“We must apply a ‘gold standard’ to evidence gathering for the numerous environmental crimes perpetrated by the Russian invasion.”

UWEC’s Aleksei Ovchinnikov recently interviewed Olena Kravchenko, executive director and board member of the Ukrainian NGO Environment-People-Law (EPL), also editor-in-chief of the magazine EPL.

International charitable organization Environment-People-Law has existed since 1994. Since then, EPL has become a key group of experts on Ukrainian environmental law. In particular, it was this organization that initiated and participated in the signing of the Aarhus Convention in 1998. EPL founded the first environmental law journal in Ukraine as well as the country’s first institution specializing in environmental law. It has also held numerous online and in-person events. EPL worked with government agencies on the development and modernization of a regulatory framework for environmental protection and the human right to a healthy environment.

Aleksei Ovchinnikov: As far as I know, EPL has been collecting data on environmental crimes since 2014, the start of the war in Ukraine. Can you tell us more about your experience in analyzing the environmental consequences of the war?

Olena Kravchenko: Yes, we started developing methodology and conducting analyses back in 2014-2015. But even then we understood that a large-scale invasion would take place sooner or later. This meant that environmental damage would be catastrophic.

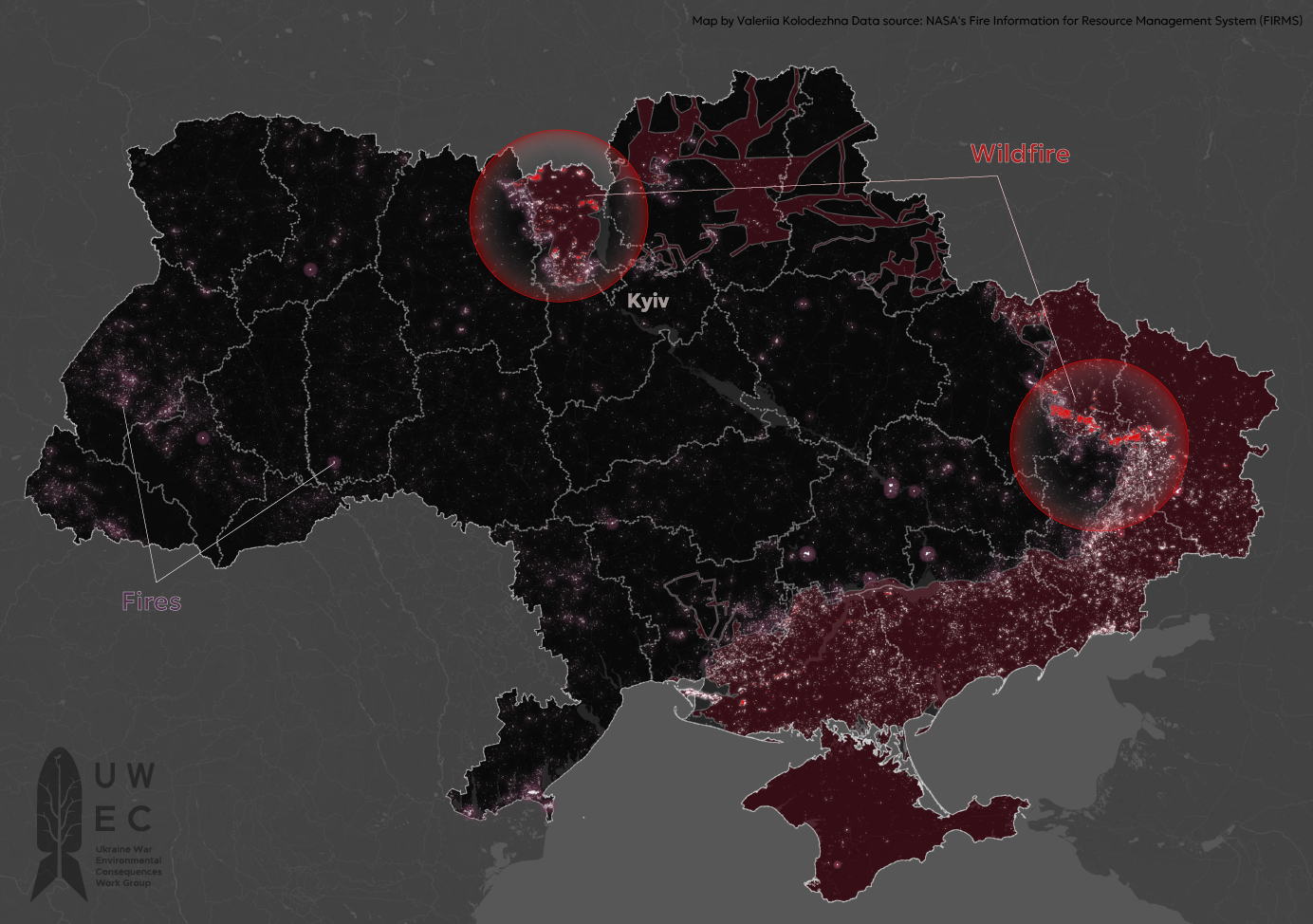

Back in 2014 we developed a methodology for collecting data on environmental crimes stemming from military actions. We developed a clear-cut approach on how to document forest fires, including how to calculate damages, updating a methodology that has been in place since Soviet times. We also developed an approach to cataloging damage caused by the war in nature reserve areas. We developed and formalized a methodology for assessing the impact of war on soil and land resources.

We shared all of these methodologies with the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources – we’ve been working with that Ministry since 2014. Today, we use these tools to analyze the consequences of Russia’s invasion on Ukraine’s environment. In other words, now we have a clear idea of how to quickly and reliably document negative impacts on forests, soils, and conservation areas. Using these methodologies allows us to gather an evidentiary base that can be used when cases go before international courts.

AO: Can you already draw any conclusions based on your analysis of the invasion’s environmental impacts?

OK: It’s obvious that the consequences are catastrophic and that the funding needed to restore the environment will be colossal. I believe that they may exceed the total cost of infrastructure restoration.

