Oleksiy Vasyliuk

Translated by Jennifer Castner

One of the most widespread consequences of military impacts on natural landscapes is the construction of fortifications. We have already written that the consequences of the construction of walls and fences along state borders (1, 2, 3) creates serious restrictions on the movement of land-based animals and results in high mortality and disrupted life cycles. However, much greater environmental damage is caused by trenches and bunkers, the construction of which has grown to enormous proportions as the Russian war in Ukraine gradually becomes trench warfare. This article will discuss the impact of underground shelters on the environment: trenches, bunkers, and other fortifications.

UWEC authors and editors understand the logic of Ukraine’s top leadership including President Volodymyr Zelenskyy himself in strengthening Ukraine’s defense line. Ultimately, stopping aggression against Ukraine is the only means to ending this environmental destruction. As with any other consequences of this war, international law states that the construction of defensive structures by Ukrainian troops is a forced measure and any consequences are solely the fault of the aggressor. We hope that after hostilities end this article will help Ukraine to assess the consequences of building fortifications and develop a rational plan for the rehabilitation of damaged territories.

Russian fortifications have significantly changed Ukraine’s landscape

While a range of defensive fortifications have been built in Ukraine over the past two years, we are primarily discussing trenches and other underground shelters (bunkers) used by the Russian army.

There are several reasons for this approach. An analysis is necessary to assess the consequences of Russia’s unauthorized engineering activities within Ukraine that result in deterioration of Ukraine’s environment. There is no publicly-available statistical or cartographic information about fortifications on the Ukrainian side of the front. Satellite data analysis shows that the volume of Russian fortifications significantly exceeds Ukraine’s.

Russia’s lengthy preparations to attack Ukraine included detailed plans to construct fortifications requiring the use of a large amount of equipment and specialized army engineering units. Over almost two years of war, changes to the frontline have occurred in such a way that mostly areas without fortifications have been liberated from temporary occupation. The area currently temporarily occupied by the Russians is saturated with the most significant line of fortifications ever built on Ukrainian territory. In addition, large-scale minefields surrounding areas damaged by construction of trenches may remain in place for many decades after the war is over.

Use of open source data to study fortifications

Open source intelligence (OSINT) analysts collaborating with DeepState, a Ukraine-based project to map and document military operations during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in real-time, were the first to prepare a quantitative assessment of Russian fortifications in Ukraine.

According to data released by DeepState, over 6,000 kilometers of fortifications were documented on the Russian side of the front line as of the end of 2023, information about which is publicly available on their website.

After analyzing satellite images, OSINT analysts calculated the surface area of Russian military fortifications in Ukraine and divided them by type.

The most fortified regions are in Zaporizhzhya Oblast – 1,869 km (length of fortification within the region) and in Donetsk Oblast – 1,865 km, where the largest number of military clashes have been concentrated for over six months. Luhansk Oblast also has fortifications stretching 1,140 km. 886 km of fortifications were identified in Kherson Oblast, mainly along the Dnieper River and stretching from Novaya Kakhovka to Heroysky. Russian troops have also hardened approaches to the Crimean Isthmus. In Crimea itself “just” 265 km of fortifications have been dug.

Trench construction has partially damaged 46 protected areas, including Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve and Azov National Park.

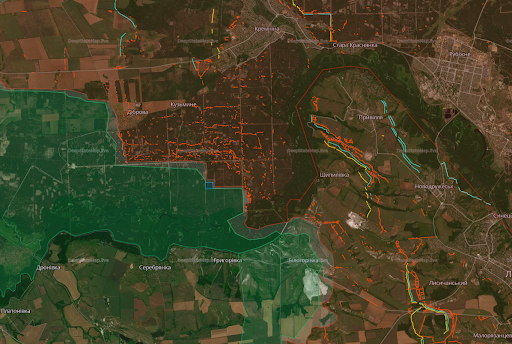

Fig 1-2. Examples of the scale of the Russian army’s fortifications (red indicates occupied territories, green – liberated, other areas were not occupied). Source: DeepState.

Many fortifications were planned remotely and lacked detailed information of the terrain. As a result, some trenches are currently flooded with water and not usable without drainage. Additionally, the entire defense line built by the Russian Armed Forces along the left bank of the Dnieper was completely destroyed when the Kakhovka hydropower plant’s dam was blown up on 6 June 2023.

It is also important to note that the Russian army seeks to conceal some fortifications entirely underground. If it weren’t for the dynamic analysis carried out by DeepState specialists, we might assume that they were simply backfilled; by fall grass had already grown there.

What does fortification building mean for the environment and climate?

Along with munitions explosions, fires, and heavy equipment maneuvers, construction of fortifications is one of the largest factors negatively impacting landscapes. For soils, military installation of fortifications is arguably second in consequences after munitions explosions. In more than a few locations they co-occur, further exacerbating environmental consequences.

The construction of fortifications does not share the chemical impacts of munitions explosions, generally causing only engineered landscape changes. Despite that, they are accompanied by other negative environmental consequences, for example, waste pollution and violation of public health guidelines.

At the same time, the construction of fortifications is significant and often destructive for flora and fauna. In combination, vegetation destruction, disruption of topsoil, disturbing the hydrological balance of groundwater, reduction of natural humidity, and desertification have the most tangible impacts for wildlife. Missing from this list is chemical pollution, but that pollution is usually more important in economic and human land use terms and less consequential for wildlife.

During construction of defensive structures both above and underground (dugouts, trenches, bunkers, tunnels, storage facilities for fuel and lubricants and materiel), soil layers are mixed and soil structure is destroyed. These factors are the main drivers of soil erosion and destruction.

The thin fertile layer of topsoil breaks down, revealing the undersoil and scattering it across the surrounding area. Winds, precipitation, and temperature changes further scatter soil layers (sand, loess, etc.). Vegetation is consequently suppressed over a large area, and upper soils are buried beneath overlying rock and lower soils. From a soil formation perspective, this can readily be described as desertification. In current conditions, these negative factors are further intensified by more frequent drought and other extreme events caused by global climate change.

When constructing fortifications, groundwater level is not always considered. As a result, some fortifications disrupt the hydrological regime and cause water to rise to the surface, waterlogging areas and raising soil salinity.

Deep saline aquifer water can also be brought to the surface and spread beyond the immediate boundaries of defensive structures.

Lastly, all fortifications inevitably attract concentrated artillery attacks.

All of these factors disturb soil processes over much larger areas, where, among other changes, landslides, inundation, and soil subsidence can occur. The zone of influence of a single trench, ditch, or bunker ranges from 20 to 100 meters or more. Assuming such estimates, then areas with disturbed or destroyed soils experiencing active erosive processes caused by the construction of Russian trenches can range from 800 to 1,000 sq. km.

That amount is comparable in size to the drained former bed of Kakhovka Reservoir and is easily visible even at the scale of a world map.

Another threat identified during 2022 expeditions to liberated Kamianska Sich National Park in Kherson Oblast was the use of rare plant vegetation by Russian soldiers to camouflage combat positions. We believe that this does not represent deliberate destruction of rare species, but rather Russian soldiers cutting turf containing several types of feather grass and other steppe plants to camouflage bunkers. The national park was specifically created to protect such species.

Bunkers: cemeteries for large trees

The majority of bunkers built for long-term use are reinforced by tree trunks, resulting in the consumption of a large amount of high-value lumber. They are usually built using the trunks of Common Pine and other pine species, valued for having the straightest trunks and few branches.

Dugout walls are lined with these trunks, and the top is covered with a triple-layer roof, also made from trunks. It is thought that such a structure can withstand a hit by a 152-155 mm caliber projectile. 20-50 tree trunks are required to build a fortified bunker for 5-10 people.

Endless changes in the front line and shelling damage means that there is a constant need to build more and more new fortifications.

All pine forests within the territory temporarily occupied by Russian troops are artificial plantations and small in area. Given the changing climate, it will probably no longer be possible to rapidly grow new coniferous forests here. As a result, construction of fortifications using timber on the Russian side of the front essentially constitutes the direct destruction of the last (admittedly artificial) forests in Ukraine’s steppe zone, forests with tremendous environmental significance.

