by Oleksii Vasyliuk

Translated by Alastair Gill

This article continues a series devoted to the consequences of the nine-year annexation of Crimea Peninsula by the Russian Federation. Read the first article here.The seizure of Crimea and the installation of Russian-controlled authorities took place in 2014 without obvious military action. For this reason, the environmental consequences of the annexation are also not particularly obvious. However, the change in Crimea’s political status and its separation from the system of Ukrainian state control and administration quickly led to unprecedented environmental disruption. The construction of the bridge and its accompanying highway have produced some of the most irrevocable changes on the peninsula.

By far the biggest changes to have taken place on the Crimean Peninsula during the years of Russian occupation are the construction of a bridge linking the Taman and Kerch peninsulas and construction of Tavrida Highway. The new route has opened up a land connection between Crimea and the Russian Federation.

The appearance of such pieces of infrastructure, built on a truly historic scale, led to many direct and indirect changes, from the physical destruction of enormous areas of natural land (including those with protected status) and the construction of infrastructure around the new highway to the rapid development of a network of quarries for mining building materials and facilities for processing them. The greatest threat, however, is the possible changes to the biodiversity and hydrological conditions in the Kerch Strait and the Sea of Azov as a whole.

The Crimean Bridge

The structure is a transport crossing over the Kerch Strait, consisting of two parallel bridges — a railroad bridge and a road bridge — connecting the Kerch and Taman peninsulas via Tuzla Island and Tuzlinskaya spit. The construction, opening, and commissioning of the bridge were marked by the issuing of numerous state awards, medals, and commemorative coins.

The bridge’s official opening took place on 15 May 2018, when its road section was unveiled to the public. The railroad section opened for passenger transport on 25 December 2019, and for freight transport on 30 June 2020.

According to Russian state media, the preliminary estimate for the project was projected to be 150 billion rubles (in 2014) for the construction of the bridge, 86 billion rubles for preparatory works and 51 billion rubles for the construction of approach roads. However, by the time the first stage of the bridge opened these costs had soared to around $4 billion.

Russia’s justification for such a colossal investment, it goes without saying, is principally of a geopolitical and military nature. This is clear not only from the vast scale of financing, but also from the approach to the development of peripheral infrastructure that has accompanied the project from the very beginning.

Analysts also note that the bridge’s configuration and basic dimensions were deliberately designed so as to cause maximum obstruction to shipping in the Kerch Strait and the Sea of Azov.

The main span is substantially shorter and lower than those of other bridges built around the world in recent decades, including Russian bridges. This limits the size of vessels that can enter Ukrainian ports in the Sea of Azov, and also makes it significantly easier for Russia to control access and close it off at any time. The road bridge sits unnecessarily low, so even smaller ships are unable to pass beneath its supports, but are forced instead to use the main channel. In building the Crimean Bridge, Russia gained full control over the entrance to the Sea of Azov. There are also several Ukrainian oil and gas fields on the Sea of Azov’s coastal shelf. Construction of the bridge across the Kerch Strait means that oil and gas rigs can no longer be towed out of the Sea of Azov, since their dimensions do not allow them to pass under the arch of the bridge. With a significant part of the Black and Azov seas now empty of ships from any states besides Russia, Moscow has used the area to hold large-scale military exercises, which have been one of the most destructive consequences of the Russian occupation for the area’s nature.

Fig. 3-4. Construction of the Crimean Bridge on Tuzla Island. Sources: Viktor Babkin-Altair Studio and KerchTV.

At the same time, this construction work has created a wide range of environmental and social threats that were not taken into account even at the design stage.

Construction of the bridge has significantly narrowed the Kerch Strait. As the map shows, a continuous bar of land around 5 km long has been reclaimed, extending from the Taman Peninsula to almost join up with Tuzla Island. In other words, land reclamation has essentially destroyed the island, which had extraordinary natural value: according to the application for the creation of a nature refuge on Tuzla Island, it was home to five species registered in the Red Book of Ukraine. On the Crimean side an embankment roughly 1.3 km in length has also been built, with another 5 km embankment approaching from the Taman side.

The blocking of the strait with these embankments has undoubtedly had an impact on hydrological processes in the passage as well as affected coastal currents and plankton migration. Unfortunately, it is impossible to study these changes remotely.

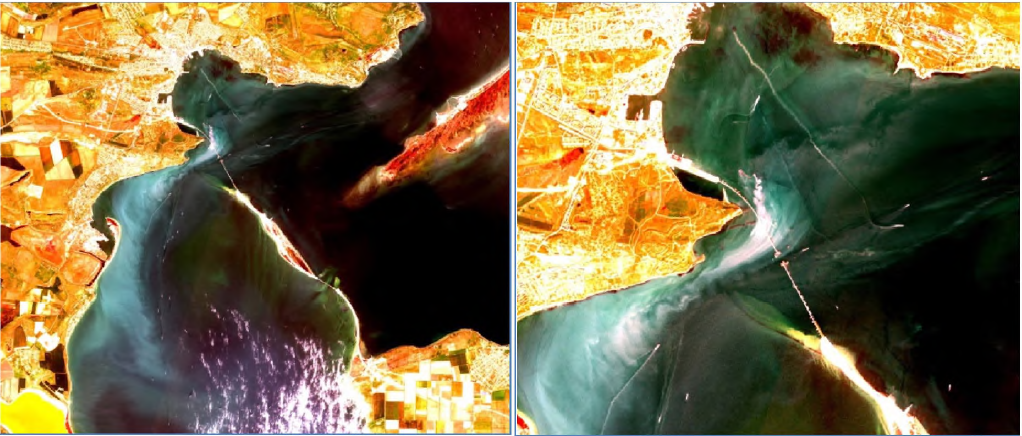

Fig. 5-6 – Tuzla Island as seen in satellite photographs from 2009 and 2019. Sources: Google Earth.

Conservation-related concerns on the Russian coastline were also ignored during the construction of the bridge, which was built on an internationally recognized bird area. In order to circumvent the environmental review procedure, the Russian parliament adopted a special law (No. 221-FZ, dated 12 July 2015) and introduced amendments to legislation on environmental reviews, land management and protected areas, as well as the Water and Land codices, since it was impossible to build a bridge here without breaking them all. This legislation, “fine-tuned” to the needs of the construction project, gave a green light for work to begin without the need to wait for any expert conclusions.

During construction, the Russian government announced that it would resettle rare animal and plant species from the construction zone. Photographs published to promote this “relocation” show students and schoolchildren in T-shirts reading “Institute of Economy and Land Use” — an institution which appears not to exist. A report on the publicized completion of the “relocation of frogs and snakes” was delivered to Putin in person (though the schoolchildren in the photo were pictured with plants in their hands).

Ironically, the rare fauna in the bridge construction zone includes dolphins, fish and crabs, as well as birds that fly over the strait. It is hard to imagine how these animals could be “relocated.”

Construction of the Crimean Bridge has resulted in a range of threats to the local environment, hazards that can already be substantiated without the need for laboratory studies.

Hydrology

In 2018, experts from the Moscow-based Institute of Water Problems prepared a detailed study of the impact of the construction of the Crimean Bridge on the unique hydrology of the Kerch Strait and the Sea of Azov. Over the course of the year, the water level, salinity, and current undergo significant seasonal fluctuations. In the summer the water temperature rises to 30 ∘С, while in the winter the sea can completely freeze over. As water exchange worsens, the water temperature will increase in the summer and drop in the winter, which will create substantially harsher ice conditions.

A study carried out in February 2017 using data from NASA showed that ice had already begun to drift out of the Sea of Azov in the first part of February, driven by northern winds. Consequently, in a matter of days the entire northern part of the strait was covered in ice, blocked as it was by the bridge.

Peculiarities in the bridge’s design mean that ice cannot pass between the supports and instead builds up instead. The bridge essentially replicates the effect of a dam. This serious threat has been highlighted by not only Ukrainian, but also Russian hydrologists. The buildup of ice will make the suffocation of fish in the Taman Bay a common event, and could also lead to the shoreline suffering damage from surging ice.

Fig. 7a-c. Rapid buildup of ice in the Kerch Strait in February 2017 (а – satellite image from SPOT 7 (AIRBUS Defence & Space) 09.02.2017; b – satellite image from SPOT 7 (AIRBUS Defence & Space) dated 11.02.2; c – Sentinel 2A (ESA) 13.02.2017). Source: Mykhailo Romashchenko.

As in all of the world’s shallow waters, rich and distinctive fauna have developed in the Sea of Azov, and a change in the seasonal dynamics of any of the factors listed above is very likely to be critical.

Given the thick layer of silt in the strait, clearly visible in satellite photographs, dredging was necessary before the pilings could be installed in order to remove silt from the target area. The action of driving bridge pilings into the sea bed also caused bottom sediments to rise into the water column.

Ukrainian academics from the Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas have pointed out that construction of the Crimean Bridge has polluted the waters with fine sand, which destroys fish eggs and plankton organisms. This is also happening near sand excavation sites on Lake Donuzlav and in the Karkinytska Gulf, which are also important fish spawning habitat.

Dolphins

The Sea of Azov is home to two species of dolphin. Both are rare species, registered in the Red Book of Ukraine and protected by the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and contiguous Atlantic area (ACCOBAMS). The Kerch Strait is one of 18 especially important zones for Mediterranean and Black Sea cetaceans.

Sea pollution caused by the transport corridor and changes to the migration routes of the fish on which dolphins feed have a negative effect on the activity of these mammals, and the constant noise from trains and vehicles on the bridge complicates their migration. There are serious concerns that sound pollution in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait resulting from sand extraction, construction of the bridge (the installation of pilings with pneumatic piledrivers), and traffic have been key factors in causing the deaths of dolphins. There have been no studies on cetacean deaths in the occupied territories. But experts specializing in the study of dolphins assert that since construction began on the Crimean Bridge there has been a significant increase in dolphin deaths.

Tavrida Highway

In addition to the bridge itself, the project also involved construction of road infrastructure totaling 250.75 km in length, linking it to the Crimean cities of Kerch, Simferopol, and Sevastopol. Construction of Tavrida Highway took place between May 2017 and August 2020.The highway project did not undergo environmental review. According to the Crimean “Ministry of the Environment”, this was unnecessary, since the highway did not pass through any territory of special natural value. Of course, this is not the sole reason for holding an environmental review: the purpose of such a review is also to certify that the construction site is safe and that the construction process presents no danger to the local population. Environmental issues aside, a whole host of other aspects were not taken into account, among them the fact that the new fenced highway isolated eight settlements with a total population of 12,000. Since no access roads were built onto the highway, these settlements ended up completely cut off from civilization.

Fig. 10-11. Construction of the highway was accompanied by the destruction of natural landscapes. Sources: Krymoved, Vesti Sevastopol.

Construction work on the highway began in the summer of 2017 on the Crimean side. The first high-profile incidents were the demolition of 80 residential buildings in the town and the Zaliv dacha housing cooperative and the routing of the highway through an ancient burial mound.

As construction continued to expand, it became clear that damage to the local environment would be significant. Unfortunately, the vast majority of news coverage at the time was devoted to the felling of windbreaks along existing roads widened to build the highway, though this was one of the less serious consequences. At the same time, the publicity given to this issue led to demonstrative statements from the Kremlin-controlled Crimean authorities and the Russian federal authorities, promising that windbreaks would be planted along the entire length of the highway.

Yet the media almost completely ignored the destruction of natural landscapes, including the rapid growth in the size and number of quarries. And no proper coverage was given to the large-scale deforestation that accompanied construction of the highway (the media kept quiet about places where intensive logging occurred, knowing the kind of unwelcome attention that even damage to windbreaks attracted).

The environmental ministry of the “Republic of Crimea” reported that it had issued permission for the felling of 133,849 trees and 121,749 bushes (it would be interesting to know who counted these “bushes”, and how) and that once the highway was finished, new trees would be planted along the road. This populist promise is easy to refute by analyzing the route followed by the Frontovoye-Inkermanska Dolina section of the highway, where it passes directly through forest, which led to the deforestation of 180 hectares (see. Fig. 7).

Fig. 12-13. Construction of Tavrida Highway in the vicinity of Frontovoye (coordinates 44.653873, 33.706005) as seen in satellite photographs (left – before construction began; right – after). Source: KrymSOS.

Here, the number of trees for which felling permission was supplied is at least 10-13 times greater than the forest section in question — the only designated forest area the road was to pass through. In other words, no one carried out any counts or removal of trees for felling, and thus none of the figures supplied by the Kremlin-installed authorities have any relation to reality.

The populist nature of this promise is also evident in a different regard: deforestation essentially took place only in the vicinity of Sevastopol, while the promise was to compensate for this by planting windbreaks in the flat Crimean steppe, through which the main part of the highway passes. Trees have almost no chance of surviving in this kind of landscape.

So in reality the logging was not offset as the Russian-installed authorities promised. And promises to plant trees in the Crimean steppe, the most arid territory in Ukraine, merely highlight the complete incompetence of those responsible for construction.

Fig. 14-15. Construction of the Tavrida Highway and excavation of a quarry of over 30 hectares beside it near the city of Kerch (coordinates: 45.316726, 36.393265) in satellite photographs (left – before the beginning of construction; right – after). Source: KrymSOS.

Mining of building materials for the ‘project of the century’

It was to be expected that Russia would make the most possible use of local resources for this giant building project. The inexpediency and costs of transporting such huge quantities of building materials from Russian territory, combined with Moscow’s purely strategic interest in Crimea, quickly led to extensive mining activity in different parts of the peninsula. Meanwhile, the Russian Ministry of Transport was actively promoting the enterprise, branding it the “Project of the Century.”

In the initial phase of the occupation, subsoil resources were extracted without permission, since there was no longer any need to acquire it from Ukraine. Despite the fact that the self-proclaimed Crimean authorities passed their own law “On subsoil resources” back in 2014, a year later the Russian parliament passed a federal law governing the legal regulation of the use of resources in Crimea, which handed full control over decision-making on Crimean subsoils to Russian federal authorities and Moscow’s local proxies. Because of this, it is impossible to determine who initiated the use of resources in any given situation.

One of the threats that attracted the most attention during the bridge’s construction was revealed in a remark by Yury Yuryev, a deputy in the Crimean parliament, who said that sand contaminated with waste from the chemical industry was used in the construction of facilities on the Kerch Peninsula. His conclusions were supported by results of the analysis of samples taken from waste at the Nizhne-Churbassky waste storage facility from the Komysh-Burun Iron Combine, an iron enrichment plant located on the Kerch Peninsula.

During the construction of the Crimean Bridge, sand was excavated from the embankment of a tailings dam. This is a massive earthen embankment around an open storage area for chemical and radiation waste that cannot be recycled. This excavation took place despite the fact that, according to industrial standards, even driving along the dam should have been prohibited.

Fig. 16-17. Excavation of sand from the Nizhne-Churbassky tailings dam in 2016. Sources: Crimea Gates, Kerchnettv.

Analysis of satellite photographs shows that the extraction of sand from the tailings dam began in the second half of 2014.

Fig. 18-19. Sand excavation from the tailings dam in satellite photographs from 2013 (left) and 2019 (right). Source: KrymSOS.

The problem is not only that chemically contaminated sand was used during construction, but also that significant rainfall may now wash waste from the tailings dam into the Black Sea in the immediate vicinity of the municipal beach of Kerch, a tourism destination.

In February 2018 the Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and Internally Displaced Persons of Ukraine reported that the amount of arsenic in that waste exceeded the maximum permissible concentration by 500 times, antimony levels by three times, vanadium by three and a half times, chromium by 1,420 times, and phosphorus and iron by 341 and 370 times, respectively. Analysis showed that the sand immediately bordering the waste has an arsenic concentration 377 times above the maximum permissible level. The concentration of dangerous compounds is lower inside the embankment, but is still 40 times over the maximum limit.

In May 2017 the local environmental prosecutor’s office prohibited the excavation of sand from the tailings dam. The territory was then just abandoned, leaving toxic sand to be freely dispersed by the wind. According to our estimates, over 600,000 cubic meters of sand had been removed by the time excavation work concluded at the site. Yet (as the above satellite images show) in 2019 excavation began again in eight places along the banks of the bypass canal of the tailings dam — just 50 meters from the previous excavation site.

Fig. 20-21. Sand removal from the bed and banks of the bypass channel of the tailings dam with the help of a dredger in 2019. Sources: Krym.realii, Mikhail Dneprovsky (LiveJournal nordstrim).

Satellite images show the presence of dredgers, which indicates that sand was being extracted not only from the banks of the canal (in these places the width of the canal increased substantially in the course of a year), but was also being scooped from the canal bed, thereby deepening it.

Although the prosecutor’s office and even the Russian secret services (FSB) appear to have taken an interest in the excavation at the tailings dam, the extraction of so much toxic sand just 50 meters from the dam did not arouse significant public concern, also because it wasn’t reported in local media, and investigations were shelved. Documents from the Russian-controlled Crimean prosecutor’s office are available online.

Fig. 22-23. Satellite images from 2018 (left) and 2019 (right) showing the results of sand extraction on the bypass channel of the tailing dump. Source: Krym.Realii, Mikhail Dneprovskiy (LiveJournal nordstrim)

Another area used for sand excavation was the Bakalska Spit. Located on the diametrically opposite side of the Crimean Peninsula, this spit is in fact part of a Crimean strict nature reserve (at present, Lebyazh’i Ostrova Reserve). Any form of subsoil resource extraction here is categorically forbidden. Although instances of sand excavation were recorded here before the occupation, large-scale removal of sand from the spit began with the construction of Tavrida Highway. Even major Russian state media warned that the spit was under threat of destruction, but excavation continued. An analysis of satellite photographs shows that Bakalska Spit has now vanished, leaving just a small island.

Quarries for excavating building materials began to appear in different parts of Crimea during construction of the bridge and the highway. While there are no official statistics for the number and total area of these quarries, there are now up to 260 of them on the peninsula. A significant number of them reopened or were opened when building work began on Tavrida Highway — crushed rock is an especially important resource for construction. The opening of the quarries was accompanied by protests by the local population, many of which were suppressed.

Conclusions

The Crimean Bridge was one of the largest construction projects in Russian history, but it was also one of the most dangerous for the surrounding environment. Changes to the hydrology of the Kerch Strait, the damage inflicted on the Crimean peninsula’s geology as a result of stone quarrying and sand excavation, and construction of the Tavrida Highway — have all permanently mutilated Crimea’s natural environment. If the bridge is destroyed, these threats will only grow. The hope is that once Ukrainian experts regain access to Crimean territory, a study of the environmental consequences of the annexation will be carried out, beginning with a detailed study of the threats described in this article.

Comments on “The Crimean Bridge: Environmental impact of Russia’s ‘project of the century’”