We also know that collecting evidence of the impacts should have started on 24 February, the first day of the invasion. Unfortunately, the Ministry, State Environmental Inspection Agency, and public organizations were late to start that work.

Today, five months later, we are already seeing a completely different picture. In some places nature is healing itself. In other places we can no longer document the damage inflicted by the aggressor. Almost six months on, it is much more difficult to document and collect supporting evidence of crimes against the environment than it would have been to do it as soon as these crimes were committed and discovered.

AO: In Ukraine today, many initiatives collect data on crimes against the environment. Efforts include the Office of the Environmental Inspection Agency, the Ecozagroza (‘Environmental Threat’) project under the aegis of the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Ecodia Environmental Action project, and EPL’s work. Do they all act as a single coordinated network, or do they collect information separately?

OK: All of these projects operate in parallel; this is a result of differing approaches to data collection. For example, we cannot be sure that the information collected by Ekozagroza has been verified. Ekozagroza receives information that has not gone through secondary verification. When we ask what is being used to confirm the cataloging algorithm or what type of regulatory document is being used to support the algorithm, Ekozagroza cannot give an answer.

So, the information Ekozagroza is collecting has not been verified and cannot be presented as a thoroughly investigated case within the framework of an international court.

Unfortunately, that kind of unverified information can only make it more difficult to obtain reparations for crimes against the environment. When presented in an international court, this sort of evidence will go up in smoke. It will be rejected by the court, which, of course, creates serious problems for us as environmental lawyers.

AO: So, such evidence does not meet standards for information collection and verification?

OK: Yes, in international practice, a “gold standard” has already been developed for analysis of military crimes against the environment. It was developed by international lawyers who analyzed numerous military conflicts, whether they be in Nicaragua, Iraq, Yemen, or other places.

We are also trying to collect evidence using this gold standard so that potential cases regarding Russian war crimes against Ukraine’s environment can be accepted, considered, and recognized by international courts.

Unfortunately, sometimes we are unable to conduct the necessary analysis because of the very structure of Ukraine’s legal system. For example, the Criminal Procedure Code in Ukraine does not provide for inviting foreign experts to collect and process information. If we had this opportunity, it would greatly simplify standardizing information before transferring it to an international court.

In our organization’s view, in the five months since the active phase of the military invasion began, it should have been possible both to develop regulations and instructions to guide the invitation of foreign specialists to investigate crimes and confirm instructions for collecting and processing information about the war’s environmental impacts using the gold standard. Despite this, legislative change is slow in Ukraine, and of course that complicates our work.

AO: Olena, can you tell us a little more about this ‘gold standard’?

OK: In principle, it is a standard of requirements for assembling evidentiary support. For example, how satellite imagery confirming crimes against the environment should be collected, processed, and presented.

The standard also details requirements for court appearances of witnesses to a given crime who are prepared to testify during a hearing. According to the International Criminal Court’s rules, a witness must be a specific person or several persons who can testify and answer the prosecutor’s questions.

Cooperation between the Ministry of the Environment, Ministry of Defense, Ministry of the Interior, and other state institutions made it possible to develop a single data collection algorithm.

When a war crime is documented – for example, the shelling of the Rivne oil depot by Russian missiles – it is important that all institutions work together. The Environmental Inspection Agency drew up a regulatory instrument regarding evidence collection. The Space Agency provided satellite data. The National Police drew up a report in which it documented witness testimony by people prepared to appear both in the Ukrainian and international courts. So, official sources will exist that will confirm the information, thereby creating a “gold standard.”

Of course, in order for all this to work, there must be clear instructions describing the actions of all authorities when collecting information about a crime. Unfortunately, there is no such functioning mechanism in Ukraine at present.

AO: There is a lot of talk about ecocide happening in Ukraine now. What exactly is ecocide and can we really link it to this war?

OK: Ecocide in Ukraine is not only possible, but should be discussed today. Of course, neither international nor domestic legislation was prepared that – in the 21st century, almost a hundred years after the end of World War II – we would face ecocide in the heart of Europe.

The very legal definition of the concept lacks clarity. Section 12 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code contains Article 441, titled “Ecocide”. It provides for punishment for “mass destruction of flora or fauna, poisoning of the atmosphere or water resources, as well as other actions that can cause ecological catastrophe.”

From the perspective of national law, the ecocide article is a more serious crime than genocide. That said, it’s also based on value judgments and does not define what ecocide is and is not. How many trees must burn to be considered “mass destruction”? How do we document pollution of the air and water resources? What is an ecological disaster? For us, as lawyers, it lacks the specificity that would allow us to use this article.

As of today, the Prosecutor General’s Office has identified 11 environmental crimes since the beginning of the active military invasion – that is, since February 2022 – that we define as ecocide. Perhaps the most significant of these include the shelling of the Rivne oil depot (which I mentioned earlier) and the captures of the Zaporozhye and Chernobyl nuclear power plants.

The International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute contains Article 8(2)(b), which does not directly mention ecocide. It does, however, echo Article 441 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code. It also addresses the mass destruction of flora and fauna and infliction of significant and long-term harm to the environment.

For us, as lawyers though, it remains unclear what “long-term” and “significant” harm mean. How do we measure it? Perhaps that is why Article 8(2)(b) has never been used in international criminal trials.

But it does exist, so we decided to collect data using the gold standard and submit an appeal to the court. That will allow us to either confirm its viability or demonstrate the impossibility of its application and the need to reformulate it.

Since “long-term and significant” harm is legally difficult to prove, today a group of international lawyers is trying to make this article part of another article on genocide that is better worded.

As for the ecocide article in Ukraine’s Criminal Code, unfortunately, it doesn’t work either. Since it appeared in 2014, it has only been argued once in court, when it was applied to the destruction of three trees: one white mulberry and two apricots. Then the trial ended in nothing, and the plaintiff’s motion was denied in the absence of a criminal offense.

Today, we are preparing several cases that focus, for example, on the destruction of oil depots, a case to which it is easier to apply the ecocide concept, in other words, to imagine the “large-scale nature” and “significance” of the damage caused to the environment and to demonstrate the negative impacts of emissions on soil, groundwater, and the atmosphere. Hundreds of hectares of burnt forests also fall under the definition of “large-scale character.” For this reason, we expect that the case will be decided in our favor, particularly given that the Office of the Attorney General shares the same point of view.

Applying the Rome Statute, we also want to pursue criminal responsibility for carpet bombing, an act that destroys the soil layer across large areas. Such bombings lead to widespread and long-term chemical poisoning. As a result, we are counting on significant reparations for the destruction of unique humus-rich soil cover that can no longer be used for agriculture.

AO: Is it currently possible to file lawsuits in international courts for environmental crimes?

OK: Here everything is the same as for any other procedural or legal practice. Today, cases involving criminal investigations and presenting evidence prepared according to the gold standard can be submitted to international courts. However, if an investigation is ongoing – for example, analysis of chemicals resulting in environmental poisoning – then cases may be submitted to the prosecutor’s office at the completion of the investigation.

Our organization collaborates with international lawyers from the Netherlands and Finland to assemble and prepare cases for presentation in international courts. We have experience in filing cases with the European Court of Human Rights. We have carefully reviewed case studies for prosecuting environmental crimes during numerous military conflicts. And, most importantly, we have a strong desire to win and be paid reparations for environmental crimes. Therefore, I think it is safe to say that the outcome of the case will be in Ukraine’s favor.

The fact that the first appeal to the international court regarding crimes against the environment will be submitted by EPL is, in my opinion, of great importance. On the one hand, the Prosecutor General’s Office may take our experience into account during preparation of the cases. On the other hand, the fact that a civil society organization is taking the initiative should inspire government agencies to work more actively to modernize Ukraine’s legislative framework as well as developing and adopting normative acts to meet global standards.

AO: On a side note, what do you think about the July conference on Ukraine’s reconstruction in Lugano? Ukraine’s proposed Green Recovery plan was criticized by environmental organizations and was even called “shameful”.

– Yes, indeed, looking at the environment and Ukraine’s Green Recovery, environmental organizations have already called the submitted plan “the Shame of Lugano”. So, although Ukraine’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment postures itself as having worked with 211 experts and civil society representatives on the plan, its final version was not presented to the public, nor was it approved by independent experts.

In other words, the final version presented in Lugano was not approved by Ukraine’s environmental organizations or civil society. Moreover, some of its proposed programs are completely antithetical to a sustainable and environmentally friendly approach to the environment.

For example, the plan approved construction of new nuclear reactors, a move that conflicts with the European Green Deal. It is also expected to increase production of traditional fossil fuels, in particular, shale gas development, an industry that can cause significant environmental damage in the Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Lviv regions. It could also leave the Lviv region without water.

The plan also provides for the development of new inland waterways, which, in particular, may mean resumption of construction on the [international waterway] E-40. Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Polish environmentalists actively opposed this waterway, forecasting destruction of the Polesye ecosystem.

When presenting the final version, the Ministry actively referred to the European Green Deal. For us, as lawyers, however, it is not clear how this relates to Ukrainian legislation or which regulatory document spells out the principles of implementing this course in Ukraine. In addition, this reference turned out to be rather crafty. For example, in accordance with the European Green Deal, the construction and use of waste incinerators is prohibited, while in Ukraine their installation is planned in almost every regional center.

Therefore, from the perspective of protecting the interests of the environment, the plan for Ukraine’s recovery at the conference in Lugano needs revision. It is fundamentally critical that it represents the interests and position of environmental organizations and civil society. It is civil society and not those corporate lobbyists who apparently strongly influenced the recovery plan that will help to ensure that Ukraine’s recovery contributes to the Green Transition and achievement of carbon neutrality goals throughout Europe.

Translated by Jennifer Castner and Sara Moore.

Image credit: dif.org.ua

Comments on “Interview with Olena Kravchenko of the NGO “Environment-People-Law””