by Sofia Sadogurska

Translated by Alastair Gill

Russia has been waging war on Ukraine for more than nine years, almost 18 months in the form of a full-scale invasion. The war is having a significant effect on the environment, and in particular on the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. The blockading of ports and mining of waters has made them almost inaccessible not only for fishermen or tourists, but also for scientists, who had studied the changes in the marine ecosystems for decades. But, despite the impossibility of taking samples from the sea right now, available data and facts give us an understanding of the impact military activity and occupation is having upon the marine environment. This article is an overview of what we currently know about the effects of Russia’s war against Ukraine on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

War begins – 2014 and occupation

The Black Sea and Sea of Azov have several unique characteristics, in particular their low salinity and isolation, making them natural treasures with rich biodiversity and rare biotopes.

Throughout the 20th century these seas faced numerous problems as a result of the powerful influence of human activity: overfishing, pollution from ports and rivers, the intrusion of invasive (i.e. non-local) species. The situation has been exacerbated by the increasingly powerful influence of climate change, which has led to the disappearance of some species and changes to local ecosystems.

And although Ukraine’s seas were in a state of ecological crisis, in recent years researchers have also seen positive signs, indicating the gradual recovery of some ecosystems as the consequence of a reduction in the level of organic pollution, or eutrophication.

For example, in the northwest part of the Black Sea scientists have observed a trend toward the recovery of sea floor vegetation – groups of Cystoseira and Phyllophora macroalgae. On the whole, scientists characterize eutrophication patterns in the northwest part of the Black Sea over the last two decades as a “sustained de-eutrophication trend”, underlining the recovery processes of the ecosystems under observation.

The war that began in 2014 threw the recovery of Ukraine’s seas into jeopardy and led to the deterioration of marine ecosystems, primarily in the areas that came under occupation: Crimea and the Azov coast in the Donetsk region.

The Sea of Azov first suffered from the impact of military action back in 2014-2015, when half of the Meotida National Park came under occupation. The park contains protected steppe sectors, as well as the sandy Azov spits, including the unique Kryva Kosa, where rare bird species such as Dalmatian pelicans and terns had previously nested. The country’s largest colony of black-headed gulls, which are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine, was also found there. After taking control of the spit in 2015, the Russians made a show of conducting military exercises on it and used the area for military and economic purposes, which led to a sharp reduction in rare bird species. It is likely that some species have disappeared completely, but as long as the occupation continues, it is impossible to assess the situation.

In the Black Sea, the first potential cases of the harmful impact of military activity were also recorded back in 2014. For instance, almost immediately after the beginning of the occupation, Russian forces blew up and sank four ships at the entrance to Lake Donuzlav, closing off access to the sea for Ukrainian vessels. Already then Ukraine’s Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources expressed its concern over the environmental consequences of such thoughtless actions, since the largest of the sunken ships, the submarine chaser Ochakov, lay on the seabed for quite some time and was raised only half a year later.

Following the seizure of these territories, marine ecosystems have systematically experienced negative impacts throughout the period of occupation, particularly as a result of infrastructure construction, extraction of building materials, conducting military exercises, and changes in the status of protected natural areas.

The most vivid example is the Crimean Bridge. Not only were the unique ecosystems and lake on Tuzla Island destroyed as a result of the bridge’s construction, but the migration routes of fish and cetaceans in the Kerch Strait were also cut off.

Fig 3. Tuzla Island in the Kerch Strait. On the left are the lakes and natural ecosystems essentially destroyed after construction of the bridge. On the right is the Crimean Bridge, which was built right across the island (Source: ecoaction.org.ua)

The protected Bakalska spit, which is located in the Black Sea’s Karkinitsky Bay, was also severely affected. Here sand was industrially extracted during the occupation, resulting in the destruction of the central part of the spit and a negative impact on the natural habitats located here, which are formed by coastal salt lakes. Analysis of satellite photographs has shown that by 2019 the spit had already turned into an island, and may vanish completely in the future as a result.

Read this UWEC Work Group article to learn more:

In another part of the Crimean Peninsula, the Russian occupiers turned Opuksky Nature Reserve into a military training ground, destroying formerly protected marine and coastal ecosystems as well as areas of virgin steppeland.

A number of large-scale military exercises have been held around the capes of Chauda and Opuk, including drills to practice the destruction of naval targets using air missiles, thermobaric bombs, and other weapons. This could have had a catastrophic impact on the marine environment as a consequence of chemical pollution, as well as the effect of blast waves.

Read more about the impact of the invasion on Crimea’s environment in this article:

The first consequences of full-scale war – mass dolphin deaths

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, the negative impact on the seas has increased significantly. From the very first days, it became clear that fighting, missile attacks on coastal cities, blockading of ports, and pollution of sea waters with oil and other substances have long-term consequences for the marine environment.

In the spring of 2022, Russian warships were a constant presence in the northwestern Black Sea as they blockaded Ukraine’s ports. Apart from the direct military threat (and these ships were used to shell Ukrainian cities), this situation contained hidden dangers. The discharge of ballast water by warships is not monitored, and both pollutants and potentially invasive species from other sea basins can also enter the marine environment this way.

Then another disaster unfolded: cetaceans began dying en masse. The bodies of dolphins and porpoises started washing up for the first time in large numbers on Turkish beaches near the Bosphorus at the very beginning of the full-scale war, almost immediately after Russian warships entered the Black Sea. The largest numbers of bodies were found on Black Sea beaches during May-June 2022, when the region witnessed the most intense fighting, including on Snake Island.

From January to October 2022, experts from Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece recorded around 1,000 cases of dead Black Sea cetaceans, two-three times greater than in 2019-2021. And since these figures only concern cases when the death of cetaceans was officially documented, the real number may be many times greater.

Also extraordinarily high was the number of cases in which sea creatures washed up alive on the shore. In Ukraine most of these cases occur in Crimea, particularly in Sevastopol, where several Russian military bases are located.

In response to the deaths of large numbers of dolphins in the Black Sea, potentially as a result of Russian armed aggression, the Odesa regional prosecutor’s office has opened a criminal case into ecocide. Scientists have taken a large number of samples in order to determine whether the animals show signs of acoustic trauma. The acoustic effect of the action of warship and submarine radars poses the greatest threat to dolphins, because cetaceans perceive sounds at the same frequencies at which radars operate. This damages the cetaceans’ hearing apparatus and can affect their echolocation – and consequently, their ability to navigate, hunt, and communicate. Underwater explosions, which can cause both acoustic injuries and direct injuries from explosions, represent an additional threat.

And although in 2023 dolphin mortality was lower (which may be due to a decrease in the intensity of fighting in the northwestern Black Sea after the liberation of Snake Island), dead porpoises and dolphins continue to be found on its shores. Scientists say that the deaths of a dozen dolphins near Cyprus in March 2023 were caused by acoustic trauma, which they could have received as a result of military drills by Russian warships, so the threat remains active.

Read about how military hostilities in the Black Sea have caused mass dolphin deaths in this article by the UWEC Work Group:

Pollution

Russian warships create problems not only by moving around the sea, launching missiles, or using radar. Sunken military hardware also poses another threat – fuel spills that create an impenetrable film on the surface of the sea, preventing the passage of oxygen. In addition, spills are toxic to marine life, especially to neuston, microscopic organisms that live in the thin surface film of the sea. This surface layer of water plays the role of an “incubator” for many young aquatic organisms. Its destruction can lead to significant changes in food chains and disruption of the entire balance in ecosystems.

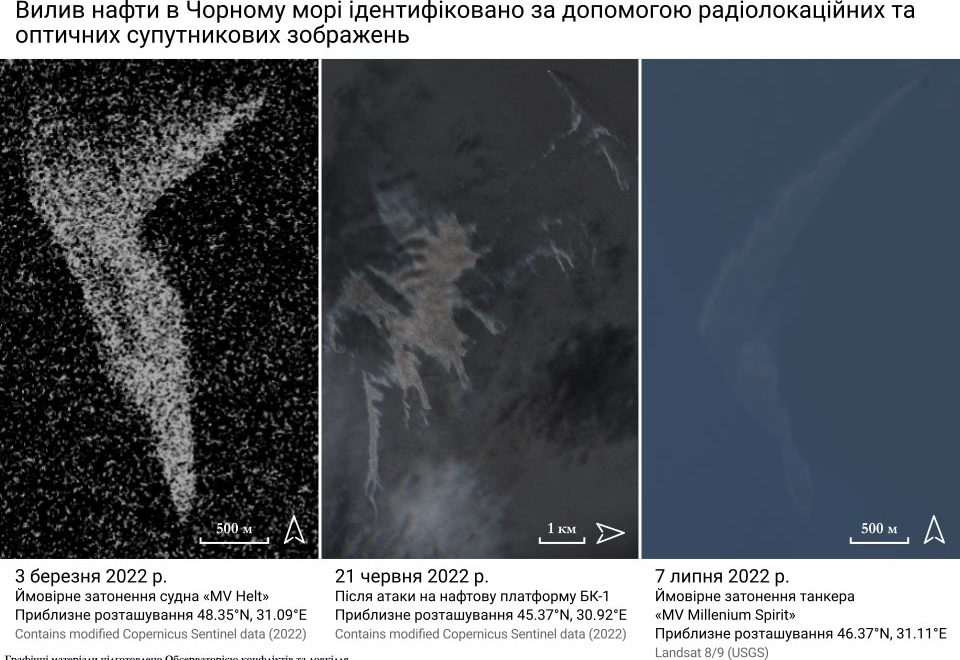

Oil spills are clearly visible in satellite photographs, which show that the film of oil formed as a result of the sinking of vessels has covered tens of thousands of square kilometers of protected marine waters in Ukraine, including the Snake Island National Zoological Reserve, the Zernov Phyllophora Field National Botanical Reserve, and the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, among others.

Fig 6. Oil spills captured by radar and optical satellite images in a study by CEOBS (Conflict and Environment Observatory) and the Zoï Environment Network (Source: CEOBS)

Unfortunately, this is not the only problem. The Russian army is attacking coastal cities, infrastructure, and ports. The coastal zone contains oil depots, warehouses, waste landfills, factories, and treatment facilities, which, when damaged, pollute the water with chemical compounds.

For example, several ships, an aluminum refinery, storage tanks for fuel, caustic soda, and warehouses where ammonium nitrate was probably stored were damaged as a result of repeated attacks on the port of Mykolaiv, near the mouth of the Bug River estuary. In addition, the leak into the sea of 1,000 metric tons of sunflower oil from reservoirs destroyed by a Russian drone attack in October 2022 caused an environmental catastrophe.

The oil has polymerized in the sea water, causing mass bird deaths. The discharge of sewage from the Galitsinovska treatment plant, documented in satellite images, may also have had a negative effect on the ecological state of the estuary. Untreated wastewater can result in chemical compounds (drugs, fertilizers, household chemicals) entering the estuary’s ecosystems, causing an increase in the level of eutrophication and, as a result, algal blooms.

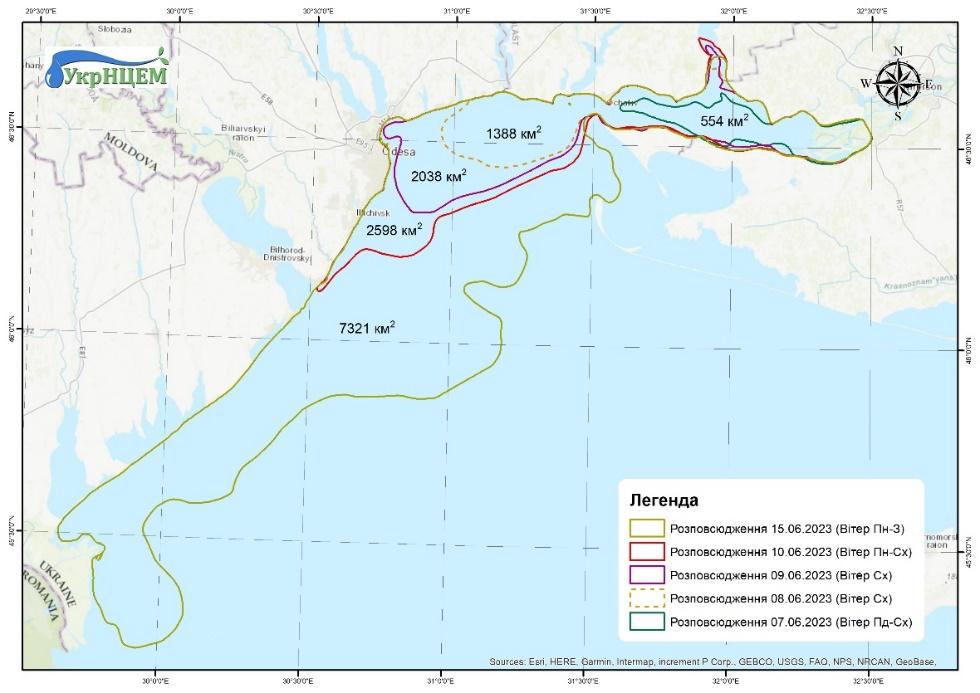

The destruction by Russian forces of the Kakhovka Dam in June 2023 was a catastrophe for this region and the whole of southern Ukraine. Several protected areas were in the flood zone. The existence of certain species and ecosystems was jeopardized, and vast volumes of freshwater entered the Black Sea, polluted with fuels, lubricants, fertilizers, and wastewater from flooded settlements and fields.

Within the first few days of the dam’s destruction, a rapid desalination of sea water and a drop in salinity from 14 to 4 ppm were recorded off the coast of Odesa, leading to the death of some hydrobionts in shallow waters. In some coastal sectors scientists documented acute toxicity in the sea water, with an ultra-high nitrogen concentration at certain times, which may indicate direct pollution from sewage. The sudden arrival of a large number of organic and mineral substances in the marine ecosystem triggered the mass development of phytoplankton and, as a result, led to water bloom, which at its peak covered more than 70% of the northwestern part of the Black Sea.

According to satellite data, after the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam polluted river waters were borne a great distance by currents and even reached the Danube River, covering more than 7,300 km2 of the Black Sea in total.

Read about the environmental consequences of the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in this article by the UWEC Work Group:

Nature destroyed: the impact on protected areas

There are a large number of nature conservation sites in Ukraine’s coastal waters: nature reserves, national nature parks and Emerald Network preserves. Avian migration routes cross the region, the coast is home to rare endemic animal and plant species, and the waters teem with marine life. These areas have suffered as a result of oil pollution, the sinking of ships, military occupation, and some of them have felt the direct impact of military action.

Warships not only pollute the environment, but can pose a threat even when they end up on the bottom of the sea after being sunk. The Russian cruiser Moskva sank in the northwest part of the Black Sea, where several protected areas and rare biotopes are located.

The area is home to the Zernov Phyllophora Botanical Reserve, created to protect a colony of the red alga Phyllophora. This ecosystem is sometimes compared to the Sargasso Sea, which is also an accumulation of loose macroscopic algae, but this Ukrainian “sea” of algae is located on the seabed, making it unique in the world. A large number of rare species are found here, including those included in the Red Book of Ukraine. One can only imagine the damage a sunken cruiser could cause to these vulnerable ecosystems. Scientists have said it will be necessary to study the site of the wreck and the substances contained in its weaponry to understand whether there were radioactive elements present, how much fuel was on board, and whether bottom biocenoses were harmed.

