Viktoria Hubareva

On a visit to the eastern shore of the former Kakhovka Reservoir in Zaporizhzhia Region, UWEC staff writer Viktoria Hubareva found out how life has changed for local communities (hromady), who have been deprived of access to water for over a year now. A lack of drinking water, slow-burning peat fires and collapsing businesses are all contributing to a sense of desperation, coloring local attitudes to preserving the “green sea” that has appeared on the bed of the reservoir and the tough decisions that await.

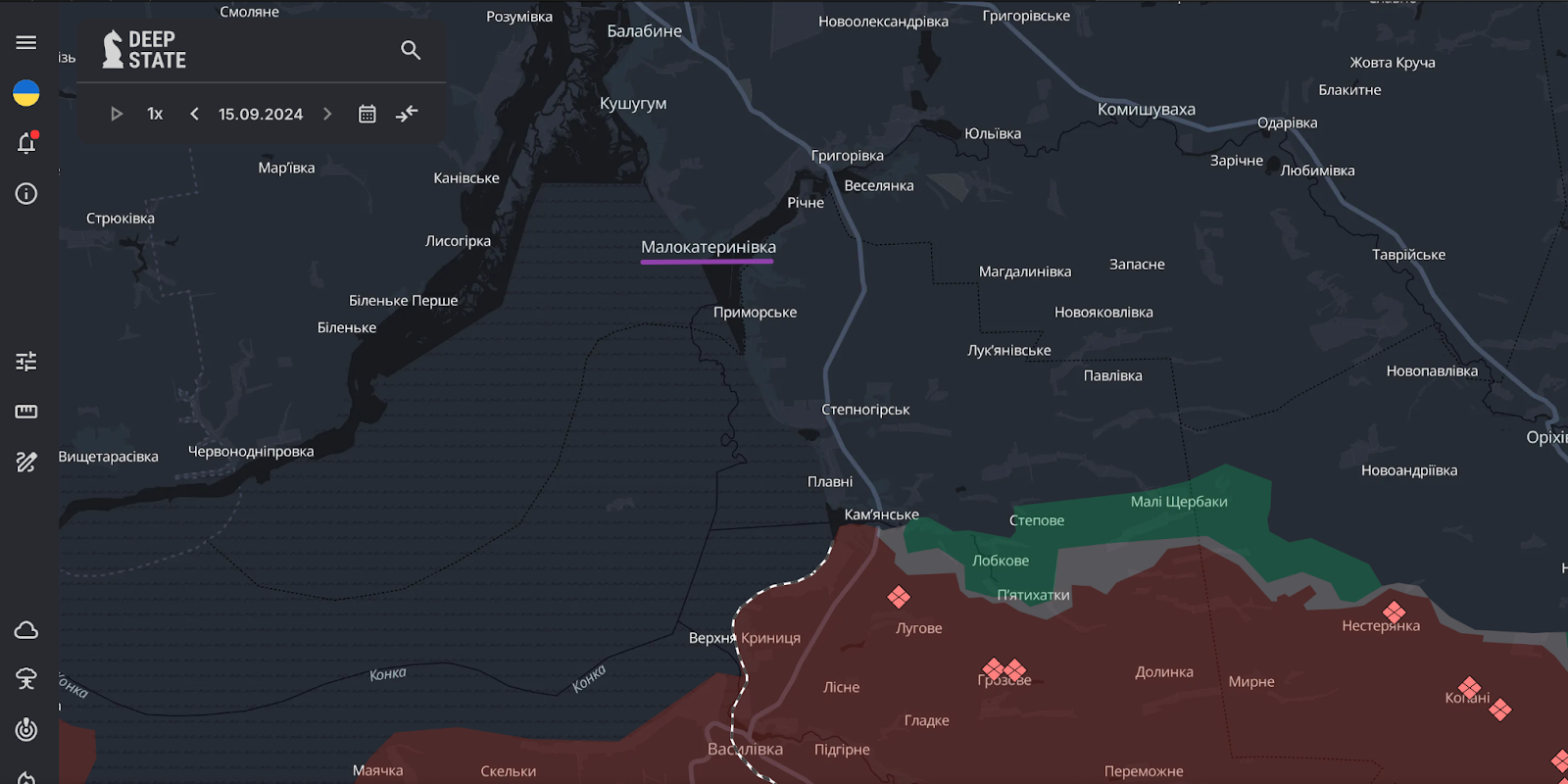

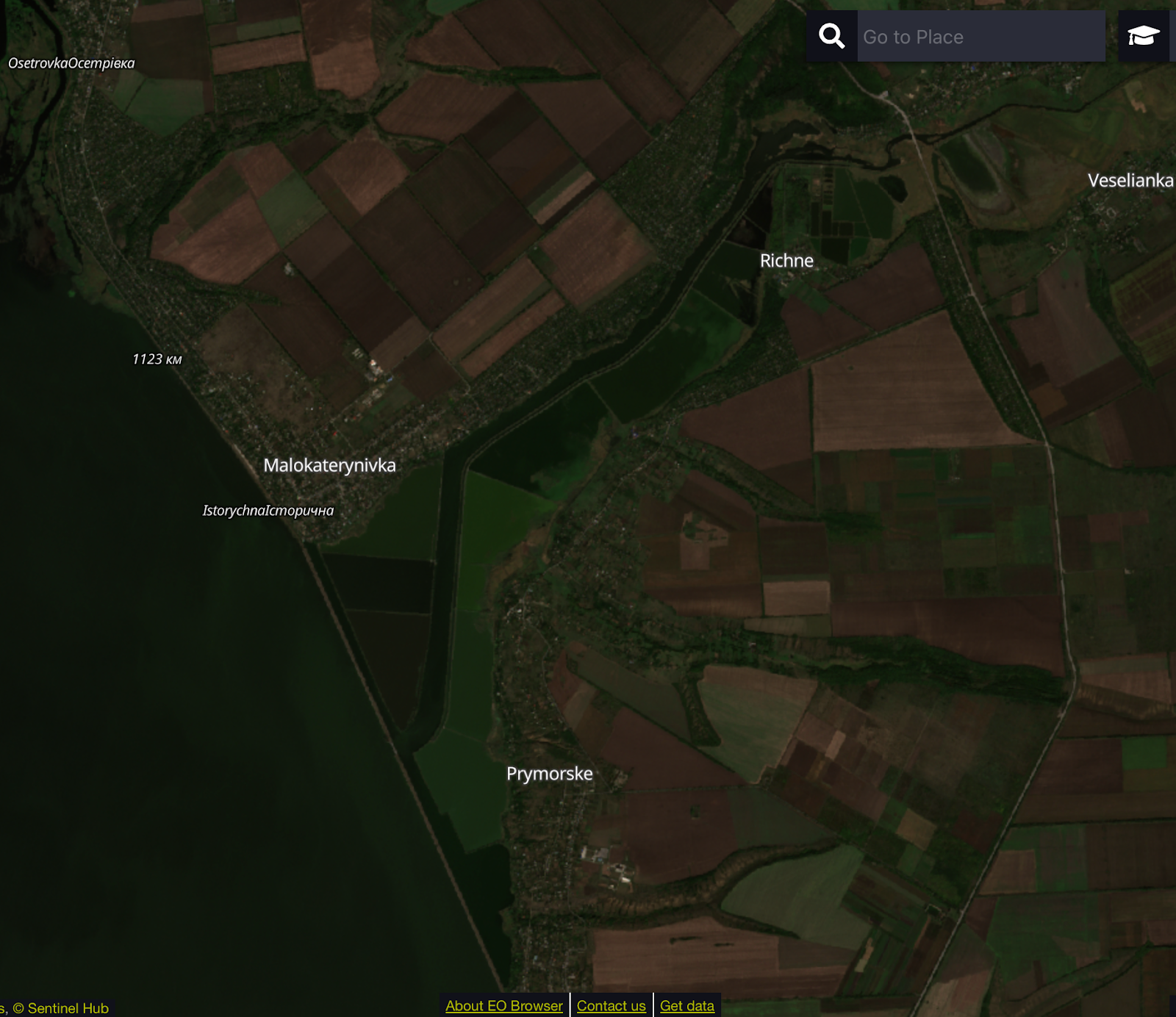

We are standing on a high bank. Beneath us, the wind moves in waves across a sea of green leaves that stretches almost to the horizon. This is the former Kakhovka Reservoir, which completely dried up after the destruction of the dam by Russian forces in 2023 and is now covered with millions of young willow saplings. In the distance, on the reservoir’s far shore, currently occupied by the Russian army, is visible. Here and there, gray smoke rises, marking places where shells have exploded. The sound of artillery fire is almost continuously audible from afar.

This is the view from the village of Malokaterynivka in Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Region. Before the loss of the reservoir, Malokaterynivka thrived. It was home to a fish farm, residents grew vegetables in greenhouses for sale, and the area was popular with summertime vacationers, when they came here to spend time in the dacha cooperatives located along the reservoir. Since the loss of the reservoir, life for the community has changed completely. Business has dried up, Ukrainian tourists no longer come here for their summer vacations (including because of the war) and local residents are suffering from a lack of water.

The local community is in favor of restoring the reservoir, but this is an unlikely prospect. In an interview with UWEC, Volodymyr Sosunovsky, a local resident and chairman of the Kushuhum village council, talked about how they are coping with the situation, what solutions they see and what action can be taken.

Not a drop to drink all summer

Water was always a valuable resource for the local population, but there had been no problems with it since the 1970s. An 18-kilometer pipe with a diameter of 1 meter, built between 1967 and 1975, initially provided enough water for local state farms. Water was supplied from Zaporizhzhia to the settlements of Balabyne and Kushuhum, and further to Malokaterynivka. From the 1990s onward, people began to actively pipe water to their individual homes from the centralized water supply, which eventually led to shortages. Water continued to flow from Zaporizhzhia but was no longer enough for all needs.

Eventually, a solution was found: water piped from Zaporizhzhia was used as drinking water, and a pumping station was installed for technical needs. Water was also taken from the Konka River using pumps. The pumping station worked around the clock, replenishing large metal tanks with a capacity of 240-280 cubic meters each. This met the needs of the population, particularly when it came to watering vegetables. The system worked smoothly for many years until Russian forces blew up the dam of the Kakhovka Reservoir. The Konka dried up, leaving nowhere else to obtain water.

At present, only Balabyne has running water. Kushuhum is partly supplied. A water tank has improved the situation, but five and a half streets in the village have been without water since the beginning of summer. Malokaterynivka has been without water for a second year now, since the water supply simply does not reach the settlement (probably due to weak water pressure).

The large metal cisterns now stand empty. The one on the shore is riddled with holes from shelling.

Life is hard and so is the water

Deliveries of water are now organized with the help of the State Emergency Service and the regional water utility company (oblvodokanal). Every day, 20 cubic meters of water are delivered (though at the peak of the heatwave in July, this rose to 80 cubic meters). In an attempt to find a way out of the situation, the local population is trying to ensure access to water on their own by boring wells.

“But at a depth of 60-70 meters, the water has a high lime content, and this is a problem,” says Volodymyr Sosunovsky. “It’s possible to solve the problem by using artesian wells, but this is very expensive. The depth of wells where there’s water reaches 103 meters, though analysis shows that it has a high lime content all the same, albeit less critical than at shallower depths. Besides, this kind of solution isn’t an option for everyone. The granite layers that need to be drilled through make the drilling costs very high,” he explains.

Called “hard water,” water with a high lime content leaves scale on the walls of a kettle and has a particular aftertaste. Washing regularly in this kind of water regularly results in dry hair and skin, and if used for drinking water, it can lead to a whole range of different diseases.

Hard water is also unsuitable for watering plants. Although it contains calcium and magnesium, which are used for the “deoxidation” of soil, when these are present in high concentrations, nutrients are unable to dissolve in the water. As a result, plants do not receive adequate nutrition: herbage begins to die, and leaves dry out and fall off. Such plants may not even survive until the flowering period.

In order to use this kind of water, special filters need to be installed, and this means additional costs, which most of the population cannot afford.

All of this has had a huge impact on the established way of life for local residents.

Where is the 5:05 train?

Right beneath the steep slope on which we are standing runs a railway. It has stood idle since the beginning of the full-scale war. Later, when we reach the Malokaterynivka station, we see that saplings are already growing on the steps. The station looks a little surreal, which is no surprise — it has not been used for two and a half years.

“Everyone does what they can to earn a living, and our population raised vegetables in greenhouses. Not small ones, like families use, but big ones, 50 meters long,” explains Volodymyr Sosunovsky. “In this way, local residents earned enough money to feed themselves and their families for a year. In the main this was pensioners. When the railway was operational, almost all of our residents sold vegetables at Zaporizhzhia 1 [Editor’s note — the name of a railway station in the center of the city of Zaporizhzhia]: tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, and so on. Everyone would quietly board the first local train to depart at 5:05 a.m., passing four stops: Malokaterynivka, Osetrivka, the center of Kushuhum, Kushuhum and Balabyne, and then Zaporizhzhia 1. They would arrive, and the city folks would buy up these goods in a few hours,” says Sosunovsky, adding that this went on year in, year out.

The same timetable, the same stations. Until the Kakhovka disaster, when the water disappeared.

Growing something in a greenhouse requires quite a lot of water, since rainwater cannot enter the structure. When there is no water or it is supplied irregularly in insufficient quantities, crop yields decrease.

“Those who were able to adapt invested in wells and water filters,” says Sosunovsky. “In Kushuhum, for example, people have been growing blackberries for over 20 years. They have big 4-hectare fields. It’s a former military base. The military also drilled a 200-meter well there. And it’s very good. And the water there is different, suitable for watering [crops]. That’s how they work.”

As for those who can’t afford either filters or wells, they are now having to abandon this way of making a living. But it is not only those who made their living from vegetables who have lost their jobs.

A body blow for local businesses

From the high bank where we stand, the fish farm is clearly visible. It’s hardly business as usual here: the enterprise is still operational, but the chance of the business surviving until next year is very slim, because water has already disappeared from most of the ponds.

“The water in the ponds was part of a through-flow,” explains Sosunovsky. “It came from the river Konka, which had ponds on both sides, and then entered the reservoir. After the Kakhovka hydropower plant was blown up, the river’s water level fell several meters, and now the channel in the Konka has completely dried up. They tried to maintain the water level in the ponds, close off the straits, and gradually pump in additional water. But the effect was insignificant. Two ponds dried out completely; in the others fish are dying because the water isn’t moving and there’s less and less oxygen. If the situation doesn’t change and the winter is dry, then it’s possible the fish farm will shut down, since the fish might just disappear.”

“It’s logical to assume that in three to four years, willow will appear here,” adds Sosunovsky, referring to the same vegetation that now covers the bed of the former reservoir.

This was just one of several fish farms in Malokaterynivka, and the only one which survived until the end of summer 2024. Other ponds have already lost their water, and even dried out completely.

Local business, which was reliant on tourism, is also disappearing. The region used to be more attractive thanks to its opportunities for beach vacations. It was possible to rent a cottage in the dacha cooperatives, and there were recreational outdoor centers in Malokaterynivka. Now the beaches are gone, and the tourist sector is flagging.

“Our attractiveness for tourists, above all, was the dozens of dacha cooperatives between Kushuhum and Malokaterynivka. People used to come here to relax. You could say that half the city of Zaporizhzhia had their dachas here. They used to come with their families, with their kids. This led to the growth of our region’s economic potential, since people were buying goods in our stores, which in turn brought in tax revenues. Unfortunately, today we see that stores and kiosks are closing. This has an impact on our budget. For example, the number of individual entrepreneurs has fallen from 400 at the beginning of 2021 to 75 today. The situation with tourism is also getting more difficult,” says Sosunovsky.

The fire that burned all summer

The loss of water has affected not only the earnings of local residents, but also the new ecosystems which had successfully taken shape and adapted during the time the reservoir existed. The situation is exacerbated by the proximity of the frontline.

“Look at the smoke over there, in the distance,” says Sosunovsky, pointing to the side. A column of smoke is rising into the sky. “That’s the result of Shaheds [drones]. This used to be our floodplain with islands but now everything’s dried out. The river that flowed out of the Dnieper dried out too. Why did this fire appear? Because everything had turned into peat. When the fire brigade turns up to put it out, they tear up the soil, but the fire continues to smolder at depth. It’s very difficult to put out, so until winter starts or rain falls, the situation won’t change,” he explains.

The floodplain systems that have been created here over the years gradually formed peat bogs. These were not a danger when they were covered with water, but now they have begun to dry out. The fires can go on for months, becoming increasingly active in hot weather. This particular fire has already been burning for two and a half months, i.e. all summer. Extinguishing such fires is almost impossible for two reasons: the areas in question are difficult to access and burning also occurs underground, which is typical of peat fires.

“There used to be a very rich natural complex here with a large number of different animals. During active fires many of them didn’t manage to find refuge. As a result deer, elk, and wild boar perished. Whole families died,” says Sosunovsky.

‘I think about 80% of this willow will dry up’

Despite the fact that the very creation of the Kakhovka Reservoir 70 years ago was an environmental catastrophe involving the forced resettlement of local people and the flooding of historical monuments, over the course of two generations local residents have grown accustomed to the new conditions. Now, when those in green circles are actively discussing the preservation of the “green sea,” Sosunovsky voices the interests of the local community, who back the restoration of the reservoir. “If there was water here, we would be glad of its presence; for us it’s very important,” he says.

As for the “green sea” itself and the potential services it could provide to the ecosystem, Sosunovsky is skeptical and believes that all the trees will gradually die out as a result of drought, which is becoming increasingly more pronounced:

“The willow that has been actively growing here loves water very much, and ideal conditions have developed for it. For example, such a willow can grow as a bush up to three or four meters, but then its growth stops,” he says, relying on his own experience and personal observations of nature in his native region. “Do you see the empty sectors?” he asks, pointing to dark patches amid the green sea where there are no trees. “A year ago, there was still water there. Now they’ve dried out; the only moisture left is a meter down. Next year, probably, there won’t be any moisture, and I think around 80% of this willow will dry out.”

Sosunovsky also supports his position by pointing to the fact that until it was flooded in the mid-20th century the entire surface area of the former Kakhovka Reservoir was steppe. Willow forests, which require plenty of moisture, have never grown here. However, he also recognizes that the silt that accumulated on the bed of the reservoir for so many years has changed the composition of the soil. Sosunovsky believes that the bed of the Kakhovka Reservoir may be fertile and sees this as very promising.

Whether the trees will survive in the future is unclear for the moment. When the Kakhovka disaster occurred, many environmentalists expressed concern that the former reservoir could become the site of an enormous desert. When young shoots began to appear on the ground, they said that they would not survive the winter. Yet a real forest has now begun to form on the site of the reservoir, and it is impossible to predict what this place will look like in another one, two or ten years.

A future without the Kakhovka Reservoir

Whatever final decision the government takes after the de-occupation of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions — to rebuild the reservoir or not — it will take time. When the reservoir was originally filled with water back in the 1950s, the process took more than five years.

So, as Sosunovsky notes, the community needs to find new solutions to restore the region’s economic potential and solve the problems with water supply.

“The water problem remains critical. It’s very difficult to get water from great depths and purify it. So it’s necessary to establish a hydraulic balance to ensure the supply of drinking water. While the situation is still more or less stable for nine months, three months a year without water is critical. Now we’re also faced with new problems, like frequent shelling, which adds uncertainty,” he says.

The management of land formerly under water is another urgent issue. Some of it belongs to the Kushuhum community (which includes Malokaterynivka, Kushuhumб and Balabyne), but these areas also belong to the Ukrainian Water Fund, which means that local communities are unable to use them at their discretion.

When asked how the community would use this land if given the opportunity, Sosunovsky suggests planting a forest. “Perhaps it would be worthwhile to create a coniferous forest covering 200-300 square meters, which could be a great start,” he says. Another option is to attract tourists with new leisure offerings, such as archaeologically themed walks to places where old Cossack cemeteries and settlements were located before the Kakhovka Reservoir appeared. However, as long as the war continues and the front remains so close – it literally runs along the opposite shore at present – it is obviously difficult to make such decisions.

“I believe that the state’s task is to provide serious support. Our mission now is to show international organizations that the situation is critical in order to receive grants and aid. I hope that after our victory and the restoration of peace, legislation will change and allow us to manage these territories more effectively, and we’ll continue to think and work on solutions in this situation,” concludes Sosunovsky.

The UWEC expert view

Many settlements in Ukraine’s frontline areas have found themselves on the threshold of the unknown: their familiar way of life has been destroyed but a new one has yet to be created. It is obvious that the uncertainty caused by the war postpones the solution of problems “until later,” primarily for those who live along the frontline.

Volodymyr Sosunovsky is a good example of an active community representative, someone who is involved in international projects, participates in the development of local recovery plans and actively comments on their “new reality” in the media. And the Kushuhum community finds itself at the center of the international media’s attention, as this is the closest one can get to the front in the south. The best access to the boundless landscapes of the historic Velykyi Luh meadowlands, which are now recovering on the site of the former reservoir, is also found here. In the end, a UWEC journalist also visited this place.

But we do not understand why the community’s water supply from the city of Zaporizhzhia has been cut off in recent months, leaving the part of the south of the Zaporizhzhia Region that is most familiar to international and Ukrainian media without its most critical resource.

Our partners from the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group public organization have prepared a series of appeals to government agencies that should shed some light on the reasons for the deterioration in the quality of life in the Kushuhum community and perhaps find a solution that is consistent with the “Green Deal” and does not involve the restoration of the reservoir.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image: The “green sea” on the site of the former Kakhovka Reservoir. Source: Viktoria Hubareva