Compilation by Eugene Simonov and Oleksii Vasyliuk

Translated by Jennifer Castner

Ukraine’s path to Europe will undergo a comprehensive program for the country’s “green” recovery. UWEC Work Group concluded earlier that the plan presented in Lugano contains only a few scattered environmental measures (and many anti-environmental initiatives).

At the same time, the European Union is now adopting a law on the restoration of all ecosystems in Europe and is preparing to invest hundreds of millions of euros for the program’s implementation.

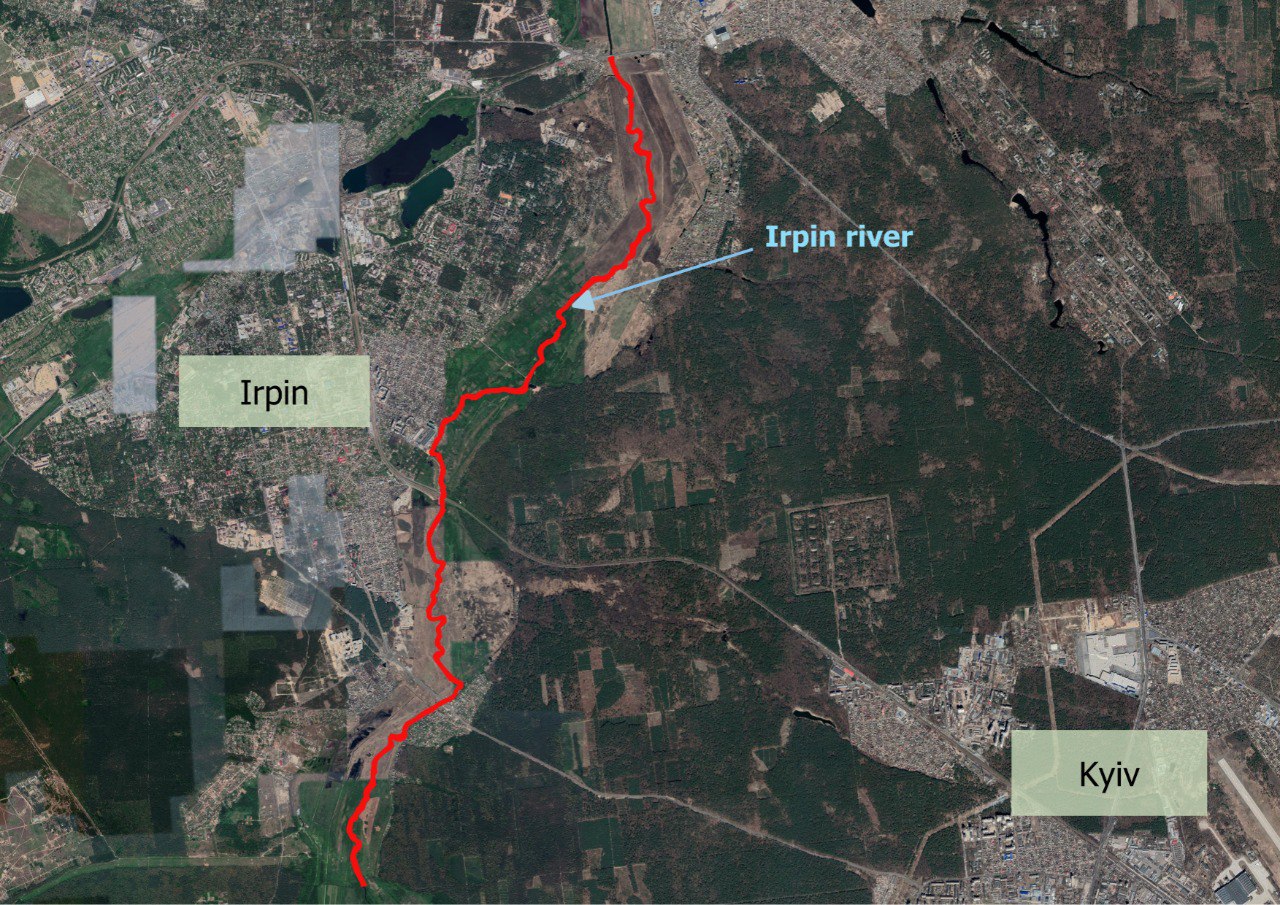

In this article, we will study approaches to restoring Ukraine’s ecosystems using the case of the Irpin River, a river which has rendered the country a huge service by blocking the enemy’s advance on Kyiv’s outskirts.

Unfortunately, public discussion of differing approaches to restoration of the Irpin floodplain have not yet taken place. Meanwhile, the way in which the fate of this heroic river will be decided could affect all subsequent decisions to restore the natural and economic potential of other war-affected river basins in Ukraine.

We have collected a range of opinions from various authors, experts, and environmental activists. The multitude and variety of their positions allows us to see the full spectrum of prospects for the Irpin’s restoration. We don’t offer a sole correct option, but rather believe presenting a variety of representations will make it possible to find the best solution.

Hydraulic war: History of the Irpin River’s role in defending Kyiv in 2022

On 26 February, at the very start of Russia’s invasion when Russian columns were en route to Kyiv, Ukrainian troops destroyed the bridge over the Irpin River near the village of Demydiv, a suburb of the Ukrainian capital.

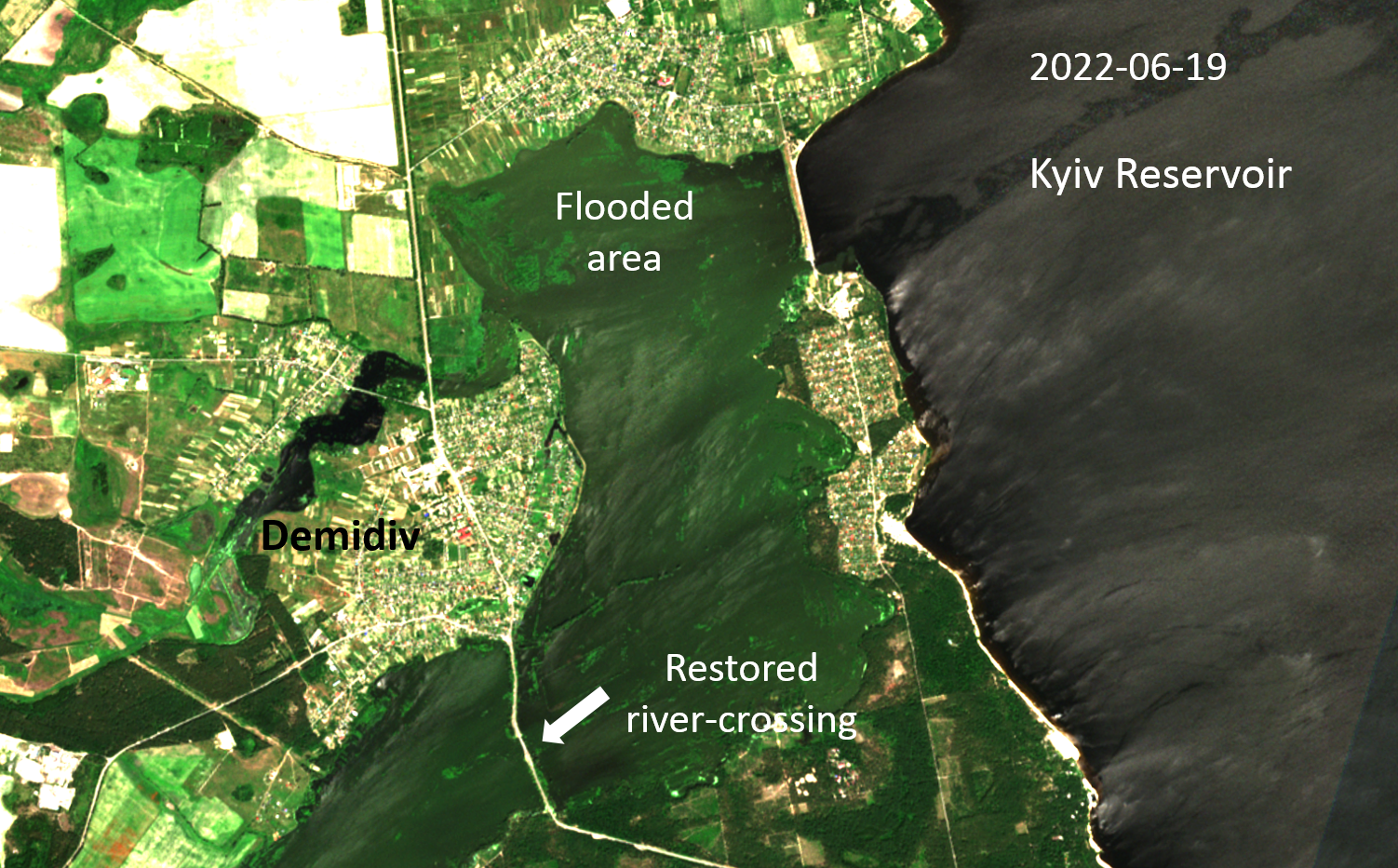

Faced with this challenge, the aggressor tried to break through Kozarovychi dam that protects the Irpin River’s reclaimed floodplain from being flooded by waters from the Kyiv reservoir. At that point, the Ukrainian military partially destroyed the dam separating the Irpin River from the Kyiv reservoir. The water that rushed into the river valley created a wide impregnable barrier against enemy troops and thus greatly facilitated Kyiv’s defense. 2,500 hectares of floodplain lands were engulfed, radically changing both the location’s ecology and Kyiv’s defense strategy overnight. Russian troops were unable to conduct a forced crossing of the floodplain wetlands and the entire offensive bogged down.

In the 1960s, when the Kyiv reservoir first gradually reached its full capacity (103 m above sea level), the floodplain of the Irpin’s lower reaches turned out to be three meters lower than the reservoir. The floodplain was protected from flooding by building both a protective dam and a pumping station that transferred water from the Irpin into the reservoir. Water is similarly pumped from other Dnipro River tributaries (Trubezh, Tyasmin, etc.) that share the same relative position.

In the first month and a half after the dam’s destruction, water from the reservoir flooded the Irpin floodplain for over 20 kilometers upstream. At its broadest, the Dnipro’s flooded tributary (near Demydiv) is two kilometers wide.

In Demydiv itself, the water came close to homes, but people courageously accepted this disaster, which also coincided with a temporary occupation by Russian troops. As of 7 April 2022 (40 days after the dam was destroyed), flooding reached the outskirts of Huta-Mezhyhirska, Chervone, Moshchun, Horenka, and Hostomel, flooding all the lands to a height of 103 meters above sea level.

Overnight, the Irpin River became the subject of worldwide discussion. Washington Post journalists marveled at the return of “hydraulic warfare” to Europe.

In the EUObserver, river and ecology experts recalled the dire humanitarian consequences of past dam failures, including the Dnipro Hydropower Station during World War II, and urged parties to the conflict to avoid destroying large dams.

The New York Times published a multimedia essay about life in the flooded villages freed from occupation. State Russian media used scare tactics almost daily, writing that “Ukrainian nationalists” are preparing to blow up another dam and that it will play out similarly to the Irpin.

In Ukraine, different assessments of the Irpin events were presented and often opposing views were expressed regarding future ways to deal with the river valley during the country’s “green recovery.”

The disputes continue today, and in order to come up with a balanced recovery plan, all stakeholders must be heard and experts be interviewed.

