Yuliia Spinova

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has sharply altered the contours of life for the whole country. While all living beings in Ukraine are in danger, animals’ chances of survival in wartime conditions differ drastically, whether for wild animals in their natural environment or for those in human care in zoos, animal shelters and rehabilitation centers. UWEC Work Group has already published articles about the impact of military action on rare small mammals, abandoned pets and farm animals, on seals and other sea creatures (1, 2, 3), as well as the consequences of the war for animals living in protected areas (1, 2, 3). This article deals with the survival of those animals whose everyday life depends entirely on humankind.

Over the last year, the IUCN Species Survival Commission has regularly noted the important role of zoos and botanical gardens in the conservation of biodiversity and even published a corresponding declaration. Today’s zoos, with their modern technologies and zoological databases, are a powerful tool for supporting the population of many animal species, as well as for the preservation of several species that have died out and disappeared in the wild. However, war has always led to huge losses for zoos, and sometimes even to the complete annihilation of their animals.

Zoos and the wars of the past

During the First and Second World War, zoos experienced severe difficulties, affecting their operation, their financing and social attitudes towards animals. Many zoos lost animals during these wars due to a lack of resources, bombing and evacuation. Animals in captivity were under threat not only because of the conditions in which they were kept and their complete dependence upon human beings, but also as a result of changes in social priorities, when military needs took priority over everything else.

London Zoo and the move to Whipsnade

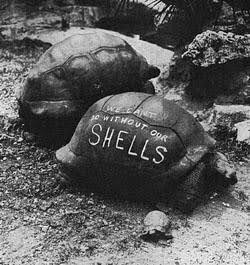

The archives of London Zoo show that at the beginning of World War II the zoo was already preparing for possible bombing, since in September 1939 some of the zoo’s animals were transferred for protection to Whipsnade Park Zoo, located in a village 55 km northwest of London. These included two large pandas (one of them, Ming, was the first large panda to appear in a European zoo), two orangutans, four chimpanzees (which subsequently escaped from the island where they were resettled), three Asian elephants and an ostrich. All the zoo’s poisonous animals were killed, in order to prevent them from escaping if the zoo was bombed. Some reptiles were saved, however, including a Komodo dragon and Chinese alligators. Additionally, two large wooden shelters – 7.6 and 8.5 metres long – were constructed to house two enormous pythons.

During the war the zoo was hit by bombs on numerous occasions. Sometimes these raids left little but broken glass, while in other cases entire buildings were destroyed. One of those days was 27 September 1940. Several high-explosive bombs hit the zoo, damaging the buildings where the zebras, rodents and civets were housed, along with the gardener’s office and all breeding areas. Miraculously, not a single animal suffered, although a zebra and a wild donkey with a foal escaped (the zebra was later found). Thirty-five incendiary bombs fell on the zoo that night, and following the discovery of an unexploded bomb the complex was closed for more than a week.

The first Christmas of the war was a sad one for the zoo, especially after the death of a black rhino that had been evacuated from London. Later an African elephant also died. Their bodies were cremated. But this was the last time that dead animals were burned – from then onward, they were used as feed for carnivorous animals.

When in 1940 the German-Italian-Japanese alliance was named Axis, the zoo began to refer to axis deer (Axis axis) simply as “spotted deer.”

The war was a difficult ordeal for the animals. When heavy snow fell on the zoo, one panda and tiger cubs went into convulsions. With the beginning of fuel rationing, the number of visitors dwindled, meaning the zoo had less money to spend on feed. Visitors were initially encouraged to bring lettuce leaves, cabbage and carrots with them, but soon nobody even had this to spare. The zoo began to grow its own mealworms to feed the birds, and fed meat covered in fish fat to those animals that usually consumed fish.

A colony of bright green noisy parrots, originally from South America, lived in an enormous common nest above the zoo’s main entrance gate. Once they were even bold enough to descend and wreck a nearby orchard. The following year they were kept in a cage until its apple harvest had been gathered.

The signal that traditionally announced closing time at five o’clock, which sounded from a high water tower, now served as an air-raid siren. According to the testimony of local inhabitants, it was always accompanied by the baying of the zoo’s wolves, which created a somewhat creepy atmosphere.

Over 40 bombs were dropped in the vicinity of the zoo in 1940. Most of these fell on the park, forming large hollows, which later turned into ponds. However, these bombardments also claimed victims: a spur-winged goose (Plectropterus gambensis) – the zoo’s oldest resident – and a baby giraffe.

Berlin Zoo

Berlin Zoo also suffered badly from military action in World War II, with many bombs falling on the complex. During the fight for Berlin, the zoo became a battlefield, and tanks and shells left their destructive mark. The condition of the park, which had once been so popular with visitors, gradually worsened and by the end of the war it was riddled with craters and littered with dead soldiers and the corpses of animals. Of a population of around 3,500 animals, fewer than 100 survived.

Warsaw Zoo

Warsaw Zoo came under regular shellfire in September 1939, and many animals died as a result of either bombs and bullets (anthropoid primates) or missiles (an elephant and a giraffe). After Warsaw’s surrender, the Nazis transferred most of the animal species to the Schorfheide nature reserve in Germany, while others, described at the time as being of “no value”, were shot, and the zoo was closed. After its director Jan Żabiński was released from captivity, the animals were gradually shipped back to the zoo, though it only reopened in 1949.

Belfast Zoo

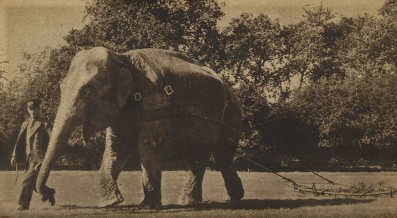

During the Blitz in 1941, the Luftwaffe also bombed the zoo in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Twenty-three of the animals in Belfast Zoo (including six wolves, two polar bears, a hyena, a tiger, a puma and a black bear) were shot by members of the Royal Ulster Police on orders of the Home Office, which was concerned that the animals would escape as a result of a bombing raid. In one particularly famous episode, which was later even adapted into a film, a local woman saved a young elephant. Denise Austin, one of the zoo’s first keepers, decided to ensure the safety of an elephant calf named Sheila by taking her out of the zoo every evening and bringing her home.

Ukraine’s zoos also suffered during World War II. On September 19, 1941 the Red Army retreated from Kyiv and two days later the fascist occupation began. On September 24, explosives left by Soviet sappers almost completely destroyed a number of the city’s central streets (including Kreshchatyk and today’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti, among others). The blasts disabled the city’s utility networks.

At the beginning of the war, Kyiv Zoo could boast 155 mammals and 796 birds, a three-year-old zebra and bears aged from seven to 15 years old. In his report to the city administration dated October 18, 1941, the zoo’s director Ivan Chernyakhivsky noted that the general condition of the animal was satisfactory, with the exception of those subject to culling. However, the lack of bread, sugar, and bulk feed had a negative effect on their health.

In addition, in the very first few days after their entry into Kyiv the Germans began to remove animals, feed, equipment, special clothing and coal from the zoo, reasoning that the animals would die in any case.

Ukraine’s zoos in times of tumult

Today there are 13 zoos in Ukraine that are protected areas, of which seven are of national importance and five are of regional importance.

Kyiv Zoo

In 2022, Kyiv State Zoo found itself in completely new circumstances following Russia’s full-fledged invasion of Ukraine.

According to estimates by Kyiv authorities, air-raid sirens sounded in the capital 638 times in 2022. These states of alert lasted a total of almost 700 hours, meaning that Kyivans, including the staff of the zoo, spent nearly 29 days – an entire month – in basements and bomb shelters.

When fighting began in the Kyiv region, 16 of the zoo’s staff immediately joined the ranks of the territorial defense forces, and later the Ukrainian army. Shelters were set up in the zoo’s basements, and to this day, animals are transferred from their outdoor enclosures and locked in indoor premises during air raids.

One sad example of direct losses among the zoo’s bird population as a result of military action concerns pink pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus), which destroyed their own eggs, and, accordingly, their lack of offspring in 2022.

The significant increase in noise (sirens, explosions and gunshots) and vibration pollution also led to the disruption of the natural course of hibernation in the zoo’s bats. Their failure to reproduce in the spring is probably also associated with the stress experienced by the females.

A similar “malfunction” also occurred with the zoo’s lemurs, with one female abandoning her cub. The young lemur was then artificially fed by veterinarians, who gave it the timely name of Bayraktar (the name of the Turkish-made drones widely used by Ukraine).

In the first two and a half years of the full-scale Russian invasion, staff at Kyiv Zoo took more than 500 animals from other locations into care. They were all registered in the ZIMS Species360 database, the world’s first integrated global real-time database of animals in zoos and aquariums. The list includes animals evacuated from combat zones (the Kyiv, Kharkiv and Kherson regions); animals received from private individuals who were unable to care for their “favorites” due to power outages after missile strikes on energy infrastructure; wild animals confiscated by the Ukrainian police on suspicion of being illegally traded; and bats received from people for rehabilitation.

Some of the first animals to be turned over to the zoo were a roe deer and an owl. The zoo’s veterinary doctors fought for days on end to save the life of the deer, whose body was covered with severe burns, but unfortunately it died. The owl, which had lost its sight as a result of an explosion at close quarters, was given the necessary treatment and it still lives in one of the bird enclosures.

Kyiv Zoo acknowledged these losses, but continues to endure these difficult times with dignity. As Ukraine began experiencing problems with electrical and heating supply as a result of Russian attacks on its critical infrastructure, the zoo purchased electric generators using charitable donations.

Kyiv Zoo has received over 70 metric tons of feed and veterinary medicaments as humanitarian aid from zoos and partner organizations of the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA), as well as selected international charities and peace foundations.

Kharkiv Zoo

Kharkiv Zoo in its more than 125-year history has also endured many difficulties: the civil war, when it survived the red Bolshevik terror, the rampage of Anton Denikin’s White Guard, the consequences of the intervention; World War II, when the zoo changed hands twice; and the 1990s, when the city’s residents saved the animals from starvation.

On February 24, 2022, Kharkiv residents were awoken by a vague rumble and distant muffled explosions. By midday, Russian motorized infantry had occupied the northeastern outskirts of the city. Enemy artillery was destroying residential buildings. From this point onward, it became very dangerous to move around the city. The zoo’s staff and their families, many of whose homes were left in ruins, moved to the zoo. The wife of one of the staff even gave birth in the zoo.

The zoo has had to accept a total of 46 animals from private collections, which could not be saved due to the war.

The disruptions of the first days were smoothed over by a two-week supply of feed. Later, volunteers were of great assistance, bringing food not only for the animals but also for the zoo’s staff. Power cuts were the biggest concern, since a large number of electric fences had appeared in the zoo following reconstruction work, most of the gates (partitions between the sections of the enclosures) ran on electric motors. Without electricity it also became impossible to supply and filter water, heat buildings, and much more.

The animals reacted calmly to these changes and were bothered little by distant blasts. Only when explosions resounded close by and the shockwave smashed glass and broke open gates did they become frightened. The monkeys reacted the most acutely, running for shelter with loud screams.

Cherkasy Zoo

In a situation when all regions were being hit by missile strikes, it was unclear how quickly the war would reach specific cities. Cherkasy Zoo continued to operate normally on February 24-25, 2022, only closing to the public on the 26th.

In the first year of the full-scale war 70 new animals were transferred to the zoo for care.

In view of the new realities, the zoo developed an action plan in case of missile strikes. For the protection of animals, zoo staff and visitors, the decision was taken to lock the larger animals inside buildings.

Odesa Zoo

Odesa Zoo was closed to the public for a whole month from the first day of the full-scale invasion (February 24, 2022). Fortunately, the grounds of the zoo were not damaged by shelling, so the animals did not suffer physically. Nonetheless, all personnel had to adjust to a new work schedule, to ensure that some of the specialists were on duty around the clock.

The biggest problem for the zoo was the huge wave of animals – mainly pets – which local residents began bringing in during evacuations. Around 700 individuals (birds, rodents, reptiles, fish, spiders, scorpions and mollusks) have moved to the zoo either permanently or temporarily.

In April 2022 the zoo appealed to Odesans for help preparing the grounds for the zoo’s 100th anniversary. The idea was to give the city’s residents a moral boost. The results exceeded all expectations – the initiative gave birth to a genuine volunteer movement, in which around 100 people took part over a three-month period. People came in families, in teams from various organizations, local residents and the internally displaced alike.

In these years of war Odesa Zoo has saved a total of 1,700 animals, of which 1,400 were pets and 300 were wild. In 2023 alone it received 1,000 birds and 100 animals.

Mykolaiv Zoo

Mykolaiv Zoo lived through eight bombardments during the first six months of the full-scale invasion.

“We were faced with the question of evacuating the animals, which we were completely unprepared for,” recalls the zoo’s director Vladimir Topchyy of the early days of the invasion. “Until mid-March the city of Mykolaiv was in semi-encirclement. There was one road left out – toward Odesa – and it was overloaded with transport. At night the bridges opened. The freezing weather lasted until the end of March“.

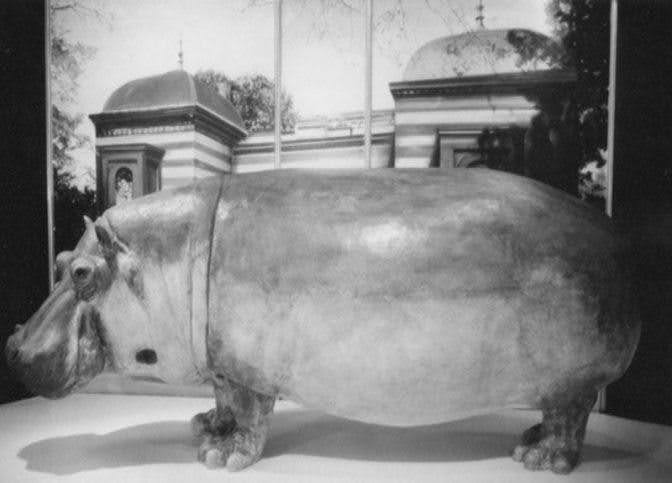

“We didn’t have enough transport cages, and we needed more than 400. We also needed transport. And during transportation the animals needed to be accompanied, fed and cleaned up after. The question of where to take the animals also hadn’t been resolved. Where could we accommodate them so they wouldn’t die? It seemed impossible to solve this complex logistical challenge. To move out the elephants, giraffes, hippopotamuses, primates, tropical birds, polar bears, tigers, lions, leopards… We decided against evacuation, since this had already been done during World War II. And we stayed with our animals, and they with us.”

The zoo opened charitable accounts in euros, dollars, Swiss francs, Czech crowns, Polish zloty, British pounds and Japanese yen. People from all over the world donated money to the zoo by purchasing “virtual” tickets.

Rivne zoo

On 24 February, 2022 the zoo received an order to restrict the presence not only of visitors but also employees. The zoo was closed, and the number of employees was reduced to the minimum necessary to ensure the care of the animals.

A temporary shelter was set up in the administrative building, and a supply of water, medicine and fire-fighting equipment was organized. Zoo staff provided active assistance in setting up a checkpoint near the zoo on the road leading out of the city.

Rivne Zoo, which is located in a relatively peaceful western region, received a great deal of requests to accept evacuated animals from other parts of the country. A large number of internally displaced citizens from regions which had suffered severely from military action also came to Rivne. Over time, there was a growing need to open the zoo to visitors, which in turn required expanding and increasing the size of the above-mentioned shelter.

A landmark event was a round table discussion on the topic of “Modern realities of Ukraine’s zoos in wartime,” planned to coincide with the zoo’s 40th anniversary and held on August 4-5, 2022, despite the country being at war. The leaders and employees of 14 zoological institutions gathered to discuss the problems that zoos were facing during the invasion.

Mena Zoo (Chernihiv region)

Hundreds of animals live at Mena Zoo: lions, camels, pelicans, bears. In 2022, on the first day of the war, tanks entered neighboring villages, preventing some zoo staff from going to work. As a result, the director and finance team had to care for the animals and clean cages during the early period of the invasion.

After the bridges were blown and there was no longer any Russian equipment on the streets, people began to return to work. The zoo then turned to local residents for help, who began to share what they could. In just one week the zoo received donations of money and food for at least the next six months.

The town of Mena was not shelled, but tanks drove through, planes hummed in the sky, and explosions and artillery salvos could be heard nearby. Animals are very sensitive to powerful sonic impacts, so these sounds of war frightened them. “Even now, they rush around the enclosure during the sirens, especially the bears. We have to open the dens. Everyone wants peace,” said Zinaida Maksimenko, director of Mena Zoo.

For obvious reasons, Mena Zoo has even altered the sign over its entrance, replacing the Latin ‘z’ with the Cyrillic ‘з’. Source: 0462.ua

Aid for zoos

In the first days of the war in Ukraine, two coordination centers were set up in neighboring Poland. These were engaged in providing feed and veterinary drugs for animals from affected zoos. Zoological institutions and private individuals in Europe and around the world provided enormous assistance during the first year of the full-scale war.

EAZA subsequently established a separate fund in support of Ukraine’s zoos called the EAZA Ukraine Zoos Emergency Fund, which continues its work to date. Anybody can donate to the fund, and can also support each zoo individually by visiting them or purchasing charity tickets on the website.

Why support is crucial

In comparison with past wars, the modern methods of waging war as practiced by the armies of Russia and Ukraine are rather different. While in the past all aerial attacks were carried out by means of direct shelling and bombardment from aircraft, nowadays missiles of various types and range are used, as well as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV ), usually referred to as drones. On the whole, we are observing a significantly larger number of cases of indirect damage and negative consequences for zoos and their inhabitants: the destruction of logistics and corresponding problems with deliveries of feed and the movement of zookeepers, which can affect the conditions in which animals are kept. These can all cause stress in animals and, as a result, psychological and behavioral changes.

Another distinguishing feature of a zoo’s work amid the ongoing war is the care given to animals from outside the zoo – both pets, whose owners or volunteers bring them in themselves (in the case of abandoned animals) and wild animals (from other, destroyed zoos, or which have suffered from military action in their natural habitats).

There are two sides to this situation. On one hand, this can be seen as evidence of a higher level of environmental awareness and humanity (environmental ethics has developed significantly over the past decades compared to the beginning of the last century). On the other hand, this causes a problem for zoos, since they are forced to accept additional animals onto their balance sheet, animals that often arrive with unknown background and origin and which are kept in less comfortable conditions than those prescribed by today’s high modern standards for animal husbandry.

Another question concerns the evacuation of zoo animals during a war in the country. This is an issue that is not raised by zoos located some distance away from the frontline areas or combat zones. As is clear from the historical record, evacuation was a common occurrence in past wars. But in those times there were far fewer animals in zoos than today. And, as has been said above, the priority is now the wellbeing of the animals, which, in the case of their transportation, means finding vast resources – transport containers/mobile cages, transport (which for some species needs to be specially designed), accompanying personnel (keepers and veterinary doctors) – which no zoo possesses. In addition, in cases when animals are shipped abroad, it is necessary to find places for each of them in advance in European zoos that provide suitable conditions for temporary care.

The war has hindered the active development of most of Ukraine’s state zoos, although some of them have now gained new cognizance of their goals and a push in the right direction. For zoos to continue to serve their main functions (conservational, scientific, environmental and educational) in wartime conditions, financial and humanitarian support remains critically important.

Translated by Alastair Gill

Main image source: irishexaminer.com