Ukraine Nature Conservation Group position

Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Viktor Parkhomenko, Ivan Moysiyenko, Viktor Shapoval, Serhiy Panchenko, and Oleksandr Spriahailo all contributed to this article.

First published by the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group’s website in Ukrainian on 14 August 2023. The authors recognize Dr. Eugene Simonov for his important advice.

Alastair Gill and Jennifer Castner provided editing in English.

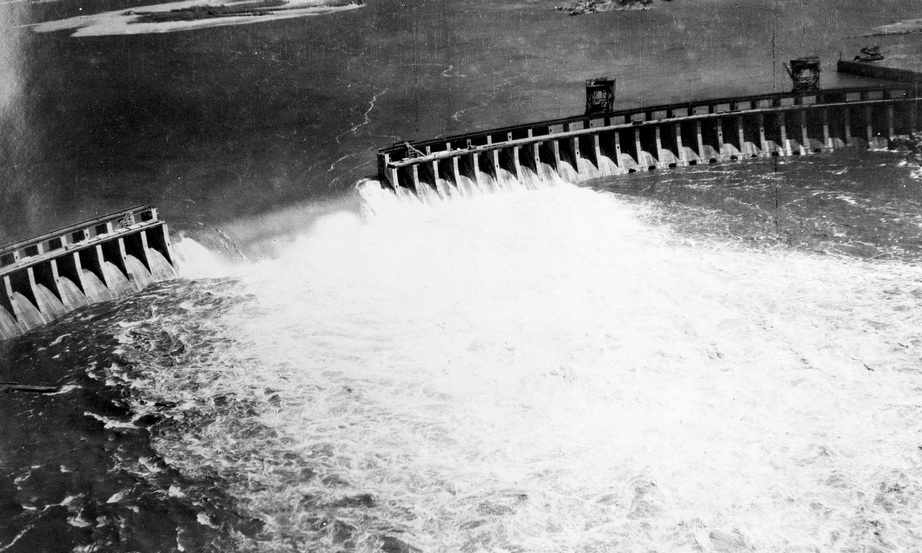

Velykyi Luh (meaning “Great Meadow”) is one of Ukraine’s most important natural and historical landscapes. Despite the presence of many monuments from the age of the Zaporizhzhian Sich and a large number of rare animal and plant species, the area was flooded in 1955-1958 during the construction of the Kakhovka Reservoir. For 70 years, Velykyi Luh was lost to nature, science, and Ukrainian culture. But on June 6, 2023, as a result of the destruction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant (HPP) dam by the Russian military, the reservoir ceased to exist within weeks, putting Ukraine at a crossroads. Now it is necessary to make a historic decision: to restore the natural ecosystems destroyed in the past on the site of the former reservoir, or to build a new HPP and refill the reservoir. In our opinion, the very idea of reviving Velykyi Luh as a natural area is not only timely and environmentally justified, but such a decision would also go a long way to offsetting the wildlife losses caused by the war.

Restoring natural ecosystems where they have degraded (and not just saving those that remain) is the modern basis of sustainable development in Europe. In recent years, European states have increasingly taken bold and visionary decisions aimed at stopping global climate change and guaranteeing a reliable future for the entire continent. In May 2020, the European Commission presented the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2030, perhaps the most ambitious environmental protection document in the history of Europe. The strategy contains specific obligations and actions to be implemented in the EU by 2030. The document has a number of extremely ambitious goals: at least 30% of land and 30% of marine water areas should become protected areas; at least 10% of agricultural land should be removed from cultivation and restored to natural ecosystems, pesticide use should be reduced by 50%; and at least 25,000 km of rivers should be restored to a free-flowing state.

In July 2023, the European Parliament adopted the Nature Restoration Law, which aims “to put restoration measures in place by 2030 covering at least 20% of all land and sea areas in the EU.”

Accordingly, half of land in European countries should become either protected (30%) or restored to their natural state (20%) in the next seven years. Humankind has never set more ambitious nature protection goals. However, the statistics predicting catastrophic scenarios for humanity in the coming decades are more than convincing, meaning we will need to pay far more attention to ecosystem restoration and the relationship between people and nature. Undoubtedly, the accession of Ukraine to the EU will require the fulfillment of these goals as well. And, in this regard, the restoration of Velykyi Luh has clear potential to be a truly unprecedented model project, larger than any Western European local initiative.

The Dnieper River is one of Europe’s most important waterways both for people and biodiversity. Peoples migrated along it and various states took shape: the former Kyivan Rus, the Ukrainian Cossack State, and modern Ukraine were all formed around the Dnieper River basin. A useful water transport artery, a powerful intrazonal corridor with a mild climate, protected by forests and terrain from harsh steppe conditions, incredibly rich in fish and fowl – in the past these qualities made the river an exceptionally attractive location for state-building. However, in the 20th century a number of reservoirs were created here, bringing significant changes and a pronounced negative impact on the river’s hydrological conditions. Now, after the explosion of Kakhovka Dam, the process of returning the Dnieper floodplain to its natural state has begun. Dam removal to restore natural processes in river ecosystems is in line with today’s leading practices.

Velykyi Luh is an important natural and historical landscape of extremely important cultural value for Ukrainians.

The very fact that the Zaporizhzhian Sich (Ukrainian Cossack State) once occupied this territory makes it a site of great natural and historical importance for Ukraine. And although this part of the Dnieper valley is the cradle of Ukrainian statehood and contains a colossal concentration of historical and archaeological heritage, this particular site is practically unstudied by historians and archaeologists.

The inhabitants of this area – 90 villages and farms home to 37,000 native residents – were forcibly resettled in the 1950s. Before the creation of the reservoir, this area consisted mainly of the Dnieper River’s natural floodplain. Looking at the local relief, clearly visible now that the reservoir has disappeared, it can be argued that this territory was home to the most diverse and dynamic landscape in Ukraine. The area played a significant role for local biodiversity and even more so for global seasonal bird migrations. Since the 1920s, scientific and state institutions have sought to create a reserve here.

The creation of the reservoir created environmental and social problems.

When developing plans for Ukrainian hydroelectric power plants and reservoirs, the Soviet authorities did not include the value of the land lost in the estimated cost of construction. Kakhovka Reservoir covered large areas with fertile soils, destroying both agricultural land and forests, meadows, marshes, and old forests where many rare plant and animal species were found. More than 100,000 hectares of fertile lands were flooded and taken out of agricultural use, and even larger areas were inundated (both the reservoir itself and the irrigation systems created there).

More than 15,000 collective farmers, workers, and employees were subject to forced eviction from the reservoir zone, and more than 3,000 buildings on the state balance sheet had to be relocated, destroying economic and social ties that had developed over centuries in a densely populated region. Resettlement conditions were discriminatory and economically disadvantageous for the population. People had to transport their own houses and auxiliary buildings and build new ones from the ruins. At the same time, collective farm buildings had to be transported and rebuilt. Extraordinary measures were taken against those who did not manage to resettle in time, including forced resettlement and the destruction of homes.

In the first years after the reservoir filled, houses in adjacent settlements began to collapse and hundreds of hectares of land along the shore “slipped” into the water as a result of erosion. In a number of villages located 300-500m from the shore, cracks 1.5-2.5 km long formed in the earth. Consequently, in 1958 the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR declared a 100 m-wide strip of steep bank as dangerous and prohibited access. Each year, 1-7.5 meters along the shore erode into the reservoir, expanding its surface area and reducing its depth.

Since then, approximately 10,000 hectares of land have been lost in the vicinity of “Kakhovka Sea”. Eroding shorelines quickly silted up the near-shore zone for 200-500 m and made it impossible to pump water from near the reservoir itself. Finally, cemeteries and cattle burial grounds were flooded. The relocation of the displaced population to more elevated areas, often without water, coupled with incredibly slow construction of new water lines, meant that water had to be delivered to most of the new villages. This was a significant reduction in quality of life and wealth for those resettled and led to accelerated migration of the region’s population, primarily young people, to cities.

Mistakes and miscalculations by the reservoir’s designers pushed the water level 2-3 meters higher in some places in Kamian-Dnieper District in Zaporizhzhya Oblast, resulting in destroyed wells, flooded cellars, waterlogged land, and sagging houses. Even 20 km from the reservoir, groundwater rose to just 60-80 cm below the soil, threatening gardens and vineyards and waterlogging meadows. 6,730 hectares of gardens and 6,700 farms were flooded in 1957 alone. Flooding of the region continued until 2023. As a result soil salinity increased and several large garden areas became unusable, among them a magnificent 660-hectare garden in the village of Vodiane.