As far as UWEC Work Group can establish, the destroyed dam is currently being restored. This was inevitable, given that it is also transportation infrastructure important to local residents and for Kyiv and included in plans for the city’s defense. Its restoration is accompanied by a promise to pump water out of the river valley, the expediency of which is ambiguous, both from environmental and defense perspectives.

Outraged minister: Official position expressed in terms of damage

According to the Ecopolitika portal, Ukraine’s Minister of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Ruslan Strelets used his Facebook page to state that the destruction of the Irpin dam during hostilities caused enormous damage to the environment and population centers.

According to the minister, this led to the release of more than 117.5 million cubic meters of water from the Kyiv reservoir. Those floodwaters entered floodplain lands previously protected by the dam. Residential buildings, forests, and meadows in the Irpin floodplain were flooded. Strelets added that the amount of damage is almost 27.4 million hryvnia. According to the minister, those who suffered from the flood were still happy about it, because “a flood is better than life under Russia.”

Scientists seek to balance interests

Scientists from Ukraine’s National University of Bioresources and Nature Management – Doctor of Biological Sciences Vladimir Starodubtsev and Candidate of Agricultural Sciences Maryna Ladyka – shared their professional assessment of the situation on the Irpin River floodplain with UWEC Work Group.

They have studied these now flooded farmlands previously and use their article to reflect on ways to combine land restoration with nature conservation and improved farming efficiency.

In particular, they write:

The plans for Kyiv hydropower station and reservoir officially describe this agricultural facility as “Protecting the Irpin city floodplain.” 1.4 km in length, Kozarovychi dam and its associated pumping station protected these lands by pumping Irpin waters into the reservoir at a rate of over 60 cubic meters per second. Roughly 2,500 hectares of these protected lands were used mainly as pastures and hayfields. A network of drainage canals, partially silted and in need of dredging, facilitated reclamation of this land mass. These waterworks are also in need of repair. Groundwater in summer occurs mainly at a depth of 0.5-1.5 m.

The current ecological state of the area is clearly visible on Sentinel-2 satellite imagery as of 19 June 2022.

Even before the war, plans were afoot to update and renew the protective infrastructure for this floodplain, a fact that will facilitate attention returning to this project after the war is won.

Heated discussions between environmentalists and the business community about the expediency and extent of wetlands reclamation should be taken into account. Clearly there will no longer be such a dense network of drainage channels as originally built. But the protection of household plots and the buildings themselves of the inhabitants of Demydiv will, of course, be ensured. Much attention will also be drawn to optimizing the design and reducing operational costs of pump station between the Irpin River to the Kiev Reservoir.

It is quite obvious that there will no longer be such a dense network of drainage channels, but protection of household plots and residential buildings in Demydiv will, of course, be ensured. The need to optimize design and reduce pumping station operating costs from the Irpin River to the Kiev Reservoir is also an important focus.

Kyiv Environmental and Cultural Center (KECC) calls for creation of a memorial for nature

Volodymyr Boreyko, director of the Kyiv Environmental and Cultural Center, believes that the Irpin River should receive the title of “River-Hero” and become a military memorial.

KECC approached the Irpin City Council with a proposal to create a memorial to protect the river within Irpin city limits (15-km area begins 20 km upstream from the Kozarovychi dam, where flooding was only minor).

We call for approval of a decision to create the “River-Hero Irpin” local landscape refuge with a total area of 127.9 hectares located near the Irpin River on Irpin City Council lands in Buchansky District, Kyiv Oblast. A fragment of the Irpin River with a total length of 14,880 m would be protected, located where the river is roughly 10 m wide and includes two coastal protective strips 50 m wide. This territory is not divided into allotments, is not in private ownership, and is not suitable for agriculture.

The conservation site consists of the Irpin River and associated protective strips along its banks and is an important element for maintaining the hydrological regime of surrounding natural complexes. It is valuable habitat for rare plant species and is also used for recreation.

In addition, the Irpin River is of great historical importance as a site for Kyiv’s defense over the last 1,000 years. Enemy infantry and cavalry struggled to cross the Irpin River’s wide wetland valley that repeatedly defended ancient Kyiv. In the late 1930s, Kyiv’s first line of defense was created along the Irpin River, with fortified emplacements built along the higher right bank. On 11 July 1941, units of the 13th German Panzer Division became bogged down in the valley wetlands and were partially destroyed by Soviet artillery. The Irpin’s strategic and tactical importance has been proven once again today, when Kyiv’s defenders blew up a bridge over the river and destroyed a pontoon bridge built by Putin’s troops. As a result, enemy troops were stranded in the flooded and swampy valley of the “savior-river” that has defended Kyiv for thousands of years. A site schematic, justification, and sample agreement for the landscape reserve prepared by Makarovsky Village Council are attached.

Respectfully,

Volodymyr Boreyko, Honored Conservationist of Ukraine, Director of KECC

In response to our question about the protection and restoration regimes for floodplain ecosystems, Vladimir Boreyko replied, We are not talking about periodic flooding of this area’s floodplain, but we are talking about ending the possibility of developing this part of the floodplain. Creating a reserve is the only thing we can do to protect the currently intact section of the floodplain and river.

Local experts advocate for creating wetland-based economy

Michael Succow Stiftung representative Olga Denyshchyk, an Irpin wetlands expert, shared her vision for the Irpin River. Her position is to preserve the wetlands by integrating them into suburban Kyiv’s “green economy.” Protection and expansion of the Irpin River floodplain’s ecosystem services will allow Ukraine to quickly achieve carbon neutrality obligations and achieve climate policy goals.

«Ukraine has signed the Paris agreement, promising to be carbon neutral by 2050. In part, this means that, like other signatory nations, Ukraine plans to restore and re-wet all drained peatlands – the most effective natural means of carbon storage.

In the past, the Irpin River’s floodplains stretched over 10,000 ha of peatlands, the deepest such deposits in the Kyiv area. After these peatlands were drained for agricultural use in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the river itself was straightened and its floodplains destroyed. Until recently, peat fires were very common in the area, resulting in air pollution. The media has reported on illegal peat extraction as well.

Current flooding could be seen as an opportunity to rethink Irpin River management and restore the river and its wetlands. Positive results will include, but are not limited to ending peat fires, more water in the river, cleaner river water, cooling effects for the local climate, returning and increasing wildlife populations, and largely natural recreation zones. Last, but not least, the floodplain will serve as a fortification barrier on the road to Kyiv. All these changes will boost community initiatives, including local businesses.

Possible options include not only environmental restoration, work that is costly and not possible in all parts of the territory. Severely degraded peatlands could be re-wetted and used for paludiculture (peat cultivation and forestry on rewetted peatlands) to produce insulation materials and biofuels that will be in high demand in Ukraine. It is possible to create a mosaic landscape of natural, semi-natural, and industrial and agricultural areas to benefit local communities, wetlands, and climate.

Sadly, current floodplain management near the town of Irpin includes plans for construction of a new residential complex. Aside from environmental damage to the river, these initiatives will result in irreversible future financial losses. With natural disasters caused by climate change, eventually the proposed complex on the Irpin floodplain could be flooded. Additionally, peat and organic floodplain soils are not suitable for construction; peat soils can subside 1-2 cm annually. The costs of repairing infrastructure damage and frequent maintenance will be huge.

The Irpin River and its peatlands and floodplains require careful professional assessment, monitoring, and ongoing work over the decades ahead. This complicated task cannot only be managed by national experts, but must absolutely involve international experts from countries where river restoration is a common practice.

Documentary filmmaker Olesya Morhunets and Olga Denyshchyk discuss Irpin River floodplain restoration potential.

Floodplain restoration

Irpin: Snake of peace

Vincent Mundy a Kyiv-based photographer and journalist, launched a discussion in May 2022 in The Guardian about the Irpin River’s fate. He shared his photos and vision for the future of the river with the UWEC team:

I see the Irpin as a giant snake protecting Ukraine from invaders for thousands of years to come and a 3000 km2 peace park of pristine riverine ecosystems unrestricted in flow or volume.

A highly-protected contiguous 162 mile-long wildlife corridor of wetland habitats, with grass and meadowlands surrounded by swamps, marshes and bogs; where water buffalo are as common as beavers and white-tailed eagles soar over flourishing colonies of rare migratory birds enjoying a rich diet of wild grasses, flowers, nuts, fruit, and fish.

In a wide buffer zone people from near and far come closer to the wilderness, for birdwatching, wildlife safaris, or just to rewild the soul. Here an enterprising zone is carefully interwoven with the local ecology. Horticulture and aquaponics will flourish and “the snake of peace” will bring jobs, wealth, and global admiration for the Irpin, for Kyiv, and the nation.

Conservation realism

Valeria Kolodezhna and Oleksiy Vasyliuk, experts at Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, discussed the future of Irpin’s wetland through the lens of harsh environmental realism and a “Why mess with success?” approach.

In their view, flooding the Irpin valley is definitely more beneficial for wildlife, as it will leave the area in a near-natural state and, even better, interfere with plans for large-scale development. The territory requires environmental monitoring, due to an exchange of introduced species between the river and the reservoir, as well as the river’s technogenic pollution.

At first glance, Irpin’s flooding helped to stop the distribution of floodplain land for development or plowing (previously occurring in violation of Ukraine’s Water Code). It is obvious that for at least next year the floodplain will not be developed, because it is currently covered in 2,842 hectares of shallow waters. The environmental consequences of flooding are wider and more ambiguous than they may initially seem.

Flooding is accompanied by pollution and is fraught with disease outbreaks. Some of the flooded and plowed areas were, apparently, treated with organic fertilizers the previous autumn, and those substances are now dissolved in the water. Individual households in the villages of Kozarovychi and Demydiv were partially flooded, construction sites on the Irpin floodplain were flooded (for example, the Khutor Demydivo housing cooperative), and chaotic landfills were flooded. Taken together, these issues constitute enormous environmental risks and threaten to spread infectious diseases.

People in rural areas often drink water from surface (unprotected) aquifers while also dumping waste in the same places. Apparently, not all flooded and submerged households are connected to centralized sewer systems; some houses are simply equipped with cesspools, now flooded. Consequently the Kyiv reservoir is polluted with household waste, and the stagnant nature of the newly formed waters accelerates eutrophication.

Russian forces abandoned many tanks and other military equipment in the Irpin basin, the fuel tanks of which contain remnants of fuel and lubricants. Fortunately for the river, most of the equipment was likely bogged down on approaches to the floodplain, although some oil products and oils still enter the river. When fish ingest or absorb fuels and lubricants, it results in destruction of the tissues in their gills and intestines, mucus secretion, respiratory failure, and metabolism issues. Of course, the use of such water in farming causes serious negative reactions in the human body.

It is important to remove remaining equipment in ways that have minimal consequences for environmental and public health. When water levels drop temporarily at the end of summer, it will be possible to do this with minimal damage to ecosystems. It is also important to organize ongoing water quality monitoring in both the most flooded areas and in wells in nearby villages.

As for fish populations, one should not assume that an increase in the surface area of water bodies has a universally positive effect on ichthyofauna. Restored connections with the Dnipro River and flooding of the tributary’s shallow mouth are promising for the reproduction of fish from the reservoir. So, for example, in Kremenchug reservoir, a similar bay formed at the site of the flooded mouth of the Sula River, becoming Nizhnesulsky National Park – an important site not only for fish spawning, but also as nesting habitat for many water bird species. Another concern is that rheophilic fish species (those that rely on running water) cannot live in a flooded area. In addition, the Irpin River will be more actively colonized by alien (invasive) species originating in the Kyiv reservoir; the Kozarovychi dam previously served as a protective barrier for the river. In turn, the Kyiv reservoir will become vulnerable to invasive species commonly found in the Irpin (sun perch, rotan, etc.).

The discussion about how to deal with flooded lands is more and more relevant today. Landowners and construction companies with plans to build in the river valley will, naturally, be in favor of restoring the status quo and pumping out floodwaters, despite the fact that pumping out such a significant volume is not easy and or cheap. Residents of the flooded village of Demydiv also wish to lower the water level below the level of their properties.

As we know from a public statement on 29 July 2022 by Vladimir Podkurganny, head of the Dymersky community, water began being pumped out in July. But who made this decision and what is the decision’s exact wording? At a minimum, it would help to understand whether pumping will continue only until the residential sector of Demydiv is freed from floodwaters, or is it planned to pump all the water out of the floodplain? Unfortunately, wartime conditions mean that we cannot get full answers to questions of this kind.

But objective reality will likely result in everything remaining as it is.

On the one hand, the flooded area remains an important defensive line, much more powerful than a small river and a reclaimed floodplain. On the other, a flooded floodplain has greater advantages in nature conservation terms. It cannot be plowed and built up; it will naturally transition from vegetable gardens and degraded meadows to ruderal vegetation (the first plants to colonize disturbed lands) in natural shallow-water biotopes. There will be no cause for worry about disturbance factors to bird colonies in these waters.

Thus, in the context of a post-war shortage of resources, maintaining the water body created after the dam was blown up will be the most environmentally friendly and economical way to manage this natural-anthropogenic complex. (For more information, see the UNCG website)

To date, there is no publicly available information regarding any possible government decisions on the fate of the Irpin River valley.

The Ukraine Nature Conservation Group contacted state authorities seeking an answer about plans for the river. Through the Department of Ecology and Natural Resources of the Kyiv Regional State Administration (letter dated 03.08.2022, No. V.2290.2022) it became known that after receiving an appeal, pumping halted, and consideration of the question of flooded territory’s fate was passed to Valerii Zaluzhnyi, commander-in-chief of the Ukraine Armed Forces. Perhaps this indicates that pumping occurred without proper government process and without accounting for Kyiv’s defensive interests.

What conclusions can we draw at this stage?

First, we must acknowledge that the flooding of the Irpin valley is one of the two most significant landscape change events resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. UWEC Work Group has already written about the second incident – the draining of a dammed reservoir on the Oskil River.

Such large-scale topographical changes have attracted the attention of many stakeholders: those seeking to develop the river valley and thus advocate its drainage; residents of Demydiv, who simply want to free their homes from water; the military, who need a flooded valley as an insurmountable water defense line; and conservationists who insist on keeping the Irpin valley flooded and not only returning it to nature, but also guaranteeing that future development will not occur.

Ukrainian government representatives have not (yet) organized any dialogue regarding the river’s future despite many differences regarding the unfolding events. The absence of such a dialogue increases tensions around this issue. There is no publicly accessible information about any official decisions regarding the flooding of the river valley or the opposite, pumping water out of the flooded area.

No solution to this problem will simultaneously satisfy all interested parties. If Irpin valley flooding is allowed to remain, Ukraine will strengthen its defense capability and tangibly succeed in maintaining Irpin’s international conservation status as a member territory of the European Emerald Network. That choice also means that if waters do not recede, dozens of houses in Demydiv will remain flooded unless new dikes are built to protect settlements.

As more official information about Irpin’s fate becomes available at the state level, UWEC Work Group will continue reporting on this topic. We will also be ready to aid in identifying stakeholders for discussions about the future of the Irpin River.

Comments on “Plans to rebuild Ukraine shaped by solutions for Irpin”