Almost all such forests are located within nature refuges, national parks, and other protected areas, and some of them have existed for more than 100-120 years. This applies, in particular, to Beloberezhye Svyatoslava, Sviati Hori, and Siversky Donetsk National Parks, Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, and at least 50 other nature refuges. In other words, any logging in such forests is unacceptable.

In addition to using trees for construction, life in bunkers also demands a constant supply of firewood for heating and cooking, creating additional pressure on the ecosystem.

As for the Ukrainian military, fortification building by law uses only legally-harvested wood obtained with permission in Ukrainian forests where forest restoration is not complicated by climatic conditions. Ukraine has even introduced a special procedure for the supply of wood for defensive purposes.

Although “selective” logging occurs more often, it is not any better for nature

Smooth pine trunks are used for engineering bunker structures. This means that only the most suitable trees are logged for building fortifications – a form of selective logging.

Such analysis is supported by the fact that to date we have been unable to find evidence of large-scale clear-cutting. There are a few known exceptions in the Oleshkovsky Forestry Enterprise in Kherson Oblast (foreign media mistakenly assumed this to be proof of Ukraine-sourced timber exports to Russia, and the Ukrainian media subsequently widely reprinted their foreign colleagues’ error).

Although most of this logging is selective, it is nevertheless not good news for pine plantations in Ukraine’s steppe zone. Pines have shallow root systems and such forests persist only thanks to dense canopies that conserve moisture and maintain cool temperatures. Logging individual trees exposes the roots of other trees to the sun’s rays, quickly drying soil and causing further aridity in those forests. In the coming years, we can anticipate large-scale aridity in pine plantations damaged by logging and munitions explosions.

Other dangers to forests along the front line

There are also conflicting issues for trees growing in areas with trenches and bunkers.

First, forests and shelterbelts are used as natural camouflage for combat positions. For the trees, this means that their exact location will inevitably become an active conflict zone, including munitions attacks. Frontline videos show that most trees in these areas have no remaining branches.

Secondly, all such concealed positions are located below ground level and thus offer poor visibility. Troops often specifically destroy such trees (and particularly shelter belts) in order to ensure a better view around their positions.

Ecological footprint of life in the trenches

Another problem worth mentioning is pollution resulting from construction and daily life in defensive structures.

Troops living for months in fortified areas dump all the products of their daily lives in the immediate vicinity of bunkers and trenches: garbage, feces, and possibly even communal graves.

As soldiers retreat and advance, they leave their trash and waste behind. In those conditions life-supporting items (ranging from food to bedding) are delivered by support units and are most often single-use.

All packaging, including that of ammunition used in combat in incredibly large quantities, is also single-use.

Damaged trenches and bunkers, along with remaining everyday items, are damaged by rain and snow and are abandoned when the front line is redrawn.

As a result, each soldier leaves behind a significantly larger environmental footprint than the average person living in their own home where there is less excess to be consumed and all types of waste can be disposed of or recycled.

In addition, the presence of a large number of remains of dead soldiers creates high risks for bacteriological contamination.

Since 2015 (not long after Russia began to seize Ukrainian territory), experts have repeatedly noted the likelihood of groundwater contamination resulting from ill-conceived, spontaneous burials. This factor also significantly affects prospects for post-war land use of areas where the most active hostilities occurred.

Wildlife in trenches

Small terrestrial animals suffer the most from the construction of fortifications, be it insects and other flightless arthropods or vertebrate species of reptiles, amphibians, and mammals.

Trenches become a trap for most animals with the misfortune to fall into them. In theory, animals could climb out on their own. But when soldiers are present in the trenches, rapid death is the outcome for many animals.

Imagine, for example, a situation where a snake or rodent – often feared by many people – falls into a trench. Soldiers would rather kill such an animal than carefully catch and release it. Moreover, during active hostilities there may not be opportunity for a humane approach.

For many species of animals, this threat is becoming quite urgent, as fortifications stretch for over 800 kilometers across the entire front line in both eastern and southern Ukraine.

As for animal migration, the line of defensive fortifications is unlikely to have a significant impact; in this part of our planet, land animals do not undertake significant seasonal migrations. That said, local wildlife movements including dispersal of sub-adults, predator movements in search of prey and, most importantly, animals fleeing from explosions, gunshots, and other events lead to numerous cases of animals landing in trenches and ditches.

Animals entrapped by military fortifications include many rare species of endemic mammals, such as Nordmann’s Mouse, Feather-tailed Three-toed Jerboas, and the Sandy Mole Rat. UWEC Work Group previously discussed the consequences for wildlife from the Kakhovka Reservoir flood. These species live precisely where the Russian troops’ defense line was built along the left bank of the Dnieper.

For reptiles, the vast majority of all species of snakes and lizards living in the combat zone and in temporarily occupied territories are listed in the Red Book and are actually endemics of this zone within Ukraine.

Today many stories can be found on the internet telling of both soldiers rescuing animals from trenches and brutal animal killings and cases of incredible sadism.

Lastly when fortifications lacking well-thought-out drainage flood with groundwater, the chances of saving wildlife are further reduced.

Land rehabilitation and restoration

After war ends, removing fortifications will be one of the most difficult tasks in Ukraine’s green recovery. As we mentioned above, the areas experiencing active soil erosion are much larger than the fortifications themselves. Any approach to restoration must be comprehensive.

How should areas damaged by fortifications be rehabilitated? Of course the artificial changes in the relief of such areas should be smoothed by backfilling trenches. The exact methods for such work should be decided upon only after the end of the war, when the full extent and breadth of soil damage will be finally clear. Soil science tells us, however, that restoring the relief alone will not stop soil erosion.

Restoring protection forests damaged by the wholesale placement of fortifications within them will be the most urgent component of Ukraine’s future green recovery. Essentially the vast majority of protection forests in the country’s most arid landscapes have been destroyed or damaged during Russia’s full-scale invasion. That level of destruction has resulted in active desertification processes. The loss of each forest belt accelerates wind erosion and desertification processes across hundreds of hectares, and the cumulative effects of these losses significantly accelerate desertification throughout the region.

The first 18 months of the full-scale war have set Ukraine back in implementation of its “National Plan to Combat Desertification” by a decade. It is not known whether it will be possible to restore lost protection forests in current climatic conditions.

Nature does not wait for wars to end. As with the former Kakhovka Reservoir – now covered in young willows and other vegetation – vegetation regrowth starts very quickly. Study of satellite imagery reveals that in spring and summer this year almost the entire frontline became a greenway. Vegetation is rapidly taking over areas where no agricultural cultivation is occurring and no pesticides are used.

Unfortunately, unlike the bottom of the Kakhovka Reservoir, abandoned fields and destroyed settlements are initially largely overgrown by alien invasive species. Despite their success in occupied territory, invasive species do not create or support stable plant communities, although such vegetation may be useful when it comes to combating wind-induced soil degradation. Generally speaking, however, invasive plant growth means a loss of biodiversity.

It is important to begin studying which plant communities are growing in places with abandoned fortifications. Different types of fortifications in different landscapes create different geomorphological conditions (microrelief, moisture regime, substrate), subsequently partially colonized by vegetation. In most cases these “colonizers” will be invasive species. Examining these areas facilitates prioritization of restoration efforts, including support for self-restoration.

The first action for Ukraine’s green recovery in frontline areas should be mine clearance. Soon thereafter reclamation must begin. Recovery includes:

- Identification of minimally-contaminated areas that can eventually return to economic use;

- Immediate restoration of perennial grass ecosystems in all damaged areas experiencing soil erosion. Only these ecosystems are capable of quickly healing pockets of erosion and stopping the loss of soil moisture; and

- Restoration of shelterbelts, removal of invasive plants, phytoremediation.

Knowing the scale of munitions use, it may turn out that some areas that experienced fortification could become nature restoration zones in the future – economic “no-go” zones. However, these areas should not simply be left to their own devices “for self-restoration”, but rather require human intervention to restore ecosystem stability as quickly as possible. Rehabilitating former fortification zones reduces climate impacts and prevents desertification of the entire southeastern region of Ukraine.

Main image credit: NBCnews

Comment on “Military fortifications in Ukraine – what comes next?”