by Valeria Kolodezhna

Translated by Alastair Gill

UWEC Work Group member Valeria Kolodezhna sat down with Yehor Hrynyk, a biologist and specialist at Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, to talk about changes to conservation legislation in Ukraine, as well as environmental campaigns and activism in the country during wartime.

Hrynyk’s work involves anything related to Ukraine’s forests, from uncovering and documenting illegal logging to facilitating the creation of protected areas. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, unauthorized logging has increased, and lobbyists hoping to develop one of the best-preserved mountainous areas in Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountains are also becoming more active.

What main trends in nature conservation in Ukraine have you observed since the beginning of the war?

Since the beginning of the war, nature conservation in Ukraine has witnessed a serious regression. Even if the war ends in victory for us tomorrow, we would need several more years to return to pre-war conservation levels.

Laws are now being passed that essentially destroy wildlife – for example, forest management is being reformed and all forestry enterprises are being merged into one. Meanwhile, they are giving everyone the impression that this is being done solely in order to produce more timber.

National parks and nature reserves are also being told to earn as much money for themselves as they can. And even in reserves where regulations prohibit almost any activity, they are finding ways around this by doing things like making fire breaks – thereby cutting down huge areas of the forest.

Fire breaks are cleared areas in the middle of the forest that act as a barrier, stopping fires from spreading in a particular direction. But felling sections of forest to create cuttings is not the only way of fighting fires, and clearly a last resort when it comes to protected areas. The cases that we are now seeing bring only economic benefits.

Logging is even taking place in areas that have been mined. Just like last year, there were frequent cases of foresters being blown up by mines in 2023. Our report “How corruption threatens the forests of Ukraine: Typology and case studies on corruption and illegal logging,” which we prepared together with the Basel Institute on Governance, outlines the reasons loggers go to such great risk. To sum up, in the course of the investigation we came to the conclusion that the situation with illegal logging has only worsened in Ukraine since the outbreak of full-scale hostilities. And the main parties responsible for this logging are the foresters themselves.

The European Union (EU) assesses that Ukraine’s environmental protection legislation currently meets only the bare minimum of standards compliance. How would you evaluate the country’s European integration process when it comes to environmental law?

In my view, there’s no interest in this on the part of the government. We hear a lot of declarations, a lot of pretty phrases, but in reality no one in the government is working on integration. And now it turns out that the Minister of the Environment and Natural Resources (Ruslan Strelets) is claiming that in the environmental sphere Ukraine is 63% integrated, while the EU assesses our efforts at one out of five.

How can Ukraine bring its legislation into full compliance with the European Union under the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU in just a few years? For example, an Emerald Network was supposed to have been created at the legislative level in Ukraine by 2019. This will be a network of nature protection areas along the lines of the EU’s NATURA 2000, protecting vulnerable plants, animals, and their habitats in the region. Yet it is already 2023, and the relevant law has not even passed its first reading. The Ministry wants to get the job done, but the law faces opposition from numerous parties, including foresters, farmers, hunters, and the mining industry.

Another case in point is the obligatory adoption of a whole legislative package regulating invasive species under EU rules – on which work has not even begun. There are a few rare exceptions – for example, in the form of a list of non-indigenous species of trees that are forbidden for use in forestry.

Have you noticed a change in the formats, focus, or funding for environmental organizations recently?

Many organizations or individual activists are focusing on the impact of military activities on nature, and on the challenges of rebuilding the country. Correspondingly, they are paying less attention to “traditional” problems. For example, our organization has devoted a lot of time and effort to helping protected areas that have suffered from the Russian invasion.

In addition, many activists have emigrated, either internally or beyond Ukraine’s borders. Many are serving on the front lines, which, of course, doesn’t make our movement’s activities any more effective.

As for financing, unfortunately very few people are making donations to environmental organizations at present. For most the priority is still to support the army. But in any case donations were often not the main source of funding for environmental organizations. Perhaps this will change after the war: the culture of supporting social initiatives has grown significantly over the last year.

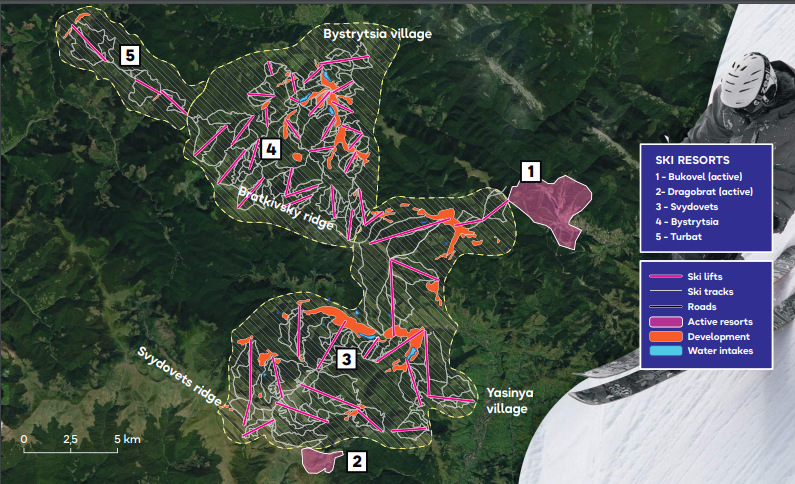

But it’s very pleasing that most of the activists who continue to work are finding the strength to support “pre-war” issues, often on a voluntary basis. An example could be the Free Svydovets movement, in which I’m also participating. Its aim is to protect the Svydovets mountain range – one of the best-preserved ranges in Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountains – from development.

This year the Free Svydovets initiative got a lot of media publicity in Ukraine. The plans to develop the Svydovets range were announced quite a long time ago, so why has this become a hot issue only now?

That’s true. The Free Svydovets movement began sometime in 2016, which was when civil society first learned of Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky’s plans to build a ski resort at Svydovets.

Before the full-scale invasion, there was a drawn-out legal challenge on the issue in the courts: local residents and NGOs were suing the district authorities, which were acting as the nominal representative for the resort project on behalf of Ihor Kolomoisky. The defense has now become more active in the courts, anticipating that Free Svydovets activists will be otherwise occupied while the country is at war.

Another argument for lobbyists is the fact that the country’s borders are currently closed for men. In peacetime, the majority of the able-bodied population in the Carpathian region went to work in Europe. Now that this possibility no longer exists, jobs need to be created in rural communities, and they see the resort as a great opportunity.

How did you manage to put together and promote a media campaign in such a difficult time for the country?

Free Svydovets is a movement in which a lot of people are involved – the success of the media campaign is also down to them. Our initiative is also supported by the European Parliament: their reports on Ukraine mention the project.

In the last few months we’ve been trying to get the Svydovets story highlighted in the media. For example, we’ve created a petition to President Zelinskyy with a request to ban construction at Svydovets. As a result, it collected the required number of signatures (25,000), and the issue was also widely covered in the media.

Many media outlets have picked up on the topic – even people’s deputies have written articles about the problem, highlighting the risks of building a resort. At some point, the authorities will have to make a decision for or against the project – the more they talk about the problem of Svydovets, the more difficult it will be for the ministry to greenlight the project.

As for next steps, we’re planning to create a nature refuge at Svydovets. Working alongside several other organizations, including the international NGO Environment People Law and WWF Ukraine, we have prepared a package of documents and are beginning to cooperate with government agencies with the aim of creating a protected area. Unfortunately, the authorities remain silent at the national level.

In parallel with this, other activists from the Free Svydovets movement are now actively participating in legal proceedings.

On the whole, we feel positive. As one of my university teachers once said: “The effectiveness of nature conservation should be measured by the answer to the question ‘Has the life of the hedgehog improved as a result of this?’” The life of a hedgehog at Svydovets has not yet changed. But we are gradually getting closer.

You can follow the Free Svydovets initiative on Instagram or on their website: https://freesvydovets.org/

Find out more about the work being done by Yehor and his colleagues on the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group’s website.

Comments on “Protecting the environment in times of war: An interview with environmentalist Yehor Hrynyk”