The promises made by the reservoir’s proponents boiled down to the obvious boost for all sectors of the economy. Despite that optimism, not all of these promises to improve life came true. Plans to increase yields of winter crops, cotton, etc., as well as plans for growing shallow-water crops (rice, vegetables, etc.) failed. The same applies to plans for breeding unprecedentedly large volumes of sturgeon and other valuable commercial fish species which instead disappeared from the reservoir altogether and were quickly replaced by low-value introduced fish species. In 1956, just before the reservoir began to fill, the fish harvests totaled 90,000 tons. In 1966, the annual fish catch in the Kherson region amounted to just 1,300 tons. Native fish species populations declined due to pollution, siltation, loss of rheophilic conditions and spawning grounds, and also the inability to swim upstream for spawning. In addition, algal blooms and poor oxygenation led to the disappearance or reduction of fish sensitive to oxygen content in the water, and populations of low-value species that can tolerate brackish water and withstand high water turbidity increased.

The pollution of Kakhovka reservoir’s water and bottom sediments was also problematic. Accumulated river water and the entire cascade of reservoirs upstream determine the chemical composition of Kakhovka Reservoir’s waters. Existing water treatment facilities in the Dnieper basin are unable to sufficiently purify wastewater. The main sources of surface water pollution are overloaded sewage treatment facilities and drainage networks that are in poor technical condition. More than 90% of the polluted wastewater in the Dnieper River basin originates in urban sewage canals in Dnipro Oblast and from industrial enterprises in the vast mining and metallurgical complex of Dnieper, Kamiansk, Kryvyi Rih, Nikopol, and western Donbas. The average annual content of harmful substances in Kakhovka Reservoir reached dangerous levels: 1-2 maximum permissible concentrations (MPC) of phenols, 6-11 MPC of copper compounds, 7-12 MPC of zinc and 3-10 MPC of manganese.

From the very beginning, when Ukrainians were forcibly resettled in 1954, people had a negative attitude towards the project. Construction went ahead nevertheless, and by the 1950s, censors strictly forbade any mention of the problematic reservoirs in newspapers. Many editors and journalists ended up in Soviet prison camps for reporting on the negative consequences of the construction of hydroelectric power stations. More recently, environmental scientists from Nikopol and Zaporizhzhia and specialists from Dnieper National University and others sought to reduce reservoir water levels.

Resistance would have been much greater, but after the repressions of the 1930s, the national liberation movement activists, professional historians, biologists, and local historians capable of battling the construction of the hydroelectric cascade were either shot, evicted, or found themselves in extremely difficult conditions and under constant checks, when one wrong step was immediately punished.

Construction of the Dnieper reservoirs, and in particular the rather shallow Kakhovka – the second largest in terms of area and the largest in volume – created a significant number of environmental problems, both for people and nature.

Construction and then filling of the reservoir made it almost impossible for the inhabitants of the left and right banks to communicate. Villages that were previously separated by a floodplain and a relatively narrow river were cut off from each other by a much wider and deeper water barrier. Residents of neighboring villages, who had previously actively socialized with each other, built families, and participated in a shared economy, now had to travel hundreds of kilometers in an overland detour through Kakhovka or Zaporizhzhia. Their connections were completely lost, and many families were splintered.

The creation of reservoirs also had a severe impact on river transport. Ships were forced to wait for days, or even weeks, for the passage of vessels through the locks of the HPP. A huge freshwater reservoir like Kakhovka is also extremely dangerous for all types of craft in stormy weather. Given those conditions, there was an unsurprising decline in river transport.

According to published data, after the construction of a six-reservoir cascade on the Dnieper the transportation of goods by water transport fell from 30,800 tons in 1980 to 3,000 tons in 2009 – over tenfold. Over the same period, the number of river passengers decreased from 25,000 to 1,500. The reasons for these rapid declines may be different, but the fact itself refutes arguments for any pivotal role by the dam and reservoir on navigation on the Dnieper River.

Would a project on the scale of the Kakhovka reservoir seem justified in 2023?

Despite the significant societal impacts resulting from the destruction of the Kakhovka HPP, it should be recognized that the economic value of the Kakhovka reservoir in 2023 was insignificant for the state. Ultimately, artificially introduced fish were harvested, and the HPP produced an insignificant amount of electricity.

Other arguments made by today’s advocates for restoring the reservoir are related to uses that can be fulfilled by a free-flowing Dnieper. Water for drinking water and irrigation was supplied by pumps; water transportation is more convenient without locks and high waves arising from the wind’s long fetch across the reservoir’s surface. Some authors suggest that the reservoir had beneficial climatic effects for surrounding settlements, but these theories are very doubtful: although residents of settlements on the shore of the reservoir actually felt an improvement in the microclimate due to the additional moisture content in the air, the state lost 1.3 km3 of water per year due to evaporation.