In nature everything is connected, so the destruction of coastal colonies can also affect the situation in marine ecosystems.

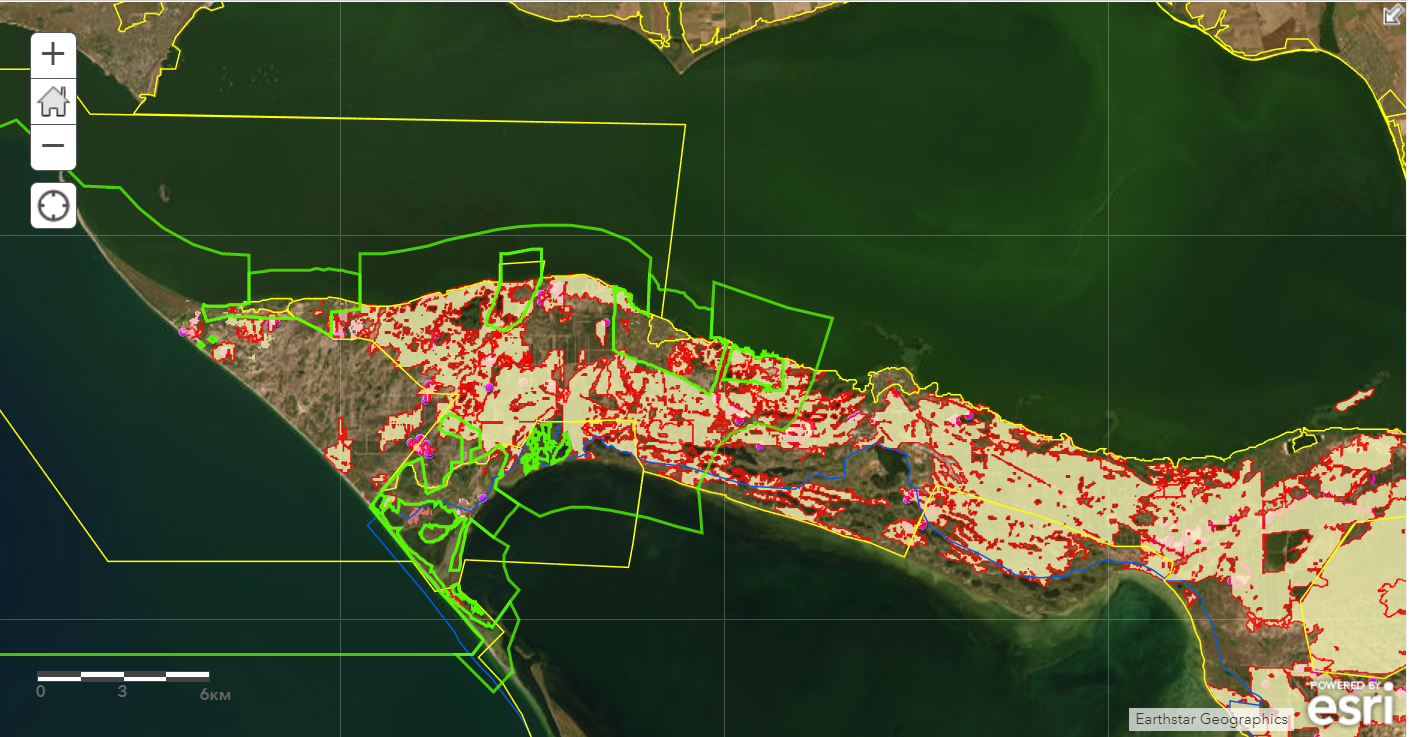

Fires have inflicted irretrievable damage on the protected Kinburn Spit, where various marine and coastal colonies are under protection. Fires in 2022, caused by exploding arms, shelling, and other factors, were the most extensive for decades. A total of 131 fires were recorded on the Kinburn peninsula in the first year of Russia’s full-scale invasion, devastating more than 5,000 hectares of the park. The nesting places of about 100 species of birds were destroyed by fire, and the steppe and coastal areas were affected as well, which could even lead to extinction of endemic species.

The Dnieper floodplains, located in the lower reaches of the Dnieper River before it enters the Dnieper-Bug estuary and the Black Sea, have also suffered from military activity and shelling from Russian armed forces.

According to park staff, analysis of satellite data shows that over 5,000 hectares of the Lower Dnieper National Park were destroyed as a result of fires in 2022. Frequent fires in the floodplains caused by shelling cause irreparable harm to the environment and have resulted in the loss of a large number of animals and plants in the park. This national park is one of those that has suffered most from the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam by the Russians in June 2023.

Another national park that has suffered as a result of the Russian invasion is Dzharylhach. In spring 2023 Ukraine’s Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources reported that occupying forces had backfilled the narrow strait near Lazurne separating the island from the mainland. According to the ministry, this was done in order to use the protected island for military purposes.

This strait is extremely important for water exchange between the shallow Dzharylhats’ka Gulf and the open sea, the waters of which saturate the bay with oxygen. Blocking the strait may lead to the silting up and degradation of the ecosystem of the entire Dzharylhats’ka Gulf, a waterbody which contains rare seaweed and seagrass ecosystems. This bay is home to the highest density of porpoises, as well as unique coastal groups of common dolphins and bottlenose dolphins. The degradation of the ecosystem threatens the existence of the bay’s cetaceans.

Is there hope for the recovery of the Black and Azov seas?

To understand how to restore the seas, it is important that experts know the consequences and scale of the impact of war upon marine ecosystems. The Sea of Azov is currently inaccessible due to the military occupation, and it is impossible for now to assess this impact. In the Black Sea experts are extremely limited in their ability to take samples in coastal waters and in estuaries. But initial observations say – that there is hope.

Due to the mining of coastal waters, the beaches in the northwestern Black Sea are closed to tourists, meaning a reduction in anthropogenic load – that is, pressure on ecosystems as a result of human activity.

The Black Sea has essentially become the subject of a sad but unique experiment, in which we can see the local effect of the absence of fishing, a large number of commercial vessels and tourist load upon marine and coastal ecosystems.

For example, on beaches in Odesa scientists have observed the mollusk Donacilla cornea, which in recent decades has become extremely rare not only in Ukraine, but along the whole of the Black Sea coast. This species, which lives in the sand along the tidal line, has become extremely common on many of Odesa’s beaches in the last year due to the lack of large numbers of tourists. Favorable weather conditions (low water levels in the rivers, relatively low temperatures) have also led to a recorded local improvement in the environmental condition of the sea – at least, in the vicinity of the Gulf of Odesa.

At the same time, such changes, unfortunately, may be short-lived. With the return of tourists and large numbers of ships, in unfavorable climatic conditions, and also given all the negative consequences of the impact of the war, the situation in general may be rather difficult.

At this stage it is already clear that the recovery of the sea will require, first of all, detailed studies of the consequences of the war with the involvement of a wide range of experts. Once victory is secured, it will be necessary to record all sites where ships were sunk, all sources of pollution, and all damaged ecosystems. It will be important to determine which sectors have suffered particularly badly, which sectors have remained relatively untouched, and which new zones of water, coastal areas, and wetlands will need to be added to the network of protected areas in order to help nature to recover.Severely affected areas will require the development of recovery strategies and the creation of management plans for these sites, as well as special measures for the restoration of ecosystems. Examples could include creation of artificial reefs, introduction of representatives of species captured in adjacent unharmed areas, elimination of invasive species, or the use of other techniques already being used to restore degraded marine ecosystems.

Main image credit: EPA-EFE/SERGEI ILNITSKY

Comment on “Impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov”