordinated efforts by multiple countries. Nine Ramsar sites are located in Azov Sea waters and their condition directly depends on fulfillment of both Ukraine’s and Russia’s international obligations.

In the event that Russia and Belarus withdraw from the Ramsar Convention, over ten million hectares of wetlands of international importance (mainly located along the border) could be drained and cultivated. The result would be a painful loss of biodiversity for the entire planet, a colossal release of carbon into the atmosphere, and a climate policy fiasco.

The same transboundary rivers supply cities in both Russia and Ukraine. At the same time, their dependence on water quality is two-sided: waters from the Dnieper flow from Russia to Ukraine, and the Siversky Donets River flows from Ukraine into Russia. Even tacit cooperation on issues of water supply and sanitation is an urgent challenge that must be addressed even in wartime. The Donbas Public Water Utility has continued its work on both sides of the border through eight years of war. Water from Ukraine flows daily via the Siversky Donets-Donbas-Horlivka Canal (temporarily not controlled by Ukraine) for treatment. A certain amount of water remains for the self-declared republics, and a portion is sent back to Ukraine.

Wartime water management

The “Agreement on the Joint Use and Conservation of Transboundary Water Bodies” with Russia was only implemented until 2014. Prior to the war’s start in 2014, the countries exchanged information on a quarterly basis, sometimes even weekly in the event of flooding or reduced water availability.

In 2014, border gauges used for water quality monitoring on rivers flowing between Ukraine and Russia were mostly transferred to Ukraine. Since then, Ukraine has been conducting only unilateral monitoring on rivers in the Dnieper and Siversky Donets basins. With the signing of the “Association Agreement between Ukraine and the European Union” in 2014, Ukraine committed to defining the boundaries of river basins, creating mechanisms for the management of international rivers, lakes, and near-shore waters, and developing plans to manage river basins.

Although the preparation of such documents should include consultations with neighboring countries (if the river basin is not completely within a single country) and be affirmed after negotiations with them – in practice, such interaction with Russia does not occur.

As noted in the Dnieper River Basin Management Plan: “Given the complex political relations between states…” it is once again necessary to act unilaterally. This also occurred when a shared border was delineated that largely coincided with river channels. Contrary to a signed agreement on demarcating the shared border, Russia refused this procedure. As a result, over 20 rivers were unilaterally demarcated by Ukraine.

The surface water monitoring network required in the framework of European integration should also be developed in cooperation with river basin neighbors. This is the only means of ensuring a negotiated and comprehensive overview of the environmental and chemical state of waters in the basin and a classification of surface waters as required in the Water Framework Directive.

Belarus’ activity (more accurately, inactivity) presents an even greater transboundary threat to Ukraine’s water resources. The Berezina River is polluted in Belarus before flowing into Ukraine. Immediately after a pulp and paper mill built to Chinese specifications in Svietlahorsk was commissioned, residents of Jakimava Slabada and the city of Svietlahorsk began complaining of significant health impacts and an unbearable stench.

While the extent of those discharges into the river shocked Ukrainian and international media, Belarusian authorities were unmoved; they had already failed to act for eight years. Ukraine appealed to the Belarusian government for an explanation but did not receive a response. It’s not surprising, of course, since the toxic emissions into the Berezina become a Ukrainian problem just a few dozen kilometers downstream from Svietlahorsk.

Every fifth liter of water in the Dnieper comes from the Berezina River. Moreover, the Dnieper, one of Europe’s largest rivers, provides water to two-thirds of Ukraine: 30 million people, 50 large cities and industrial centers, approximately 10,000 enterprises, 2,200 rural settlements, over 1,000 public utilities, 50 large irrigation systems, and four nuclear power plants.

The pollution of transboundary waters shortly before the border with Ukraine and a refusal to participate in a joint assessment of those impacts are a violation of the “Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes” and the “Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment.” The pollution also contaminates a number of areas included in the EU’s Emerald Network in both Belarus and Ukraine.

Russia’s “deserved” exclusion from environmental agreements

It is inarguable that Russia is violating international environmental law during the course of this war. This is the chief argument used to justify suspension of Russia’s engagement with environmental treaties. In addition, Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers believes that this indicates disrespect not only for Ukraine, but also for all member countries of international environmental agreements and mechanisms. Without interaction between the two countries, the “Agreement on the Joint Use and Protection of Transboundary Waters” has essentially ceased to function. There can be no discussion of joint water management or water protection measures when one of the parties fails to recognize the sovereignty of the other.

Most readers are well aware of the story of Mariupol, the defense of which city stretched for three months and which, ultimately, experienced significant destruction and remains under occupation. The destruction of its sewage treatment system resulted in sewage flooding city streets. Residents used that water for laundry and cleaning because the city’s water supply was also completely disrupted. This is a clear example of Russia’s extreme violation of humanitarian law and a direct consequence of its violation of its environmental obligations.

Specifically, Russia is in violation of the Protocol on Water and Health, which includes a guarantee for protection of human populations from water-related diseases. It is not currently possible to analyze water quality in occupied lands, but there are very alarming signals.

Russia’s exclusion from international environmental agreements would indeed be a significant gesture for the international community. This fate may also await Belarus due to its unclear position.

Risks of exclusion: without obligation there can be no violation

Another side of excluding Russia (and possibly Belarus) from international environmental cooperation mechanisms is the losses that will result for Ukraine and the world. It is reasonable to anticipate announcements along the lines of those that followed Russia’s exit from the Council of Europe and assume that Moscow will no longer comply with any international environmental agreements.

As it stands today, any environmental, human rights organization, or ordinary Ukrainian citizen can pose the question of Russia’s non-compliance with its obligations. In depriving Russia or Belarus of its membership in international environmental organizations, the civilized world is essentially offering a pardon to these two countries. Put simply, without external obligations, a state has no obligations and thus cannot be found in violation.

Ukraine has never been closer to Europe than during this war. This means that future inter-governmental relations must be developed according to European standards. These standards are based on unconditional international cooperation in joint projects, monitoring, basin management, and more. Lastly, if Russia and Belarus express a desire for meaningful collaboration with Ukraine, then their legal basis will be preserved.

In the near future, reparations payments will be critical for Ukraine. Every one of Russia’s failures that violates international agreements offers potential replenishment of Ukraine’s coffers and future investment in post-war reconstruction. Excluding Russia and Belarus from these agreements is equivalent to awarding them impunity, eliminating their responsibility, and reducing the likelihood of reparations being ordered by international courts.

Ukraine awaits future accession to the European Union. At that time, transboundary cooperation will become indispensable. To date, Ukraine adheres to a correct position – no termination of the 1992 Agreement for Joint Use and Conservation of Transboundary Waters. In deciding to take that step, maintaining water quality in rivers after the war will become a Sisyphean effort: one pollutes the water channel, another restores it, and so on in a circle.

It is clear that after Ukraine’s control over all its territories is restored, cooperation with its northeastern neighbors on the subject of transboundary waters will be inevitable. Otherwise, all of their problems “flow” across the border and become a disaster for Ukraine.

Main image credit: Wikipedia

Comment on “War-torn river basins?”