In general, the impact of the construction of the Kakhovka reservoir for climate change and the region’s natural characteristics is not well-studied, and there is insufficient data. The opportunity to conduct comprehensive monitoring and multifaceted assessments has only recently become available. In any case, changes in microclimate over much larger areas are due to the influence of irrigation systems and may not require restoration of the reservoir.

On the other hand, long-term trends of water quality deterioration and stagnation processes in the reservoir are dissonant with ecosystem services and cannot be ignored. The death and decomposition of blue-green algae produces significant quantities of poisonous chemical compounds: butyric acid, acetone, ethyl and butyl alcohol, ammonia, organic nitrogen, phosphorus compounds, etc. They not only smell bad, but asphyxiate and kill fish, lead to disease in domestic animals that consume the water, complicate the operation of canals (when filters get clogged), etc. Additionally, cyanobacteria toxic products (hepatotoxins, neurotoxins and dermatotoxins) can be dangerous for humans as well. Their active reproduction in reservoirs is often associated with the development of intestinal diseases, allergic dermatitis, liver disease, and even an increased risk of cancer. The problem is further aggravated by the introduction of cyanotoxins into drinking water distribution networks – there are no standardized methods for their detection in Ukraine. Consequently, cyanotoxins cannot be verified or neutralized during the water treatment process.

While oxygen production by phytoplankton during algae blooms is beneficial, invasive plant species are involved in the cycle as well. The overarching problem is that instead of natural areas with native biota and well-developed self-regulation mechanisms, artificial reservoirs created unstable, anthropogenically-transformed ecosystems.

Today, no EU country would finance and implement the construction of a new hydropower plant and reservoir on the scale of Kakhovka dam and reservoir. The cost of such a project appears completely senseless compared to the demands that can be met solely through a reservoir. Most EU countries are engaged in emptying much smaller reservoirs due to their ecological impracticability and are not building new large reservoirs.

In the end, time is against the restoration of the reservoir and the entire hydropower system. There are currently no definite projects or funds for their implementation, or even the means of carrying out such work. On the other hand, the economic infrastructure that is critically dependent on the functioning of the water reservoir is not secure enough to simply wait for restoration. The challenge of supplying water to settlements and agricultural land dependent on irrigation is already being actively solved using alternative methods. Agricultural producers are being forced to swap thirstier crops for drought-resistant ones, and the adaptation process to new realities is taking place independently and in contradiction to as-yet ambiguous prospects for restoring reservoirs.

Most of the land affected by the reservoir’s emptying is currently unsuitable for agricultural use due to pollution, minefields, and temporary Russian occupation. Consequently, restoration of natural vegetation in these areas can be considered an ecosystem remediation measure. According to Article 172 of Ukraine’s Land Code and Article 51 of Ukraine’s Law “On Land Protection”, areas subject to temporary closure include “degraded lands, unproductive lands lacking steppe, meadow, or forest vegetation cover, the economic use of which is ecologically dangerous and economically ineffective, as well as industrially-polluted land plots on which it is impossible to produce ecologically safe products, and the presence of people on these land areas is a public health risk; land areas contaminated with chemical substances as a result of emergency situations and/or armed aggression and hostilities during martial law.”

The Russian terrorist attack on Kakhovka HPP caused unprecedented environmental losses and created new environmental challenges.

Many problems stemming the reservoir’s creation and existence disappeared when the reservoir emptied. However, the terrorist attack on Kakhovka HPP caused devastating short-term consequences and created many new problems that did not exist before. Most of the reservoir’s fish population and aquatic organisms were destroyed (most were washed into the Black Sea and died); benthic fauna and aquatic vegetation dried out and died (and their decay created public health risks); whole colonies of birds died and whole riparian aquatic vegetation ecosystems disappeared. Drained landscapes also affected protected areas Velykyi Luh and Kamianske Sich National Nature Parks.

The rapid outflow of water wiped out fauna in the flooded area, from large mammals to small insects and even fish, swept into the Black Sea by the current. As a result, Lower Dnieper National Nature Park and several nature refuges lost their natural value. Even more protected areas were flooded, and several endemic species of plants and animals are now threatened with extinction due to increased groundwater levels.

At least two species of insect (European ant Liometopum microcephalum and Kinburn ant Tapinoma kinburni) and one species of fish (Estuarine perch Sander marinus) have likely been wiped out in Ukraine as a result of the flooding.

Almost all the flooded lands below the dam and drained areas of the reservoir are classified as nature conservation territories of international importance.

Freshwater contaminated with silt from the reservoir’s bottom, debris from buildings and infrastructure, vegetation, and animal corpses were flushed far into the Black Sea, reaching the shores of Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania a few days later. This flood resulted in the colossal desalination of the sea’s most biologically diverse coastal strip, as well as its pollution. That, in turn, led to the destruction of marine organisms.

The destruction of the dam created a whole series of unprecedented consequences and new problems for people. Water supply to cities and irrigation from water intakes that pumped water from the reservoir were halted for the time being. The Kakhovka HPP and the bridge crossing it have ceased to exist, and river navigation has become temporarily (until the dam’s complete dismantlement) impossible. In addition, stable operation of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant was thrown into jeopardy.

Velykyi Luh can be restored as a natural area.

While highly visible, the exposure of the reservoir’s bottom – hastily described by mass media and elder environmentalists and ecologists in Ukraine as “desertification” – is a short-term negative impact. Firstly, the reservoir was a source of evaporation, and therefore water loss, in the region. Secondly, the almost lifeless shallows stretching endlessly are not a natural ecosystem and remained an artificial structure for 70 years. Undoubtedly, the “desert” landscape here will, in the near future, be overgrown with natural vegetation and become the largest area of natural wilderness in Ukraine’s steppe zone.

Our expedition to the Kharkiv Oblast’s Oskil Reservoir (also drained subsequent to dam damage during the Russian invasion in early 2022) revealed that natural ecosystems attractive to birds had already recovered in the first year. Studies conducted on specific areas of the former Kakhovka Reservoir have shown that just a month after the water release, vegetation had already begun to recover in some areas. Moreover, research carried out near Kamianske Sich National Nature park, showed that native species seedlings (among them the white willow Salix alba being the most frequent) significantly outnumber alien plant species on the dry reservoir bottom.

Predictions of dust storms have also turned out to be unfounded: the hottest part of the summer has already passed, but no dust storm caused by the blowing of silt from the reservoir bottom has occurred. As the precipitation increases in fall and the basin bottom is covered with vegetation, the probability of dust storms will decrease significantly.

In this context, the intensity of the spontaneous recovery process and the ability of vegetation systems to self-renew cannot be underestimated. Calls to plant wild grasses (and others) are absolutely hasty, unfounded, and unrealistic. Anticipated wind erosion is being solved by nature itself, with bare areas of soil actively sprouting vegetation and anchoring the soil in place, bringing into question any plan for “seeding”. The questions of what to sow and where to obtain the necessary quantities of seed material for suitable wild plant species? They are not available in the required amount, and in practice we have to use hay containing a seed fraction, given the difficulty of its separation. Lastly, all classic agro-steppe methods involve pre-sowing soil preparation, the use of special agricultural machinery, and step-by-step seed care, all impossible due to ongoing hostilities in the region. Thus, the proposed and fully explained measures to counteract wind erosion will be irrelevant by the time their implementation becomes possible.

It is very difficult to model the restoration of vegetation cover. By analogy, we can say that a complex of aquatic and coastal, wetland, meadow, and forest vegetation will form at the bottom of the reservoir. The key challenge to natural vegetation restoration will be insufficient seed availability. This will have the smallest effect on aquatic and swamp vegetation: seeds belonging to aquatic plants float, and rivers and large lakes can serve as dispersal corridors. Seeds for plants that form the basis of meadow and forest communities will be critical; seeds can be transferred by wind, but are more often dispersed by animals, a function that depends on intact, interconnected ecosystems. Wind-sowed plants, such as the aforementioned white willow, will be most successful in colonizing the bottom of Kakhovka reservoir. In the case of willow, seasonality is also important. Shortly before the dam was blown up, the fruits of willows ripened, and scattered seeds using fluff that floated on the water surface, and now we see numerous sprouts. The elm also behaves in a similar way. In many other plants, seeds ripen later and will fall onto the newly formed land. Meadow and forest vegetation cover will gradually advance from the periphery to the center of the former reservoir.

Synanthropic species will play a key role in the first stages of vegetation regrowth in dry areas, including a significant share of invasive species. They have a wide arsenal of seed dispersal methods and can produce huge numbers of seeds. As a result, the bottom of the Kakhovka reservoir will somewhat resemble the abundant vegetation found on dumps and landfill sites.

Another factor that does not lend itself to analogy is the condition of the substrate. Fairly thick bottom sediments formed over many years, and to a large extent they have leveled out soil fertility, whereas natural floodplains vary significantly, with higher and lower areas. This effect will also contribute to the intensive development of plant species characteristic of such rich substrates. At the same time, for birds, an area with a complex mosaic of lakes, shallow waters, meadows, forests, and even sand dunes will be incomparably more valuable than lifeless shallow waters. Restored floodplain ecosystems provide habitats for many species important for nesting, feeding, and resting during migration. Considering that a restored Velykyi Luh – ‘great meadow’ – will have an area much larger than any area of nature preserved to this day in Ukraine’s steppe zone, it can be assumed that it will become the most important natural area for the entire south of the country.

In the first years, an important influencing factor will be the nature of flooding: how high the spring waters rise, how long they stagnate in lowland areas, etc. During spring flooding, formation of the Dnieper River and floodplain will be particularly intensive, old lakes will be flooded and new depressions will take shape.

We are optimistic about the restoration of natural vegetation and predict a relatively quick renewal of aquatic, coastal, and wetland vegetation. Dry land areas will be dominated by plants characteristic of invasive weed-covered areas for some time, but in 5-10 years, areas with predominant tree cover will be visible and the first forests of willow, alder, elm, ash maple will form. Considerable areas will be occupied by thickets of shrubs (Amorpha fruticosa) and willows (Salix alba). Two to three generations of pioneer trees can be anticipated prior to the formation of more or less natural and sustainable forest ecosystems. Restoration of meadow vegetation is difficult to predict, because it will depend on land management. Left untouched by humans, these will be insignificant areas of meadow surrounded by thickets of reeds, forests, and shrubs.

Restoring Velykyi Luh is in the interests of the environment.

In the distant past, the largest natural forest in Ukraine’s steppe zone grew on the site of what was Kakhovka Reservoir. (It was named Velykyi Luh because in Ukrainian, unlike the word luky, meaning meadow and grass ecosystems in river valleys – the word luh literally meant floodplain forest). It could be incredibly advantageous for implementing Ukrainian government plans to increase forest cover and the ability to carry out these tasks in a natural way, without harming other ecosystems. Part of the area will be naturally overgrown with meadows. It must be recognized, however, that the focus here is ecosystem restoration: a recovery similar to and even very close to lost natural systems. These native ecosystems were finely tuned and formed as a result of the centuries-old interaction and interference of a number of natural and anthropogenic factors that were in unique balance.

The restoration of semi-natural ecosystems across such a huge area has many positive consequences:

- Diversity of natural ecosystems will increase significantly: instead of almost identical biotopes of the artificial water bodies which occupied more than 90% of this area, dozens of other biotopes will appear, in particular, swamp, meadow, steppe, shrub, forest, halophyte;

- Absorption of greenhouse gases will significantly increase due to the rapid growth of woody plants (Ukraine has committed itself to decarbonization);

- Carbon dioxide absorption will increase significantly (relevant given Ukraine’s obligations regarding decarbonization);

- Populations of many rare species included on Red Lists due to the threat of extinction will increase in size; significantly reducing threats to survival. In particular, it will be possible to prevent the almost inevitable disappearance of some local endemics, such as cornflowers Centaurea appendicata and Centaurea konkae;

- Areas of pasture and hayfields will increase;

- Available stocks of valuable wild plants and animals – medicinal, domesticated, hunting, etc. will increase grow

- Fish spawning will resume, significantly enriching the fish population of the Lower Dnieper and eliminating the costs of maintaining several fish farms (which previously ensured the artificial renewal of fish resources);

- Freshwater evaporation will decrease due to reduced water surface area;

- Water quality and the condition of aquatic ecosystems will improve; and

- Diversity of water body types will increase significantly.

Human advantages of draining the Kakhovka reservoir.

Analyzing the situation in its current state, draining the reservoir may have tangible advantages for the population. For example, water-based transport will now be able to move at all times of the year and will not have to queue at river locks; bridges and ferries will be built and crossing times will be reduced tenfold, this will facilitate converting an economically depressed region into a logistics center that will no longer be isolated from central highways and will be the most convenient in the region for transport logistics. New opportunities to develop solar energy in recently drained areas will also be possible. From an exclusively economic context, there is significant agricultural potential – as many as 200,000 hectares (or at least some fraction thereof) of land. And, of course, the war’s end will open up unprecedented opportunities for recreation and tourism development.

Benefits of draining the reservoir for Ukraine as a state and for Europe as a whole.

The area will become a platform for research on the restoration of natural ecosystems as well as the reintroduction of rare animals and plants. It will also be valuable to create a protected area here to prevent new crop agriculture or rebuilding the reservoir, both of which have already destroyed many unique ecosystems.

What awaits Velykyi Luh?

There are a number of options. At a minimum they are: 1) do not restore the reservoir, 2) restore it, or 3) build something completely different. It is obvious that from an economic point of view, these options will be prioritized in this order, and despite the objections of certain individuals, the cheapest option will be to not rebuild the dam. Even the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) has already announced that in 2023 alone, the consequences of the HPP’s destruction will reduce real GDP growth by 0.2%, increase consumer inflation by 0.3%, and increase the trade deficit by $0.4 billion. At the same time, according NBU’s calculations show that the cost of restoring the hydropower infrastructure and its water reclamation systems each cost about $1.5 billion. Roughly speaking, losses to the economy from destruction of Kakhovka HPP are much smaller than the funds needed to restore this outdated complex.

It is not surprising that Ukrhydroenergo’s management team insists that the only option for the future is to construct a new dam and re-fill the reservoir. Although energy industry officials frequently voice doubts that someone will take on the restoration of the dam, nevertheless, this option is the most commonly proposed of all the possible scenarios.

Restoring the reservoir will resurrect old problems and create new ones.

Ukrhydroenergo’s scenario does not consider environmental impact. Construction of a new HPP will entail all the negative environmental consequences that the creation of the reservoir brought in the 1950s and will reestablish all the chronic problems caused by the reservoir’s existence. Disruption of bottom sediments will no longer allow it to be used for fish breeding. Nature will not wait for government decisions and is already actively restoring ecosystems on the drained land. Until the possible construction of a new dam, the entire territory of the former Velykyi Luh will be green again and millions of living organisms will exist there. Refilling the reservoir will be comparable to the same ecocide of which we now rightly accuse Russia. To allow ourselves to frivolously destroy ecosystems at a time when such destruction is one proof of Russia’s war crimes is inconsistent at the very least.

In addition, restoration of the reservoir would be significantly more costly than the original construction, in part because of the impossibility of recreating the 1950s project. If restored, a new reservoir (and we hope that this will not happen) would have to be equipped with a fish ladder to operate across the elevation between the Dnieper and the reservoir surface exceeding 16m, require logistical solutions for cross-river connections (ferry, aviation), await engineering of modern embankments, resolve public safety issues in the potential flood zone with an extensive system of smaller saddle dams, and ensure large-scale reconstruction of the worn-out distribution network of irrigation channels, etc. Building a modern equivalent of the former complex of HPP, irrigation systems, and a safe reservoir presents a far greater and more expensive challenge than it did 70 years ago.

Nevertheless, it is sensible to question the expediency of this option even at the stage of assessing energy needs. According to data published by the Institute of Nature Management and Ecology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the entire cascade of hydroelectric power plants on the Dnieper produces 9 billion kW – just 5–7% of Ukraine’s overall electricity production in Ukraine.

Is it possible to meet Ukraine’s needs without restoring Kakhovka HPP?

In analyzing whether it is possible to meet Ukraine’s needs without restoring the reservoir, it must be understood that most of these needs will become relevant only after de-occupation of Ukrainian territories and demining; the latter process may take decades.

The situation with water transport and logistics is easiest to assess. Periodic dredging of the navigation channel will be sufficient for river transport, and in general the situation may be even better than during the reservoir’s existence. Intricate passage requirements through the reservoir, long queues at shipping locks, and the complete impossibility of winter navigation all served to complicate matters. In addition, large wind waves on the reservoir’s wide expanse during storms significantly complicated shipping.

Instead of the former ferry, the alternative to which was a detour around the entire reservoir (more than 200 km one-way), it will now be possible to build several modern, convenient bridges, the logistical practicality of which will also encourage road rebuilding throughout the region.

In the first months following the disaster, it was the supply of drinking water and irrigation that caused the most concern. Restoration of drinking water supply to cities like Kryvyi Rih and Nikopol was an urgent issue in the first days after the dam was destroyed, and repairs to pumping stations will be completed in the near future. If water supply is restored in the coming months, there will be absolutely no need for the reservoir’s reconstruction. The situation is similar with irrigation, for which water was also pumped into canals from the reservoir. If necessary, pumping stations to restore canal water supply can be rebuilt on the left bank of the former reservoir after de-occupation. Traditional resource-hungry methods of irrigation using sprinklers can be replaced by modern and economical drip irrigation technologies – in fact, irrigation agriculture in the region is in general need of modernization.

The challenge of irrigation is the most difficult, in our opinion. Existing canals and irrigation systems require large volumes of water. The amount of water required for irrigation should be calculated using the most economical options for irrigation agriculture. However, we must consider all possible alternatives to address this issue, including considering irrigation options that do not require rebuilding the reservoir.

If modern irrigation technologies are used, significantly less water will be required for the same areas, and the Dnieper’s natural flow will be sufficient to fill the water supply lines.

As for concerns about the operation of Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, its long-term functioning does not depend on the presence of a reservoir, but rather on its own cooling pond, which remains intact for the time being. It is also possible to supply it with water pumped from a channel of the Dnieper that is currently directly adjacent to the cooling pond.

Only one issue remains – the question of how to replace the electricity previously generated by the hydropower plant. The Kakhovka HPP generated 1.4 billion kWh per year, significantly less than 1% of Ukraine’s electricity generation, and that HPP’s role in the energy sector is extremely small.

Another key function, according to Ukrhydroenergo officials, is the ability to balance the energy system during peak demand. While this is a well-known feature of cascaded reservoirs, it was not the case with the Kakhovka reservoir. It should not have been actively used for peak regulation since there is no reservoir below it, meaning that sharp drops in discharge from the station would have had major detrimental consequences for the ecosystem and the population, including powerful erosion. In today’s world, energy industry alternatives are a) “smart networks” that redirect the energy produced by the system to peak times, b) batteries, c) power that is quickly accessible, for example gas (and in the future even solar), d) consumption regulation to smooth “peaks” (for example, by differentiating electricity prices by time of day).

The issue of energy spikes is not relevant for Kakhovka HPP, rather the concern is about the loss of maneuverability of the Dnipro HPP further upstream. There are three solutions here: a) find a safe place for a counter-regulator reservoir; b) transfer this function to other parts of the remaining HPP cascade; or c) a combination of the first two options.

15. Today our work is to prevent hasty decisions.

Now is not the time to blindly ask “How can we restore the reservoir?” Instead, we should seek to quickly and rationally meet the existing needs of our state and population using modern technologies and solutions. What are the benefits of alternative scenarios?

Making hasty decisions not based on the study of international experience, impartial development of multiple scenarios, or a strategic environmental assessment can only result in new damage and losses. Decisions of this magnitude entail such important consequences that accepting them under the pressure of lobbyists without extensive study of the issue and the input of all stakeholders will be an unacceptable mistake.

Despite this, our state has already made its first hasty decision. On 18 July, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine approved the resolution “On the implementation of the experimental project “Construction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station on the Dnieper River. Reconstruction after destruction of the Kakhovka HPP and ensuring stable operation of the Dnieper HPP during the reconstruction period.” This decision, adopted without proper environmental assessments and evaluations and the necessary detailed economic calculations, has already caused indignation among experts and public organizations. At the same time, lobbyists for the restoration of Kakhovka reservoir are presenting it as the sole option and the only possible solution to a number of problems: irrigation, logistics, energy, etc. This is completely untrue, and certain arguments openly manipulate public opinion. It is to be hoped that the unexpected renewal of Velykyi Luh, the memory of which Soviet ideologues sought to erase for decades, can become a symbol of Ukraine’s post-war recovery. The unique experience of Kakhovka Dam’s destruction has the potential to be engraved in the history of the Russian-Ukrainian war as an example of how Ukraine “built back better”.

Velykyi Luh’s restoration will be the largest environmental project ever carried out in Europe. Considering the scale of this undertaking, it is quite realistic to turn it into a pan-European one. European environmentalists, scientists, and governments will be interested in joining the largest natural ecosystem restoration project on the continent. Broad international cooperation will contribute to future success thanks to European Union countries that can share their extensive experience in carrying out similar work; Velykyi Luh’s restoration has the potential to become Ukraine’s decisive contribution to the EU’s commitment to restore 25,000 km of rivers to their natural condition by 2030.

Comments on “Is it time to restore Velykyi Luh?”