Oleksiy Vasyliuk

UWEC Work Group previously examined the environmental impacts of minefields and munitions contamination for Ukraine. Military action spreads explosive objects over very large areas on land and at sea. The issue covers the entire temporarily-occupied zone, the line of combat, all formerly occupied territories, and the international border zone. According to various estimates, 26-33% of Ukraine’s territory will require demining, work which could require anywhere from 77 to 750 years.

Some sites can be cleared relatively easily, returning the land to economic use. At the same time, the areas most damaged by military activity, the international border zone, and the largest minefields will probably require a very long time to be cleared. The amount of time for which some areas in Ukraine will remain mined is, in fact, so great that it may require multiple human generations to clear them. What will happen to the areas slated to wait the longest for demining? UWEC Work Group examines that question in this article.

Tranquil life for wildlife amidst deadly mines

It is worth noting that the initial process of laying mines in itself does not have a significant impact on biodiversity. Generally, only large animals can be physically harmed by triggering a mine’s detonation. Instances of large animals killed due to contact with mines and tripwires have been made public more than once. Deaths of Red Book-listed species in Ukraine have also been documented, in particular moose and Przewalski’s horses.

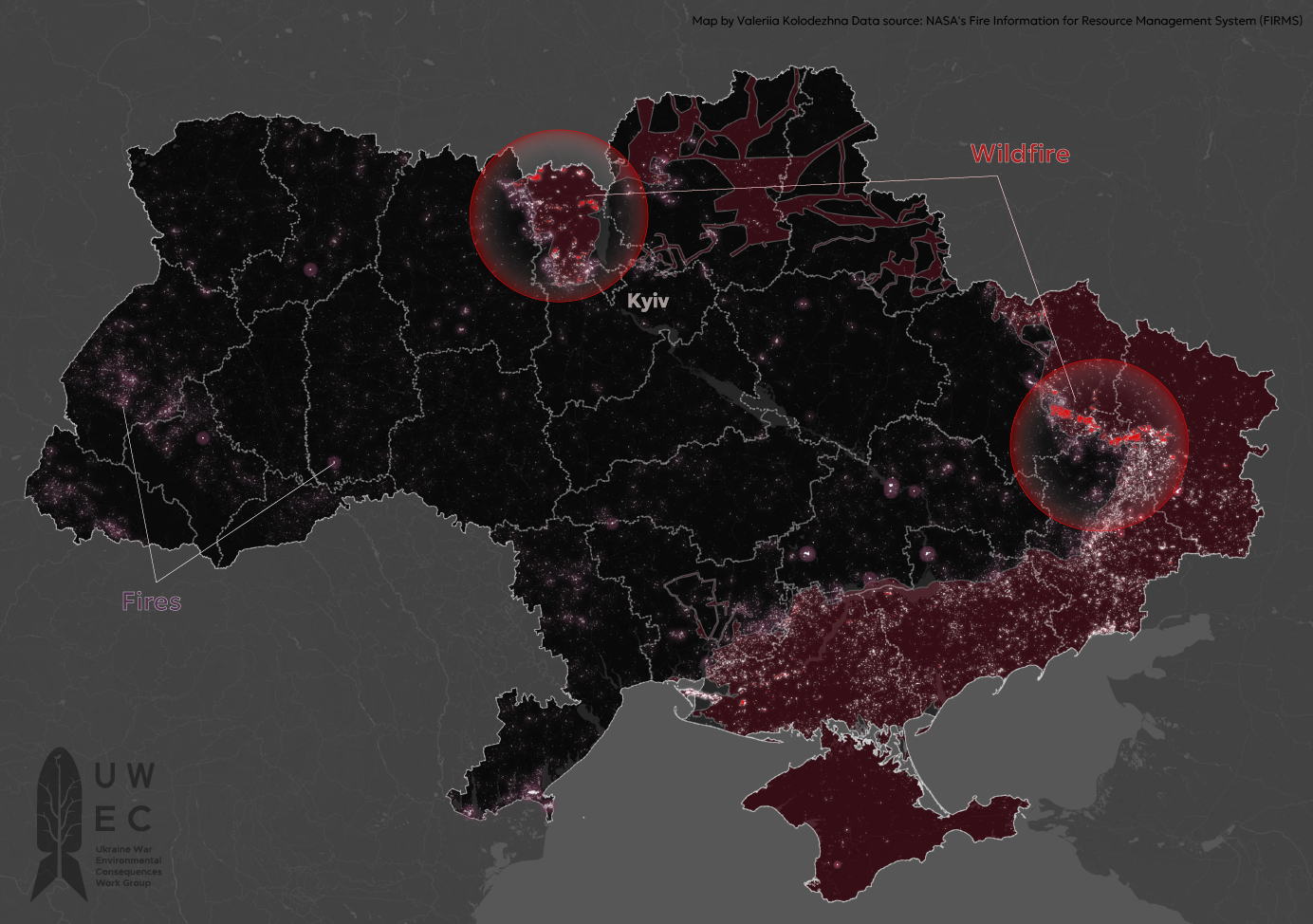

Future population losses among large mammal species as a result of explosions seem inevitable. That said, the relative absence of other threats in mined areas may have a positive effect on the restoration of wildlife populations. Small fauna, birds, flora and mushrooms do not experience any changes at all as a result of mine-laying. Moreover, economic activity ends in mined areas, further reducing negative pressure on wildlife. The exception is spontaneous fires that humans cannot extinguish in mined areas, causing new large-scale losses of biodiversity.

Looking at the experience of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant Exclusion Zone, today the location of the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve and a place where people have limited access due to the threat of radiation, one can be sure that mined landscapes could benefit many wild species. The simple fact that humans will not interfere with the presence of wild animals in large areas, frighten birds during nesting season, hunt, or use deadly chemicals to combat “forest pests” is a guarantee that the number of species and their populations in such areas will grow.

Invasive species and the emergence of new ecosystems

A completely different picture emerges on the site of pre-war settlements and fields. Here, there is rapid regrowth of vegetation followed by the reappearance of wildlife. One should not, however, rush to label such areas “wilderness”. Beginning in 2023, studies of satellite images of Ukraine revealed an enormous greenbelt stretching along the entire front line. It is so large as to be visible by satellite on the European scale.

This greenbelt consists of plants growing in the active combat zone, as well as in mined areas. Such mass overgrowth can be seen especially well along the entire southern front: from the city of Enerhodar and further to the east. Estimates are that this area of spontaneous overgrowth already exceeds one million hectares in size.

The absence of economic activity and the generalized destruction of most mined areas as a result of military actions lead to the wide-scale spread of invasive species—both herbaceous plants and trees. For many of these species, their large seed base causes mass overgrowth even in the first months after humans depart the landscape, be it in settlements destroyed by war or abandoned, damaged or occupied fields.

The initial degradation of vegetation resulting from intensive agricultural use also facilitates the spread of invasive species. Large-scale prior use of herbicides, a low percentage of preserved natural ecosystems able to contribute to biological diversity, and new chemical pollution resulting from military combat result in lands that are not habitable for many species and that become a convenient environment for the spread of aggressive invasive species.

Read more: Invasive species threat resulting from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine

Nature reserves, lost amidst the ruins

Some of the mined and temporarily-inaccessible sites possess a designated conservation status. They include nature reserves, national nature parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and internationally protected sites, including UNESCO biosphere reserves. Under conditions of total inaccessibility caused by mining and occupation, conservation areas lose their special conservation status and are left to spontaneously recover after military action and earlier long-term economic use. The scale of this disaster recovery zone is so large that conservation areas will appear as small “islands” in the post-war landscape.

Will these areas become more valuable in a biodiversity development context after the war, as was the case of the Chornobyl exclusion zone, where radiation-contaminated areas became important natural areas that were later given the status of a biosphere reserve? Or, conversely, will they degrade in the near future due to the impossibility of preventing the spread of invasive species? These territories have the potential to become invaluable depositories of biodiversity, serving as a sort of cornucopia from which wildlife could rapidly spread to areas under restoration. The opposite scenario is also possible: the last remnants of wild nature will simply be overwhelmed by invasive plant species. For now, we cannot know what the changes will be.

Can demining be accomplished without further environmental harm?

A new challenge for Ukraine’s natural areas will be demining, a process usually carried out using explosive mechanical methods that involve the detonation of all unexploded ordnance. Although such work usually does not harm people, it nevertheless has a wide range of environmental consequences associated with the explosions. At its foundation, demining work damages ecosystems and maximizes environmental pollution. Ordnance detonation is even often carried out in rivers and lakes, undoubtedly destroying many living organisms.

Are there alternatives to demining? Although private landowners, communities (hromadi), businesses and the state as a whole will strive to quickly return land to economic use, another option is to declare mined territories as nature conservation areas where spontaneous restoration processes will continue. This applies to lands that cannot be demined in the near future or where demining is not demonstrably expedient. For example, it is unlikely that mines will be removed along Ukraine’s international border. However, the question can be posed more broadly. Should lands so damaged by military action that their further economic use is ruled out be demined?

Are there alternatives to demining? Although private landowners, communities (hromadi), businesses and the state as a whole will strive to quickly return land to economic use, another option is to declare mined territories as nature conservation areas where spontaneous restoration processes will continue. This applies to lands that cannot be demined in the near future or where demining is not demonstrably expedient. For example, it is unlikely that mines will be removed along Ukraine’s international border. However, the question can be posed more broadly. Should lands so damaged by military action that their further economic use is ruled out be demined?

UWEC Work Group has previously explored the consequences of building border zone infrastructure and the potential for including border zones in nature conservation areas. These types of land management can serve as a source of ecosystem services, including, for example, carbon sequestration.

Read more:

- Beasts and Barriers: Obstacles along international borders and their impact on land-based vertebrates

- Protected areas and border zones in Ukraine: How to harmonize them?

Approaches in other countries: Is it better to skip demining?

Other nations, including Bosnia, France, Germany, and Cambodia, have opted to remove lands from economic circulation or to establish exclusion zones in areas contaminated or mined during military operations. In some cases, for example in natural forests, demining is only possible when accompanied by the forest’s total destruction by fire. It is clear that destroying a forest for the sole purpose of demining is not always advisable, as examples from the Berlin area show.

Since 1989, approximately 1.5 million hectares of military lands have been excluded from human use in Europe after the end of the Cold War. Use of very large areas was often not realistic as a result of chemical pollution and mining, one reason for converting military training grounds into nature conservation areas. For example, Denmark proposed that 45% of its training grounds be included in the Natura 2000 network, the Netherlands 50%, and Belgium 70%. In European Union countries, training ground lands are predominantly government-owned (for example, Germany owns 492,000 hectares, of which 316,000 hectares are part of Natura 2000).

In the United States, lands polluted by man-made military development belong to the Department of Defense (4 million hectares), of which 15% have been declared national parks and protected areas.

Ukraine has its own experience, not only the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, but also some military lands that previously served as military proving grounds and now have nature conservation status. The best example is Oleshky Sands National Nature Park, previously used as a bombing range. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainian environmentalists repeatedly proposed the establishment of large nature conservation areas on other military lands, including proposals for national parks: Tarutynskyy Steppe (Odessa region), Samara Forest (Dnipropetrovsk region), Velikiy Les (Sumy region), Divichki (Kiev region), and Kytsivska Desert (Kharkiv region).

In addition to those environmental considerations, economic factors are also in play. Spending money on demining areas that cannot be used for economic purposes is impractical. Restoration through phytoremediation or other cleaning methods may be too costly to be implemented.

Read more about phytoremediation: Seeds of metal: How war is polluting Ukraine’s farmland and threatening food security

Planning for reclamation and restoration of biodiversity in post-conflict areas remains a topic for further study. No European country has had experience in rehabilitating such a large area of war-affected land.

In addition, no nation has ever undertaken demining such a huge area as will be required in Ukraine. Calculating that demining will require at least a century, then the feasibility of anti-mine activities must be considered not only for heavily contaminated areas, but also in connection with those that have simply been awaiting demining for a long time. It can be assumed that in just a few decades, the areas last in line for demining will become overgrown with dense forests. So, a hundred years down the road, demining will likely require that vast century-old forests will need to be burned. Naturally, such a plan would face questions, including consideration of their environmental feasibility.

How to begin the demining process

After reaching initial broad conclusions on this issue, the demining process should prioritize clearing the lands most likely to be returned to economic circulation. For example, mechanized demining of nature conservation areas would be a disaster, the consequences of which are no less terrible for natural ecosystems than deep plowing for agricultural use.

It is quite likely that after conducting objective assessments of the future potential of the most war-damaged areas and opportunities for demining, areas in Ukraine that have suffered most from military action would be divided into those worth demining and those best left as exclusion zones. This could result in greater diversity in the country’s landscapes, filling Ukraine with important ecosystems, and even potentially improving living conditions in demined areas.

The stewardship paradigm for land resources in Ukraine must change and attitudes of Ukrainians toward ecosystem services be evaluated in order to undertake fundamental government decisions on the importance of preserving biodiversity.

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Main image source: Guardian