Fyodor Severyanin

Translated by Jennifer Castner

New data was presented on additional greenhouse gas emissions resulting from military activities in Ukraine at the UN COP28 climate conference that ended in mid-December in Dubai, UAE.

Consequences of 18 months of war

By December 2023, the United Nations reported that the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine had killed more than 10,000 civilians and injured more than 18,000. The World Bank has estimated the cost of restoring Ukrainian infrastructure at $411 billion.

The war has also had a serious negative impact on the environment – one of the most serious consequences being the increase in greenhouse gas emissions linked to the military conflict.

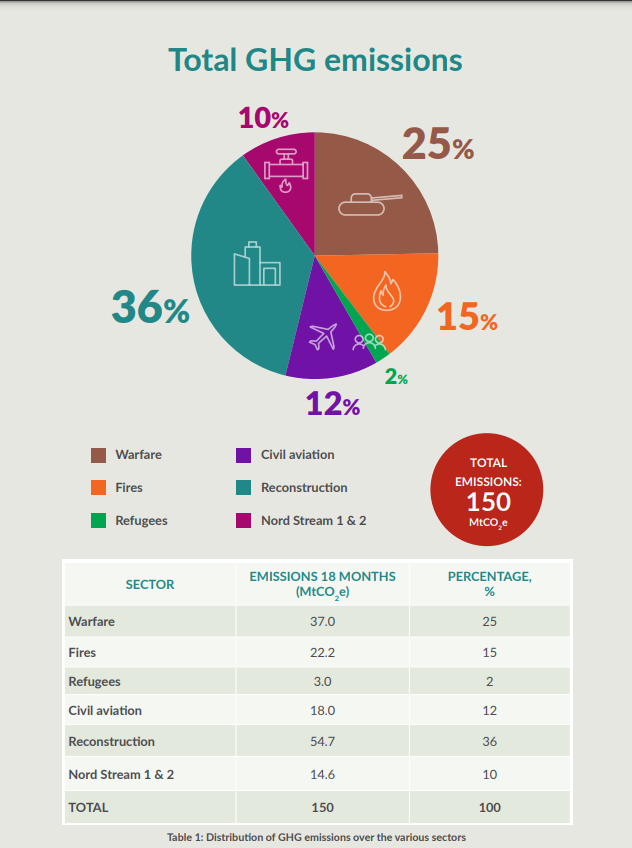

According to the Ukrainian NGO Ecoaction, over 150 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) were emitted into the atmosphere over the last 18 months of the conflict – that amount is equivalent to Belgium’s emissions for a year and is estimated at approximately $9.6 billion in cost.

The report’s authors argue that such emissions not only exacerbate the climate crisis, but also divert resources from environmental initiatives in Ukraine as the country focuses on reconstruction and defense.

New report on climate damage

The 28th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in Dubai, UAE (COP28) presented data on the climate costs stemming from the war in Ukraine and discussed ways to minimize defense sector climate impacts.

The methodology for calculating greenhouse gas emissions is outlined in Ecoaction’s report “Climate Damage Caused by Russia’s War in Ukraine,” based on a detailed analysis of emission sources resulting from the conflict.

Initial estimates of climate damage presented a year ago at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh considered emissions associated with refugee movements, military action, and fire.

Subsequent assessments, including the one presented at the June 2023 UN Interim Climate Conference in Bonn, expanded that initial scope to the first 12 months of the conflict with a focus on its impact on Europe’s energy sector.

The next assessment in the report covers a period of 555 days since the start of the conflict and highlights the need to hold Russia accountable for climate damage.

The report proposes methods for valuing climate damage in monetary terms and explores legal mechanisms for obtaining compensation. The option of using offsets to mitigate the consequences of greenhouse gas emissions in Ukraine is also being considered.

Evaluating emissions

Data on greenhouse gas emissions were obtained from various sources, including fossil fuel consumption, areas affected by fires, or the number of damaged apartment buildings. The war is ongoing and many data sources are unavailable or have limited access for security reasons.

For example, visual inspection is often impossible due to security issues, the mobilization of qualified personnel to defend the country, or due to territories being occupied. Consequently, satellite remote-sensing and reliance on indirect data are often the only options availables. The report’s authors contend that these estimates are based on many assumptions subject to future revision.

Emissions caused by military operations are estimated at 37 million tons of CO2e, while those caused by fires amount to an additional 22.2 million tons. However, the largest source of emissions lies in the future: potential emissions associated with post-war reconstruction, an amount estimated at 57 million tons of CO2e.

Damage compensation

Ecoaction’s report emphasizes that Russia must be held accountable for these emissions, despite the absence of clear international enforcement mechanisms.

Cumulatively, an additional 150 million tons of CO2e were emitted, and they certainly come at a cost to both climate and society. The report’s authors suggest that assessing the climate damage caused by Russia’s war requires setting a price for each ton of CO2e.

The most authoritative and widely used pricing scheme in their opinion is the “shadow” carbon price, based on a 2017 study by the High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing, led by Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern.

That scheme is based on the Paris Agreement’s goals of keeping global warming well below an increase of 2°C. This metric produces high and low carbon price recommendations, starting at US$40/$80 in 2020 and rising to US$50/$100 by 2030.

This evaluation mechanism is widely used. In particular, it is used by several international financial institutions, such as the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

The credibility and widespread use of the shadow price methodology established by that Commission allowed the report’s authors to choose it when analyzing emissions from war.

Since the shadow price for 2022-2023 averaged $64 per ton of CO2e, September 2023 calculations estimated total greenhouse gas emissions from Russia’s military intervention at $9.6 billion.

The authors emphasize that holding states accountable for their impact on the climate in a military conflict is a difficult task in the context of contemporary international law. They point to active debate on the subject, supported by the efforts of the International Law Commission and the International Court of Justice. The report highlights the UN’s recognition of the serious environmental consequences of armed conflict that can exacerbate global problems such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

The report also describes efforts by Ukraine and its international partners to ensure Russia is held accountable for damage from aggression. The authors draw attention to the development of an international reparations mechanism under the auspices of the Council of Europe that includes compensation for losses suffered by Ukraine and other countries.

They also highlight the importance of including climate change-related losses in the reparations framework. They point to political consensus around the concept, despite the thorny question of funding. The report also discusses possible international criminal proceedings, which could include charges of environmental crimes and the role of private companies that can use arbitration mechanisms to recover climate-related losses.

Green recovery

Ukraine has several methods for compensating damage resulting from the war.

The authors of the report note that one of the most obvious ways is to restore forests in burnt areas and other nature-oriented solutions. Sustainably managed forests can recover and absorb carbon dioxide emissions, although the process can take considerable time.

The potential for accelerated deployment of renewable energy in Ukraine, including wind and solar power, was highlighted as a way to reduce war-related emissions. They propose investments in decentralized power generation capacity, grid modernization, and energy storage as means to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels. Ukrainian energy industry corporation DTEK launched a Ukrainian national initiative to increase renewable energy generation in response to the global “30 by 2030” initiative. The initiative will increase renewable energy production in Ukraine to 30 GW by 2030.

The third method being considered is low-carbon rehabilitation of damaged buildings and infrastructure. The report’s authors analyzed ways to minimize emissions stemming from construction and discussed the sources of these emissions and approaches to a low-carbon recovery. They distinguish between embedded carbon (building materials) and operational carbon (energy use), exploring how the carbon footprint can be reduced at different stages of construction.

For example, concrete’s carbon intensity can be reduced by adding crushed granulated blast furnace slag (byproduct of the metallurgical industry), pulverized fuel ash (byproduct of coal combustion), and fired clay, wall of which are readily available in Ukraine and can significantly reduce the cement content of concrete. There are also alternative types of cement, e.g. cements produced using less limestone or using processes that require less energy. Improvements to the cement production processes are also being considered to reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions during clinker brick production.

The authors highlight their conclusions that approximately 50% of emissions during reconstruction come from building and industry and underscored opportunities to reduce them. They also describe ways to encourage the construction industry to reduce emissions as a whole and suggest the necessary next steps toward that goal.

According to Alexey Ryabchin, former Deputy Minister of Energy and Environment of Ukraine (2019-2020) and moderator of the event at COP28, the question of when Ukraine will be able to receive compensation from Russia as an aggressor could serve as the basis for creating an “aggressor pays” mechanism that is similar to the “polluter pays” principle. Perhaps this mechanism could be used in the future to prevent new conflicts.

Main image source: Climate damage caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine report