Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Viktoria Hubareva

Most of Ukraine’s protected natural areas have been damaged by the war and have now been deprived of their environmental value, although nature is showing a striking ability to spontaneously recover in belligerent landscapes. So what is the potential for the preservation and recovery of ecosystems and biodiversity in these areas?

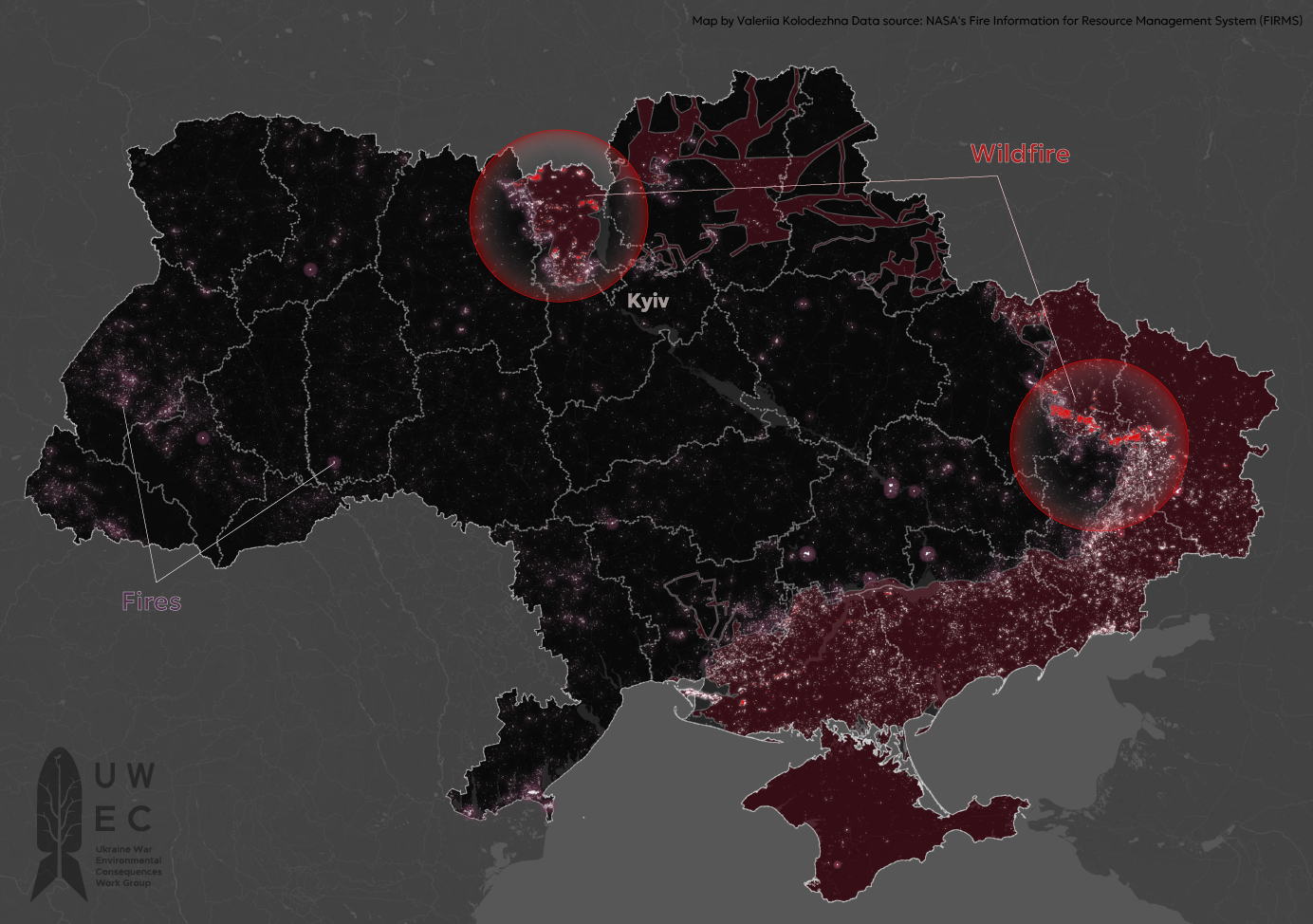

UWEC has already covered the subject of rewilding and post-war recovery, including the surprising recovery of nature on the site of the former Kakhovka Reservoir on the Dnipro River and the Oskil Reservoir on the Oskil River, where the dams were blown up for military purposes. We have also featured the recovery of the valley of the Irpin River in Kyiv Oblast, after it was flooded by water from the Kyiv Reservoir back in the very first days of the full-scale Russian invasion.

The recovery of these and other territories and ecosystem services will be the primary task once the war ends. However, there are also plenty of cases in which the renewal of ecosystems begins completely spontaneously.

What does war-wilding mean for Ukraine and what potential does it have?

Despite the colossal damage inflicted on ecosystems, species have shown an astonishing ability to return to damaged areas. The concept of war-wilding, introduced in 2022, is a very apt description of this process. Large-scale military impacts on the landscape create unique conditions in which people abandon territory for an extended period, leaving nature the chance for spontaneous recovery. We are not saying that this is a positive process, since after all it inflicts suffering on protected conservation areas and causes irreversible destruction and colossal losses. In addition, the vegetation that appears on fields and in settlements riddled with craters and shell damage is predominantly made up of invasive species, the spread of which is highly undesirable. However, spontaneous recovery in places where ecocide has taken place is today’s reality.

Good examples of war-wilding include the recovery of natural ecosystems on the site of the former Kakhovka Reservoir and the mass overgrowth of damaged territory along the frontline. The fact that many of these areas are heavily mined will ensure that huge tracts of land will continue to have the status of spontaneous recovery zones long after the war’s conclusion. Essentially, this means that there will be millions of hectares of land where it will be impossible to influence the processes underway in local ecosystems in the coming decades.

But there is also a positive side to this issue. Given the right circumstances, Ukraine’s abandoned territories, which in the coming decades will be economically useless, can help Ukraine or Europe as a whole to achieve environmental goals, which until now had seemed pretty distant and unrealistic. If spontaneous natural recovery processes for vegetation are given proper support from sponsors, we will have a world-class modern environmental conservation project. And this is just one of the scenarios that will be discussed down the line.

Scenarios of this kind are possible all over Ukraine, given the number of international obligations we have taken upon ourselves, signing up to a multitude of conventions, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Berne Convention, the Association Agreement with the EU, etc.

Where is spontaneous recovery taking place and what needs to be done for it to continue?

Many of the international pacts, plans, and conventions that Ukraine has joined, and which aim to improve biodiversity and conserve ecosystems, have set goals to be achieved by 2030. Reaching these targets requires nature restoration on an unprecedented scale in areas where it has already been lost or degraded (most of these areas are now used for agriculture). Making decisions of this scale would be a challenge for any country, and the right to private ownership of land will prevent such goals from being reached in millions of individual cases. However, such difficult and unpopular reforms must still go ahead for the sake of a sustainable future, and developed countries understand this.

Objectively speaking, the only place in Europe where we can see large-scale recovery of nature is the part of Ukraine which has suffered from military action. Despite much of the land being privately owned, having a designated purpose or being subject to other legal circumstances, vast areas will remain contaminated and mined for many decades after the war, unavailable for a return to their usual economic use. Until the hypothetical return of agricultural activity on these territories in the distant future, nature will continue to recover and flourish here.

Of course, this scenario should be considered, since nature will recover whether conceptual decisions are made or not, and this process is already under way. However, significant changes in legislation will have to be made to “legalize” spontaneous natural processes, and funds will probably have to be sought to compensate landowners. These could be sourced from Russian reparations or European environmental programs. But the effective and sustainable restoration of nature will only be possible with proper legal protection.

It is important to note that in the majority of cases forests are expected to recover (within river valleys local species will dominate, while alien tree species will appear on abandoned fields and in settlements). For now it is hard to assess the total area of “spontaneous recovery” but it can be expected to cover no less than 20-30,000 square kilometers. This natural recovery on territories lost to the economy can be a mutually beneficial scenario for Ukraine and its Western partners, since the situation Ukraine has found itself in is actually the most convenient scenario for achieving European goals.

It is no less important to also look strategically at the fact that the steppe climate zone (in which the majority of the lands directly affected by the war are concentrated) is dominated by steppe ecosystems and it is precisely they that are most effective in carbon sequestration in this region. So environmental management will be important in planning nature restoration activities with the potential to facilitate the rapid replacement of spontaneous invasive vegetation with local species of steppe plants that effectively sequester carbon and restore soil fertility.

In southeast Ukraine there is already an innovative project by the environmentalist Oleksiy Burkovsky, who for several years already has been testing a methodology for restoring steppe ecosystems on a site specially removed from agricultural use for this purpose.

You could say that Burkovsky is growing steppe on his plot of land. This local experiment, which already looks like a clearly working model, can be scaled up in the future to restore natural vegetation over much larger areas. In the years to come it will also help the transition of southern Ukraine’s economy from destructive arable farming and irrigation to an ecologically established model of pasture livestock farming.

For other states it may be of potential benefit to compensate Ukraine financially for the loss of agricultural areas and support the recovery of nature in Ukrainian territory, while preserving the country’s economic status quo. In such conditions the presence of additional resources will enable Ukraine to establish a new, compact industrial sector and a system for resettlement in safe areas, and to leave areas damaged and contaminated during the war as spontaneous restoration zones.

Main image credit: Alex Klochkov

Comment on “Spontaneous recovery in wartime: How Ukraine can become a testing ground for unique environmental projects”